Life is imperfect. Why should our cars be any different?

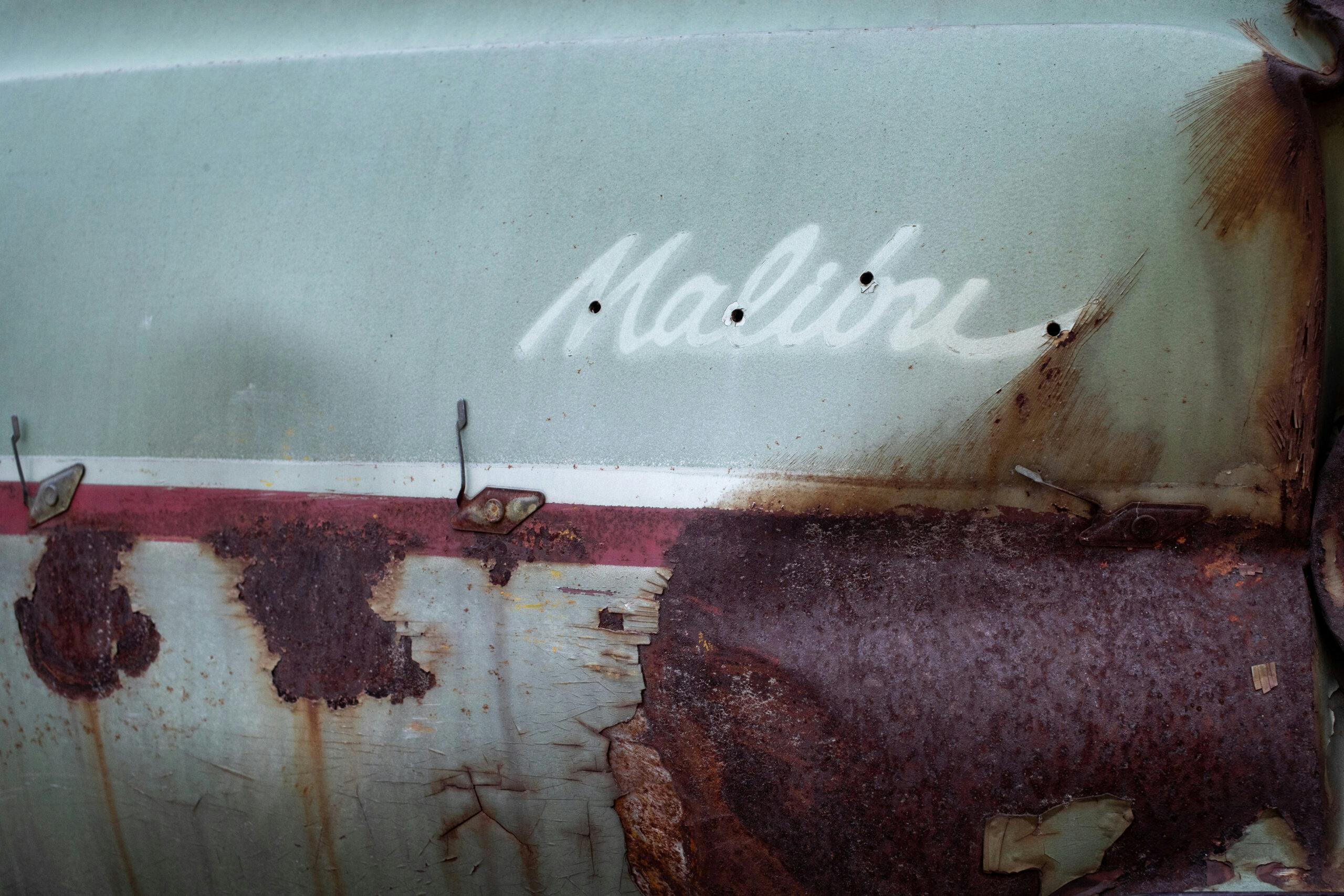

When we drive our cars, they collect signs of that use—patina, in collector-car speak. The latest issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, in which this article first appeared, explores the delight found in such imperfect cars. To get all this wonder sent to your home, sign up for the club at this link. To read about everything patina online, click here.

