The first-hand story of the first Mazda Miata

In the early 1980s, Mazda was flush with capital from record sales and already deep in the design process for the next generation of the RX-7. Having proven to the world that it could solve engineering problems that had flummoxed other automotive companies (Wankel’s problematic rotary-engine design, for example), Mazda was confident in its ability to make its flagship sports car a true “world-class” competitor.

Riding all this momentum and strength, the company aimed to move its second-generation RX-7 upward in the market to meet and beat the Porsche 944, with a long-term goal for the third-gen car to surpass the 911’s performance. Mazda’s “stretch goals” were laudable, but the lofty aspirations left a void in the product line just beneath the RX-7—an opening crying out for a great car.

Meanwhile, the longstanding European supply of lightweight sports cars to America had all but shriveled up, leaving its own roadster-shaped void. Whether due to quality issues, labor unions, or America’s ever-restrictive emissions and crash-protection laws, European manufacturers could no longer supply 40,000 small sports cars to American customers annually.

Mazda product planner Bob Hall, a former journalist who fully understood the sports car market, made the suggestion to upper management that the company should develop an entry-level sports car to sit beneath the second-generation RX-7. The advice did not fall on deaf ears. The Porsche 911 had always had a more affordable showroom sibling, an even Toyota had a pseudo sports-car companion for its Supra in the MR2. A younger brother to the RX-7 made sense.

Bob sent a fax to the home office in Japan, inquiring if Mazda could be profitable with a car that sold only 40,000 units per year. The answer was yes, thanks to Mazda’s flexible assembly lines, which allowed a mix of models to be built in one factory (as opposed to GM and Ford practice, where one model supported a whole factory). Hall’s suggestion led to funding for an initial design study.

Every enthusiast employed by a car company has, as a core desire, a wish to create a performance car. No one doodles minivans in their high school notebooks, after all. Mazda’s small team of planners and designers were no different. I was no different. The new Lightweight Sports (LWS) concept, codename project 729, ignited a fire in Mazda’s Southern California Design Studio. I was hired as the first American engineer into a small skunk-works team that Mazda Japan had created to develop products for the U.S. market.

On my first day of work, my supervisor, Shinzo Kubo, asked what I knew about designing a sports car. I had gone to engineering school specifically to learn how to design race cars, and I had by that point owned, restored, and raced about 20 European sports cars, so I told him I might be able help. Since 1979, as a sort of foreshadowing of my own career, I had been marking up RX-7 brochures with a black Sharpie, blacking-out the roof to make the car a convertible and sketching in an open “mouth” at the front bumper. Needless to say, I was very much primed.

Everyone was. Among the stylists were a couple of Art Center graduates and a long legacy of sports car love, ownership, and appreciation. The product-planning department also held people deep in love with racing and sports cars.

Car companies around the world employ sports-car enthusiasts, of course, but at Mazda’s Southern California operation, we reached critical mass, thanks to our own rabid enthusiasm and an upper-management team that truly wanted to be the largest sports-car manufacturer in the world based on sales. (Mazda achieved that title in 1992, thanks mostly to the Miata.)

So we sat around the office’s little white common area and dreamed up specifications for the perfect 1000-kilogram (2200-pound) sports car. Each of us suggested special features that had endeared us to the cars we had owned: We counted over 65 different sports cars in our collective ownership history, from lowly Austin-Healey Sprites and Triumph Spitfires to Lotus Europas, Jaguar E-Types, De Tomaso Vallelungas, and Lamborghini Countaches. With the Mazda project, we had a blank canvas onto which we threw the best characteristics we could think of.

Informing much more than just the shape of the clay model, we were assembling the 729’s soul—trying to make it far more than just an attractive little car. The thing had to drive and race like the best we had known. And that became the engineering department’s job—to fit a capable sports car beneath the design studio’s skin.

The Southern California studio typically hosted visiting designers from Hiroshima. Those individuals would do a few years at our location, then rotate back home. Designer Masao Yagi was on staff when the initial study was commissioned, and he was given a drawing of the rear-wheel-drive GLC econobox chassis layout to work with. He did an exemplary job of draping a sports-car shape over that clunky and upright package, and that gave upper management something to consider.

