Can this Ford 427 “Cammer” make 2000 hp?

It’s been said a thousand times before, but we will say it again: Engines are just air pumps. The more air and fuel you put in, the more power you get out. Of course, anyone who has played with engines long enough knows there is a point of diminishing returns on the vast majority of engine designs. Rarely, however, do we get a first-hand look at the exact constraints.

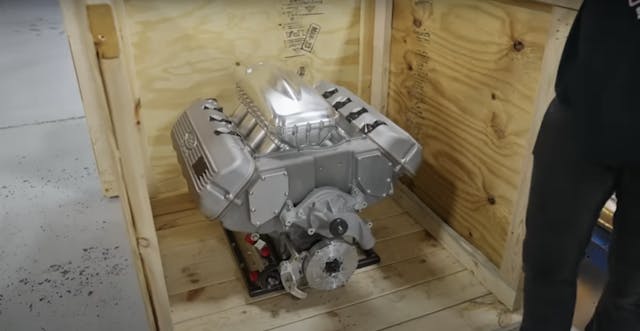

Luckily Steve Morris, a noted race-engine builder, isn’t afraid to identify the problems that keep a Ford SOHC 427—one of the hero engines of the 1960s—from making the kind of horsepower we see in today’s high-output powerplants.

The single overhead-cam 427 is one of Ford’s most famous engines, for good reason. Known as the “cammer,” this V-8 was born as a rival to the venerable Chrysler 426 Hemi, which was dominating NASCAR ovals. However, NASCAR didn’t like that manufacturers were building engines that diverged further and further from the ones in street cars, and for 1965, organizers added a provision to the rulebook regarding “special racing engines.” Chrysler sat out the season in protest. Ford, whose SOHC 427 was no longer eligible, pivoted and used the 427 Wedge, which it had been running for a couple years.

The legend of the cammer lived on, thanks to racers in other disciplines who saw its potential. Drag racers embraced the SOHC 427 despite its nearly six-foot-long timing chain, a feature that gives the engine much of its unique character. Another contributing factor: The camshafts, which rotate in the same direction. Their profiles are mirrored side to side, based on how the valves are situated relative to the cam. That orientation is something that causes Steve Morris a lot of headaches as he chases four-figure horsepower.

The geometry of the valvetrain is stuck in the 1960s for sure. Each of the rocker arms has a roller on one side that rides on the camshaft and a pivoting adjustor cap that engages the valve stem. Each arm also contains an oil passage, which will not allow oil to flow if the adjustor is at too much of an angle. Keeping components from over-extending themselves is critical to keep everything slippery. As Steve points out, the oil passages could be reengineered, but that would require a lot of time. Few people are willing to pay for that kind of intricate development in a one-off engine.

The solution is to dial in the length of the valve stem, even after modifying the rocker arms with larger follower wheels. The amount of lift planned for the camshaft has set this whole problem in motion, but that airflow is critical to making the horsepower Steve’s customer desires. He is just lucky that the short-block is more or less the same as other FE engine blocks, without the provisions for lifters. New castings are available, but that doesn’t mean it’s as simple as bolting things together. Steve estimates he must spend over 100 hours mocking up this particular engine before he can begin final assembly. Even at time-lapse speed, the intricacy of the project is obvious.

Overall, this video provides a fascinating look into exactly what it takes to make unique high-performance engines. This engine even got mounted on the dynamometer—before the customer decided they wanted to take the engine home and either take a break or finish the project themselves. Will this SOHC 427 make the big power numbers everyone hopes? We may never know, but we have a new appreciation for just how tough it is to even try.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

With enough money yes.

I was going to say the same thing. How big is your wallet is the only issue here.

First time I saw/heard one of these engines in a ‘street’ car was back in the early 90’s. I remember the bright orange ’61 Ford Starliner in Milan Michigan at what I think was called the Super Ford Nats. The magazine Super Ford was huge at the time. Funny enough, my car ended up in that magazine a few years later, lol.

That Starliner certainly left an impression and to just hear it sit there and idle was awesome. The long timing chain certainly adds to the wonderful mechanical sounds this beast produces. It may be antiquated but for the time, it worked.

Deep pockets hit their limit too at some point. The pursuit of big street power costs big money. With the purchase of the engine and the subsequent work, he’s likely spent spent close to what a Sonny’s 1005 cube terror would cost.

I don’t have to worry about it though, neither of these are anywhere in my budget reach, ha!

It does seem that the owner that commissioned this build bought a very expensive piece of garage art…

Some folks are willing to do anything to keep the past alive…For the horsepower, there are much less expensive and simpler ways to get crazy. Toughened LS with a large turbo, or two – for example.

“NASCAR didn’t like that manufacturers were building engines that diverged further and further from the ones in street cars…” This was back before NASCAR became the automotive equivalent of IROC/WWE. I doubt that there is a single production car part on today’s “stock” cars, and the series is the worse for it.

Since there are no factory cams or cores available to base from (and no specs?) it seems to me these new ones have too small a base circle, so the larger follower rollers are a clever workaround….I think the customer ran out of money or patience. Although usually when you say you can’t wait any longer and you’re picking up your job incomplete, that job goes to the top of the priority list. Fascinating stuff!

They were making more than 2K HP back in the 60’s. Mickey Thompson’s 1969 blue Mach 1 which dominated

the Funny Car class is only one of many examples how that motor did in competition. Ohio George Montgomery, Dyno Don Nicholson, Connie Kalitta are just a few who ran the 427sohc motor and dominated.

I’ll admit I am skeptical of big horsepower claims made from that time period. If a 427 Cammer was making 2k horsepower in the ’60s it was likely a big blower and nitromethane-fueled combination that lived in short sprints with significant tuning and maintenance between. The fuel and usability constraints are something that needs to be considered.