Look up at the night sky to see one of the best examples of patina in the known universe: our moon. It has been rolling up miles for the past 4.5 billion years and it is sun-faded and totally blasted with stone chips. Who knows, maybe someday we’ll get around to restoring it. In the meantime, we all know that the hands of the clock move in only one direction, and so far, nobody has figured out how to freeze time or, better yet, turn it backward. This despite thousands of years of noodling on the problem. And it is a problem because time marching on means age and decrepitude creeping in. We are aging and so is our stuff, giving rise to multibillion-dollar industries that promise—and uniformly fail—to stop it.

Patina. It’s the Italians, renowned for their metalwork going back to the Middle Ages, who get the credit for the word. It literally refers to a shallow dish but in common usage describes the layer of tarnish on metal—often a dish—due to oxidation or reaction to chemicals. Of course, patina goes back much further than the Middle Ages. Not long after some unknown artisan cast the first glittering object in bronze around 6500 years ago, it started turning green. And you can bet that the customer was pissed, initiating both the first warranty claim and a centuries-long assault on patina that traces a direct blood lineage to the Eastwood catalog.

The question we are attempting to raise is whether we should even bother. Because patina can be a lovely thing. Indeed, the second definition of the word patina in the Merriam-Webster dictionary is “a surface appearance of something grown beautiful especially with age or use.”

What makes an old, used thing more beautiful than a new, clean thing, exactly?

“You’re like the 400th person to ask me that question,” said Steve Babinsky, founder of Automotive Restorations, a Pebble Beach–quality restoration shop in Lebanon, New Jersey.

“I have no idea. There is no intelligent answer to that question. Personally, I like patina, but my customers don’t.”

Along with Henry Ford, who crammed a sprawling museum full of unrestored machines in the belief that technology should be preserved in exactly the condition in which it was used, Babinsky is a kind of disciple of patina. Meaning that he owns numerous original prewar classics himself, including an unrestored 1928 Lincoln with a Locke & Company–coachbuilt body that is currently buried in the shop behind a couple of freshly restored Duesenbergs. “People will walk right past the Duesenbergs to see this Lincoln,” he said. “It’s just more interesting to see how the old dead guys did it back then.”

Babinsky also helped start the preservation class at Pebble Beach in 1998 by entering a Belgian-made 1927 Minerva. It has a unique, impossible-to-restore fabric body, and it was the first original-condition car to enter the famed concours in decades. The preservation class was the institution’s recognition that patina (being the handmaiden of originality) has a place at the pinnacle of the classic car world.

Since then, it has earned a place at other rungs on the ladder, from Magnus Walker’s shaggy “urban outlaw” Porsches to the turbocharged, nitrous-fed rust buckets built by YouTubers like the Roadkill crew. Every year, the Antique Automobile Club of America features a class at its events called HPOF, for Historic Preservation of Original Features, which welcomes cars from all eras with original equipment. Originality is king and patina is no handicap. “People obviously come at this hobby from different directions,” said Steve Moskowitz, executive director of the AACA. “There are a whole group of us who enjoy being transported back to a kinder and gentler time than it is today. And seeing something unmolested is pretty cool.”

Patina on a Radwood (1980–99) car can especially be appreciated when it’s on a rare or high-dollar car. The key is wear, not neglect. Think Ferrari F40 with pitted paint on the nose and rear quarters and faded event participation stickers on the rear glass. — Art Cervantes, CEO and cofounder of Radwood

In common car parlance, “molested” refers to what happens to cars after they leave the factory. It’s perhaps an overly punitive term that can mean anything from miles on the odometer to a roof that has been sawed off. To be fair to earlier generations, pretty much every car built for the first half-century of the automobile’s existence experienced only depreciation. So nothing much was at stake. Cars didn’t really start appreciating in value until the past 40 years or so. Until then, a vehicle was there to be used in whatever manner the owner saw fit until it had no use, then it was scrapped. Indeed, during the two world wars, it was considered a dereliction of your patriotic duty not to scrap worn-out old cars.

And the real prizing of unrestored originals is an even more recent thing, growing in importance over just the past couple of decades. Maybe it’s simply another frivolous indulgence stemming from our postwar peace and prosperity. Nostalgia is the privilege of those who aren’t starving or fighting world wars. Another take might be that it’s a reaction to our modern throwaway society, where nothing seems to last except things made in the old ways (and which testify to that fact by bearing the patina of long and faithful service).

