A family affair: Driving the Allard JR continuation car

As of now, you can buy a new Allard JR. Having driven it, I can report that if you did so, you would enjoy it a lot. Most likely you would race it, for that is its purpose, and it has FIA approval to confirm its authenticity as a continuation of a short line of such cars built in the 1950s. Sounds great, you think. But, actually, what on earth is it?

Allard is a name from a distant past of British sports cars, forgotten by most who might once have been aware of it, unknown to everyone else. To jog any memories you might have, Allard’s best-known machine was the J2 of the late 1940s and early 1950s, with a Cadillac V-8, a pre-war look, and plenty of pace. Most went to the U.S., many were raced.

Then there was the Allard P1, a bulbous two-door whose long bonnet covered a Ford V-8. It remains the only car to win the Monte Carlo rally when driven by its creator, a feat achieved by company founder Sydney Allard in 1952. Several other sporting cars on this generously-powered theme continued until 1958, at which point the more modern-looking Palm Beach sports car, usually powered by either a Ford Zephyr or a Jaguar XK straight-six, ended production at Allard’s works in Clapham. After that, Allard was mostly about selling Shorrock superchargers and setting speed records in some small but very effective dragsters driven by Sydney’s son Alan.

From the European perspective, though, there was another major Allard moment in 1953. Sydney led that year’s Le Mans 24 Hours from the start, albeit briefly, in his new JR sports car, outfoxing the might of Jaguar and Ferrari and bellowing into history. This JR, one of two works entries, lasted until lap four and either the demise of the differential or a severed brake pipe caused by the collapse of the rear suspension. History offers us a choice of explanations, but either way it meant that co-driver Philip Parker didn’t get to race.

That car had chassis number JR3402, making it the second of seven JRs to be built in the 1950s. The second works car, numbered JR3403 and co-driven by Zora Arkus-Duntov who had designed the original Chevrolet Corvette, lasted 568 laps before its Cadillac V-8 went bang on the Mulsanne Straight. Other JRs later raced with some success in the U.S.

There’s some history to celebrate, then. And in these modern times, present-day owners of famous sporting brands see money to be made in ‘continuation’ versions of past competition, or otherwise significant, cars that helped forge the brands’ reputations. Jaguar has given us new C-Types, D-Types and Lightweight E-Types. Aston Martin has built new DB4 GTs and is doing the same with Bond-equipped DB5s. Bentley is making new vintage Blowers, and racing-car manufacturer Lister is recreating Knobblies. Some of the Ford GT40s racing today are new ‘official’, though third-party, facsimiles of original cars that stay safely tucked away.

And now there’s a new Allard JR. Just one, so far, but there could be more. This continuation project, though, is different in two key ways. First, it has been built by Sydney Allard’s son and grandson, Alan and Lloyd. Mainly the latter, an expert engineer whose Gloucester workshop is normally immersed in turbocharger reconditioning and aluminum fabrication, but the two of them—along with Lloyd’s brother, Gavin—have now resurrected the family sports- and racing-car firm. No other continuation car has such continuity with the people behind the original.

Second, no scanning, digitization, reverse-engineering or any other post-millennial trickery has been used here. Instead, Lloyd fabricated the hefty tubular steel chassis from the original drawings—120 in all—by Dudley Hume, Allard’s engineer at the time. Hume, who died in May 2019 at the age of 96, lived long enough to see the start of the new project. He even re-drew some of the faded lines on the drawings.

The curvaceous body’s provenance is equally authentic. Hume created a wooden body buck over which the original JRs’ aluminum panels were formed, and that self-same buck—returned from a stay in the U.S. where it helped in the restoration of JR3405—has helped Historic Metalworks of Lymington, Hampshire to create the panel work of this new JR, allotted chassis number JR3408.