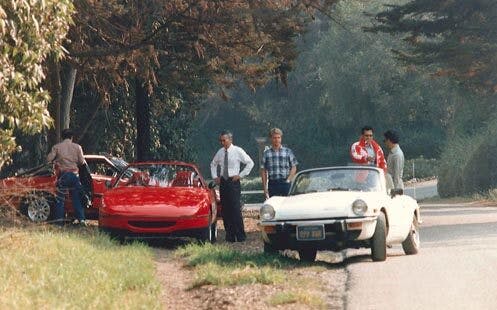

A fiberglass body was made up from Yagi’s model, and we engaged the English firm International Automotive Design (IAD) to build a running prototype. After the prototype had been shipped back to us, we took it to Santa Barbara to drive around, so executives could view the shape in traffic. That was a key policy at Mazda; the company believed potential new cars should be seen and evaluated in their natural environment, not just in a sterile design studio.

I drove that prototype all around Santa Barbara. People were literally chasing me down to ask about it. At one point, I got stuck at a traffic light beside a Porsche dealership and was nervous about someone taking photos. Looking into the showroom, I saw a few people viewing a 944 on display. One by one, they left the Porsche and came to the window, looking at the prototype, pointing and calling for others to come see.

It was basically an ad-hoc focus group, and we could not have asked for a better demonstration of our concept’s attractiveness to the people who actually buy sports cars. That evening at dinner, R&D director Masataka Matsui said, “Maybe we should build this car.” With that, the “Miata” project was funded for a second clay model.

