Remembering Marvin Tamaroff, innovative car dealer and mascot-collector extraordinaire

Marvin M. Tamaroff passed away this summer, in early July, at the age of 95. The auto industry will remember him as a pioneering dealer who helped shape the way cars and trucks are sold. Car enthusiasts, however, will remember him as the automotive world’s preeminent collector of car mascots and hood ornaments.

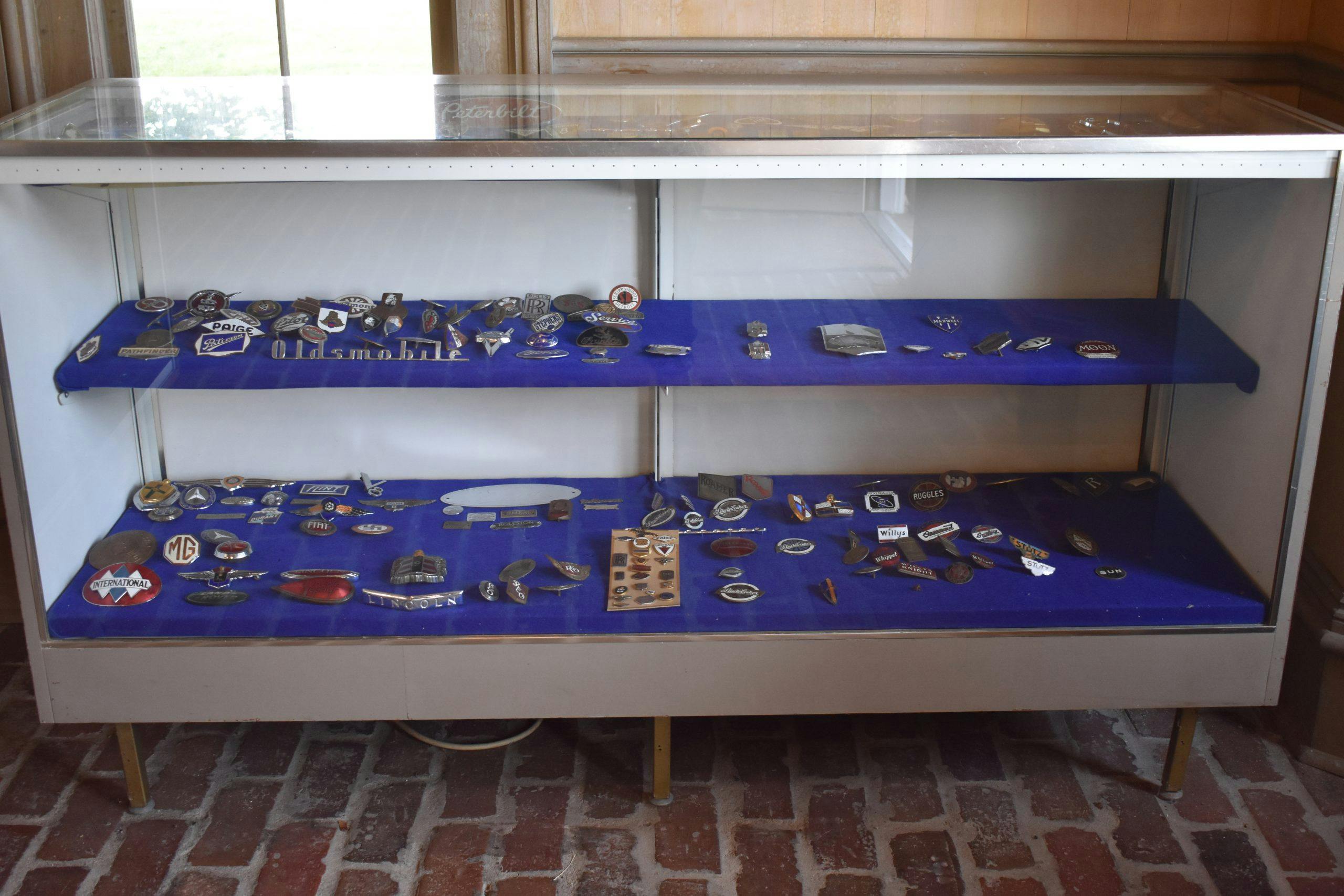

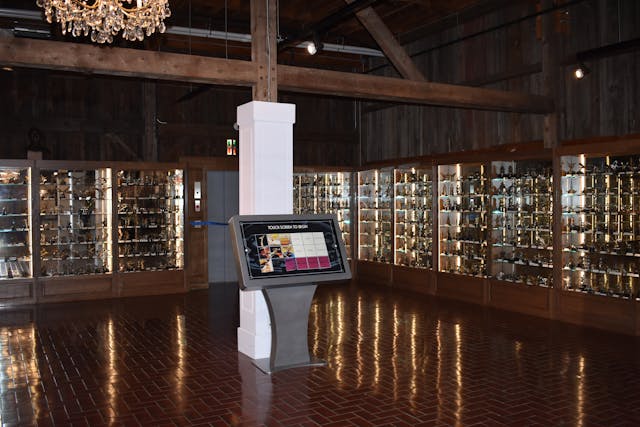

Tamaroff didn’t just collect these badges and figurines, either. An early member of the Classic Car Club of America, Tamaroff donated a collection of nearly 700 mascots to the CCCA’s museum within the Gilmore complex in Hickory Corners, a few miles north of Kalamazoo, Michigan, where they are on permanent display.

Tamaroff was born in Detroit in 1925. By the time he graduated from high school, World War II was raging and he went straight into the military. He found himself in combat in Europe by the age of 18 and spent six months in a German P.O.W. camp, where he contracted dysentery. After the war he returned to Detroit, where he enrolled in the General Motors Institute, GM’s in-house engineering and management college, known as Kettering University as of 1998.

When GM ran the school, a GMI diploma practically guaranteed you a job with the automaker. Tamaroff graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1949 and interned successfully with the company but, according to Tamaroff, his supervisor made it clear that he would never recommend hiring a Jewish engineer such as Tamaroff.

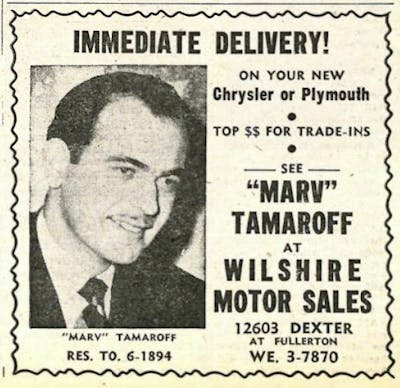

