How MTV’s DNA, the NYC police, and a forged contract led to Subaru of America

This article originally ran on this site in June of 2021. After seeing Jeff Dunham’s Bricklin SV-1 on Jay Leno’s Garage yesterday, we couldn’t help but think of Subaru of America, a company founded by the same man who designed that odd, gull-winged sports car and gave it his name: Malcolm Bricklin. Enjoy! —Ed.

Everybody loves a good origin story. Bruce Wayne’s parents. Peter Parker’s uncle. Kal-El’s trip from Krypton. The story of how a humble motorscooter helped found one of the most recognized brands in America is just as compelling.

It’s hard to imagine now, when you have to be a guy who started a payment-processing company with his dad’s money to eventually launch rockets and build electric cars, but back in the 1960s, ordinary schmoes with a decent suit and a dream could launch an international business. That’s what was going on with Malcolm Bricklin circa 1966, a young guy just out of college with a few bucks left over from a building supply company he started after leaving the University of Florida.

Bricklin had moved back to the Philadelphia area and was hungry for the next big thing. “I got introduced to a man by the name of David Rosen,” Bricklin says in an interview with Luminary’s Driven Radio Show. “David would put things like cigarette machines in bars and restaurants around the Philadelphia area.” Bricklin wasn’t much interested in selling cigarettes, but Rosen told him: “I got this thing in Italy that they’ve been bugging me about, and I think you’re perfect. It’s called a Cinebox.”

Bricklin described the Cinebox as a “visual jukebox,” where for 25 cents, a patron would see a short film along with wild movies in the mold of the Beatles’ 1964 hit film A Hard Day’s Night. Bricklin went to Milan to see the movie booths, which were built by Innocenti Corporation, the Italian conglomerate which also built Lambretta scooters under license.

Bricklin loved the idea and signed on immediately, only to find after a visit to Hollywood that nobody produced the kind of short music movie, what MTV would eventually launch as the music video in the ’80s. Instead, all he managed to find was R-rated pornography.

“Although I enjoyed watching it,” Bricklin says, “that’s not the business I wanted to be in, and I couldn’t convince anybody to make me a musical film.”

The impasse led to a rather desperate discussion with Innocenti, and one that would eventually set Bricklin on the path to become an automotive industry executive. The company had a warehouse in Long Island with 25,000 Lambretta scooters that, for whatever reason, it simply couldn’t sell in America. Bricklin went to the Lambretta facility in Long Island and found that “They have two nice guys, they speak broken English from Italy, they take two-hour lunches, and if you want one of these things you gotta send them a check.” The, after some indeterminate amount of time, the scooter would appear.

“It’s not a really good way to sell something that very few people want,” said Bricklin.

So he recommended that Innocenti fire their erstwhile Italian salesmen, set Bricklin up in an office in the Time and Life Building in Manhattan, and provide him $5000 a week. To Bricklin’s surprise, Innocenti agreed, offering him a one-year contract to move the bikes.

Through a connection, Bricklin hit on success: He ended up selling a thousand, then many multiples of thousands, of scooters to the New York City Police Department, first as a way to make New York City’s parking enforcement officers mobile, and then to put cops on wheels in Central Park, when that jewel was considered one of the most dangerous places in the city. Bricklin and his partner took out a $15,000 ad in the Police Gazette advertising the Lambrettas, with a testimonial from the NYC police. “By using the Lambrettas in Central Park, it kind of opened up the park. It sort of made it a place where you could actually go and enjoy the park. It really did cut down on the crime,” Bricklin says.

Buoyed with his New York City success, Bricklin went looking for other opportunities to put Americans on two wheels. He found some traction selling scooters to gas stations who would rent Vespa and Lambretta scooters in tourist areas. “I saw that they were getting $15 an hour to rent these things,” Bricklin says. “That was at a time when these things only cost a couple hundred dollars. We’re talking about a real return on investment.”

But there was a huge issue in the rental market: the manual transmission. At the time, most people did know how to drive a car with a manual gearbox; but riding a scooter was something else entirely. Vespas and Lambrettas shifted gears via a twist of the left handgrip. It’s not particularly challenging if you own one and have time to acclimate, but if you’re just renting the two-wheeler for a couple of hours in Florida, you’ll stand a decent chance of getting hurt. Most of the companies that rented these bikes had little in the way of insurance and would get sued out of existence after their first summer.

