Why racetracks are giving hybrids and EVs the cold shoulder

This is a tale of two racetracks, and how they handle—or don’t handle—electric and hybrid vehicles.

First, Atlanta Motorsports Park, in Dawsonville, Georgia, which features a Herman Tilke-designed two-mile road course.

“Electric vehicles are the future of racing,” says Jeremy Porter, AMP owner and CEO. Not only are electrics and hybrids welcome at AMP, Porter has installed five new Autel MaxiCharger DC Fast Level 3 chargers for his customers to use. “From hyperexotics to luxury vehicles to EV retrofits, everybody who comes to AMP deserves speedy charging off-track so they can get back to shaving off their times on-track.

“Our long-term ambition is to be an incubator for using mobility technology. Currently we have three EV technology companies at Atlanta Motorsports Park, and installing Level 3 chargers crystallizes our commitment to this tech.”

About 477 miles northeast is Summit Point Motorsports Park, a two-mile, natural-terrain road course in West Virginia that opened in 1969. Summit Point’s director of motorsports operations, Edwin Pardue, has banned the use of electric vehicles and hybrids on track.

While he says Summit Point supports electric technology when it comes to racing, the track has taken a “‘tactical pause’ in halting the use of electric and hybrid electric vehicles in all motorsports disciplines at our location,” until it can establish an emergency response policy that makes sense for a small track in a rural area.

Pardue is not alone. Carolina Motorsports Park, in Kershaw, South Carolina, which has a 2.27-mile road course, abides by a simple rule on its books: “No electric vehicles allowed on track.” A relative handful of other circuits have followed suit.

Shortly after Pardue announced the electric ban, the National Council of Corvette Clubs announced its own ban affecting the new Chevrolet Corvette E-Ray, which uses electric hybrid technology to power the car’s front wheels, while a conventional V-8 sends power to the rear. The E-Ray isn’t on sale yet, but Bill Docherty, the Council’s vice-president of competition, said they wanted the rule in place “before the E-Ray was available, so members do not expect to compete if they buy one.”

The NCCC went even further than Summit Point, stating that if you bring your E-Ray to a motorsports event, you’ll be required to park “30 feet minimum from buildings and other cars.” Over the weekend, apparently, the NCCC board reversed course and now the E-Ray (and other hybrids) will be allowed full participation. But the original ban—which still applies to pure EVs—got a lot of publicity and started a conversation regarding what the policy toward electrics should be.

Most electrics are powered by lithium-ion batteries, which consist of small battery packs nestled closely together. The number depends on the design and size of the battery; some Teslas have almost 8000 cells, while GM’s Chevrolet Bolt has 288 larger ones.

Battery fires are rare yet often make for big news when they happen. The fires burn bright and hot, as the batteries can suffer from “thermal runaway,” a phenomenon by which one small battery pack overheats or ignites, which overheats the battery pack next to it, and the one next to that one.

Regular fire extinguishers don’t work in these cases. Most fire departments use one of two methods to deal with a battery fire: Douse it with water to cool it down—generally a lot of water, between 3000 and 30,000 gallons, depending on the incident. “Cooling takes 100 times more water than a gasoline fire,” the NCCC’s Docherty said.

The other method is to just let the fire exhaust itself, a guard against re-ignition once the battery stops burning. One method to prevent re-ignition, more frequently used in Europe, is to pick the smoldering car up with a forklift and dunk it in the water.

One of the highest-profile battery-defect cases in the U.S. right now concerns the Ford F-150 Lightning; production was halted until the company and its battery supplier addressed a fire that began in one new, parked Lightning, and expanded to two others. Another concerns the Chevrolet Bolt, which was recalled after 18 examples caught on fire.

The Lightning and the Bolt are not the only vehicles to suffer recalls related to battery fires. Automakers that issued fire-related recalls include BMW, Chrysler, Hyundai, Mitsubishi, and Tesla. Other industries have had recalls of lithium-ion-powered products as well, including computers and electric scooters.

