A Jaw-Dropping Tour of Speedway Motors’ Museum of American Speed

Unless you live there, or you have family or friends in the area, why would you visit Lincoln, Nebraska? You might visit to see the state capital. Or the University of Nebraska, home of the Cornhuskers. But heading the list of “top things to do in Lincoln” is the Museum of American Speed.

“This is an amazing collection of everything related to early speed development,” one online reviewer enthuses. “There are … vintage racing cars and touring cars and more engines than I ever thought existed … also metal lunch boxes, movie posters, pedal cars, record album covers, hood ornaments, vintage car parts and so much more. This is a Smithsonian-quality collection and exhibit, and each display is artistically created to demonstrate that quality… I highly recommend a visit and if you are a ‘car person,’ it should be on your bucket list.”

Modest Beginnings

“Speedy” Bill Smith was a winning racer, team owner, race car builder, entrepreneur, and a passionate collector of anything and everything about the history of speed in America. In 1952, he and his hard-working wife Joyce founded Speedway Motors to sell automotive and competition parts and accessories in Lincoln. Then, 40 years later, they opened their Museum of American Speed, “dedicated to preserving, interpreting, and displaying physical items significant in racing and automotive history.” As they liked to say, every car in it has a story.

“Our dad started this business right out of college,” said son Clay Smith, when we visited while researching hot rod guru and Autorama show founder Bob Larivee’s latest book. “And my mom loaned him $300 to get it started. She had a good job, so when he had sales, that money could go back into the business. He didn’t have to use it to support the family. In the early days, he raced motorcycles, then roadsters. He was driver, mechanic, painter, truck driver, everything … and he became a better car owner, builder, and fabricator. Bill had a great ability to build and field very competitive cars. It was serious business; he was there to win … [and] he won more than his share.”

Because he was involved in the formation of SEMA (Specialty Equipment Manufacturers Association) and had friends who were manufacturers, Bill Smith was well connected with the entire industry and always knew what was happening elsewhere despite being based in Nebraska. “We were advertising in Speed Mechanics magazine in 1953,” Clay Smith recounted, “and there was a list in that same issue of every speed shop in America, hundreds of them. And the only one that survives today is Speedway Motors.”

The elder Smith was enamored with what early engineers could do. Many were backyard engineers, or “practical” engineers as he called them, who worked at a trade—very bright people but not trained engineers. He wanted to collect their work and believed an object could tell its story better than its creator could, so his original motivation was to preserve that part of history.

“We had a mezzanine in the building,” Smith said, “and Bill’s ‘stuff’ would get parked up there. And we had the good fortune through all those years to be included in the process. With the toys, for example, Bill and Joyce would go to events each year—a toy show in Chicago or Atlantic City—and I would go with them to negotiate buying toys. We also went to all the swap meets with them, displaying as a vendor but really there to acquire ‘stuff.’ His stuff was always stuffed into one of our warehouses, and this museum is its second home.”

