Spool’s errand: Fighting sameness with boost and bravery

Aside from stickers, every car starting the 2020 Indy 500 was dressed in an identical Dallara IR-18 aerokit. In the upper echelons of motorsports, disparity has become the exception, rather than the rule. Tight rulebook equals tight racing, which sanctioning bodies determine to be the best (and most profitable) dynamic for the sport. Slim margins require teams to spend more cash searching for tenths. This isn’t a new phenomenon, either; the message has been clear since Dan Gurney first penned the White Paper in 1978. As the rule books swelled in girth, gray areas fizzled out. The resulting race cars, from full-bodied stockers to rear-engine open-wheelers, became less distinguishable from one another, and more expensive, with each passing season.

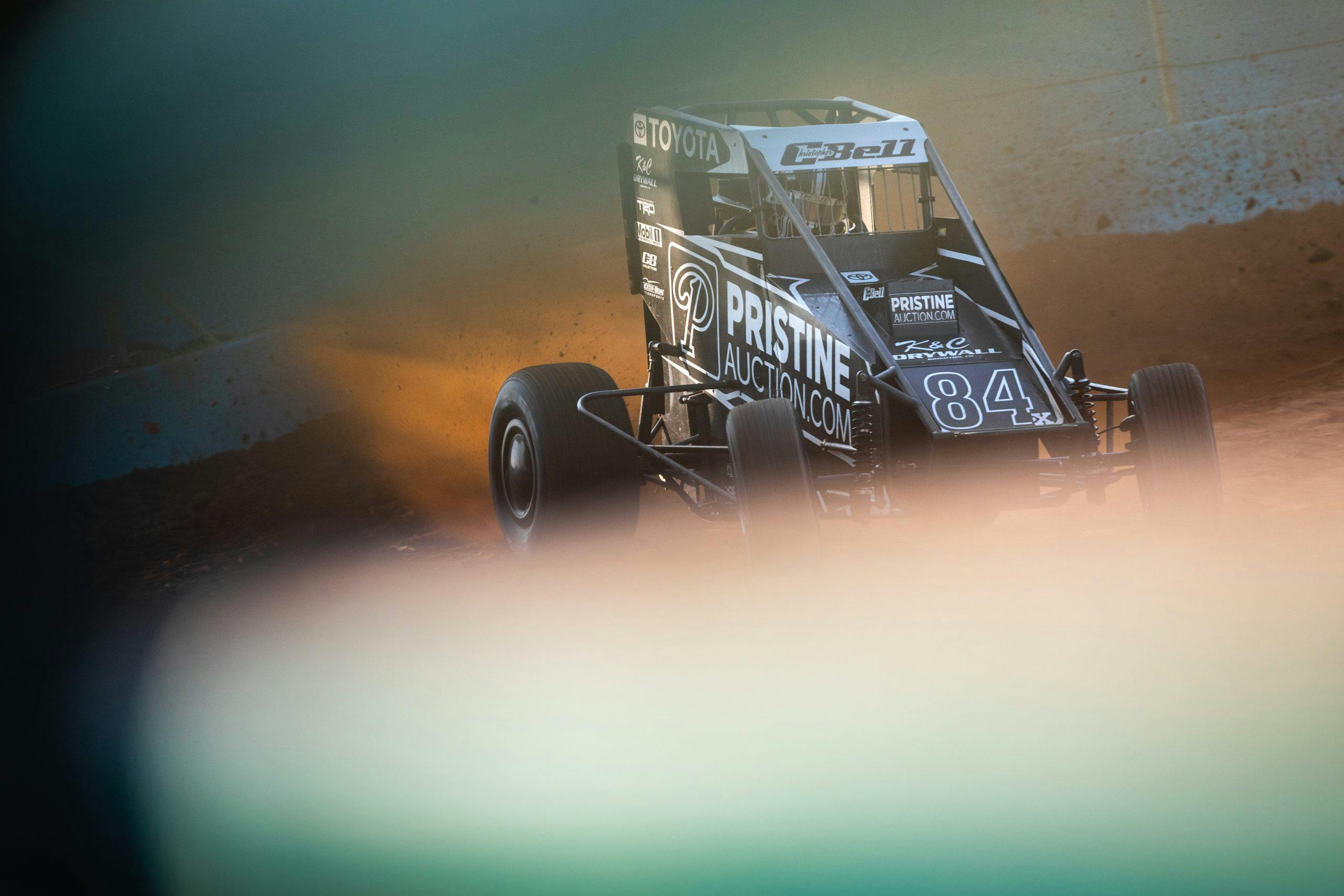

For the variety that many feel is the spice of competition, there is hope at the lower tiers of motorsports. Namely, midget racing. Running on pavement or dirt, these small, four-cylinder-powered race cars with their single-speed torque curve require drivers to be smooth, and the open-wheel layout demands careful car control (lest you hop tires and tumble).

Even these pint-size machines are subject to equalizing regulations from sanctioning bodies, but changes in midget racing are happening more slowly than in, say, NASCAR or IndyCar. Historically, any grid-walk at a midget race showcased a cornucopia of body panels, engines, and chassis geometries. Now, hot midget setups can be boiled down to a few different chassis-engine combos. Still way more diversity than their open-wheel Indy counterparts, but nevertheless dwindling. Lucky for the tinkerers, mad scientists, and modern-day Smokey Yunicks, midget rulebook margins haven’t been completely accounted for, leaving space to play and, maybe with a little luck, impart a lasting impact on the midget racing landscape.

