Droptop Supreme: The inside story of Oldsmobile’s last convertible

It was February, 1988, and Georgia’s Doraville Assembly was filled with gleaming new Oldsmobile Cutlass Supremes. Five years and $7B had been spent on the new front-drive Cutlass and its W-body (at first “GM10”) siblings, the Buick Regal and Pontiac Grand Prix. These were boldly styled, aerodynamic, high-tech cruise missiles aimed at Ford Thunderbirds and Honda Preludes alike. Unfortunately, the car market was more interested in Mercury Sables. The early W cars were a costly swing-and-miss.

First impressions really count in the car business. They looked awesome, but the early Ws never met their over-optimistic sales projections. The sporty, high-tech image was undermined by 1988 models landing only with the 130-hp 2.8-liter V-6, an engine shared with the Chevy Cavalier.

In March of 1989, Doraville was idled for a month because of overstocked dealers. GM was also losing $1800 on every W it built. GM’s gleaming, robot-filled factories—each dedicated to a single model—couldn’t flex with demand and operated way below capacity, a symbol of Roger Smith–era dysfunction.

There was one W-body everybody seemed to love: the Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme Convertible. Based on a small run of convertibles built for the 1988 Indy 500 pace car program, the full production version looked great and demand outstripped supply for much of its 1990–95 run. The droptop Supreme ended up being Olds’ final ragtop, and 35 years later, both the coupe and convertible have come into their own as classics. The styling still stands out.

As a car-obsessed kid, I loved the wild design of the Cutlass coupe and convertible. But I always wondered how such a radical departure from the previous Cutlasses happened. How did that convertible get made? To get the answers to those questions, I sat down (separately) with Ed Welburn, GM’s VP of global design from 2005 to 2016, and David Draper, former CEO of Cars & Concepts (C&C), who engineered and converted the cars.

In the mid-1980s, Welburn was an Oldsmobile studio staffer working under design leads John Perkins and, later, David North. While Welburn was helping shape the Cutlass and the streamlined Aerotech, Draper was designing convertibles for Chrysler and Ford as well as projects for Olds that Welburn also worked on, like the 1983 Hurst/Olds and the 1985 Cutlass Calais pace car, both projects Welburn also worked on.

“It happened that C&C was in Brighton [Michigan], right between Oldsmobile in Lansing and GM’s tech center in Warren,” Welburn said. “That made them an easy partner but they also put real quality into what they did. I recall many drives to Brighton.”

The Aero Cutlass

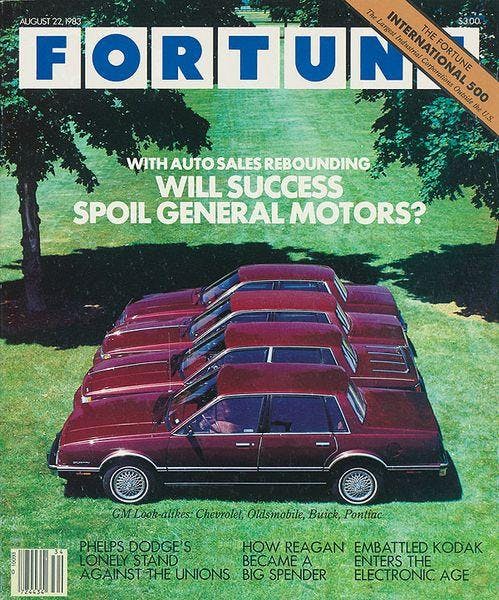

Work began on the W-body in 1983–84, when the “aero look” was king. Welburn credits that aesthetic to the influence of the Audi 5000 and Ford Sierra. “GM had also done concepts like that, but we’d never put anything like them into production.” As it turned out, that would soon change—possibly because CEO Roger Smith had been skewered in Fortune magazine in 1983 for the company’s “cookie cutter” cars and seeming lack of interest in design. The magazine parked four burgundy A-body sedans next to each other to hammer home the point.

“I’d worked on the previous three Cutlasses and they were all big sellers,” Welburn said, “but the edict, from Smith directly, was that change was needed. In the studio, I did a whole lot of sketches, evolutionary and revolutionary, but when the time came to choose, the direction from the top was definitely ‘revolutionary.’”

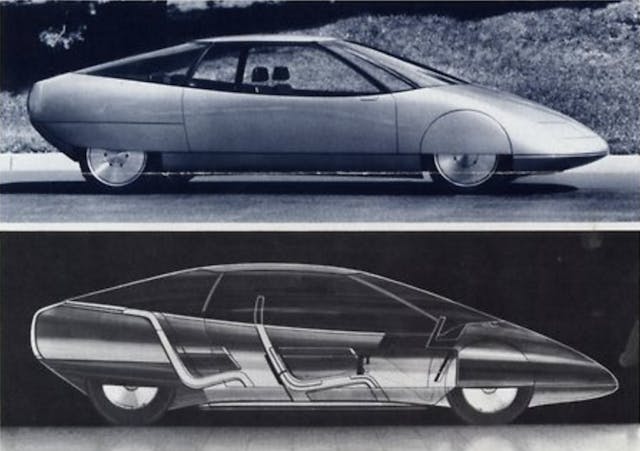

Smith had a specific example in mind: the Aero 2000 concept car created for GM’s exhibit at Disney World’s Epcot Center. “It was a very aerodynamic, sleek-looking car, but also very small because it had to fit in the exhibit. It had a glass-to-glass roof with no conventional sail panel, which was part of our inspiration,” explained Welburn. Aside from its electroluminescent dashboard, the interior was less radical and more of an evolution of the previous car.