The Museum

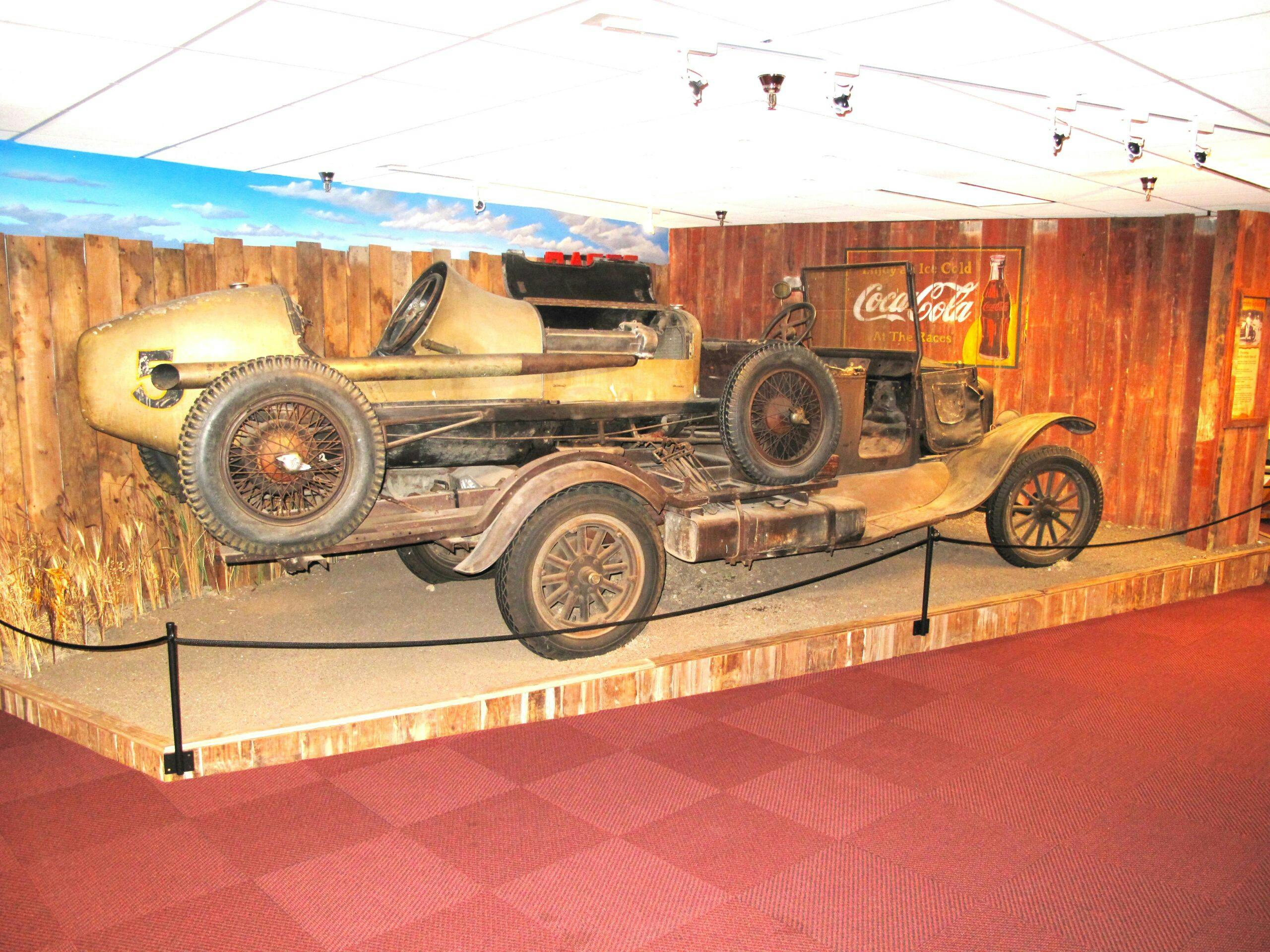

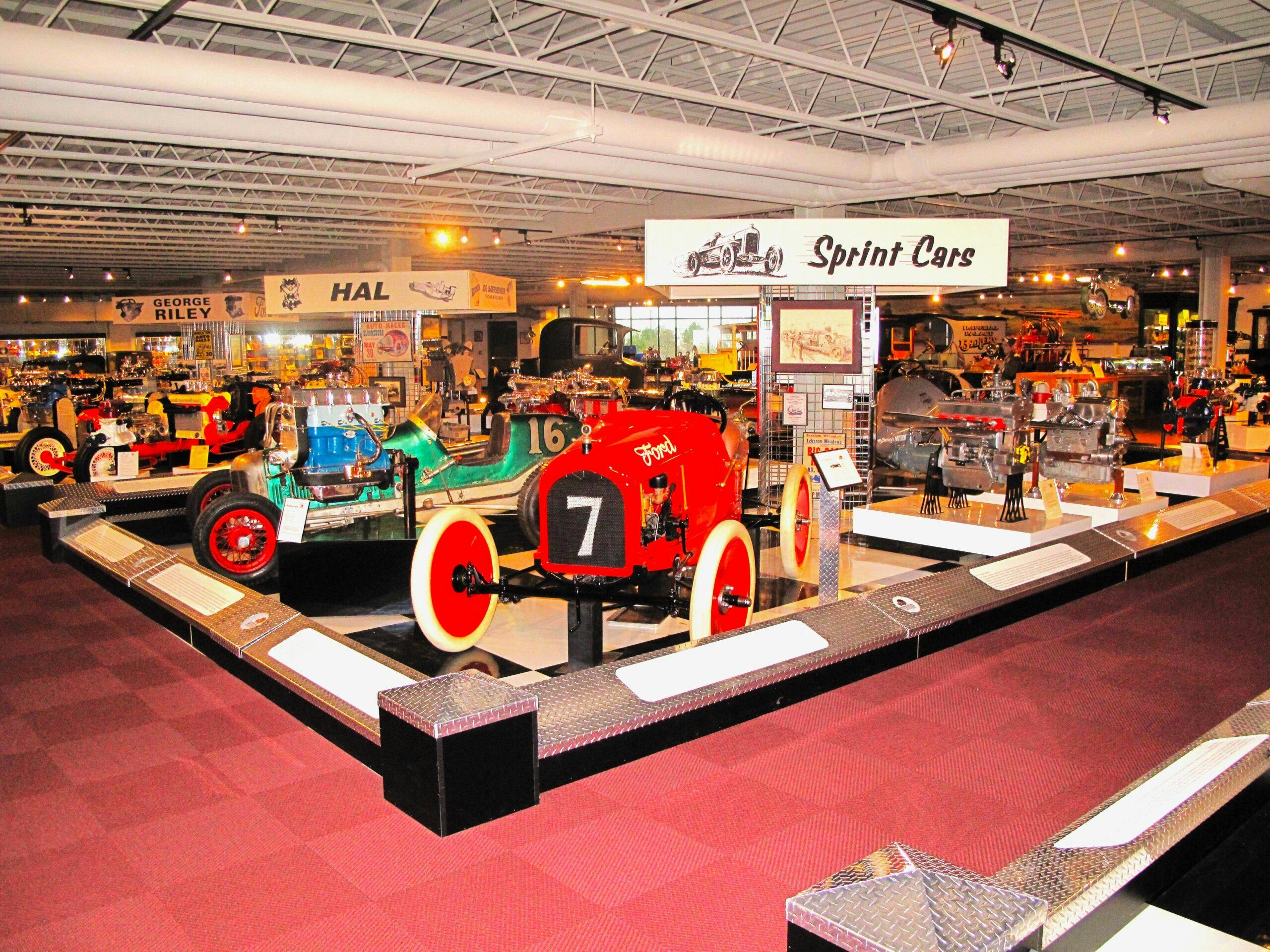

The museum moved to a three-story, 150,000-square-foot building in 2001, across the parking lot from Speedway Motors, and it recently completed a 90,000-square-foot addition to house its rapidly growing displays, which include more than 300 cars and 800 historically significant engines. With over 30 unique gallery spaces, the museum educates visitors about all forms of American racing, including Indy, drag racing, NASCAR, SCCA, land speed, Pikes Peak, sprint car, midget, quarter midget, board-track, go-kart, motorcycle, BMX, and more. It also celebrates the history of hot-rodding, show cars, and historic production cars. The meticulously designed displays and dioramas spread over three floors display these vehicles and other artifacts in settings where viewers can see them as if in their original environments.