Still wanting to work in the auto industry, Tamaroff tried his hand at selling new cars, first at a Chrysler-Plymouth dealer and then at a DeSoto-Plymouth shop. He soon decided he could make more money in used cars, so he got a job on the famous row of used car dealerships on Detroit’s Livernois Avenue. He did well enough to start his own used-car shop, Marwood Motor Sales, in 1954, which he operated until 1969. That same year, he opened up his first new car dealership, a Buick franchise on Telegraph Road, in the Detroit suburb of Southfield, among what was then mostly woods and farms. Today, it’s part of a mile-long string of new car dealers on both sides of Telegraph.

Not only did Tamaroff break new ground with the location of his dealership, he was one of first car dealers to expand into owning a group of authorized dealerships for more than one brand. Over the years, that Buick store was joined, at various times, by Opel, Volvo, Mazda, Acura, Nissan, Isuzu, Dodge, Rolls-Royce, DeLorean, and Avanti. Tamaroff opened a Honda car dealership in 1971, one of the first Honda car franchises in the United States, starting with the 600-cc N600.

The Opel dealership is responsible for one of Southfield’s landmarks, “Tammy,” a lifesize replica of an elephant sitting in front of Tamaroff Honda, now painted red, white, and blue. The Honda store is located where the original Buick shop was—and the connection between the two is less strange than you might expect. In the 1960s, Buick dealers carried Opels so they’d have compact cars to sell. Opel advertised itself in the United States as the “Mini Brute,” and featured actual elephants in its ads. Opel has long since departed from these shores, but there’s still a pachyderm in front of a Tamaroff store on Telegraph.

