Yes, it really was your father’s Oldsmobile

In 1988, GM’s Oldsmobile brand introduced what it described as a new generation of cars under the tagline “This Is Not Your Father’s Oldsmobile.” The commercials featured celebrities like William Shatner and Ringo Starr paired with their adult children.

Oldsmobile was then possessed of a relatively old customer base. Although the brand’s storied history contained some notable performance cars, the division’s public image featured stodgy, boring vehicles and customers middle-aged or older. While the “not your father’s” line caught the public’s ear and continues to resonate in meme and cliché, it didn’t help revive the brand. In fact, that ad campaign is often seen as one of advertising’s classic failures, turning off Oldsmobile’s older customers without attracting the younger ones so badly wanted by the marque.

In my case, it really was my father’s Oldsmobile. In 1964, my father was 44, firmly in middle age. A couple of years later, he bought a fire-engine-red 1966 Delta 88. That car was his second Olds, the first being a 1958 model he acquired from his father-in-law. This ownership chain made the car not just my father’s Oldsmobile, but my grandfather’s Oldsmobile. When the latter parted with the ’58, he replaced it with a brand-new 1961 Olds 98 four-door.

Modern critics blame It’s Not Your Father’s Oldsmobile for the brand’s demise. Statistics, however, indicate that, although the slogan didn’t turn Oldsmobile’s fortunes, the brand was already in decline when that campaign was launched. Oldsmobile, founded in 1897 and dissolved in 2004, saw its annual sales peak in 1984, at just over 1.2 million vehicles. By 1988, when the slogan was introduced, production had already dropped by more than a third, to 764,134.

The late ’80s wasn’t the first time that Oldsmobile’s marketers missed the mark with the youth market. A while back, I found evidence of that fact in a pile of vinyl LPs that someone gave to me rather than throw out. My music collection includes hundreds of LPs, so I still have a turntable.

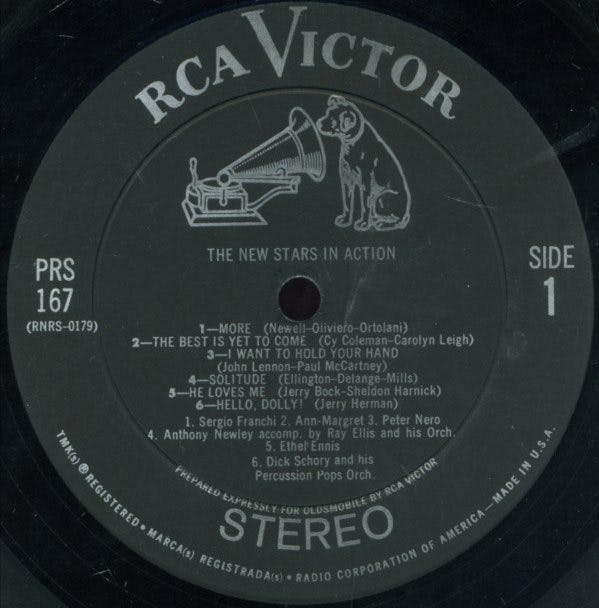

Don’t believe the hipsters; not all “vinyl” is collectible. Plenty of old “record collections” include mass-market recordings like freebie promotional discs. RCA even had a special distribution channel and secondary label for promotional records. One of the LPs I was gifted is just such an RCA promo release, from 1964: Oldsmobile Spotlights the New Stars in Action (RCA Victor PRS 167). The only thing automotive about the album is its cover art, which features a whitewall tire and an Oldsmobile hubcap.

From the beginning of the industry, automotive marketers have generally had their fingers on the pulse of the public been quick to recognize societal changes. What was changing in 1964? Music, for one thing. In February of 1964, the Beatles first appeared on NBC’s influential and widely watched Ed Sullivan variety show, and The Rolling Stones would be on the same show that fall. Rhythm and blues and rock and roll were beginning to dominate the pop charts, and electric-guitar manufacturers could not keep up with demand.