It boasts the largest collection of pedal cars on permanent display. The Eric Zausner-EZ Spindizzy Gallery features the most comprehensive collection of gas-powered tether cars. And the Darrell Mayabb Automotive Art Gallery shows an assortment of rare bronzes, auto design studies, and paintings from artists Tom Fritz, Peter Vincent, Stanley Wanlass, and many others. There are also significant displays of rare auto-related movie posters, signed musical instruments, tin toys, lunch boxes, die-cast cars, and space toys—truly something for everyone.

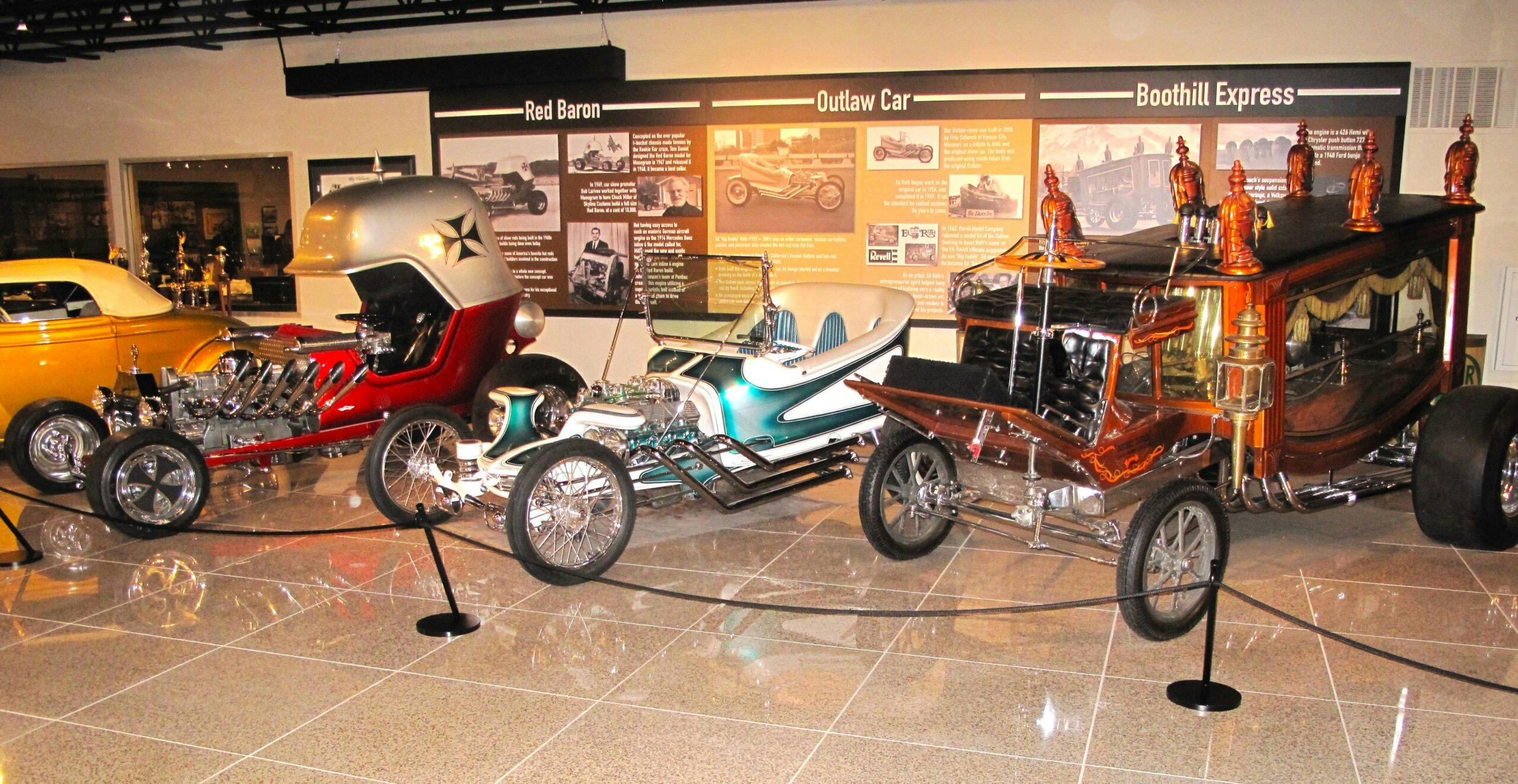

“One of my dad’s first jobs as a kid was working at an En-Ar-Co gas station a block from his house,” Smith relates on our tour. “So we re-created it here. This track roadster was on the cover of Hot Rod with Linda Vaughn. This blue ’32 is one of few cars that has been on Hot Rod’s cover twice, first as a kit that you could buy for $3995, then again after it was completed. We have Bonneville racers here, drag racers there, and NASCAR and show cars over there, including three that we bought from Bob Larivee’s collection. The most iconic one is the ‘Red Baron,’ next to the ‘Outlaw’ and the ‘Boothill Express,’ which is the actual funeral hearse that carried James Gang member Bob Younger, subsequently turned into a drag car by Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth.”

