The basics of Bonneville Speed Week engine classes

If you’ve ever seen a land speed race car, you may have been intrigued by its bizarre proportions, flattened roof, and strange lettering. The first two, naturally, are the product of being modified for high speeds, and we’ll investigate those design elements in a future article. The lettering on each race car that plies the salt at Bonneville refers to its engine displacement, whether or not it’s supercharged, the fuel it burns, and its car class, in that order, as specified by the Southern California Timing Association.

We’ll take you through the first bit of those confusing alphanumeric codes right now.

The first letters of a car’s classification usually reflect the engine’s displacement but sometimes are even more specific. The most common engines found at Bonneville are pushrod V-8s for the larger engine classes and motorcycle engines for the smaller engine classes; however, virtually anything goes. A Mopar 440 big-block with its factory bore and stroke is actually 439.72 cubic inches, putting it right at the upper end of the allowed displacement in the B class. A Supra’s 3.0-liter 2JZ engine would place it in the F class.

| Cubic Inches | Liters | |

| AA | 501+ | 8.210+ |

| A | 440–500.99 | 7.210–8.209 |

| B | 373–439.99 | 6.112–7.209 |

| C | 306–372.99 | 5.015–6.111 |

| D | 261–305.99 | 4.277–5.014 |

| E | 184–260.99 | 3.015–4.276 |

| F | 123–183.99 | 2.016–3.014 |

| G | 93–122.99 | 1.524–2.015 |

| H | 62–92.99 | 1.016–1.523 |

| I | 46–61.99 | .754–1.015 |

| J | 31–45.99 | .508–.753 |

| K | Up to 30.99 | Up to 0.507 |

Notice that there’s a floor to each displacement class as well as a ceiling. It’s not uncommon in the Bonneville record book for a smaller engine to exceed the speed for a larger engine in the same vehicle class. Even if a car with a smaller engine is faster, it cannot break out of its class and attempt to take a record in any of the classes that require a larger engine. It is possible, however, for a car with a larger engine to disable some of its cylinders and compete in a smaller engine class; for instance, a V-8 could be modified to run as a V-4.

The above displacement classes apply to both diesel and spark-ignition vehicles, including rotary engines, although the SCTA calculates displacement in a rotary by multiplying the sum of its swept volume by two. Electric and turbine-powered cars are classed by weight and thrust-powered vehicles aren’t allowed in SCTA competition. While a turbine-powered car may sound like a jet, all of the turbine’s power must be routed to the wheels.

Vintage Classes

Several vintage engine classes at Bonneville don’t follow the class chart above. These classes were made to keep the spirit of ’40s and ’50s racing alive and try, to an extent, to limit modern technology. Electronic fuel injection is prohibited, as are turbochargers, and computers and sensors are only allowed to record data, not to change any engine parameters during a run. Those rules apply to the following classes:

XF refers to a vintage Ford or Mercury flathead V-8 from 1932–53 with a maximum displacement of 325 cubic inches. Production blocks are required.

XO designates a vintage overhead-valve inline-six, inline flathead, flathead V-8 (besides those from Ford and Mercury), or flathead V-12 engine made domestically prior to 1960, also with a maximum displacement of 325 cubic inches.

XXF includes any flathead Ford or Mercury V-8 up to 325 cubic inches that has a custom or modified cylinder head with at least one of the valves in the head. Think Ardun OHV conversion. Overhead cams are not allowed. Any XO engine between 325 and 375 cubic inches will also fall into this category.

XXO is for XO engines between 325 and 375 cubic inches or XO engines with cylinder head modifications similar to XXF. A good example would be a GMC 302 inline-six with a Wayne 12-port head. Again, overhead cams are not allowed.

V4 stands for vintage four-cylinder and designates pre-1935 four-cylinder engines up to 220 cubic inches. OHV and specialty heads are allowed.

V4F (vintage four-cylinder flathead) includes pre-1935 four-cylinder engines up to 220 cubic inches that were originally designed as a flathead and maintains their cam and valve positions.

Induction

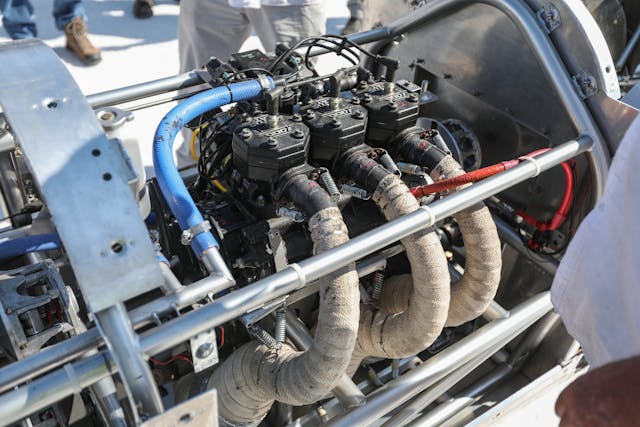

The next letters to decipher in a car’s class designation refer to how it ingests its fuel and what that fuel actually is. Compared to what we started with, this is simple. If a car uses forced induction of any means, it’s considered blown, and gets a B in the letter soup atop its tail or fender or other body panel. Naturally aspirated engines don’t get any designation and are referred to in the record books as “unblown.”

Fuel

All competitors that want to run using gasoline must use the fuel provided for sale on the salt or fuel that’s been approved by the SCTA. Once their fuel cells are filled, the tanks are sealed to prevent tampering. Those cars will run in a gas class and be labelled with a G. Cars burning anything other than, or in addition to, the gasoline available on the salt will be placed in a fuel class, and labelled with an F. Fuel includes alcohol, which powers the Speed Demon; nitromethane, which powered Danny Thompson’s Challenger II; E85, nitrous oxide, hydrogen, or any unapproved race gasoline.

Besides the engine class, there’s still the matter of the vehicle class—but that’s even more nuanced, and we’ll cover that in a future article. We’ll get you caught up on the most important land speed racing classes and lingo before Speed Week 2020 begins on August 8.