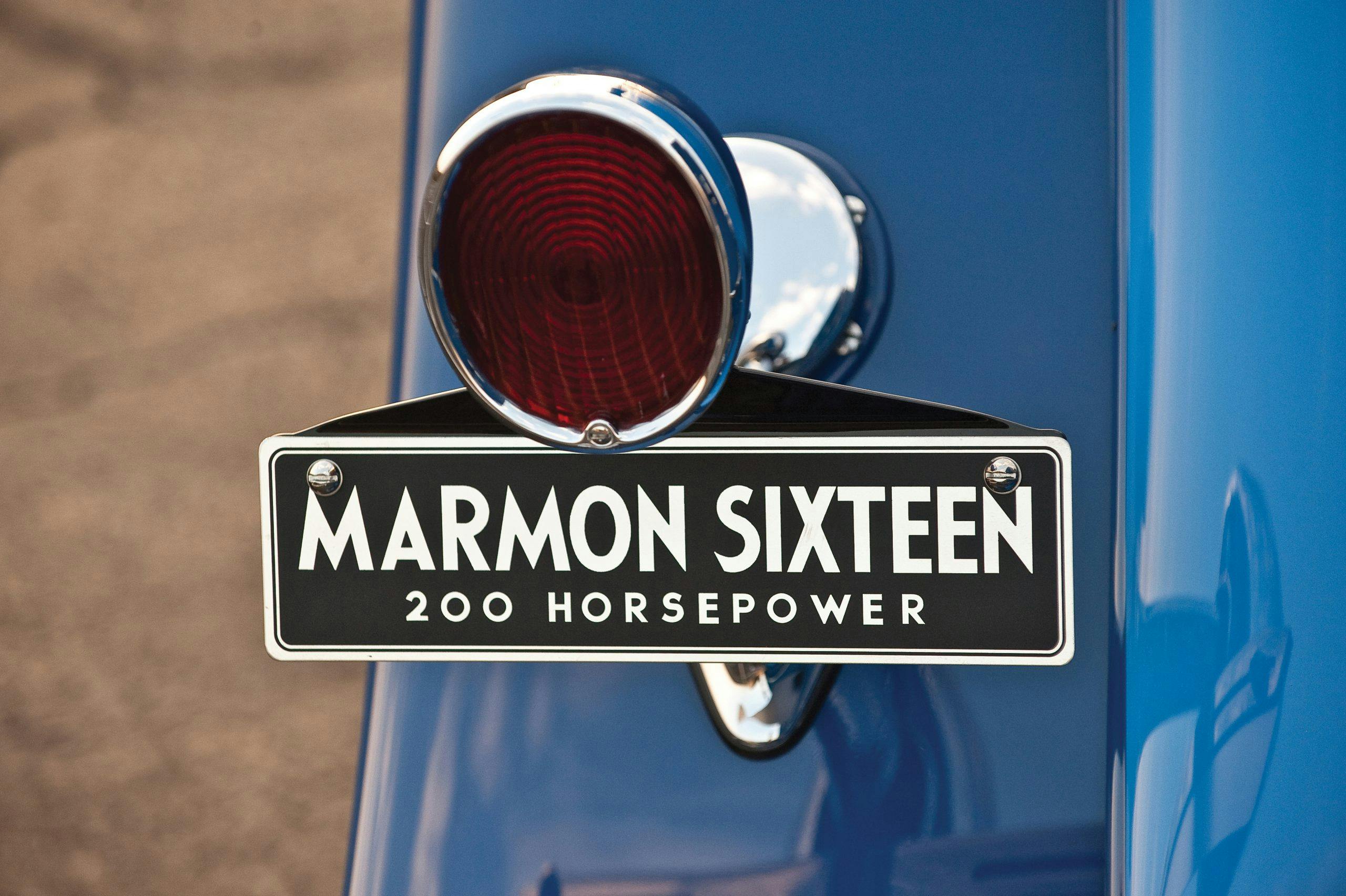

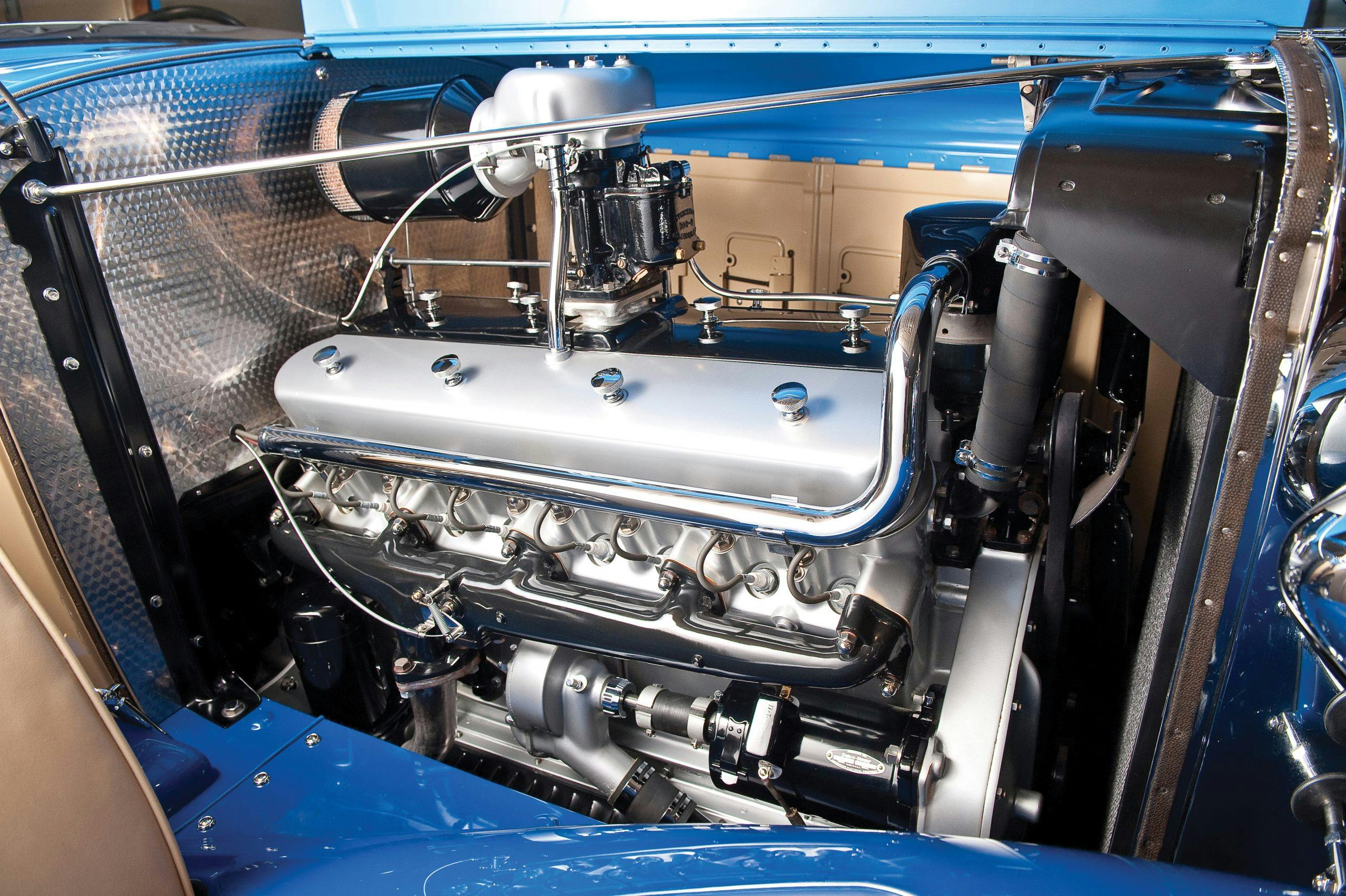

With his success, Marvin Tamaroff started collecting classic cars like prewar Packards, a Hispano-Suiza, and a show-winning 1930 Mercedes. His car-collecting hobby soon spawned an enthusiasm for racing trophies, which extended to a fascination with mascots and hood ornaments.

Today we call them hood ornaments, and associate them with specific vehicle brands, like Rolls-Royce’s Spirit of Ecstasy. In the early days, however, these emblems were called mascots and were as likely to be custom accessories designed to reflect an owner’s personality and tastes as they were to be supplied from the factory. Mascots sprang from the desire to decorate the rather plain radiator cap and ran the gamut from fine art created by famous sculptors to humorous caricatures. Judging from Tamaroff’s extensive collection, there was an entire menagerie of cast and chromed animals, jaguars, greyhounds, plus lots of birds, pelicans, cormorants, and storks. Putting a car on your car might be a bit recursive, but ships and airplanes made frequent appearances.

Tamaroff’s collection of mascots and hood ornaments grew to 1100 items, likely the largest of its kind in the world, including many rare, one-of-a-kind, sculpted pieces. He even was able to acquire a large, dealer-display version of the Spirit of Ecstasy, but, without a doubt, the jewels of his collection are the Lalique mascots.