Clay Smith shows us the many “Icons of Speed” dioramas for people who were important in America’s pursuit of speed, including Mickey Thompson, Smokey Yunick, Vic Edelbrock, and Carroll Shelby, who was a good friend. “When Shelby created this Series One car, Bill helped him find engines for it. He had bought a train car full of overhead-cam Oldsmobile Aurora engines for hot rodding, and Shelby used them in the last run of his 249 Series Ones.”

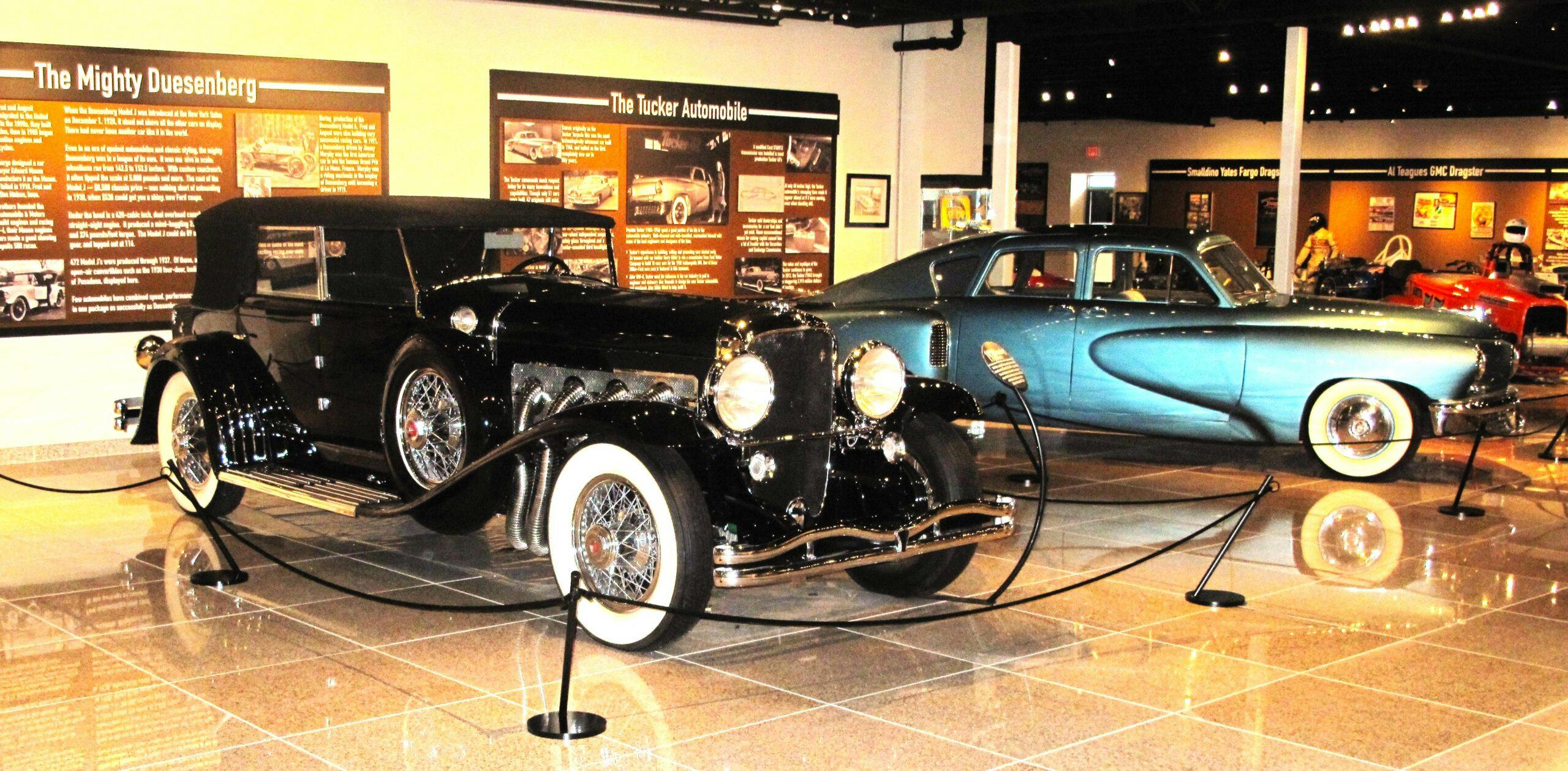

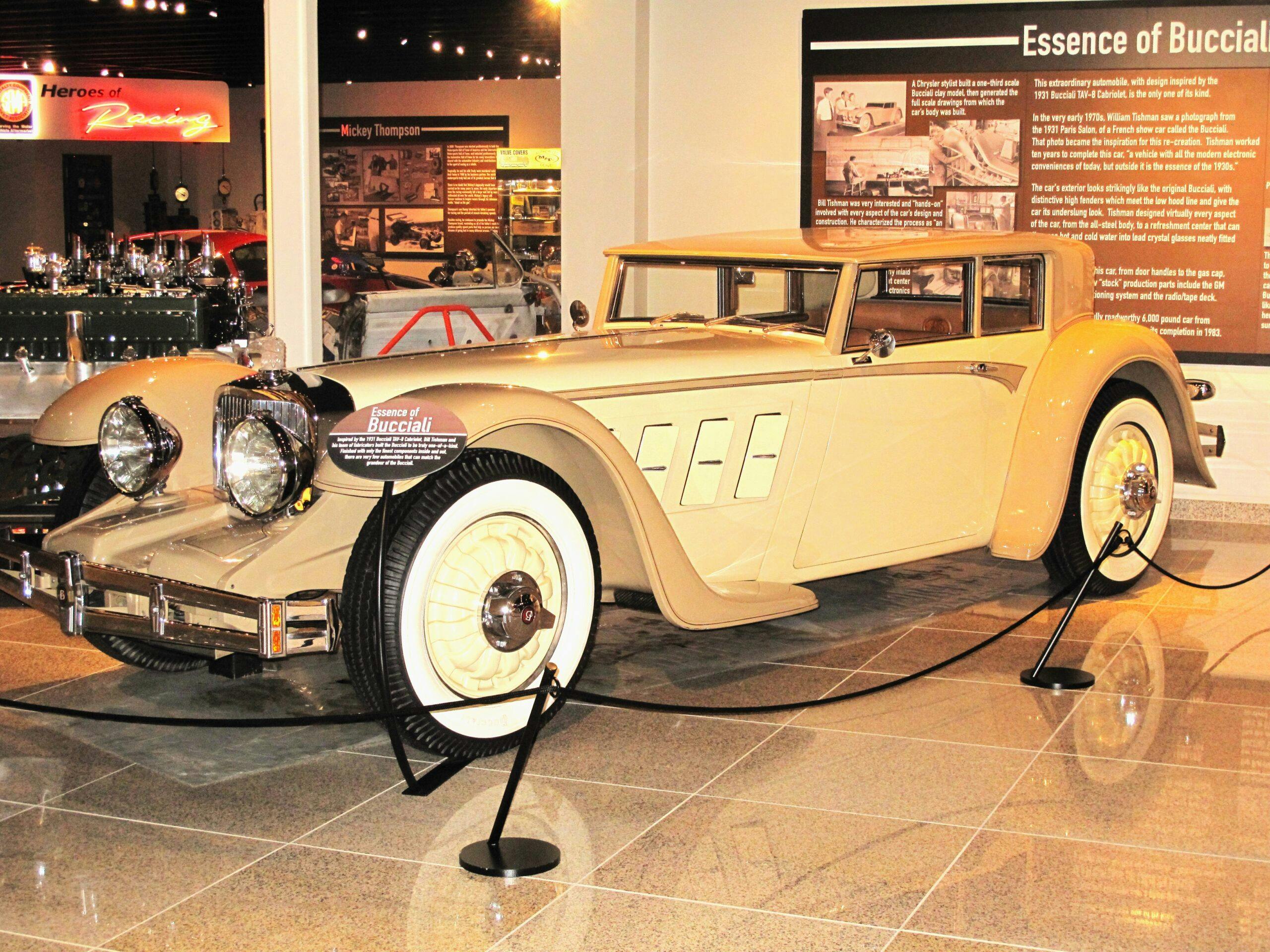

Bill always wanted a Tucker because of its innovation, so there sits one alongside a regal Duesenberg. “The Duesenberg brothers originally were racers,” Smith says, “and this is one of their Model Js from 1930.” Next to that is a hand-built Bucciali. “The original won the Paris salon in 1931, then was destroyed in World War II. William Tishman of Los Angeles went through an arduous 10-year process to re-create it from pictures. My dad had this recreation car in his garage and on Friday nights, he would take it to get ice cream at the drive-through.”

Also on our tour was museum curator Tim Matthews. “This is our Land Speed Record area, with cars from Bonneville and the dry lakes,” he says. “Most of these cars are record-setters in their classes, including Ron Main’s ‘Flat Fire,’ the world’s fastest flathead Ford. This red Speedway Motors car, built by John MacKichan here in Nebraska, set a record at 348 mph for the Small-Block Chevy Streamlined class.”

Smith points to a charred race driver’s suit in a display case: “This is one of our favorite displays. Bill Simpson created fireproof driving suits, and my dad was his first customer. That suit is the one he wore when he set himself on fire in the pits at Indy to prove its quality.”

Second Floor

Up one floor is the Soap Box Derby area, with a variety of creative derby cars and drivers’ helmets through the years. Then comes the Model T room. “Almost everything in here is Ford Model T speed equipment,” Smith says. “My dad was enamored with the Model T era, because that was the beginning of the aftermarket. The Model T was so simple that almost everything on it could be improved, so that created a huge market for accessories to make your Model T run better, faster, cooler, or look distinctive. You could get an accessory body to turn your Model T roadster into an enclosed car, or you could turn a Model T into a snowmobile.”