The first midget race was held in 1933 at Loyola High School Stadium in Los Angeles. Crowds grew quickly and before too long, purpose-built arenas like Gilmore Stadium across town hosted midget races. Miniature Kurtis Kraft roadsters, powered by Offenhauser four-cylinders or Ford V8-60s, dominated the scene. Future hot rod magnates like Vic Edelbrock converged weekly on the So-Cal speedrome to campaign their own scratch-built cars. Young scrappers like Roger Ward, A.J. Foyt, and Parnelli Jones banged bumpers around dusty quarter-mile bullrings.

From mid-century the ’70s, as with most forms of motorsport, experimentation experienced its peak. Maximum displacement was often the only rule that engine builders had to follow. Power came from Chevy, Volvo, BMW, Ferguson (yes, the tractor company), and even Evinrude outboard boat motors. The same 1600-cc dual port long block VW engine, shoved in the aft end of sandrails and Formula Vee race cars, became a favorite among midget races. SESCO engines were the result of engine builders cutting V-8s lengthwise, while some opted to cut their blocks cross-wise for a V-4. Jeff Gordon got his first ever open-wheel win in an Iron Duke-powered midget.

These days it’s largely the Toyota and Chevy dance at midget events, as those manufacturers provide engine builders with purpose-built blocks. Esslinger, Stanton, and other midget motor houses riff off an aluminum inline-four block ranging from 2.4 to 2.7 liters, delivering anywhere from 350 to 400 horsepower. (Stanton puts a Mopar head on what is essentially a Toyota TRD block.) These engines provide big power, albeit at big cost. Want to remain competitive and perhaps qualify for the big show at the Chili Bowl (midget racing’s Daytona 500)? Better be prepared to plunk down 50-large.

If you have two kids that want to go midget racing, we’re talking six-figure money in engines alone. This was exactly the problem Charles Breidinger faced. A mechanical engineer and outright gearhead from Southern California, Breidinger was not about to let cost impede his daughters’ racing dreams. Naturally, he built an engine of his own.

Breidinger was working on a naturally aspirated Honda four-cylinder for a smaller midget series—a feeder for the feeder, if you will. The 2.4-liter Honda four-banger often plucked from ninth-generation Civics costs significantly less than a big-time midget engine, but it could at most eke out 350 horsepower. Fifty fewer horses represented an insurmountable delta between Breidinger and the podium teams.

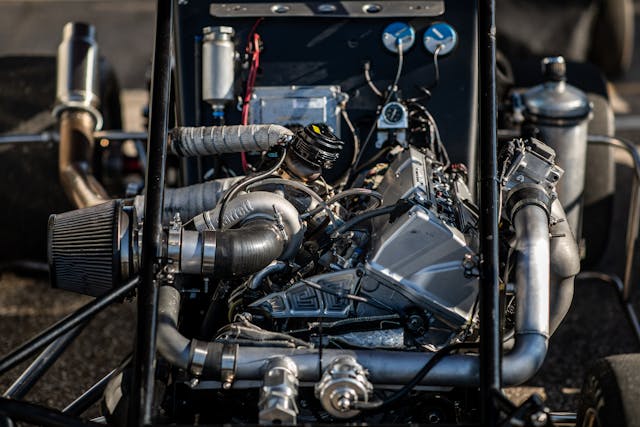

Inspiration struck at dyno shop in Richmond, California. While testing his Honda powerplant, Breidinger watched some heavily tuned and turbo’d Civics roll up on the dyno and pull close to 400. The only difference between his engine and theirs? A turbo. Eureka! Breidinger tore into the catalogs, looking for a small turbo that could spool quickly, so his daughters squashing the gas could ride a wave of boost on straightaways. He eventually found the Garrett G25 turbocharger and backed it up to a single-port head on top of the Honda block.

“At one time turbos were considered exotic, expensive, and hard to control,” says Breidinger, “but now that tech has evolved, it is less expensive to build a turbo’d engine over a naturally aspirated engine.” The tech wizardry with these engines largely relies on ECU tuning, and from a laptop he can control ignition timing and boost settings. Since he also has Honda’s variable valve timing (VTEC) in an engine that now produces 400 lb-ft of torque, Breidinger says turbo lag is also a thing of the past.

By limiting the boost to around 10 psi, Bredinger can also hit that magic 400-hp figure. The 8000-rpm-screamer runs on 100 percent methanol to keep the whole package cool. All told, he has about $20K dollars into the engine—less than half the cost of a TRD midget engine. Pistons, rods, even the turbo, are available for purchase from most Honda service shops. “It’s the same motor your grandma uses to get groceries,” he quips.

So why isn’t everyone raiding junkyards in hopes of builded a boosted Honda mill? For starters, turbocharging hasn’t been approved by a majority of midget sanctioning bodies. Were they to open that wastegate, as it were, officials would need to add a step in the inspection process for checking the turbo and its blow-off valve. Also, the Honda engine is heavier than its competitors; the dual-overhead cams make a top-heavy package and weight is everything in an 1100-pound vehicle, especially if he ever ventures into dirt racing applications. Breidinger is working relentlessly to lighten his engine, though, while moving it down and farther back for better weight distribution.

Come 2021, Breidinger will have two turbo’d midgets, ready for his daughters to run. He’d like to see his little innovation take hold. “I don’t mind sharing what I learned, I just want to go race.” And if bit of disparity in the grid shakes things up, so much the better.