“As designers, we were all excited to work on something that cutting edge. But the whole time we were working on it, market research kept saying that this wasn’t exactly the right car for the moment.” It was, however, what leadership wanted.

Part of the issue, Welburn said, is that the market was trending away from coupes and towards sports sedans. “The Taurus really fit that bill, and we were only working on coupes.” There was a Chevy sedan in the pipeline but the other sedans didn’t arrive for two years after the coupes because they were added very late in the game. In 1988 and 1989, four-door buyers would be shown to the Cutlass Ciera, one of the Fortune cover cars.

Sure enough, Once the Cutlass arrived, it didn’t meet sales aspirations. “We got really good press and the car looked really distinctive,” but as predicted by the researchers, the lineup only having coupes to sell didn’t help the launch. Nor did the memorable but incoherent “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile” ad campaign promoting the new Supreme, which demeaned existing Olds customers while simultaneously failing to win new ones.

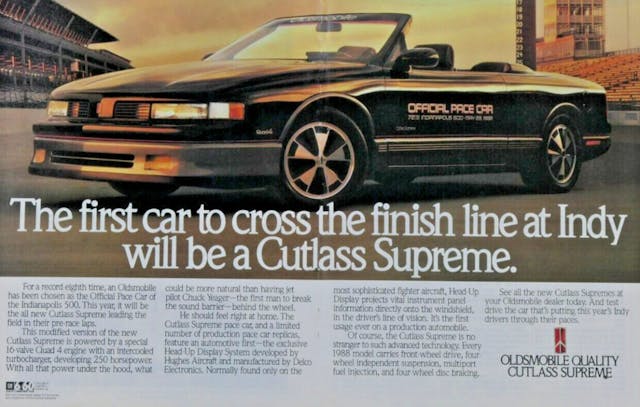

The pace cars

The Indy pace cars of 1988 were part of that initial marketing push, but they also had another purpose. In talking with Welburn about my own recollections of the cars, I mention my favorite NASCAR driver, Harry Gant, who famously piloted a Cutlass to four straight wins in September 1991.

“It’s funny that you mention Gant,” Welburn said. “Towards the end of the design program, we created a special fascia meant for drivers like Gant and A.J. Foyt in NASCAR, Paul Newman, and Paul Gentilozzi in IMSA, and Warren Johnson in NHRA. The car was very aerodynamic for that time, but for racing we knew it needed more of an edge, so we went into the wind tunnel and tested out an altered version of the front fascia. We homologated it by building the pace cars.”

Oldsmobile turned to Cars & Concepts to build its planned 200 pace-car coupes and 50 convertibles, including the three race-use vehicles. Co-founded in 1976 by Draper, a former White Truck engineer, and a veteran of the original Hurst/Olds programs, Dick Chrysler, one of the company’s first jobs was the modifications on the 1976 Hurst/Olds. “We often worked with [Oldsmobile chief engineer] Ted Lucas back then,” Draper said. That first project led to many more.

The coupes were just a paint and trim job, while the race-day cars were repurposed development mules powered by heavily massaged Quad-4 engines and no provision for a top or exterior door handles, though they did have a super-cool Hughes Electronics head-up display. But Olds also wanted working convertibles for dealers.

A gaggle of droptops were laboriously built and later distributed to dealerships but, clarified Draper, “It was impossible to build them properly in low volume and in that time frame.” GM quickly bought most of the cars back, ostensibly because of a “certification issue,” but the exact details are unclear. Several dealers refused to part with the cars, and thus, a small number survived. Draper isn’t sure if the full run of 50 was actually finished. “I was, after all, the CEO, and focused on bigger projects.”

Though rough compared to what came later, these droptops made a big impression. “The pace car got people excited about a convertible, and that’s what really got the ball rolling [for production],” said Welburn.

The challenge of convertible conversions

At first glance, the Cutlass’ glassy roof looks like an easy starting point for a convertible adaptation … until you see the door handle on the B-pillar. “If you want to move that handle you have to retool the whole door and everything in it,” said Draper. It would have been a huge expense. “Our solution was to design a concept that retained all of the interior door mechanism and used a hoop. It was not a roll bar but a design element.”

Nor was the approach inspired by Volkswagen and the Cabriolet, he confirmed. “Some people who loved it and some people hated it.” The hoop was part of the car from the start, even on the pace car units.