The recalls are largely addressing thermal runaway issues, which often occur when the vehicle is stationary and charging. It doesn’t address fires caused by a damaged battery, either from a collision or running over a serious piece of debris. Automakers surround the battery with high-strength containers to protect it, but in some sort of devastating crash—the kind you might witness on a racetrack—the battery may still be vulnerable. Gasoline cars are vulnerable to these same risks, but extinguishing them is more straightforward.

Summit Point and the 19,000-member National Council of Corvette Clubs are concerned about both thermal runaway and damaged battery fire scenarios. Not only because of the possible injury to drivers, spectators, or corner workers, but to property. A serious battery fire on a racetrack can damage the surface to the point where repaving might be required, thus shutting down the track until repairs are made.

Are Summit Point and Carolina Motorsports Park outliers? Probably not. “It’s too early to call anyone an outlier,” says Heyward Wagner, director of experiential programs for the 51,000-member Sports Car Club of America. He is in charge of the SCCA’s “Track Night in America,” the program for which the club rents out a facility and lets enthusiasts drive their cars on track, typically for about $150. Wagner has Track Nights at about 30 tracks in the U.S., and so far, three tracks have told him they don’t want battery-powered cars.

Owners of cars like the Ford Mustang Mach-E or the track-ready, 1020-horsepower Tesla Plaid can’t participate. Under such restrictions, neither could supercars like the Porsche 918 Spyder or McLaren Artura. “Everybody is learning right now,” Wagner says. “We do have tracks that have told us that electrified vehicles are not welcome, and a track where they asked owners of electrified vehicles to sign a unique waiver.”

It’s a problem, Wagner says. “What is known is that an electrified vehicle fire is a different animal than an internal combustion engine fire. Nobody debates that. It requires different equipment, it requires different training, and that represents an investment for a track to make to be future-forward.

“It’s also an investment that municipalities have to make just to deal with what vehicles are on the road, and will be on the road in the future. The good news is that the technology that needs to be developed is being developed at a societal level. This is not just a challenge for motorsports.”

It’s not surprising, he says, “that different tracks take different approaches. We have 130, 140 years of data on ICE engines and fires. And maybe 10 years of useful data on electrified vehicles.

“One of the most important things for enthusiasts to keep in mind here is that the inclusion of electrified vehicles is very important to the sport’s future. I think electrified vehicles are engaging an entirely different mindset and demographic of enthusiast. There’s a tech angle that draws people in that an ICE vehicle probably wouldn’t. There’s also a reality that for this sport to be ready for the future, we need to be able to get out of the line of fire, no pun intended, on questions regarding environmental impact.

“Noise [for example]: There are so many things tied to that sound that so many of us love, that are potentially detrimental to our sport. Autocross in particular … the ability to acquire and retain sites just because it’s quieter will be significantly impacted in a positive way. And some tracks, like NCM Motorsports Park in Bowling Green, Kentucky, have had to go to great lengths to continue their business with the neighborhood’s sound regulations.”

Electrified vehicles present an opportunity “to be better citizens and better neighbors with that technology,” Wagner says. “It won’t be a flip of the switch from ICE to EV, but it’s technology that could make our space significantly more accessible and bring a lot more people to the sport. It’s really important for us as an industry to figure out how to solve this.”

The good news: Both motorsports and the public-private sectors are working on the issue, says Eric Huhn, facility and laboratory safety engineer at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. Huhn has also been a volunteer firefighter since 2015, and he’s well-versed on battery fires. Last month, he taught a Racing Goes Safer seminar on the topic at the Long Beach Grand Prix.

“I’m hearing more and more about tracks that won’t permit EVs and hybrids, and I’m not surprised that tracks are taking this stance,” Huhn says. “Out on the streets, the fire service is getting more and more experience with battery fires. And that experience is telling the fire service that these fires don’t behave like the fires we’re used to.