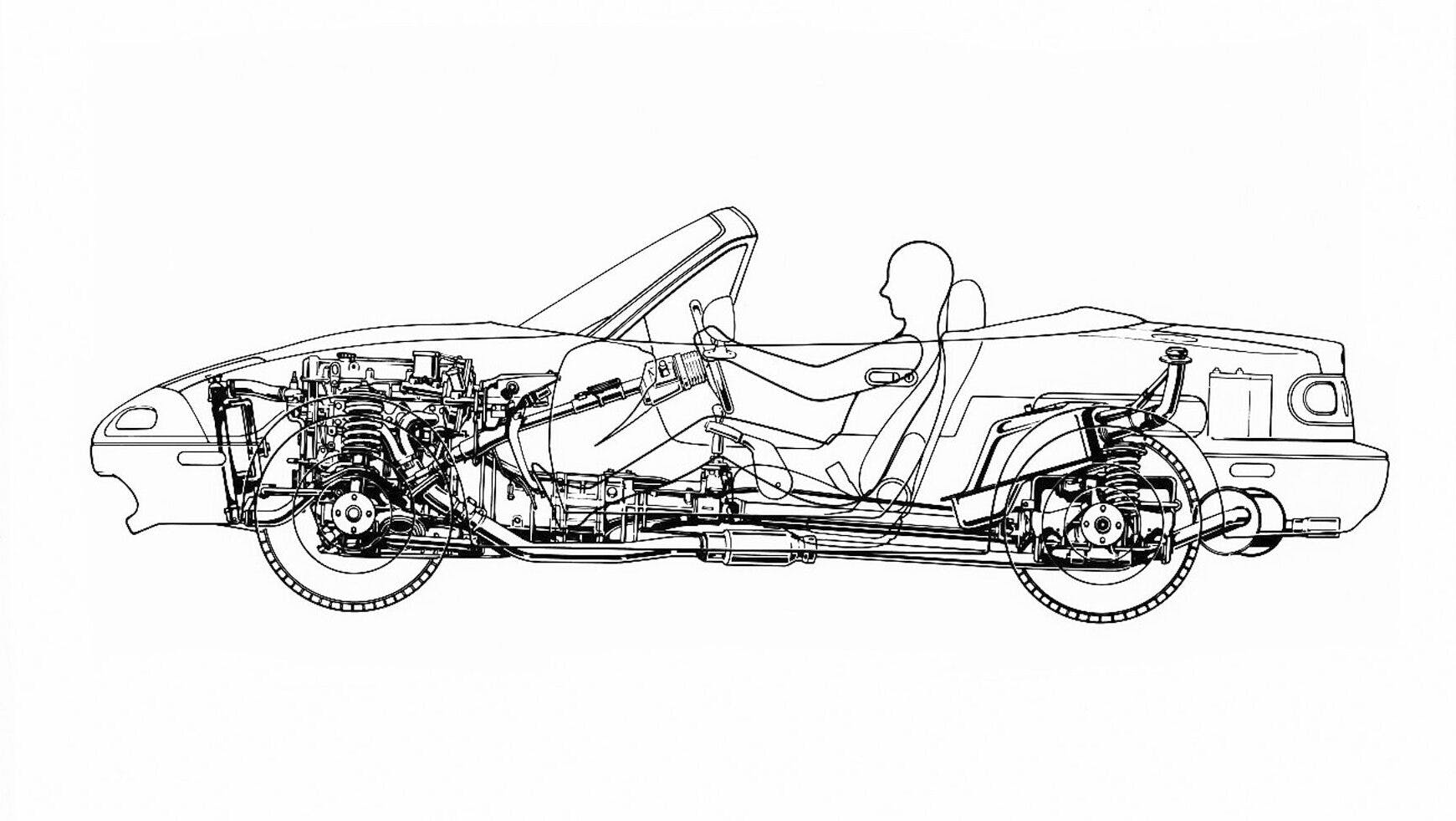

The styling would be its own challenge, but what lay underneath was critical, what makes a car a car. When an aerospace engineer designs a fighter jet, every part has to contribute to flight. Similarly, we compared every proposed specification for the 729 to the Lightweight Sports Car concept, all while embracing Lotus founder Colin Chapman’s motto of “simplify, then add lightness.”

“We can ditch the ashtray, no one smokes any more, anyway,” suggested planner Jim Kilborne, when we discussed reducing weight. All well and good, but at the time, 22 percent of Americans and more than 50 percent of Japanese men smoked, so the ashtray stayed.

“True sports cars don’t need radios,” Bob Hall offered in a meeting. “We’ll make the engine’s exhaust so melodious, [it’ll be] all you want to hear.” We all nodded in agreement, even though eliminating a sound system wasn’t practical. Such was our laser-focus on making the car enjoyable, light, and sporting.

“The car’s beltline has to be low enough so you can see the asphalt out of your peripheral vision, helping you gauge your speed and see apexes.” That was my suggestion. The idea stuck, and “sensing” the road over the Miata’s door top became a key element in how the car communicates to the driver in a corner.

The fever spread, in the best way, to Mazda’s home office in Hiroshima. Everyone on the project was all in, and the essence of a small, race-capable, high-quality jewel of a sports car became a guiding light. Driven by their own passion, enthusiasts in each department in Japan volunteered their time—often after hours—to work on the 729 project. It was as if we were all in love with the same girl, just without the jealousy.