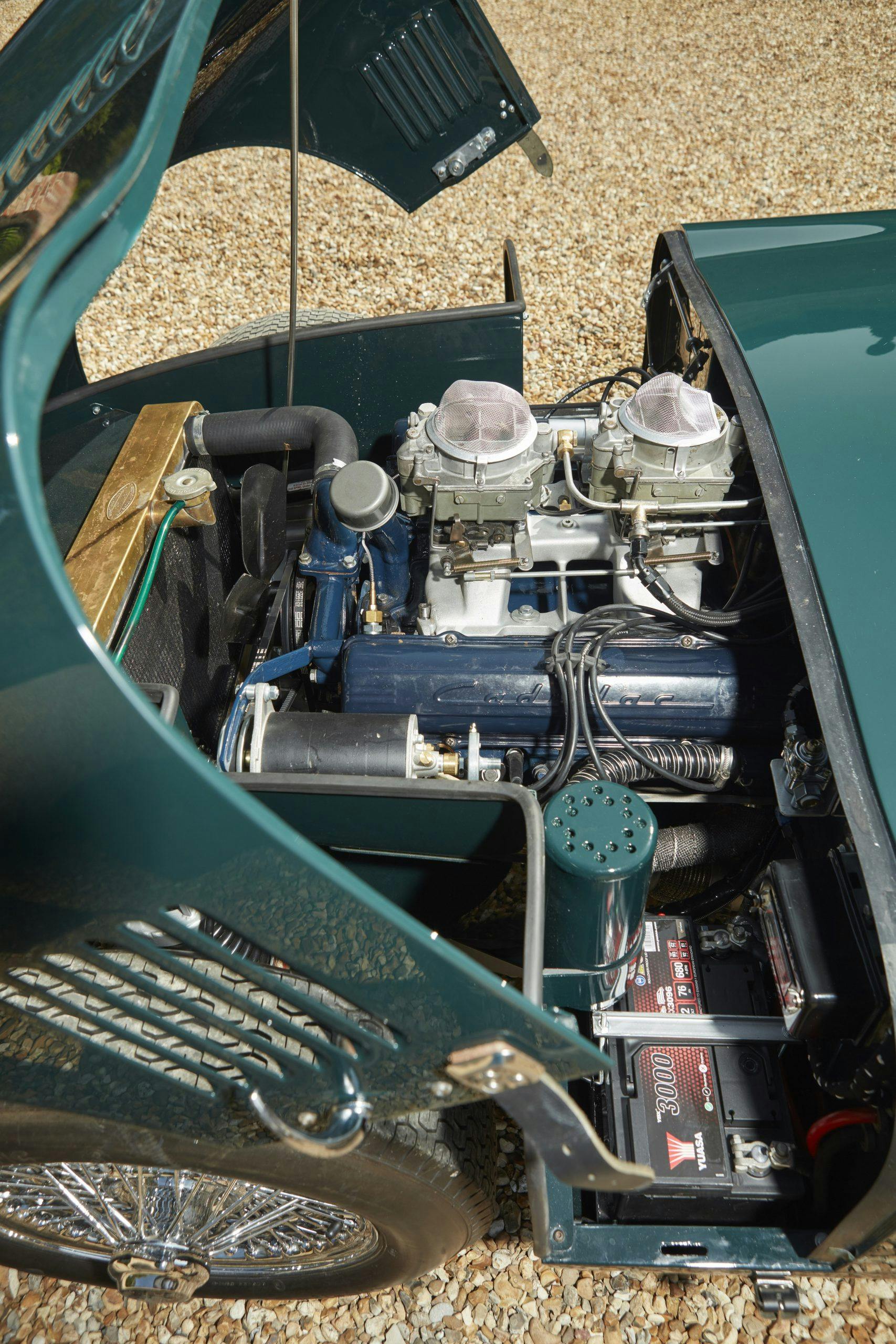

As far as possible, 3408 replicates Sydney Allard’s Le Mans machine, 3402. That means it has a 5416-cc engine delivering around 295 hp. That significant increase over the original Cadillac output is achieved through higher compression, two four-barrel Carter carburetors, and a pair of free-flowing three-branch exhaust manifolds leading to a trio of exit pipes under each sill. Three-branch, on a V-8? That’s because each bank’s two middle exhaust ports are Siamesed.