“The chemical reaction happening in a lithium-ion battery fire is completely different from how oil fires, or fires involving composites, work. That being said, you’re many times more likely to have a fire in an internal combustion vehicle because of all the flammable liquids. But those fires are easier to manage.”

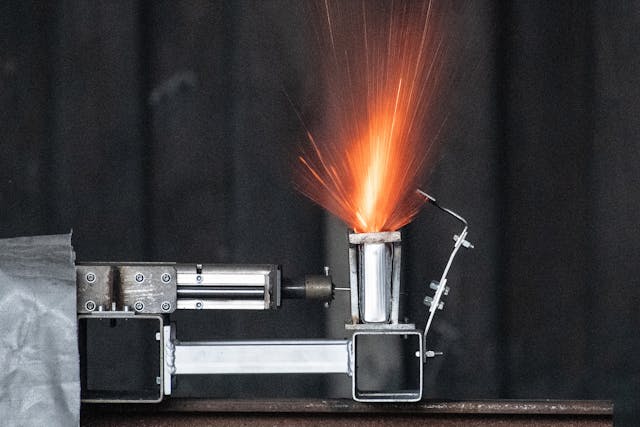

If a track doesn’t have near-immediate access to city or county fire services, asking a facility to have a 3000-gallon pumper tanker in the fleet is unreasonable. There are some new technologies that have shown promise; both the Rosenbauer Battery Extinguishing Technology (BEST) and the ColdCut Cobra involve piercing the battery box from the bottom and injecting water into it to cool the cells. The BEST system is remote, with the operator 25 feet away, while the ColdCut system requires a properly outfitted firefighter to get a little closer. It uses a thermal-imaging camera to show where the hot spots are in the battery, and the ColdCut operator proceeds from there.

Both systems require far less water than simply dousing the car and the battery with thousands of gallons. The ColdCut Cobra can be mounted on a small, specially-designed fire truck that does nothing but fight battery fires. That may be accessible for a racetrack, once track-related interest is great enough among electric car owners to justify the expense.

But for now, expect more tracks to ban or limit the use of electric and hybrid cars. “I really can’t blame them,” says the SCCA’s Wagner.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Well there is more to this than just fires. To be fires are no more common but yes they need to be prepared to deal with them in special training to deal with it. Most small tracks use volunteer fire and safety so most may not have the latest EV training.

But the big elephant in the room is shorts. Cars can be in a crash and no fire but the body of the car could be shorted and electrified. Safety crews needs to be trained in how to deal with and shut down these power systems no more different than shutting down a run away engine after a crash.

They also need to be able to know if the car is safe to touch. Unlike a shut off switch these cars could short to the body and make them unsafe to touch.

Friends with NHRA in a pro class told me about their runs in the EV Mustang Ford was showing. It has a light on the body that tells the crews it is not safe to touch. The light detects any short to the body of the car.

These challenges are just things that need to be learned before things get too far along. Safety needs to come first and training and investment in some new safety items will fix this.

All production EVs and Hybrids have internal protection that isolates the battery if any shorts are detected. The battery housing, motor housing, controllers, inverters, and cables have a ground-fault loop in them. If anything is damaged and that ground circuit is energized a breaker pops and isolates the battery.

You still need to be able to insure those systems functioned properly. Many houses have burnt down because breakers didn’t trip when they were supposed to. You have to ensure safety, not assume safety.

I don’t think that you understand electricity very well. Have you never heard of a ‘circuit’?

This article is out of date. The NCCC already reversed their decision after GM showed them test results with the eRay

See this paragraph, which also links to our coverage of the reversal:

“Over the weekend, apparently, the NCCC board reversed course and now the E-Ray (and other hybrids) will be allowed full participation. But the original ban—which still applies to pure EVs—got a lot of publicity and started a conversation regarding what the policy toward electrics should be.”