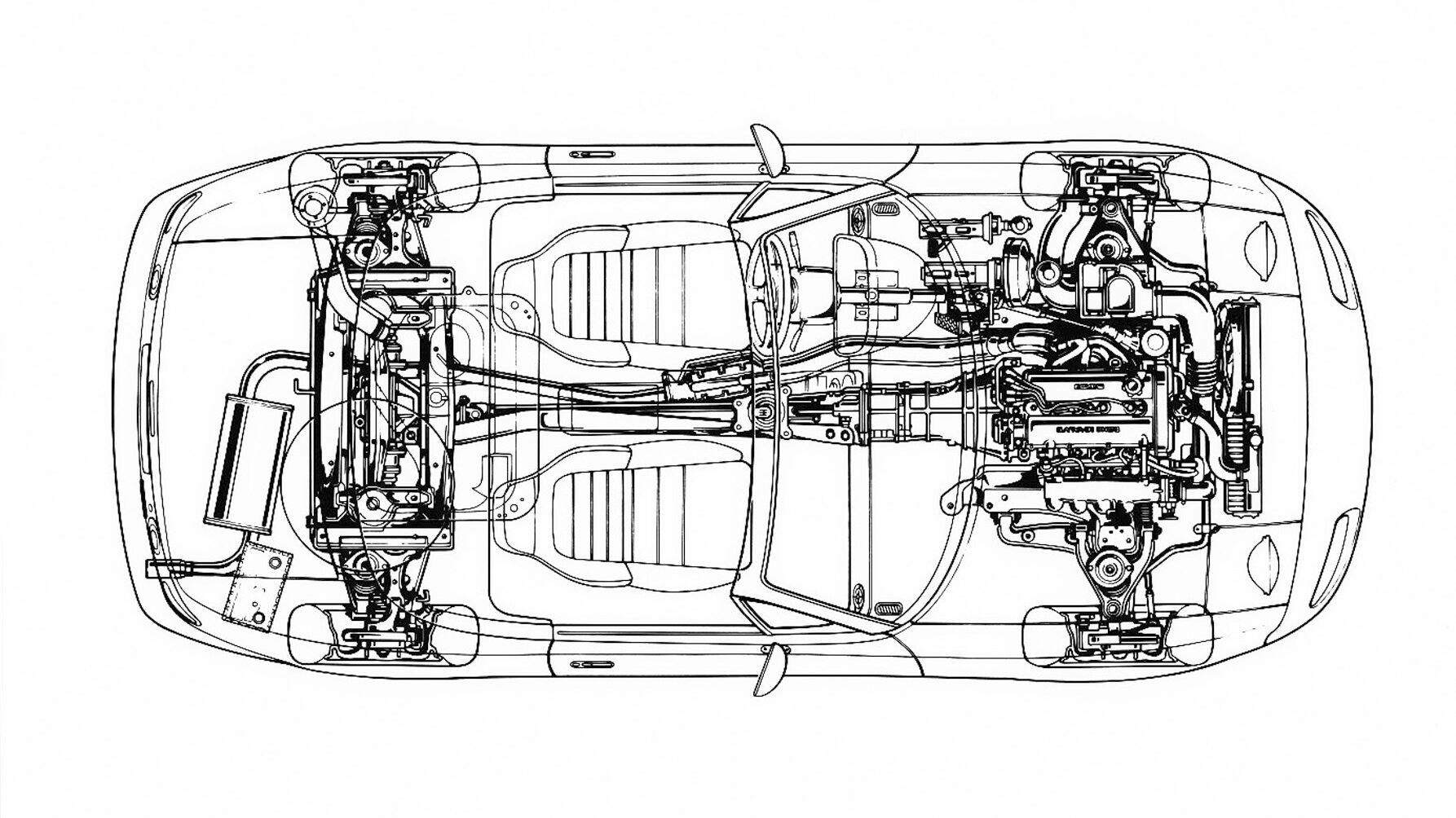

As our work began in earnest, engineering delivered a much more condensed packaging layout for the second clay model—one suitable for a sports car, and that could be easily adapted for club racing. Because no amount of tuning can cover for poor decisions at the packaging and layout stage, we were careful to place the heavy components low and toward the center of the car for balance and weight distribution.

We were dedicated to a front engine/rear-drive (FR) configuration for a number of reasons, the joy of lift-off oversteer among them. We benchmarked the design against cars like the Lotus 7 and Lotus Elan (for driving “feel”), the Porsche 911 cabriolet (for soft-top function and chassis rigidity), and the Triumph Spitfire, MG MGB, and Alfa Romeo Spider (as beloved legacy designs).

Those early design stages held long engineering discussions. Takao Kijima and Jiro Maebayashi, two of the best vehicle-dynamics engineers in the world at the time, kept the focus on optimizing the 729’s handling and grip. As we saw this elegant chassis design come together, the excitement grew. Great credit goes to the late Toshihiko Hirai, who became the car’s program manager and fought so many internal battles at Mazda HQ—first to keep the project alive, and then to find tooling money to construct the special parts required to make the 729 work.

One of these parts the Power Plant Frame (PPF), the long metal brace that ties the Miata’s engine and transmission assembly to its differential. This part was purposefully engineered to allow quick on-off throttle action at 6000 rpm in second gear during full-g cornering without undue drivetrain wind-up—a quality that can kill a car’s controllability during, say, autocrossing or track lapping. I had dug up some details on the torque tube used in the Ferrari Daytona, which performs a similar function, and incorporated it into the design. Hirai found the money in the development and tooling budget to retain this important feature, along with the bespoke double wishbone suspension at each corner, the unique fuel tank tucked in front of the rear wheel’s centerline, and the thousands of other small but special choices baked into the Miata’s character.

People like to compare the Miata to the Lotus Elan. From an engineering standpoint, though, it is more akin to a four-cylinder, nine-tenths-scale Ferrari Daytona.

Back in the studio, Shigenori Fukuda oversaw the stylists working to wrap something attractive over the new chassis layout; Tom Matano, Mark Jordan, and Wu-Huang Chin were sketching like crazy to get our model into shape. Designer Koichi Hayashi was onsite from Mazda Japan to coordinate body design, and we had something on the floor for viewing, analyzing, critiquing, and updating as fast as our modelers could reshape the clay.

This went on for months as the second model became more and more viable. Engineering and design fought over hood lines, door cuts, cowl points, and the usual “hard points,” the points where a car’s guts meet its skin. The body designers had a difficult job, of course, because everyone in the building had an opinion. I had my own and recall reminding the designers that “the tooling costs for a beautiful fender are no higher than for an ugly one, so why don’t you work a little harder on that fender you’ve got there?”