One departure from originality is the gearbox. A tough three-speeder was the period fitment, with huge gaps between the ratios given the 145mph clocked by Sydney at Le Mans, calling for a very plump torque curve from the engine. That the useful rev-limit was (and is) just 4800 rpm emphasizes the point. Lloyd, however, has opted for a four-speed Borg-Warner T10 unit, although he has retained a period-style, albeit new, Halibrand differential with easily-accessed drop gears to allow rapid ratio-changes to suit different tracks.

I meet the Allard, and the father and son Allards, at an airfield test venue just days after its completion. There’s still some fettling to do; yesterday, the day the photographs you see here were taken, Lloyd noticed a driveline vibration. So, as soon as the JR is unloaded, he’s taking off the rear wheels and repositioning the driveshafts on their splines relative to the universal joints. It’s a chance to see, close up, the design of the rear suspension—a de Dion axle system with triangulated upper and lower locating frames for the cross-tube—and the skill and neatness that have gone into its fabrication.

With that job done, Lloyd fires up the engine. It came from a U.S. Allard enthusiast who had built it for the K2 model he was restoring before plans changed. Plenty of the JR’s other parts are also Allard originals; only if something just could not be found did Lloyd use a modern reproduction, or fabricate the part from scratch.

The engine splutters and blusters, occasional flames erupting under the carburetors’ mesh filters before being sucked back into the throats, and then it settles to a menacing burble. Silencers save our ears from lasting damage, and as Lloyd sets off on a quick shakedown run the soundscape is dominated by a yet louder sound from an unexpected source.

It’s that Halibrand differential’s straight-cut drop gears, their penetrating whine suggestive of a distant angle-grinder. That’s how they are meant to be, apparently, and on his return Lloyd declares that he’s happy. Which means it’s my turn.

Lloyd’s run was an opportunity to see how the JR looks on the move. Under the skin it’s not much different from a J2, but the full-width body, with shades of C-Type Jaguar along the flanks and around the tail, marks the JR as a machine from the next era. There’s a hint of Americana up front, though, a toothy grille flanked by low, protuberant headlights. If a Jaguar and a Corvette got married, this might be the result.