Oldsmobile had its own association with those musical genres. The song generally regarded as kicking off the rock ‘n roll era was Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88,” a 1951 pop tune that that crossed over from the R&B charts and happened to be about an Oldsmobile.

One would think that, by 1964, the suits managing the brand might have been at least a little bit hip to new music. What did Oldsmobile and RCA pick to represent 1964’s “new stars in action?” This list:

Sergio Franchi: “More”

Ann-Margret: “The Best is Yet To Come”

Peter Nero: “I Want To Hold Your Hand”

Anthony Newley: “Solitude”

Ethel Ennis – He Loves Me

Dick Schory and His Percussion Pops Orchestra: “Hello Dolly”

Womenfolk: “Morning Dew”

John Gary: “Take Me In Your Arms”

Gale Garnett: “Prism Song”

Ed Ames: “But Beautiful”

Ketty Lester: “We’ve Come A Long Way”

Glenn Yarbrough: “San Francisco Bay Blues”

Viewed as anything other than a youth effort, the album doesn’t have a thing wrong with it. Feel free to give a listen and judge for yourself. The performances are professional and entertaining, but if GM thought these “new stars” would produce any action with young-adult consumers, they were mistaken. Nothing on the LP really reflects the massive changes then taking place in the world of music. I assume the songs were suggested by RCA, to promote certain house artists, and then approved by GM, which surely didn’t want to offend anyone with loud, long-haired music. The people involved with the project obviously knew of the Beatles—the album contains a cover version of “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” played by pianist Peter Nero and his orchestra—but the arrangement of the British band’s song is as far from the rocking original as you can get. (Nero based his neo-classical arrangement here on Percy Grainger’s pastoral “Country Garden,” which evokes thoughts of Allan Sherman’s parody, “Here’s To The Crabgrass,” not youth culture.)

With the exception of the two “folk songs” here and Glenn Yarbrough’s version of “San Francisco Bay Blues,” every track features a big-band arrangement with strings and horns. I suppose the two folk tunes were a nod to youth. The song “Morning Dew” was contributed by Womanfolk, an all-female folk band that, according to the liner notes, was “cresting the new wave of folk music from West Coast to East.” Gale Garnett is included here with “Prism Song,” from her album My Kind of Folk Songs. This is even more missing of the mark—although folk music had been quite popular with youth for some time, by 1964, the folk craze was dying, not cresting. One year later, at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, folk landmark Bob Dylan would famously “go electric,” prompting the country to turn away from the genre.

Don’t get me wrong: Many of the performers on the album were genuine stars in 1964, and they all had releases on RCA, one of the biggest major record labels that has ever been. Ann Margret, then 23, was probably the youngest performer on the album, and 23 is by no means old. For that matter, in 1964 as now, the radio held plenty of middle-of-the-road pop music, even on youth-oriented Top 40 stations. Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Hello Dolly” was a huge hit that year, breaking the Beatles’ string of three number-one hits in a row. Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and other more adult-oriented performers regularly charted in the mid-’60s, and the Beatles even covered show tunes like “Till There Was You,” from Meredith Willson’s hit Broadway musical The Music Man.

Recognizing that hindsight is 20:20, and that the past is a foreign country where they they do things differently, you can’t really fault the folks at Oldsmobile back then for using popular culture to sell cars. From a modern perspective, it looks as if RCA—or at least Oldsmobile—didn’t recognize a changing culture, but that may not necessarily be the case. The carmaker may have tried to change its image in the late ’80s, but as we can see from the brand’s promotional efforts, that image was well-set two decades earlier. The music on Oldsmobile Spotlights the New Stars in Action probably reflects the tastes of Olds customers in 1964 with some accuracy. Oldsmobile may have been trying to look au courant with an album like this, but they weren’t trying to sell cars to the youth market, at least then. The people running the brand knew what kind of vehicles they made and who their customers were.

If you want to add a copy of this album to your collection, fear not: Although the album’s cover art features the words “Collector’s Limited Edition,” it’s readily available on eBay and used-record sites.