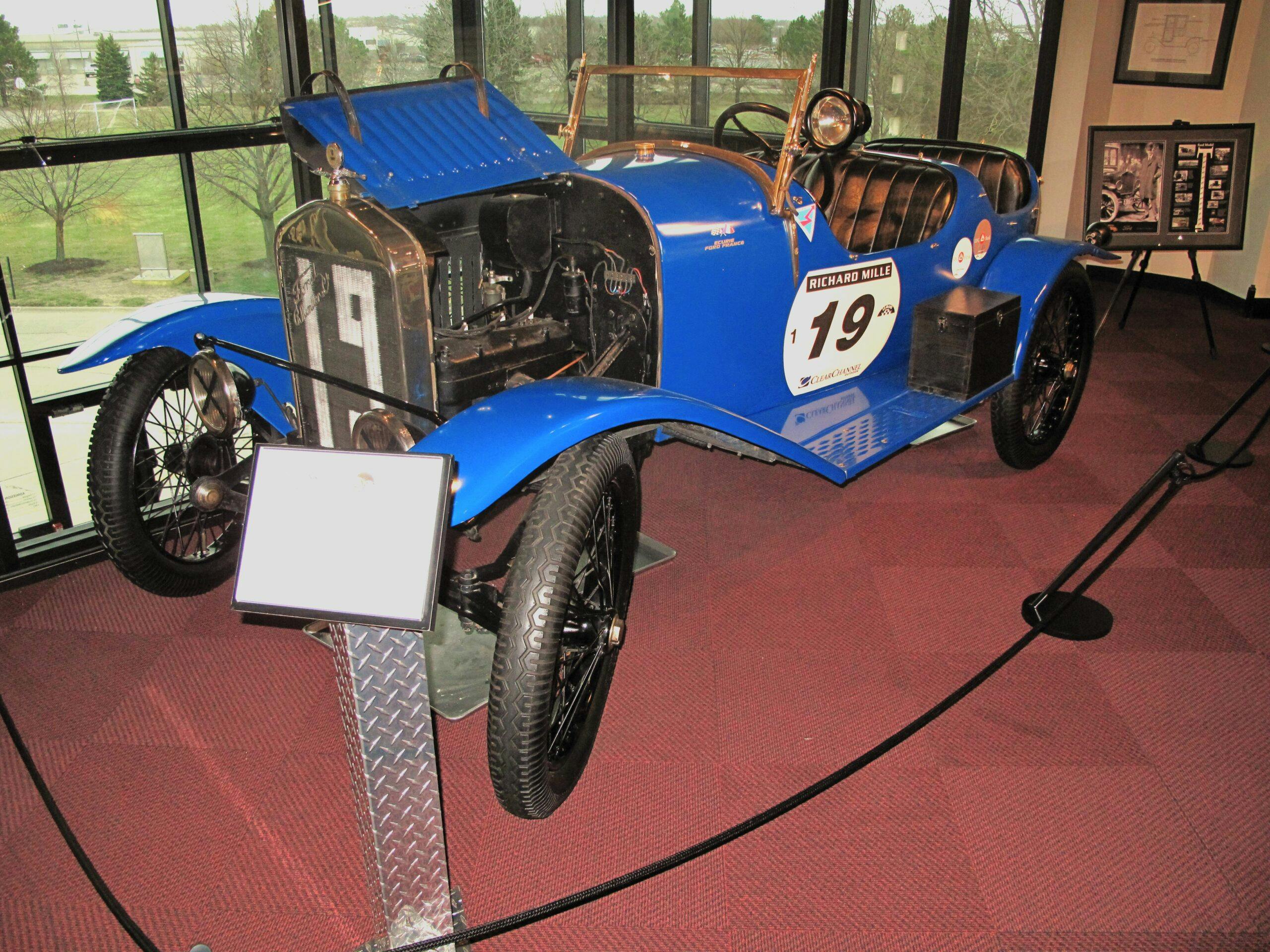

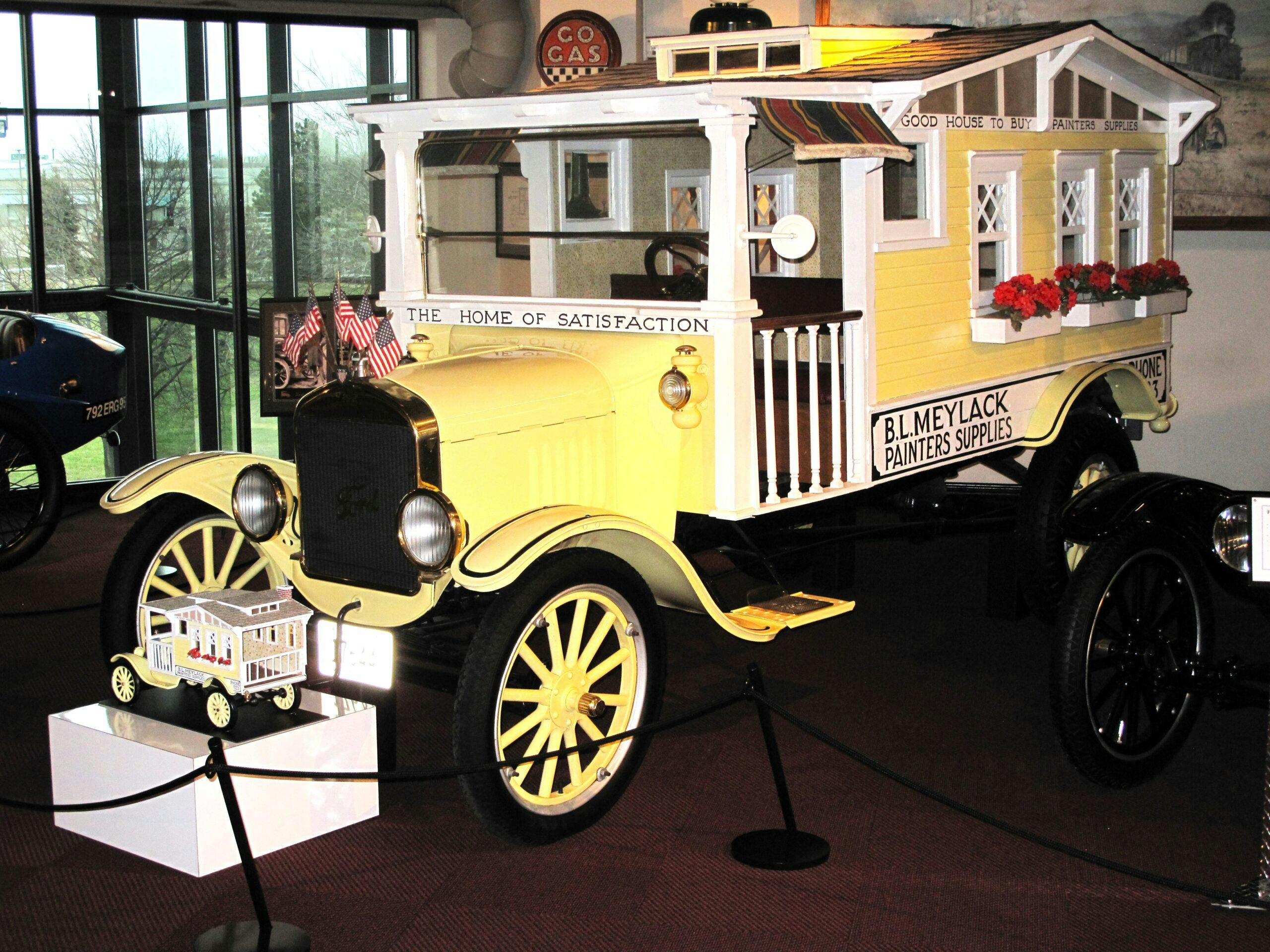

There on display is the only Model T that ever raced at Le Mans, #19 in 1923, plus Model T–based accessory cars made for businesses: a painter’s car, a bakery car, and one that looks like a house. “This is a prototype six-cylinder Model T engine from 1912, which is rare because Ford did not make six-cylinder engines back then,” Smith continues. “This is a double-overhead-cam head for a Model T engine that was built in the teens. This is the five-millionth Model T, which was built in 1921. This is a twin-engine T. This is a special suspension system. We think we have over 5000 accessories made for the Model T.”

Another room shows the evolution of midget race cars and a huge variety of midget racing engines. “They ran everything, including boat and motorcycle engines,” Smith explains, “and this one is a version of an Offenhauser.” In the Model A room are all kinds of speed equipment for, you guessed it, the Ford Model A. “When you think about how few years those cars and that engine were in production,” he says, “the variety of speed equipment made for them was amazing. And here on the wall we have 311 different intake manifolds for flathead Fords.”

Another huge room is chock full of original, unrestored, old pedal cars, probably the world’s largest collection, some said to be more valuable than real cars. And just around the corner are hundreds of examples of probably all the auto-related kids’ lunchboxes ever made.

Third Floor and More

Another level up is what was said to be Joyce Smith’s favorite floor. “She would come up here and tell stories about all the different things,” Smith says. “All the pedal cars up here are restored, good as new. And here is Joyce’s Yellow Cab collection. She had a thing about Yellow Cabs. Over here is Buck Rogers and all of Bill’s childhood