The project debt payment plan finally kicked in on my Honda SL125

Within the 700 square foot of space I call my home shop, there is a lot going on. The array of projects in various states of completion is intentional, mainly because it means there is always something for me to do. Plus, if I stumble onto a project that leaves me overwhelmed or suddenly disinterested, I can loosely bolt it back together and shove it in a corner for year and no one but me will be the wiser. That’s generally true, except that last year I let slip to you my Honda SL125 project; the little bike that has been a real drain on my motivation lately.

It all came to a head when I loaned my garage space to a local film crew to shoot a commercial. One member of the crew took a real liking to the SL125 and asked for the number that would make me sell it, to which I confidently replied with the phrase I thought I would never say; “That one’s not for sale, I’m gonna fix that up one day.”

How did I become the person I had sworn not to be? If I am over my head with too many projects and not enough money—I’m close—it makes sense to sell one to keep everything else on track. Instead I went full lizard brain and clutched tighter. It was in that moment that a realization washed over me: Last time I wrote about this bike it included a comparison between it and my student loans, and as with my loans for the six months after graduation, I had been granted a deferment on payment. Eventually though, the time comes to pay up.

That first payment is the one that hits the hardest, so I took to crossing off the largest line item on the SL125 to-do list: getting it running again. It’s tricky first step, because Honda designed the SL to run off a battery, with a six-volt direct current coil and lighting system—just a few of the items that I did not like about the bike. The plan I laid out was to remove the battery to clean up the overall appearance and create more of a street-tracker look. I started the process last winter when I built my own wiring harness, then I got bogged down in the minutia of how a motorcycle stator works and how I could adapt it to do what I wanted it to.

Fortunately, I was not alone in my desire to remove the battery and clean up the wiring on the SL125. Multiple folks with more experience shared their methods with me for accomplishing the task, and all I had to do was follow their steps. It wasn’t a difficult process, but I’d been putting it off.

