When Porsche asked if a car could live forever

Porsche proudly points out that about 70 percent of the cars it has built are still on the road.

Desirability, strong resale value, and the support that the company offers for its classic models undoubtedly play a role in keeping vintage 911s, 968s, and 944s out of junkyards. That 70-percent figure, however, is also a testament to the time and effort the company’s engineers have long put into designing relatively solid cars. One of Porsche’s earliest longevity-related studies is the Forschungsprojekt Langzeit-Auto concept unveiled in 1973.

The car’s name, often abbreviated as FLA, roughly translates to “research project long-term car.”

Car-bashing—a popular pastime in Europe—is not a recent invention. “Boos have joined the joyful car chorus since the early 1970s,” a 1973 Porsche press release said, “and there is no lack of voices to damn the automobile with an existence and future of the drabbest kind. Many such complaints are so emotional they cannot be taken seriously. Others, however, give us sufficient reason to further consider the situation of the automobile and its possible future development.”

Porsche wisely ignored its more radical critics, but with the FLA, it gave the moderate ones something to chew on. The concept, Stuttgart claimed, was capable of lasting for 20 years or 300,000 kilometers (about 186,500 miles), remarkable figures at a time when five-digit odometers were common. (For context, documents in Porsche’s archive peg the average cradle-to-grave lifespan of a 1970s German car at about 10 years.)