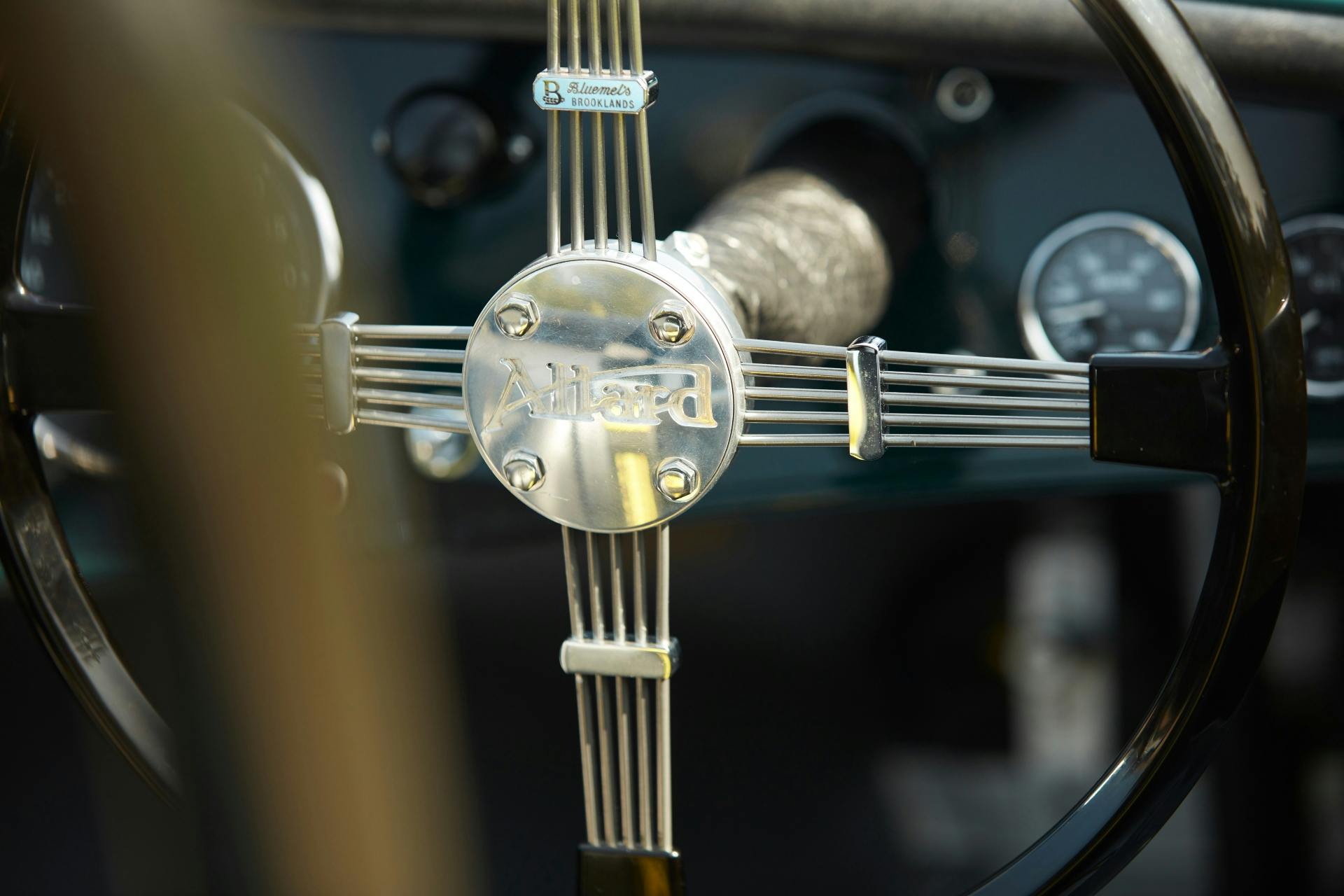

Now for a different view of the JR. I open the featherweight door, fall into the seat’s embrace and hold a very pre-war-looking, four-spoke steering wheel. A Perspex half-width aero windscreen is ahead, big chrome-rimmed dials are to my left, hefty pedals—floor-hinged for clutch and brakes, organ-type for the accelerator—under my feet. It’s all perfect; the love and workmanship that have gone into this eighth JR are breathtaking.

The engine fires instantly and I’m off, exhausts blustering, diff howling, suspension chopping a bit, steering wandering a bit more. This is not a car for ambling in; the steering is impossibly heavy for maneuvering and the turning circle is that of a Routemaster bus, but after some gentle runs to get the feel of the JR’s character I get the all-clear for a rush up the runway.

As power builds, as bluster turns to bellow, it all starts to come together. It’s immediately clear that this engine never “comes on cam” or reveals hidden heights of high-speed urge; once the eight throttles are opened there’s a gurgling torrent of torque right through that modest rev range, easily enough to bridge the wide gaps between the four-speed gearbox’s ratios, and no doubt to have bridged the original three-speeder’s inter-ratio chasms.

The ride is smoothing out and that wandering is lessening. It’s most likely caused by a combination of the old-fashioned Marles steering box and the somewhat impure swing-axle front suspension, evolved from a conversion once popular on old upright Fords which involved sawing the front beam axle in half, mounting the cut ends on a central pivot and triangulating the result with an extra arm. It causes the front track to change constantly over bumps and undulations, but on smooth roads it’s fine. Also fine are the brakes, proving that hefty drums can work well especially when formed from finned, iron-lined aluminum.