Design of the underpinnings went a little easier. We engineers had only to use the best designs possible for our parts, no human opinion, because math and physics lead to irrefutable conclusions. In the end, the second clay model made a great sports car, but it was not ambitious enough in terms of visual passion, so a third clay model was commissioned. That’s where Chin’s gifts came into play, as the final surfaces were given character and grace.

We shipped the final design package—clay model, engineering drawings, and specifications—over to Japan, where designer Shunji Tanaka tuned up the final body surfaces and developed the interior design. Only then did the very difficult work of designing the nuts and bolts of an actual car begin. Taking a car’s design from concept, even a highly defined one, to reality is always a difficult job, and it often goes awry. But the steadfast Hirai sourced support from key internal departments and protected the fundamental design elements, all of which kept the 729 on track the whole way.

Throughout the duration of the project, there were endless conversations about setting targets and challenging Mazda’s home team to meet them in clever ways. In the transmission department, we had a long talk about shift-rod notch design, chamfer angles, detent-ball spring rates, and synchronizer design, all of which affect a shift lever’s feel.

As I left the meeting, I said, “Just buy a worn-out BMW 7-series with a five-speed and a Jaguar E-type transmission, then blend the feel of those two.” That’s how the Miata’s shifter came out so well.

We also agreed that the soft top had to be able to be closed, one-handed, by an American woman sized in the 50th-percentile, while seated behind the wheel. No one had ever made such a soft top, though the roof on the Alfa Romeo Spider came very close. When Mazda engineers hit that difficult target, they simultaneously created the industry’s best leak-free soft top. For two years, conversations like that went on, and optimization continued, system by system, until finally, the 729 was tooled and ready for testing, including crash tests and final suspension tuning.

In the summer of 1988, U.S.-based product manager Rod Bymaster was casually browsing etymologies in the dictionary when he found the word “miata.” It means “reward” in Old High German, and the name was set. I drove an early production prototype on an autocross course in late ’88 and could not believe how well the dynamics had come together. It drove as well as it looked. Mazda had breathed life into a concept that started as a glimmer in a few fanatics’ eyes just six years earlier. In July 1989, the company filled that void in the market with a masterpiece of a design and execution, the distillation of all the great lightweight sports cars that had come before.

Designed by enthusiasts from around the globe, made by one of the highest-quality engineering and manufacturing companies in the industry, the Miata rolled out and the marketplace rejoiced.

More than one million units later, I guess we got it right. The current Miata MX-5 (ND) carries the same DNA, to the delight of its owners. To be honest, at first, we only wanted to make about a dozen Miatas—just enough so we could each have one for ourselves. I’m glad many of you feel the same way.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I bought my Miata in 2011 a hard top touring model.I drive it on weekends during summertime and stays on my garage in winter time.I used to live in rural Ohio (recently moved to Illinois),with those hilly and winding roads,and that’s where i usually drives it with the top down,to enjoy those beautiful vistas as the Miata glides sonorously,under me, with the sweetest sounds ever coming its small but very efficient 4 cylinder engine..I also owned(now passed to my son) a 911 Porsche Carrera but,this car is a beast,that likes to be driven fast on the freeways.My tiny Miata is an antidote when i crave for a more idly drives and enjoys the spirit of wilds..I still have the Miata with 11k miles on it ,and own several Audis as well ,but nothing compares when I drive this tiny car.

My father worked for Airflow Streamlines Body Engineering division in Northampton UK, and worked on the prototype with IAD from Worthing

Michael – That is great to hear. IAD was a very capable outfit with some very talented people working for them. All of our clay modelers came from IAD in the beginning, and it was very poetic having all the British accents in the studio for years while we crafted the reincarnation of the small European sports car.

Live in Canada and bought the first one to arrive in my home town for my wife. That was early 1990 and at 340000 km later it is still in excellent condition. Two grandsons are fighting over who will own it when I am ready to pass it on. (might be awhile) Great article enjoy reading Miata stories.

Great story and no disrespect to the author intended, but without a deeper dive into the details it’s tough to swallow the fact that a torque tube (PPF) makes the Miata and Daytona engineering brothers…..or even second cousins.

The Miata is a unibody while the Daytona is body-on-frame. The Miata’s transmission is forward-mounted, the Daytona’s a transaxle. Miata’s engineers obviously cared about weight savings, while that meant not much more than skinning the doors in aluminum to Mr Ferrari.

The Elan comparison obviously owes to the general size, shape, and dynamics of the Miata, with the PPF bearing a strong resemblance to the central part of the Elan’s backbone chassis.