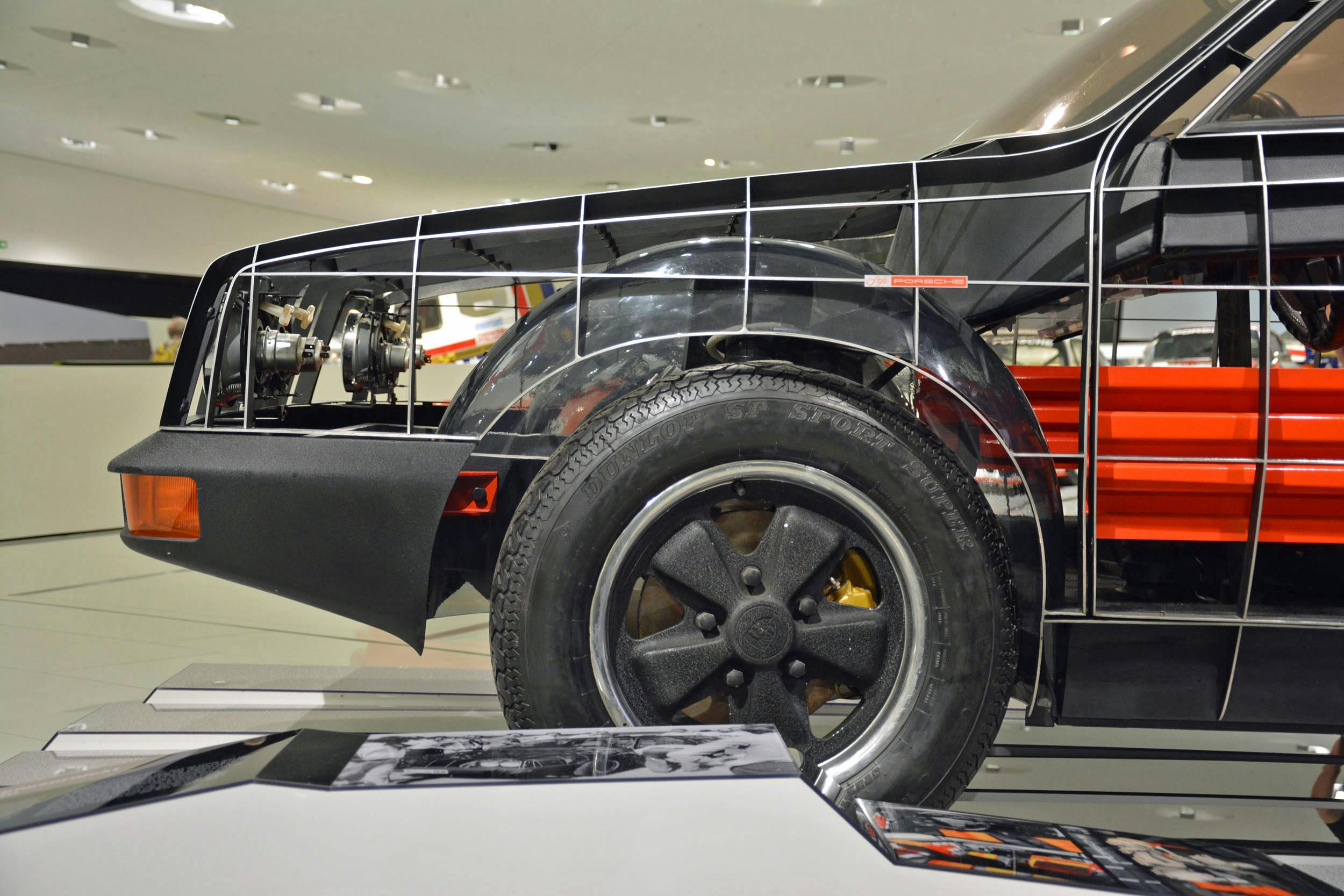

Commissioned by Germany’s Ministry for Research and Development, the FLA prototype made its public debut at the 1973 Frankfurt auto show. It must have turned quite a few heads—the shape of a city car, with a gridlike and see-through false body seemingly made from giant egg crates.

Enthusiasts, Porsche said at the time, could rest assured: Mass-production was not the project’s goal.

“[We] put this long-life study up for discussion at [Frankfurt] in the hope of animating drivers as much as car producers,” the company’s PR department explained at the time. “Incidentally, the long-life automobile on display doesn’t pretend to be a specific car, but rather a demonstration intentionally kept independent of any specific design principle as an idea, neither complete nor final.” The FLA, it added, was designed as a “lower-middle-class car.”

In that light, the design’s virtual anonymity makes sense—only a set of 15-inch Fuchs wheels, similar to those used on the 911, and small “Style Porsche” emblems on the fenders identified the FLA as a product of Porsche’s R&D department. Wheels and badge aside, the car could have been just about anything else. (I think it’s vaguely Volkswagen Brasilia-esque, but maybe that’s just me.)

While the display car offered little in the way of bodywork, a production model, Porsche suggested, could feature aluminum and stainless-steel components in order to minimize corrosion. Significant use of plastics and other synthetic materials would allow much of the car to be recycled at the end of its life.

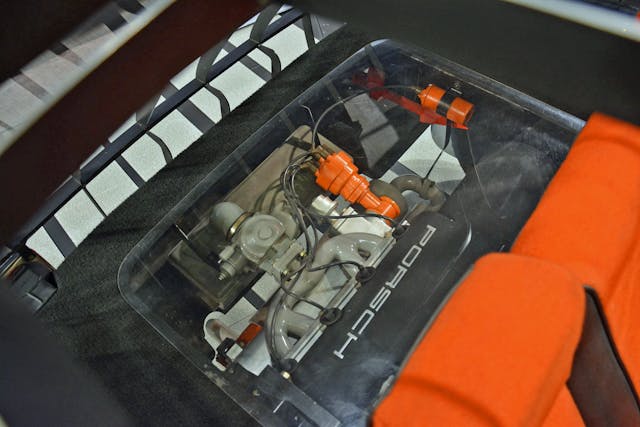

Undoubtedly to the chagrin of its racing-obsessed engineers, Porsche learned that designing a car to last 20 years and 300,000 kilometers required the use of a “wholly unsporting engine.” Instead of an air-cooled flat-six, as in the 911, the FLA featured a water-cooled, 2.5-liter four-cylinder tuned for 75 hp at 3,600 rpm and a 4000-rpm redline. Even in the 1970s, that wasn’t asking a lot of 2.5 liters; Porsche’s 924, released in 1976, offered a 2.0-liter four rated for 123 hp.