toys. The Spindizzy Foundation gallery is devoted to gas-powered tether racers, which zip around in circles on a cable anchored to a pole in the center. Later, they put them on rails on miniature board tracks. These cars date back into the early 1930s, and they’re incredibly complex in the amount of engineering that went into them.” Matthews, the curator, adds that, with recent donations, this is now the largest and most complete collection of Spindizzies available for public viewing in the country, “and we have ambitions to make it even greater!”

Back on the ground floor, we see some special areas with historian Mike Kelly. “This is our Harry Miller room,” he says. “Harry was the godfather of racing in the early days. Though he dropped out of school at 13, he was a great engineer but not a great businessman. He went belly up in 1933, but every car on the Indy 500 starting grid in 1934 had a Miller engine in it. When Miller went bankrupt, Fred Offenhauser bought the tooling and the rights to his four-cylinder engine, and for the next 27 years, Offenhauser engines won 24 of the 27 races. And from 1946 to 1962, Offenhausers won every single IMCA championship race.”

Kelly points out a sprint car that won over 200 races and championships in 1955, ’56, ’57, and ’58. “This Blue Crown car won more championship points than any other single car in history,” he says. “See the ‘Speedway Cocktail’ on this car number 45? Joe Lencki made Speedway Cocktail oil additive in his bathtub, bottled it, and sold it to the other racers. When Joe went to Fred Offenhauser and asked him to build a six-cylinder Offenhauser engine, Fred at first refused, then relented. But Lencki would have to assemble it and call it a Lencki-six, not an Offenhauser. They made just three of those engines, and this is one of them. A second one is in the brown car over there that looks like a Watson roadster.”