René-Jules Lalique was a French jeweler who switched to working with enamel, glass, and crystal in the early 20th century, just in time for the automotive age. Starting in 1925, Lalique’s workshop produced a series of 29 glass mascots, many of them in an art-deco style, that became de rigueur on the radiators of upper-crust cars. Six years later, the Great Depression descended. Dropping cash on an ostentatious hood ornament was no longer in style, and the Lalique firm discontinued the mascots.

Today, though, they are highly collectible and very valuable, with auction prices reaching into the tens of thousands of dollars. Tamaroff is said to have amassed two complete sets of the Lalique mascots, one of which he sold at auction in 2000 for $550,000. A number of Lalique mascots are on display at the Gilmore, as is another very valuable mascot: the elephant that Rembrandt Bugatti sculpted for his brother Ettore’s cars.

One admirable thing about Marvin Tamaroff’s collection of mascots is that he didn’t focus only on the elite end of the hobby. The unusual and oddball hood ornaments that are part of the collection show that his passion for history included a sense of whimsy.

Tamaroff initially donated 520 of his mascots to what was then the Gilmore Institute and made further gifts over the years. When the Classic Car Club of America built its own museum in the Gilmore complex, the collection was put on display there. After recent renovations to the CCCA museum, including a new display devoted to the art of the automobile, some of the Tamaroff collection is now on display in the adjacent Hickory Corners train depot, along with the Owen Morton collection of automotive badges.

Any excuse is worth a visit to the Gilmore, but if you can’t make it to central Michigan, the CCCA has put the entire collection online where you can view each item individually.