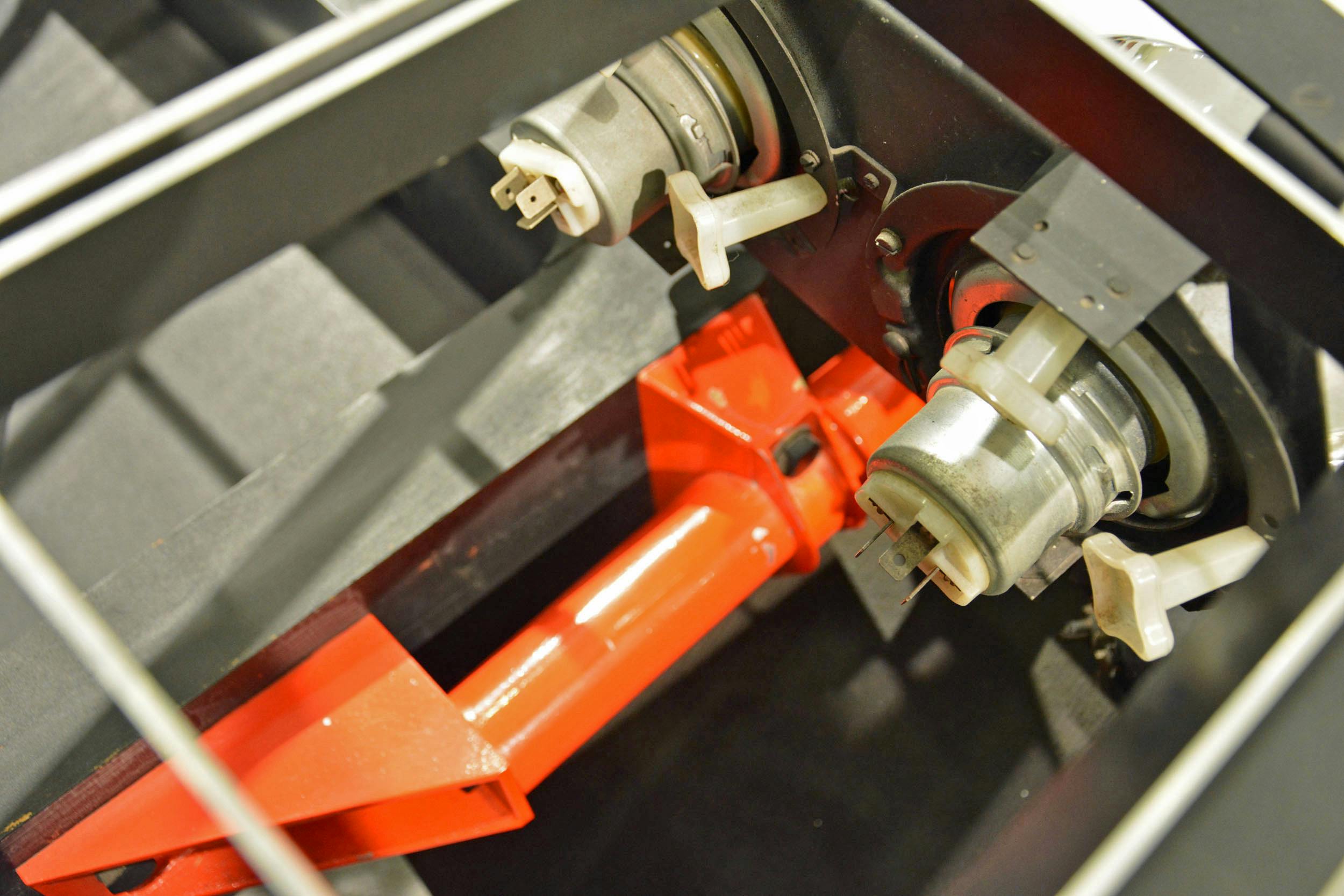

The FLA’s engine was rear-mounted, spinning the rear wheels via a three-speed semi-automatic transmission. Combined with the car’s predicted gearing and drag, this would be enough, Porsche predicted, to send the 2200-pound concept (if fitted with full bodywork) to a top speed of 99 mph. Some of the measures taken to increase longevity included oversized engine bearings and transmission gears, for reduced stress and wear, plus an electronic ignition and a corrosion-resistant exhaust.