Funny F1 WEC & now IMSA

all have had Hybrids for years were is the outcry? Simply BS

Have you seen the precautions that IMSA and WEC are now having to take? Specific zones where the car must be pulled off into if it has an electrical issue. A light on the vehicle showing grounded or shorted – if shirted, driver has to remain in place and special personnel have to be called in to safe the vehicle. Track and Emergency personnel extensive new training and new equipment. Just as the article states – large tracks and Entities can afford to do this.

What has AMP done to handle these unique safety issues introduced by allowing EVs on track?

Yes! Can AMP handle the amps?

B^)

I’m not sure why EV/Hybrid people don’t just have their own events. They wanted the cars, let them organize their own events and have the equipment and training for dealing with their cars issues. They are pushing a lot of expense onto tracks that are probably operating marginally anyway.

Agreed!

I agree, let the ev’s start their system and pay for it themselves. I don’t think electric is our answer and it is unsafe when damaged or on fire. Electrocution of the drivers and safety crews is a real problem.

Agree with all of the above!

Please link me a single story of a thermal runaway fire or electrocution of a worker, driver, or emergency personnel from an EV or Hybrid even on a track anywhere in north America, ever. I’ll wait.

Separate but equal. That sounds familiar.

I don’t see anything in the above discussion about being equal.

The type of car you choose to buy is not a protected class…

And the tracks can’t sell any race fuel to them at $10, $15, $20 per gallon and that cuts into the income from racers.

I build complex Lamborghini and Maserati engines as a hobby ! I am also an Electrical Engineer…the issue is simple… a bone stock Tesla will blow the doors off expensive IC cars !

The IC guys who really can not even change their own sparkplugs, are pushing hard for keeping EVs out !

This sounds like the haters making excuses. I guess it hurts getting your gas guzzling Hellcats and Vettes spanked consistently by high dollar Teslas. Like it or not, the EVs are coming. AMP has the right idea and they are the future. It won’t be EVs getting banned. It will be the out of date, dirty and noisy tracks that disappear. It’s just a matter of time.

Hey Dave…..see my reply to Estelon

There are different racing classes for a reason. Why would an EV racer wanted to race an ICE if you know its no competition. Just because they both look like cars doesn’t make them equal. No different than a man who looks like a woman competing in woman’s sports. If you really want a challenge stay in your own class with all EV’s instead of looking for the easy win. What good are those bragging rights.

Not shocking (pun intended) what is going on. Tracks are not prepared to put out the fires that can happen.

Just like there is different type of racing / vehicles, there SHOULD be different racing for any other types of “race cars”. The PUSH to shove EV’s into automotive racing is simply a way to attempt to legitimatize them period. Once again, my clear thinking and good typing skills have made the Stasi complain that I “comment to fast”.

I don’t know my ZL1 has out run all the Teslas that have challenged it(at high speed, not off the line). I thought the reason to own hybrids was for environmentally friendly transportation. Why are we stressing the grid for a motorsports application? Partisan opinions aside I have been flying model airplanes with lithium batteries for 25 years. Puffed batteries and low cycle. Life are common; fires are not. The model airplane community racing battery powered craft have a safety precautions in place which work well. The procedure during electric race(EF-1 class) is the crash occurs the race is suspended, and the downed craft is found the battery, isolated and inspected for damage. If a fire occurs we use halon fire extinguishers and sand. We don’t have fire trucks on standby at our Fields!

I see no mention of Formula 1 which are the ultimate hybrid cars. As well as Formula E which are pure electric. Maybe we should be looking to the FIA for guidance. They have set procedures in place for extrications from hot cars (shorted or hot red light on). Green light on is no battery or electric shorting or issues. I have seen many bad crashes in the hybrid era with no major battery issues since a garage fire in 2012 by Williams. If your going to race a hybrid or an electric your battery case should conform to FIA standards. Safety First!