A quick squirt of tail-loosening torque as I turn at the runway’s end and the JR is pointed back down the runway for another blast back to base. There’s a slight misfire under maximum acceleration, which Lloyd reckons is a lack of fuel flow and easily fixed, but otherwise the brand-new JR is working very nicely indeed. It’s every bit as genuine an Allard as its seven predecessors, just newer. And if you fancy racing it, it’s for sale at a price far below what you would pay for a historic Jaguar or Ferrari rival—or indeed a remake of one.

The Allards suggest somewhere north of £200,000 ($273,500) for this example, while the price of any commissioned car would be dependent on the client’s chosen specification, but presumably not too far removed from that figure.

That makes it amazingly good value, especially when you consider that, uniquely, it comes straight from a family’s own historic connections. It has been built as much for love as for money, and is perhaps the most authentic of continuation cars. You might feel slightly cheated at seeing a continuation Jaguar or Aston Martin or Ford GT40 racing among real historics, perhaps gaining an unfair advantage through their non-period, computer-recreated perfection, but the new JR has a stronger claim to being the real deal. It’s somehow a more legitimate continuation, imbued with credible soul. That’s something impossible to quantify, never mind build a business case around, but it matters.

Once JR3408 is sold, Lloyd and Alan can finance the building of JR3409. Then, maybe, JR3410 and beyond. Interested? Pick up the phone and speak with the Allard family.

Allard JR Continuation specifications

Price: £200,000-plus, depending on specification ($273,500)

Engine: 5.4-liter V-8

Power: 295 hp

Torque: 380 lb ft

Gearbox: 4-speed, RWD

Curb weight: 1000 kg (est.); 2204 lb (est.)

0-60 mph: 6.0 sec (est.)

Top speed: 145 mph (depending on gearing)

Allard: A once-proud marque resuscitated

Sydney Allard, whose pre-war, Ford-based specials had much motor sport success, set up the original Allard Motor Company in 1945, based in Clapham, south London. His new cars, mostly V-8-powered, continued with a version of Leslie Ballamy’s swing-axle front suspension, one of several ways in which the cars, while undeniably rapid and much liked by the competition fraternity, became ever more dated compared with rivals.

An Allard Safari estate car with “woody”construction, and a relatively modern-looking Palm Beach sports car, weren’t enough to bring in the profits. By the late 1950s the Ford dealer next door, which Sydney also owned, was using some of Allard’s workshop space. That dealership was called Adlard Motors and used a logo near-identical to Allard’s, but the name was purely a coincidence: Sydney’s father, Robert, had bought the original dealership building from a roofing company called Robert Adlard.

In 1958, Allard ceased making cars. From that point it focused on marketing, distributing and ultimately manufacturing Shorrock superchargers, and making the Golde sunroof. A brief return to complete cars came with the Allardette, a Ford 105E Anglia tuned with a supercharger. Sydney and Alan entered one each in the 1963 Monte Carlo rally, finishing first and second in class respectively. Allard also built small, supercharged dragsters, campaigned by Alan and available for sale, but in 1966 the Clapham factory burnt down and that was more or less that.

The Allard name briefly reappeared on three retrimmed Lexus LS400s, but the project quickly died. Lloyd, intrigued, tracked one down on eBay a few years ago. The name found itself associated with various enterprises not necessarily condoned by the Allard family, but by 2012 the disputes were straightened out, the family had regained control of their name and in that year a new company, Allard Sports Cars, was formed.

It makes some new Allard spares, and in 2014 Lloyd began building the chassis that is now JR3408. He and Alan found the original Palm Beach Mk2 motor show car and restored it, and they have built a replica Allardette. Covid has put things on hold for a while, but in the future they would like to build the new, modern sports car that they are designing. And, of course, more JRs.