Through the years, another Smith son, Carson, got to know a lot of his father’s drivers. “He had some of the very best,” he says. “The business was built around making money for the race team to function and using the race team to promote the business. It was all tied together. His early focus was on racing engines, because racing engines were almost always somebody’s passion, the most important things they worked on, and racing evolves pretty fast.”

The museum’s Indy Galleries have been going through a major expansion. “In 2023, our museum merged with the Unser Racing Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico,” Matthews says. “The Unser family is one of the most storied families in automotive and racing history. We have had racing partnerships with members of the Unser family for over 38 years and are honored to welcome the Unser collection to our museum. We just completed the relocation of over 40 vehicles and 60,000 artifacts here and are building galleries to house and display items that will educate visitors for many generations to come.”

When legendary race-car builder and chief mechanic A.J. Watson passed away, his daughters worked with the museum to have everything from his last shop transported to Lincoln for a special display. “Everything in there is exactly the way it was when our team got there,” Matthews says. “We took hundreds of pictures, so every piece of pipe, every drill bit, oil stains on the floor, everything is exactly the way it was before we took it out. The car in the shop diorama is none other than the Watson-built winner of the 1958 Race of Two Worlds in Monza, Italy. It is on loan to us by our great friends at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum.”

All of the museum’s Indy cars are era-representative: “This Shrike is representative of the ’60s,” Matthews says. “This Mallard was the last front-engine car to race at Indy. Al Unser drove this car when he and brother Bobby were both on the front row in 1970. Every engine in this section has raced at Indianapolis. This pair of original Gasoline Alley garage doors is one of only two that got away when they bulldozed and rebuilt it. We built this diorama so we could utilize the original doors and give people a sense of what the pit garages were really like.”

One fun story concerns the Mallard that Jim Hurtubise raced the last year the car qualified for the Indy 500. Then, for the next nine years, he took it back, got in the qualifying line, went out, and just drove around waving at everybody, with everyone waving back at him. “The last year he took it there,” Kelly relates with a grin, “he parked it in the line and waved around everyone who came up behind him. And when the gun sounded at six o’clock Sunday, he was still sitting there in it. When the other drivers came over to tell him how sorry they were, he took the cowling off, and there was a cooler of beer in there instead of an engine. That was his way of saying thanks for putting up with him for the last several years.”

Finally, the “Bill and Joyce” room is full of things important to their sons, which they added after Bill and Joyce Smith passed away. “When I first came to the museum,” Kelly says, “this chair was sitting over there, and Bill was in it. He would sit there and talk to you, but you didn’t go through those doors [to the second and third floors] without a guide. This place was his toy box, and you could not just come in here and wander around.”

The museum has been a strong focus for the entire Smith family, partially because they created it as a foundation, so things that they personally owned were donated. “When you give away things that are prize possessions, creating a museum to preserve them is the best step of all,” Clay Smith enthuse. “The foundation was set up in 1994, but it really changed from a collection to a museum when it moved to this building in 2001, and it has evolved over the years. We always try to think about what makes it special and how it can be better tomorrow than it is today. I’m really proud of the fact that we’re the number one tourist attraction in Lincoln, according to Trip Advisor.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I got to go there last year and that place is incredible. I didn’t get enough time to really enjoy it. You could easily spend a whole day plus in there. I hope to get back out there soon.

I really need to make a pilgrimage to Lincoln, soon. Great article. Love the passion!

I didn’t know this existed! How can I get my wife to go to Lincoln for a week?

If she likes quilts send her to the International Quilt Museum in Lincoln

This is a museum that photos just do not do it justice.

It is a shame it is where so few will ever see it.

Bucket List, without a doubt.

Toured the museum decades ago as part of delivering some stuff to them, and it was amazing then. I can only imagine how awe-inspiring the place is now. The early Indy stuff, as well as the engineering on display, are likely the only such items you’ll ever see.

I got to visit here while staying in Lincoln for a NASA deployment.

Walking distance from my hotel. Absolutely amazing place. Every time

you think that you’d seen everything there was more. This and the Barber

museum are my favorites.

I’ve been there twice. It changes every couple of years. Twice was not enough. The best museum I have ever been to.

That looks like a very cool place. Lots of cool cars there.

We spent an awesome day there in May 2023… in addition to all of the cars, toys and paraphernalia, I thought it was cool to see the giant HURST Shifter and platform that Linda Vaughn used to stand on as they paraded her around the biggest tracks in the country. We look forward to returning to see the expansion. I understand they’ve recently acquired the entire Daryl Starbird collection from his museum in Oklahoma.

Got there late in the afternoon about an hour before closing time. I just about had to run to see some of the exhibits. What a bummer!

On my bucket list. I’ve been using speedway for 25+ years. Now my rant. Ordered a 9” center section last June. They built it with your ratio and posi unit of choice. Was told would take a couple weeks to ship After 3 weeks contacted them and was told parts on back order.5 weeks out they said it was being assembled and being shipped in a couple days. 6 weeks out called again and they told me parts on back order until October. Canceled order. Ordered center section from Quick Performance and had it in 10 days. Same price with a locker unit instead of trac lok. I live in upper Midwest and summer is short. My hot rod was down for 2 months in prime time driving season. Still use speedway but not as often as before