All told, the company predicted that a car designed to last 20 years would cost about 30 percent more than a comparable model of the time. It would also cost about 15 percent less to operate and maintain, Stuttgart suggested, noting that this number could increase if shortages and price hikes wreaked havoc on car production—an eerily prescient forecast at a time when oil embargoes and chip shortages were still the stuff of science fiction.

Porsche’s research wasn’t limited to the oily bits. The manufacturer went so far as to detail a new business structure for carmaking, one that included “special overhaul plants” where cars could be refurbished or modernized where appropriate, refitted for another 20 years of service. Manufacturers in the aviation and marine industries were already doing this sort of thing at the time, and the process is arguably what Singer Vehicle Design does today with classic Porsches.

The 1970s were a tumultuous time for the automotive industry, and Porsche’s competition had greater problems to solve than longevity. The conversation that the firm hoped to start didn’t really happen, at least not at the global stage. For its part, Porsche stressed, there was no space for the FLA in the company’s catalog: “[We] certainly have no intention of producing such a long-life automobile in the near future.” That said, rust-resistant hot-dip galvanized body panels appeared on the 911 in 1975.

Porsche frequently compared the FLA to the various Experimental Safety Vehicles (ESV) prototypes that emerged from various government- and carmaker-funded projects in the 1970s. Those vehicles displayed a varying degree of visual and engineering wildness: English sports-car manufacturer MG notably tried to drunk-driver-proof a heavily-modified MGB GT, for example. As Popular Mechanics said in 1972, “The world may never want to place an ESV in production, but we sure want the answers they can give us.”

We wouldn’t want to commute in the FLA, but the car deserves credit—the thinking behind it is undoubtedly at least a small part of what keeps now-classic 911s on the road.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Pre crossover era, Porsches were trophy cars. Some destroyed through abuse, a few through normal attrition and most kept as prize art. There are no masses of Citations and 4-door Galaxies to up the loss count.

The logic of longer lasting a refurbishing is sound. reduce-REUSE-recycle after all. Last I heard stats U.S. auto fleet was approaching 12 years for average age (pre pandemic). Volvo’s study (2022?) said their EV was good for 10 years. –we haven’t made gains here, because there is no will or profit in doing so.

Governments are surely showing us will in EV adoption. But that’s reduce-reuse-recycle-REPLACE which has a huge short-term cost. Assuming EV tech improves (and electric grid, etc.) then yes in the end the math maybe works out.

Math could work out a lot better if the money was spent on reuse… and the will was put towards longer lasting.

Porsche concept looks like an AMC to me.

When German engineers estimated the average life of a 1970s German car at 10 years, they hadn’t sampled their own products, or those of Mercedes, BMW or even VW. Speaking as a guy with a 50+ year old daily driver BMW 2002–and having seen equally long-lived cars from other German manufacturers of that time, their only weakness was tinworm depredations. Now American cars of that era…even the expensive ones simply didn’t have the build quality that their German counterparts displayed. Compare similarly priced Pintos and Vegas with a VW Beetle, or a Buick with a BMW Bavaria, or a Cadillac with a 300 (or 600) series Mercedes…

Honestly I’m so glad that Porsche never made this car lmaoooo

Like it looks nothing like a Porsche at least with cars like the Panamera, Macan, and Cayenne they’re recognizable as Porsche cars and it’s not just the badge it’s how well the design language has been implemented even if they’re not the 911, Cayman, or Boxster at least Porsche knows how to get things right

186K miles was probably unusual in the ’70s, although substantial numbers of slant six Chrysler products went well beyond that, probably often without being refurbished. There are fair numbers of cars today with double that mileage or more, just from better parts and manufacturing. And even back in the ’60s, and probably earlier, Volvos were built to amazing standards. I once met a guy who’d drive a P544 to half million miles. The salt on Massachusetts roads killed that car after over 30 years.

