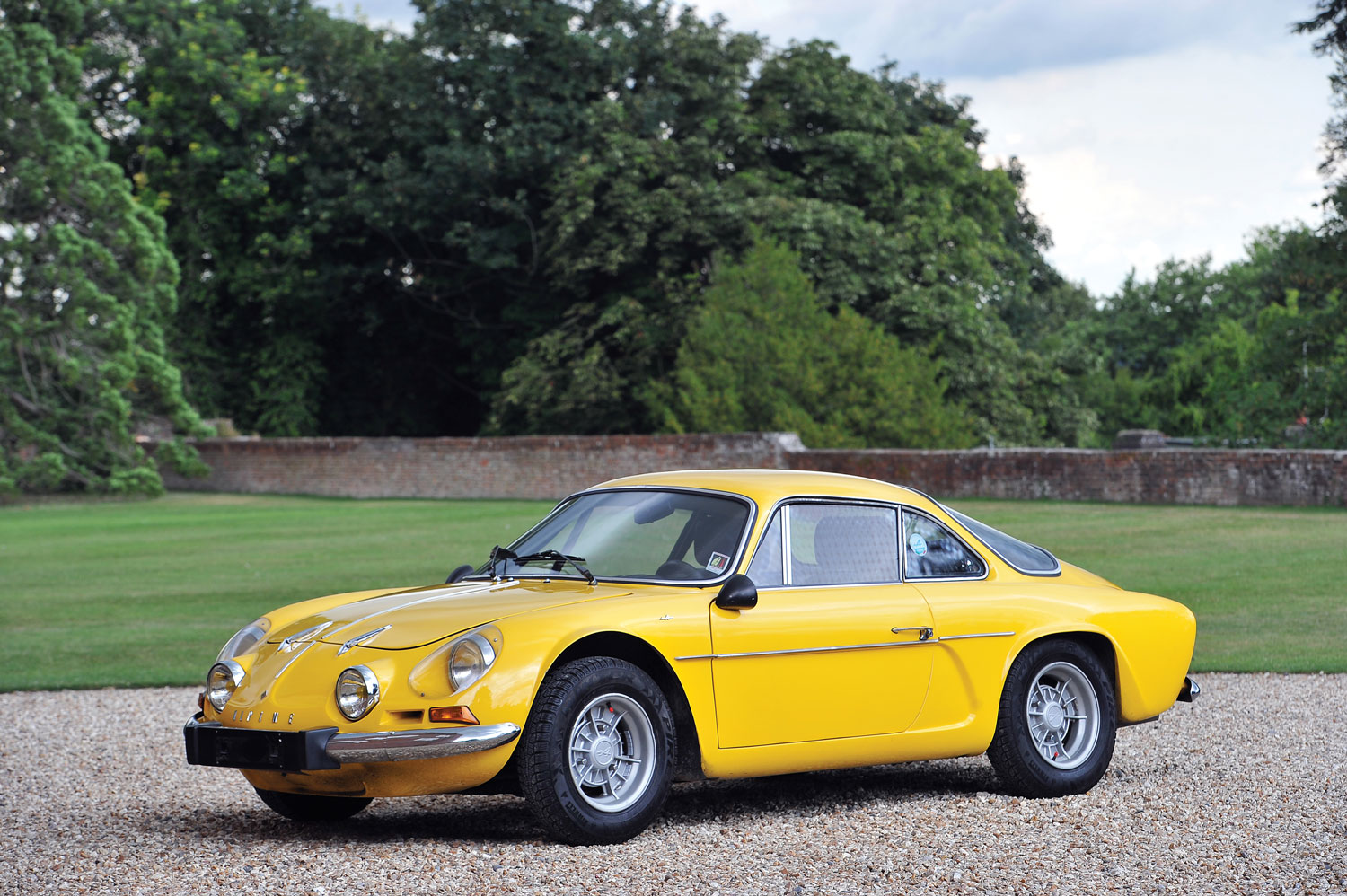

The 1961–77 Alpine A110 packs a rally pedigree and French charisma

Low weight, engine in the rear, snappy handling, enviable racing pedigree, loyal fanbase … It sounds like we’re getting ready to talk about Porsches, but we’re not. Think something smaller, lighter, and more French. The Alpine A110, built by a little company in Normandy, has all those ingredients. It was a World Rally Champion (the first, in fact) and enjoyed a production run of over a decade and a half, during which it got ever-quicker and Alpine evolved into Renault’s performance and motorsport partner. Despite relying on the Renault parts bin, the A110’s design was ahead of its time, and its looks are beyond good thanks to Italian pen-for-hire Giovanni Michelotti, the man responsible for several of Vignale’s bodies for Ferrari and nearly every Triumph from the TR4 to the Stag.

Classic A110s are both hard to find and expensive to buy, especially for a tiny four-cylinder car, but they also offer a ton of rarity, history, pedigree and charisma per dollar.