The most famous Barn Find patina car I’ve had was my Ford Country Squire wagon with a 428 and four-speed. I drove it across Kansas with a surfboard on the roof and half the people gave me thumbs up, and the other half thought I was homeless. — Tom Cotter, Barn Find Hunter Extraordinaire

Lance Butler of Los Angeles is 30 and daily drives a ’65 Mustang notchback that he bought from the original owner, the proverbial little old lady from—not Pasadena, in this case, but nearby Pomona. “Original cars are charming because they have a different spirit from a restored car,” said the McPherson College auto restoration program grad and professional mechanic and collections manager. “I’ve owned restored cars. Original cars show function and use—the history hasn’t been washed away.”

Butler likes the evidence of the Mustang’s previous owner. “You can see her habits in the car, where she put her arm on the armrest and where she scratched the steering wheel with her rings.” Butler also has a ’36 Ford that he bought from a guy who had owned it since 1950. “There’s a sticker on the window for his World War II squadron, and there were a bunch of pins in it, like ‘Vote for Willkie.’ There are stains in funny places, where people probably spilled a 5-cent cup of coffee. If you offered to trade me for a freshly restored ’36 Ford, I would say no.”

One of the foremost experts on and enthusiasts of patina is Miles Collier, founder of the Revs Institute in Naples, Florida, a museum and research archive devoted to collecting, preserving, and telling the story of historically significant road and racing cars. Many of the Revs cars wear their wear and tear with pride. “Patina is essentially everything when we’re dealing with relics from the past,” says the reliably quotable Collier, whose book, The Archaeological Automobile: Understanding and Living with Historical Automobiles, attempts to prove that there is indeed an intelligent answer to the question of why patina matters.

“One way to think about it is when objects are created, they are analogous to human children when they’re born,” Collier told us by phone. “We all look the same, we all look like Mr. Magoo. But by the time we’re in our 50s and 60s, we’re all palpably different from every standpoint.”

Likewise, said Collier, objects made in a mass-produced industrial environment are essentially all the same when they come off an assembly line. By the time they have experienced “the vicissitudes of life, they’ve been used, consumed, modified, changed, crashed, updated—all the things that happen to cars. They have gone from being one of a series of mass-produced products to being a one-of-one. They are uniquely transformed by their experiences, and those experiences are manifested in the patina.”

Patina isn’t like rain, descending from the heavens and wetting all objects the same, Collier continued. Every bit of patina on a car is unique and speaks to a very specific incident in its past, whether you know what the cause was or not. Patina gives an object a temporal dimension as well as a spatial one, which makes that object far more interesting, he believes. “That is as close as we can get to the reality of that object’s experiences over time. Why on earth would you ever mess with it?”

Besides, it’s important to remember that the clock never stops. A freshly restored car is the same as a freshly built car, in that both start aging the moment they are assembled. The scientific term is “inherent vice,” which is defined as the tendency of objects to deteriorate over time because of the basic instability of the matter from which they are made. In cars, plastics get brittle and crack, iron and steel rusts, rubber rots, glass hazes, and so on.

I think there’s an appreciation for a 200,000-mile Ford Pinto and there’s an appreciation for a completely restored Pinto. I don’t know that one is, you know, more respected than the other, because they’re equally as ridiculous. — Alan Galbraith, founder of Concours d’Lemons

A car is in motion even when it’s not—even if it’s parked on ceramic tile in a climate-controlled vault. “They all are on a downhill slide to oblivion at some point,” said Collier, “and that is something we need to know, and it makes owning these cars more of an obligation and at the same time is immensely freeing.” How so? Because any car acquires patina, whether it’s used as living room decoration, as a locked-away financial investment, or as it was intended, as a tool for mobility. Rather than fret about it and fight it, we really should be celebrating and participating in it.

OK, but if they were selling tickets in time machines to go back to 1965 and buy brand-new Mustangs out of the showroom, wouldn’t people like Lance Butler be first in line? Well, obviously that is impossible, and a car that attempts to go back in time through restoration, no matter how good or accurate the job is, “is for all intents and purposes a reproduction, a replica, a simulacrum, a facsimile,” said Collier. “All restoration is fictitious. I’m not saying that it’s a bad thing, I’m just saying that’s how it is.”

One reason is that any restoration done in the year 2023 brings with it a 2023 sensibility. “That sensibility automatically makes anything we do fictitious. Because we don’t see the world the way the maker saw it, or the way the user saw it, or the way the person who left it under the apple tree saw it.” Even if you can procure the exact correct paint, and paint it exactly as it was done originally, and chrome the bumpers with the exact same technique and materials, and so on, eventually you will come to points in the restoration where there is no choice but to “stick your finger in your mouth and put it up in the air and see which way the wind is blowing,” Collier said. Because you can’t go back in time and know everything that the people who originally built the car knew.