The convertible’s engineering was a 50-50 collaboration between C&C and Lucas’ engineering team at Oldsmobile. The most important part of the production conversion development, Draper said, “was convincing Oldsmobile to do all the body changes in the body in white,” the phase at which all the structural elements of the unpainted car are complete. Starting the conversion later would have also driven the price too high.

All this meant a very involved process at Doraville.

C&C pulled bare-metal coupes off the line and trucked them to a parallel shop. “There, we’d remove all the parts that weren’t necessary and add the parts that were, including rebuilding the door and strengthening the floor and rocker panels, the whole works.” The bodies were then trucked back to Doraville and inserted on the line in their original slot. “So their line kept running and so did ours.” After trimming, the cars returned to C&C’s shop for the rear seats and top.

“The system worked really well, and I think we built it to a standard we couldn’t have any other way short of building the whole body ourselves. We might’ve changed the door if we’d done that, but the car would have been unsalably expensive,” said Draper.

As it was, the production convertible was about $4500 pricier than the coupe. The hoop design was later integrated into the limited-production Chevy Beretta convertible, “which was also a pace car and also had those door handles,” Draper laughed. Logistical and crash-test hurdles prevented that one from getting built in volume.

Welburn was also pleased with how the car translated into a droptop: “I remember many afternoons working with C&C on that project making sure everything looked right. I’m not an engineer, but visually it was a good result.

“One of the things I think is nicest about this car is that it’s a convertible with a meaningful back seat, which you rarely see now. I have a friend in Italy who has one of these Cutlass convertibles and he loves the car both for the style and the practicality. Plus, the top is fast. Sixteen seconds, I think?”

Mechanically, the cars were identical to the standard Cutlass coupe but 370 pounds heavier. They delivered the same competent and smooth but relaxed driving experience, although in 1990 and 1991 Oldsmobile started to add more punch to the coupe. The 140-hp 3.1-liter LHO V-6 was added for 1989, then 1990 brought the Quad-4 (160 or 180 hp), and in 1991 the 200-hp 3.4-liter LQ1 V-6 was made optional. Convertibles came only with the 3.1 or, after 1993, the 3.4.

The collector convertible

The Cutlass’s big wheelbase and usable back seat made it a rarity among convertibles in the early 1990s—and a hit with upper-middle-class buyers—with demand outstripping supply for much of the car’s run. In the summer of 1992, Olds marketing manager Lisa Crumley called the car “a real success story for Oldsmobile,” and sales soared from 1340 cars in 1991 to 8638 in 1994. Unfortunately, the story ended soon after.

Part of the problem was that GM had originally planned to build 250,000 Cutlasses a year at Doraville; it never managed more than 116,000. After years of running under capacity, production was moved to Fairfax, Kansas, in 1995, where the Pontiac Grand Prix was built, and the plant in Doraville was retooled for the GMT200-generation minivans. Moving convertible production was unfeasibly expensive, so it ended. Nobody could have known that it would be Oldsmobile’s last ragtop, but that anticlimactic end disguises the fact that collectors liked it from the start.

“We actually had two of them for a while,” says Ed Konsmo, owner of the silver ’91 featured here. An Olds collector since the 1980s, he started with a ’65 Cutlass convertible and currently also owns a 1950 98 Futuramic sedan, but the W-car’s cool styling and practicality were a big draw. “We bought our first one, a white ’92, in 2010, but later on a friend in the Olds club who owned this ’91 passed away, so my wife and I bought it.”

In the first two years, Cutlass Convertibles were not easy to get, and the original owner special ordered it and waited months for delivery, but rarely used it. It may be one of the nicest, most original examples in the world. “It’s one of only three in this color combo, and it had 17,000 miles on it when we got it three years ago. It’s a sunny day, date night kind of car.” Everything on the car is as it left Doraville and 100 percent original. Aside from the tires and a horn that doesn’t honk, it all operates like a new car.

Konsmo and the car got a warm reception at the 2022 Oldsmobile Nationals in Tennessee, but it draws lots of attention even at more casual events, taking “raddest in show” at the 2023 Radwood PNW event. He was surprised at the interest in the car from younger people, and also happy to learn that these Cutlasses and other post-1980 GM front-drivers are inspiring a thriving online fandom.

His message to fans who want to preserve this era of Olds history? “Get involved with clubs, they need you!”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

This version of the Cutlass is one of the best front ends I think ever designed into a car. In particular the wonderful thing headlights.

Oldsmobile gets a bad rap for their 1980s marketing, but the fact that you remember it proves it worked. How did it alienate buyers? You got out of it what it meant to you, whether it was moving away from v8 gas guzzlers, or tail fins and vacuum tubes. Unfortunately GM used that “generation” as test subjects for its Quad 4 and Northstar-powered Auroras. The Alero was a rental car queen with cheap plastic, the Sierra and Calais were indistinguishable from a Saturn and the Cutlass became a rebadged Malibu.

It’s as if they intentionally killed the brand. No amount of marketing could overcome that.