The Pantera community had their own similar problem 2 decades ago, when a stock magnesium rear wheel ignited during an event. After unknowing firefighters dumped water on the blazing car and the extreme heat broke the water down to hydrogen and oxygen thus intensifying the fire, the owner/driver, the firemen, and all the spectators watched the car literally burn to the ground from a safe distance. It took longer than you’d expect….

It was a fluke occurance- it never happened to them at LeMans in the Gr-4 class, for instance but photos made the cover of Autoweek magazine. Firefighting is a job I never lusted after!

I’m going to start by saying that I am a 66 year old ‘gear-head’ and I have been in solved in racing (in one form or another)since 1978 and have been fortunate enough to have raced vintage sports cars for many years. Racing is racing…no matter what it is you race! That is how the whole game started, and that is how it will end…if we let it happen.

All forms of racing are facing ‘pushback’, and many race facilities (even well established historic tracks) are in danger of being shut down. In my view, new technology is not the greatest threat to tracks. Greedy developers along with governments (of all stripes) looking for increased tax revenues are a much greater danger to racing. In some cases historic and well established race facilities that have been in place for many decades now find themselves under attack.

With respect to new technology, the larger facilities (with deeper pockets) are in a better position to address the inevitable future that will see more hybrid, pure electric, and perhaps ultimately the ‘cleanest of future technology as well as fuel delivery, hydrogen power. They do so because they realize that there future (both financially as well as philosophically) is to address the realities of dealing with future technology, and in the case of racing, the consequences of things going wrong as a result of pushing the cars to the limit. Smaller tracks will have to do what they can to simply deliver a safe track/racing environment based on the training and technology that they have access to for as long as they can.

I would humbly suggest that rather than bickering amongst ourselves over which technology is appropriate (everything mechanical is constantly in a state of evolution) as racers we will ‘collectively’ be in a better place if we all band together to do whatever we can to make racing facilities viable. The more people interested and actively participating in racing (what ever they choose to race) the better the chances we have of keeping racing facilities alive and running. Keeping tracks alive is all about them being able to generate revenue…in what ever form.

As racers, if we don’t ‘collectively’ get our act together, then we will soon have no tracks to run on.

Best comment here. Thank you for this Douglas.

So true, look at all the track closures this past year alone. Car guys need to take a page out of the bikers handbook. They lobby as one regardless of brand affiliation & they get things done.

Fantastic assessment

I’m going to start by saying that I am a 66 year old ‘gear-head’ and I have been in solved in racing (in one form or another)since 1978 and have been fortunate enough to have raced vintage sports cars for many years. Racing is racing…no matter what it is you race! That is how the whole game started, and that is how it will end…if we let it happen.

All forms of racing are facing ‘pushback’, and many race facilities (even well established historic tracks) are in danger of being shut down. In my view, new technology is not the greatest threat to tracks. Greedy developers along with governments (of all stripes) looking for increased tax revenues are a much greater danger to racing. In some cases historic and well established race facilities that have been in place for many decades now find themselves under attack.

With respect to new technology, the larger facilities (with deeper pockets) are in a better position to address the inevitable future that will see more hybrid, pure electric, and perhaps ultimately the ‘cleanest of future technology as well as fuel delivery, hydrogen power. They do so because they realize that their future (both financially as well as philosophically) is to address the realities of dealing with future technology, and in the case of racing, the consequences of things going wrong as a result of pushing the cars to the limit. Smaller tracks will have to do what they can to simply deliver a safe track/racing environment based on the training and technology that they have access to for as long as they can.

I would humbly suggest that rather than bickering amongst ourselves over which technology is appropriate (everything mechanical is constantly in a state of evolution) as racers we will ‘collectively’ be in a better place if we all band together to do whatever we can to make racing facilities viable. The more people interested and actively participating in racing (what ever they choose to race) the better the chances we have of keeping racing facilities alive and running. Keeping tracks alive is all about them being able to generate revenue…in what ever form.

As racers, if we don’t ‘collectively’ get our act together, then we will soon have no tracks to run on.