Yeah, but why does that even matter? A sizable contingent of the old-car world thinks like Babinsky’s customers and would argue that cars are best when they’re shiny and spotless. If not exactly new, then they’ll take a “fictitious” like-new on any weekday plus twice on Sunday. Certainly if the alternative is chipped, scratched, faded, dented, and fritzy. To be sure, owning and operating an original car brings its own pains. “They’re fragile things,” acknowledged Babinsky, whose oldest unrestored car is a 1903 Pierce-Arrow. “They are gradually falling apart.”

Fine, agrees Collier, there’s no problem with wanting shiny and reliable—that’s the owner’s privilege. And at some point, if the car is decrepit enough, it may tell its story better if it’s restored than if left original. That car’s journey toward patina, toward having a fresh story, will begin as soon as you back it out of the workshop.

But if everyone demanded shiny and new, we would be scrubbing away our own fingerprints on time. Patina “is the thing that humanizes cars,” said Collier, and that’s really what it’s all about for people who think like him. Machines in and of themselves are interesting, but like every other machine, a car is merely a tool, and “it’s the human-machine interaction, the human-tool interaction, the human-object interaction that is the critical thing that engages us. We love to see the tool, but we want to know how it was used, why it was used, what did the guy who made it think, what did the woman think, what were their fears, their interests, and so on. Those are the things that add flesh and blood to the object.”

So go out to your garage or driveway and behold your collection of rare, unique, ones-of-one. They are your fingerprints on time, your own flesh and blood as reflected in a machine, your proof that, like the moon, you rolled up a lot of miles and have the stone chips to prove it.

Then come back inside and keep reading.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Patina is a thing that just seems to suit certain vehicles well. And on the flip side, a lot of cars don’t look even remotely good when they start to age. It’s almost like it’s a thing that is very fitting for a vehicle that was built with the intention of being anything other than just a place-to-place piece of mindless transportation. Work trucks, muscle cars, off-roaders, race cars, etc. Anything that was built with the purpose of achieving a task. A beat-up minivan meant to just transport kids to and from soccer practice doesn’t have that sweet appeal.

There is a lot of uncovered distance in this article, and there is a whole lot of ground between rustbucket and museum quality restoration. It used to be that the respect “survivor” cars got was due to the excellent care they got over the years, so the thought was “how did that car stay so nice with original paint, interior, etc. over so many years?” Mostly, those thoughts went toward cars that you wouldn’t think would be candidates for such care. It is not surprising to see a beautifully preserved ’67 Vette 427/435 because it isn’t hard to fathom someone just putting that in the garage for future collectabilty. But when you see some older dude driving his inexplicably nice original ’67 Chrysler New Yorker, you figure that guy has been driving that thing for 50 years and probably has washed it every weekend and has a complete receipt file of every repair ever done on it since new. Survivor cars that have kept their original niceness in spite of the odds deserve the accolades, and deserve to be preserved that way. They are the basis for the phrase “it’s only original once.”

This modern trend of what has become “patina” was nothing more than a response to the fact that a decent paint job has become so f*@!$ing expensive, it doesn’t fit into the budget of a lot of guys anymore. You can’t justify blowing $40K on a paint job for a car that is worth $12,500 when it is finished. I think that was the start of the “rat rod” craze, in an attempt to legitimate the lack of a decent paint job – “it’s not that I couldn’t afford it, no I meant to do it that way, yeah that’s the ticket.” And people bought it.

Back in the late ’70s, the teenagers all had their rolling rainbow Chevelles and Camaros because they were $800 cars and the kids were desperately saving up for a paint job but could still drive the cars in the meantime. They got the used replacement parts cheap but had to wait to paint the car. As some of the other comments have said, a rusted out piece of sh@t is not a badge of honor, it is a sign that the car has been neglected over the years. These cars used to be called “parts cars” back when you could do a “2 to make 1” project. Now, some of the cars that are in this “patina” category would have been considered too far gone to be a decent parts car.

I love people being in the car hobby however they can, and I do get a kick out of seeing these “very experienced” cars still on the road, but I think the whole patina thing is getting too much credit. And, fake patina is definitely going too far.

Yeah, not for me. Patina is something to be avoided, which is why we fix dents, replace broken trim and cracked glass, wash & wax, etc.