The roots of Société Anonyme des Automobiles Alpine (pronounced Al-peen for all you non-French speakers) trace back to the early ’50s, with a garage owner and Renault dealer in Dieppe by the name of Jean Rédélé. He started out racing and rallying early in the 1950s, relying—as did so many in postwar France—on the humble, cheap, rear-engine Renault 4CV. While he had modest results running in the Mille Miglia and at Le Mans, his first big success came in the Coupe des Alpes, also known as the Alpine Rally—hence, the name Rédélé chose once he started building his own cars in 1955.

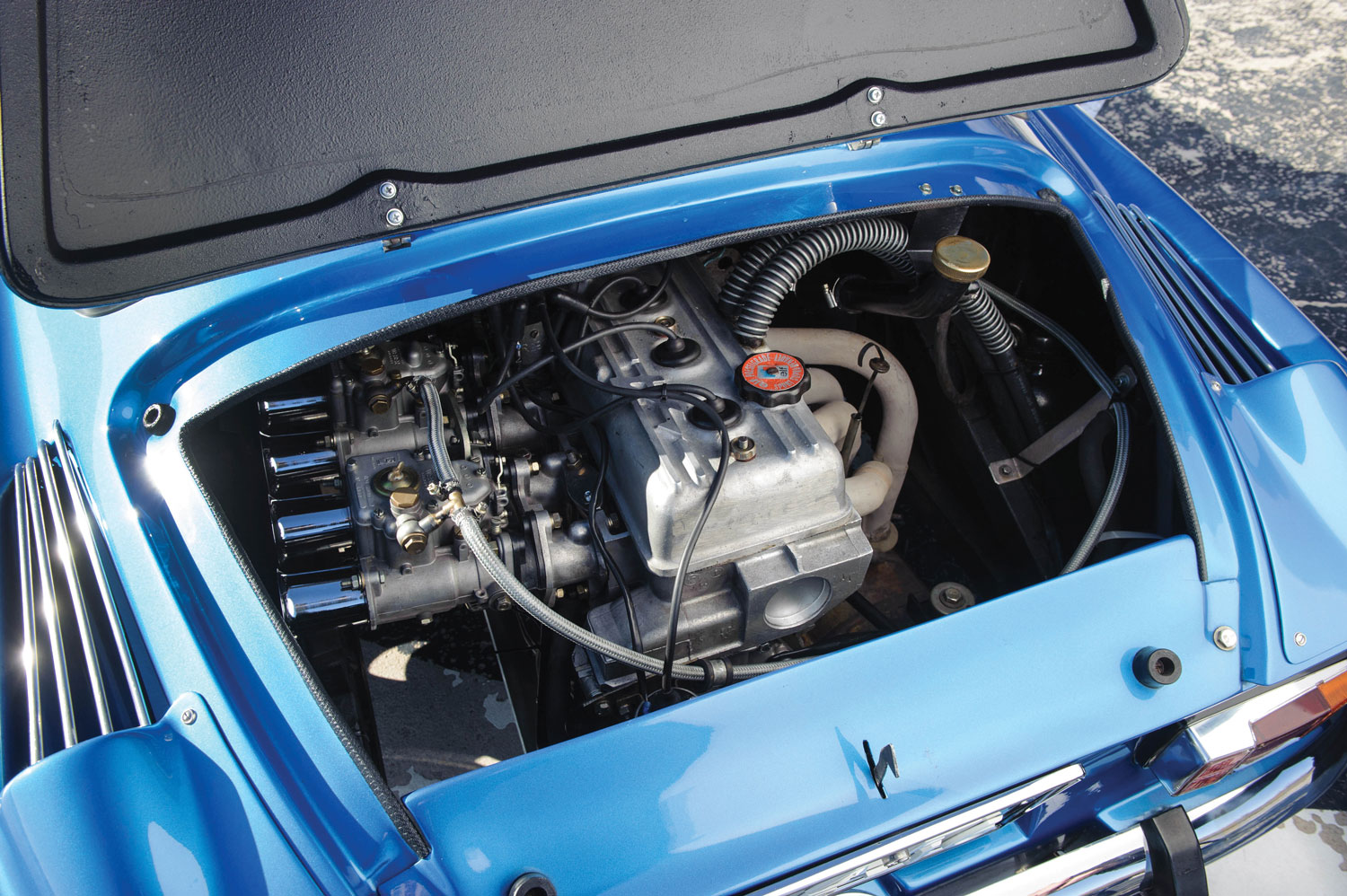

Alpine’s first production car was the A106. While still based on basic Renault 4CV mechanicals, the A106 used a lightweight, fiberglass body shell. This was back when fiberglass was truly exotic stuff in the car world, and little-known in Europe. The more sophisticated Alpine A108 followed in 1960. Underneath its smoothed-out body (still done in fiberglass) was now a steel backbone chassis—not unlike a Lotus Elan’s—and updated mechanicals from the Renault Dauphine. The engine sitting behind the rear axle was the Gordini-tuned version of the Dauphine engine, in either 845-cc or 904-cc displacement.