Car will last. They have to be taken care of. My 96 Cadillac runs great, just needs some bodywork from the teen years. My 15 Chevy Silverado isn’t old but has 265k miles, got there with great care. my 97 Camaro has 112k but runs like a top and is in great shape. Had to rescue it a little from its years with my teen brother but it will go another 25 easy. Anyone who has seen the YouTube Channel Just Rolled In know why cars don’t last. It’s usually the loose nut behind the steering wheel and in the driver’s seat.

How about incentives to the owners who keep old cars going? That’s a much more direct incentive, and in many cases would go right where the incentive would do the most good. Encase the plan in some sensible safety and emissions wrappers, and bob’s yer uncle.

If we really wanted to reduce carbon then our cars would last 2X or 3X and incentives would be given to encourage manufacturers to develop better, long living cars. This would result in less energy to produce and much less waste.

the guys at AMC must have admired this cars look, AMC Pacer anyone?

The Pacer and the 928 have a lot in common.

I was thinking AMC Pacer also. This is not a compliment.

I was thinking more like a Gremlin. Compliments to AMC… Did Porsche make inline fours back then? Was it their first one and no one realized the “E” wouldn’t fit on the valve cover?

Interesting. I am guessing – hoping, actually – that these photos were taken some time ago. I was at the museum on Friday (14 Apr) and didn’t see this; either it is no longer on display (good) or I missed something (bad).

Why wouldn’t you want to commute in it? Looks and sounds exactly what it would be for. Not exciting, but good mileage and reasonable comfort for a commute.

There was a California study 20-30 years back the basically said the best way to recycle a car was as a car. In other words, to refurbish it. Costs more to strip/crush/recycle the individual components than to rebuild the body and drivetrain and replace wear parts like interior fabrics. The problem with that is economics. Some friends and I did a paper “study” on what it would cost to refurbish a car. We choose a Ford Taurus (this was the 90s) because it was popular enough and had been in production looking about the same for 4-5 years at the time. None of use were really auto professionals, but all had at least some experience in refurbishing/restoring/modifying older cars, and a couple people had experience with small scale manufacturing. Allowing for some error, we determined that a company could sale a refurbished (with new wear items, rebuilt drivetrain, repaired as needed and freshly painted body) Taurus for about the price of a new Fusion. Not a lot of savings to the customer. Basically you got a full size car for a mid size price. If such a venture was successful used car prices of the model being refurbished would go up and you’d have to go increasingly further to get them, though a trade-in program would help some. We assumed a ground-up deal — a facility would have to be obtained and all necessary machinery, but some larger items like rebuilt engines and trannys coming from an outside source already capable of larger scale rebuilding (like maybe Jasper for engines and trannys). Basic disassembly and assembly done in house.

Now if an existing manufacturer were to take one of their under used/disused facilities and started doing something like this, maybe start with pick-up trucks since there is a higher profit margin and new prices are through the roof, it could be done at a better price point and should be profitable. But for a new ground floor startup it would be tough, and a hard sell to financiers. That’s why you only see things like this with very popular and usually pricey vehicles, and at a relatively small scale.

There was a truck sold in the late 50s using used parts — the 1955-1957 Powell “Sport Wagon” pickups and station wagons. Approximately 1,200 pickup trucks, 300 station wagons were built and sold using modified 1941 Plymouth chassis (including drivetrain) recycled from junkyards. These parts were long out of production but lay in abundance in scrap form throughout the salvage yards of Southern California. A decent chassis could be had for just $45, with an L-head engine and 3-speed gearbox for not much more. Powell representatives would scout and collect the pieces, and send then off to be refurbished and rebuilt by an outside supplier in Glendale. Powell text copied from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Powell_Manufacturing_Company and https://www.makesthatdidntmakeit.com/powell.

…I know this is off topic, but what about the valve cover photo that says “PORSCH”?

Hmmm… My ’66 Mustang has 183k miles on the original (untouched) 289-2 barrel carb and its C4 auto didn’t need a rebuild until 163k miles. Who knew Lee Iacocca’s engineers, working in the 60’s with a platform based on a late-50’s Robert McNamara design, could give those 1970’s Porsche boys a run for their money?

Wow! That thing looks like an AMC Pacer… UGH!