There is a distinct difference between a “well preserved original” and an “old jalopy.” (My wife recently referred to my well-maintained and restored #2 ’63 Bonneville convertible as a “jalopy,” and I had to educate her as to the meaning of the word.)

Faux patina (when not disclosed as such) is bad for a different reason: Like the look or not, it’s akin to stolen valor, and not something to be lauded. I could slap a “This car climbed Pike’s Peak” sticker on my bumper, but if my car didn’t actually *do* it, that’s simply being dishonest.

Anyway, in a word, yech.

I say that there is a difference between between what we call ‘patina’ (think we got that from the Antiques Roadshow!) and just plain wreckage! Call me old school, but once a car — in it’s totality — was an expression of our best efforts. It said “Look what I can do!” in the earlier days of hot rodding, not ‘Look what I can put up with in the way of rust, bondo, and nastiness!” We always built our rides to the limit of our skills and resources, and if your car had primer spots until it’s last day, that was okay if you considered it a work in progress. Yes, I know that a lot of those ragged bodies hide $30K of high-tech chassis and powerplant, but it’s still not going to make me cross the aisle at a show or gathering, sorry. If there’s another cat who has done better with his ride, even if obviously a low-budget effort, it takes my vote! Ragged rat-rods vs. $200K billet beauties; neither has much reality to me. I M Humble O.

I had a 68 Jaguar E Type FHC completely restored with many performance upgrades including an aluminum covered headlight bonnet.

At first my reaction was that after owning it for over 40 years it was not my car anymore and had lost its soul.

Now after 4,000 miles she has regained her personality and usage patina is slowly and carefully coming back.

My ’70 Eliminator sits right at the crossroads where “patina”, “survivor”, “unrestored” and “needs restoration” meet.

It presents as “unrestored original” with that “been there, done that” vibe that we love about a patina’d survivor. But it’s not original paint, it’s just OLD paint. Factory color, yes, but 4 shades of it sprayed over dozens of years and several different spells of bodywork needs. …but it was all done “back in the day”, and now closer look shows failing bondo in several places, as well as brazing and rivets used in past body repairs!

Folks see it and exclaim “oh man, what a survivor!” and I’m like… “yeah, it survived A LOT!” But it ain’t no cream-puff survivor. Somehow it survived being scrapped from several accidents that would have sidelined most cars. It has the look of a car that was loved and driven, and when it needed help it was repaired and put back to work on the streets.

I’ve toyed with the commitment that a full restoration requires, but I frequently take it to cruises and meets where it always draws attention and I can’t count how many times I’ve been told “oh man, don’t change a thing!” And I can empathize with that too since it’s only me that sees all the flaws that a hard life has wrought on this old car.

So for now, while I sit on that fence, I’ll just keep driving it and enjoying it, and doing what I can to mitigate the effects of age and use.

[url=https://imgur.com/kLWAkkk][img]http://i.imgur.com/kLWAkkk.jpg[/img][/url]

I love this article about the not so pristine vehicle, as I am the proud second owner of a ’65, Wimbledon white, Mustang notch back that my father purchased new in first week of April of the same year. I was a teenager then and unable to drive it as my father used it as his daily driver, relying on it for his thirty mile each way to work. The car was eventually being driven by five family members as it acquired its “patina”! I was so upset that he bought it with only a six-cylinder and automatic,; as I was longing for the 289 and four on the floor. His answer , as an aeronautical engineer, was for economy of operation, reliability, and not getting speeding tickets, as he had a ‘heavy’ foot in his past two cars. This Mustang has over 200,000 miles on the body; around 25,000 miles on the rebuilt engine/transmission (yr 2000) and is garaged in the same location it was when brought home from dealership that April ’65. I took possession of it in 1984 as my sister, living up north of us, decided she wanted a newer, more reliable and up-to-date vehicle. I remember my father saying to get “rid of that old car”, as it was just a used transportation conveyance, nothing more in his estimation. I saw something that was more than utilitarian, and maybe it may appreciate in time and having joined a car club, it was fun to drive and show others in the club, who were impressed with its survivor status. It has been fairly reliable and a backup to my daily driver. Many people give me the “thumbs-up” while driving it around town and many inquire about acquiring it. I just smile an say, no thank you. Being a California auto it has no appreciable rust and the hood,top and trunk paint is still free of major scratches or dents and even shiny. The sides have quite a few minor dents and scratches, and less than luster paint ,mostly from encounters from the parking lots over its fifty-eight year life in the real world, therefore “patina”.

They are only original once.