The A108’s basic design evolved into the A110 in 1961, which used an engine and other bits from the boxy Renault R8. The five-speed gearbox, disc brakes, and rigid chassis added up to a solid platform, and the A110 put Alpine on the map. The car’s first big win was at the 1963 Rallye des Lions, a race that proved both its mettle as a rally contender; its tendency to oversteer (thanks to a 60-percent rear weight bias) and sail around corners in a controlled slide made the A110 a fan-favorite.

The four-cylinder’s displacement (and power) quickly increased from 956 cc to 1100, 1300, and 1500 cc. Later cars were the fastest and used an aluminum, 1600-cc engine. The last competition-spec A110s used an 1800-cc iteration. Small engines, then—but this is a small car, approximately 44 inches tall and about as heavy as a Mini. It’s a nimble little beast.

Alpine-Renault won the French Rally Championship title in 1968 and 1969 and, in 1970, the European Rally Championship. In the International Championship for Manufacturers, the precursor to the World Rally Championship (WRC), Alpine-Renault finished second to Porsche in 1970 but dominated the series in 1971, winning half the year’s events with the 1600-cc A110 and embarrassing the new Porsche 914/6 GT at the Monte Carlo Rally.

The first official year for the World Rally Championship was 1973, and Alpine-Renault took the first WRC title with six wins out of the 13 rallies held, including Monte Carlo. Remember: The car’s basic design was already a decade old. The same year, and in the middle of an energy crisis that hit the sports car market hard, Renault bought a 55-percent stake in Alpine.

Back in the rally world, it was only a matter of time before a fresher car came about and knocked the Alpine off its throne. That car was the Lancia Stratos, the first car designed from scratch with international rallying in mind, which was homologated for the 1974 season. While the Alpine remained competitive on certain stages for several more years thanks to increased displacement and fuel injection, it was no longer top dog. Production of the A110 finally ended after 1977. Alpine soldiered on with the A310—more modern, sure, but nowhere near as pretty—and in 1978 Alpine helped win Le Mans for the home team with the Renault Alpine A442B. Alpine kept building road cars until 1995, but Renault relaunched the brand in 2017 with a new retro-look A110. You can buy one in Europe and it’s a nifty alternative to something like a Porsche Cayman, but it doesn’t live up to the original rally star.

Sources vary on the exact number of classic A110s built, but it’s likely somewhere near the 10,000 mark; regardless, Alpine really didn’t make very many of these little rally weapons. And one of the most interesting things about A110s is that Alpine didn’t even build all of them in-house. As demand for A110s grew along with their list of rally wins, the little carmaker in Dieppe contracted out construction to companies in Spain, Brazil, Mexico, and even Bulgaria.

Back in the 1950s, Alpine entered into an agreement with Willys-Overland’s operation in Brazil to build the old A108, rebranded as the Willys Interlagos. A few hundred A110s were later built in Brazil as well, each branded the Renault Interlagos. In Mexico, meanwhile, a company called Diesel Nacional (DINA), which already had contracts with Renault for truck manufacturing, assembled a few hundred A110s and called them Dinalpins. Another company in Bulgaria (ETO) also built a handful of A110s and marketed them as Bulgaralpines. Most of the foreign-built A110s (about 1500) came from FASA-Renault in Spain.

Aside from some badging and minor cosmetic differences, these contract-built A110s are basically identical to the French-built cars—aside from the fact that they were screwed together by people outside France. Despite being rarer, they always command lower prices than the home-grown versions—they always will. It makes them a tempting value for someone who wants an A110 for fun and enjoys an incongruous “hecho en Mexico” sticker.

With so many different engines, conditions, racing resumes, and even countries of origin, there isn’t one single market or price point for A110s. But they don’t come cheaply. Even a lightly used condition #3 (good) Dinalpin sold in Scottsdale this year for $62,720, while a Spanish-built A110 in the same condition sold in Monterey two years ago for $82,880. They only get more expensive from there, and more of them are in Europe, so a search for a good A110 will likely take you there.

Later, hotter rally-spec cars in particular—especially ones with wins under their belts—have stretched easily into six-figure territory. A Group IV-spec A110 1600S, for example, sold in Monterey last year for $190,400. The most ever paid publicly for an A110 was €369,520 (about $418,500) for an ex-works, Portugal Rally-winning car in Paris last year.

You don’t need a rally winner to have fun, though. Even an early 1100-cc car will be a hoot to drive and great to look at, and you’ll hardly ever see another one. You’ll also have to order parts from the other side of the pond, but that’s just part of the charm of owning quirky foreign sports cars.