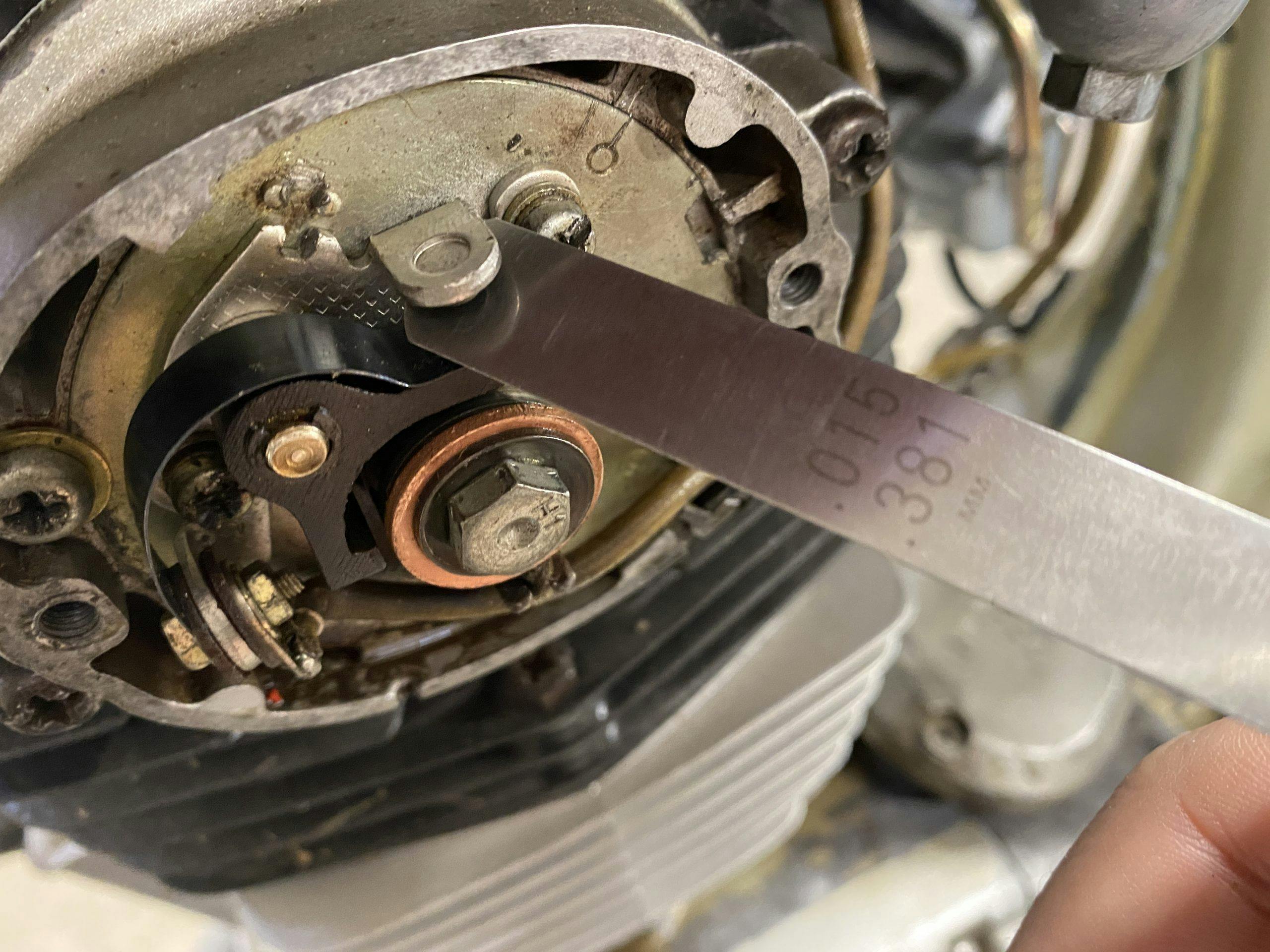

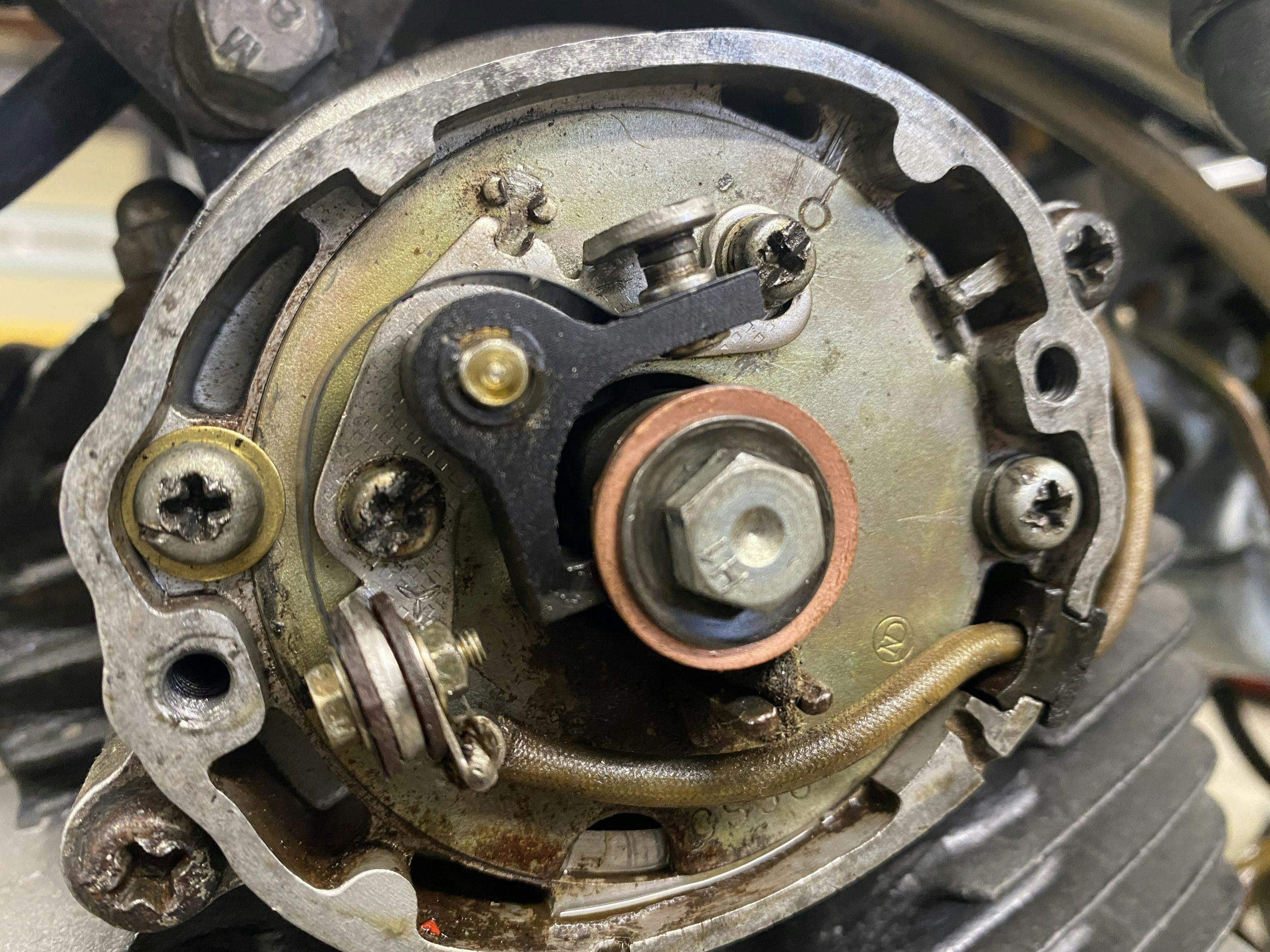

Until this weekend, that is. I finally dug in and started by setting the points to the proper 15-thousandths gap, confirmed the timing was correct by referencing the “F” mark on the flywheel to when the points opened, then removed the centrifugal advance and locked the timing at full advance using a copper washer behind the bolt that holds the points cam in place. Then I removed the flywheel using the rear axles as a puller, removed the woodruff key that aligned the crankshaft and flywheel, and reinstalled the flywheel so that the “F” timing mark still denoted when the points opened. The precision fit of the crankshaft to flywheel taper, and the 14mm bolt that holds it together will suffice to keep things from slipping.

Next came replacing the six-volt DC ignition coil for a six-volt AC unit (Honda part number 30500-950-405 if you are playing along at home) to match the output of the stat0r. I then connected my wiring harness and fuel lines, crossing my fingers it would start. It sputtered and puttered, but a smooth start and idle escaped me. Diagnostics showed a good hot spark from the plug, though, so I knew exactly where to look.

This bike has some history to it, but at some point it was hobbled together as a yard or field bike for someone’s kid and, thus, little money was invested to get it running. I know this because the Sheng-Wey carburetor bolted to the intake manifold is a cheap piece of garbage. It’s a knock-off of the proper Keihin carb that would have been what Honda fit to the bike when new, and as a result suffers all the problems common with knock-off carbs. Luckily, it is a very simple part with only two circuits, both of which I found clogged. Compressed air and a little bit of cleaning took care of that, and I also took the extra step of flushing the fuel tank to hopefully stop more junk from making its way into those small passageways.

Three kicks of the starter later, the bike easily puttered to life and settled into a smooth idle. The person I bought the bike from claimed he put on a new piston and cylinder right before I bought it, and given the way this bike runs I don’t think he was lying.

There is still a whole bunch of work to do before this Honda could be called finished, and like any good project it won’t ever be completely done, but I’ve made my first big payment to chip away at my SL125 labor debt, and it feels darn good. Motivating, almost. Now where did I put that to-do list?