From a spiritual standpoint there’s no question: the Miata and Daytona are from different planets. The Miata and Elan? They might as well be fraternal twins.

Woodrow – you make some thoughtful comments. If you dig deep enough, the analogies do fall apart.

After three decades of hearing how we “copied the Elan”, I was offering an alternative viewpoint. The Elan is also a (fiberglass) body-on-frame design with strut suspension, and we never considered any of its engineering features in our work. The Daytona has double wishbones all around and a torque-tube to stabilize the powertrain, similar to our PPF (and neither are not part of the frame/unibody). From an engineering standpoint, the basic layouts and suspension designs are more similar between all four generations of Miatas and the Daytona ( and a host of other high-level sports car designs, such as the Ferrari 275GTB, XKE, etc.).

You’re right about the transaxle, when you look closer at both designs. Ferrari moved to a rear transaxle as a way to increase the overall polar moment of inertia of the vehicle (as did the Corvette C4,5, 6 & 7 engineers, and as Porsche did with the 924, 944, and 928, and as have other OEs). This makes a high-speed GT car much more stable at 100+ MPH. We were going for high dynamics with the Miata, so we adopted a “front-mid” engine layout to reduce the polar moment of inertia and create a car with high-response to steering inputs, etc.

I’ll let you in on a secret: If you want to see the true fraternal twin for the Miata, look up the OSCA 1600 GT built by the Maserati brothers circa 1961

The Elan has double wishbone’s in front and Chapman struts in back. You seem to protest too much with comparisons to the Elan.

The Elan has double wishbone’s in front and Chapman struts in back. You seem to protest too much with comparisons to the Elan.

You are correct about the Elan: The rear struts are “no bueno” when it comes to camber patterns, but the Chapman Strut is a clever way to incorporate a half-shaft into the suspension system. Good engineering always tries to make each part do double (or triple) duty, and no one needs me to tell them that Colin Chapman was one of the best at such designs. Porsche’s original 911 (and identical 914) front strut with a torsion bar nested in the fore-aft lower control arm tube is the most elegant of strut solutions, but again, with deficient camber gain on compression.

Great story of a great car. I had a1994, loved it. I will have another soon.

Wonderful Mazda history! I have loved sports cars since driving a friends brand new ’59 MGA in ’59. I have had at least one or two sports cars as my every day drivers. I have a ’04 Miata NB, which is the best all around trouble free car I have ever had and most fun to drive. I’m 85yrs old and have 87K miles on her and have only replaced belts, battery, and tires, also never any oil leaks!

I, a man larger than a 50th percentile American woman, owned two NA Miata’s and nearly destroyed my rotator cuff in my only attempt to raise the top from the driver’s seat. Never tried a second time. As for that top that didn’t leak…the reason I bought the second one was that my left leg was always wet when I drove in even a light mist. The second one leaked worse than the first.

Love my little Mazdarati! Small budget, big fun.

For my third convertible I strongly considered a Miata, but I prefer haveing a back seat and storage space inside the car. My biggest question about the newer Miata design is why was the glovebox removed? Why? Why? Why?

BTW – my 2-3 year search ended when a friend suggested I buy his 2008 128i convertible. I did and it’s a good, fun car with interior storage, a back seat, plenty of power, and great handling. Plus, I learned after owning it for a while they are coveted and collectable.

I asked the Miata salesman if it came in a slightly larger size, but it probably wouldn’t be as much fun if it did. My red NB is delicious, once I learned how to easily get in and out.

I’ve had three NA Miata’s and have loved every minute of ownership. Number one was a ‘91 (White with Black cloth) that was my weekday daily driver and my weekend autocross partner. Number two was a ‘93 LE (Black with Red leather and removable hardtop). Also fun but still underpowered especially with the AC on. Number three is also a ‘93 LE. This one, however, has a Jackson Racing supercharger, an intercooler, a Mishimoto double-core aluminum radiator and a MagnaFlow exhaust. She delivers many smiles per mile here on the island of Saint Croix. The ‘97 NSX-T and ‘06 Carrera S are sweet highway cruisers when we’re on the mainland but the LE here is a twisting mountainside/seaside road delight.

We love our 02 brilliant yellow NB. I’m 6’2 and have no problem fitting in our Miata with top up or down. Spent many years doing road trips on our Harleys so I consider the luggage capacity of the NB as extremely adequate. In my younger days I owned an MGB, TR4A and a TR250 and this NB is a combination of all that was great about them. With the added bonus of being extremely reliable. Thank you Mazda!!