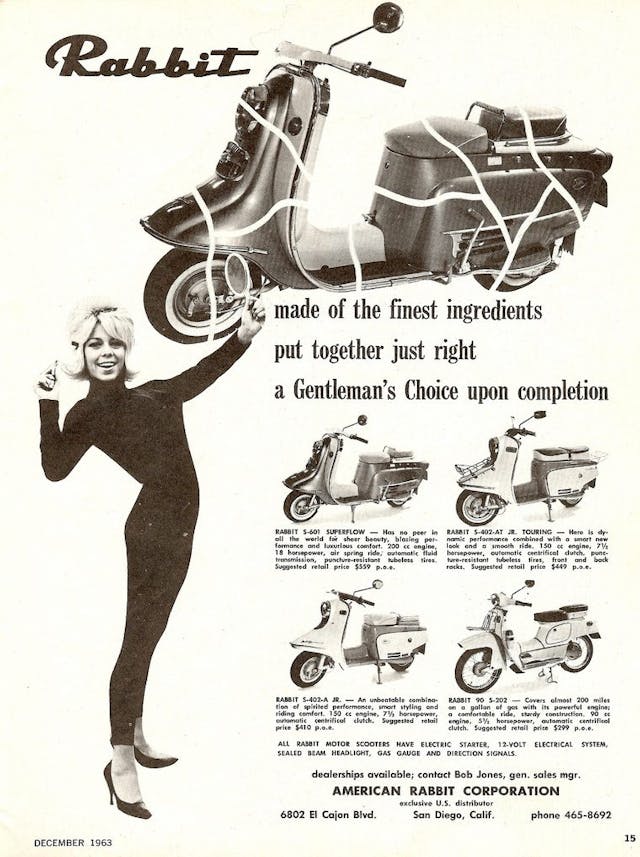

Bricklin handled part of it with a dollar-per-rental insurance fee to State Farm, but the danger still remained, until he read something intriguing. “I read a little ad in the Wall Street Journal, about a guy who has 450 Rabbit motor scooters in the New England area,” Bricklin recalls. “So I fly to Boston to meet him, and he has himself a little airplane, and he has 450 scooters on rental, and they have automatic transmissions. Oh my god, I think I died and went to heaven. I’ve got automatic transmissions and I have insurance.”

The Rabbit was the product of Fuji Heavy Industries, which had been in the transportation and aerospace business since 1953. The first Rabbit scooter, the S-1, was essentially a reverse-engineered version of Powell’s two-wheeler, a crude machine with an eight-inch wheel and no suspension. In 1957, though, Fuji set out to build a better bike than the Italians, and succeeded. Their top-of-the-line model was the Fuji Rabbit Superflow S601, a true luxury scooter that beat anything available at the time with innovative features that made riding one as easy as twisting the throttle.

These bikes used the basic scooter design pioneered by Lambretta: a sheetmetal body hung from a strong tubular steel chassis. Attached to that engine was a beast of an engine: A 200-cc engine capable of rocketing these handsome bikes to 65 miles per hour. While Vespa and Lambretta owners would be kicking their bikes over for years to come, the Rabbit Superflow S601 came standard with electric start, another feature that would make these bikes a lot more appealing to the swells renting bikes on Martha’s Vineyard. The rear suspension was an air shock, which riders could inflate or deflate depending on whether they were carrying a passenger.

The key, though, was the Superflow torque converter. This wasn’t some belt-drive snowmobile transmission; it’s a fluid-filled converter like you’d find in front of a TH350. Riders would step through the Rabbit’s attractive bodywork, turn the key, push the start button, release the parking brake, and whoosh off to their destination at fifteen bucks an hour. “Made for the enjoyment of a gentleman,” claimed the marketing materials from American Rabbit Corporation, the San Diego-based importer of these innovative bikes (more on them in a minute).

As if to accent the “gentleman” part of the marketing plan, in 1959, Fuji paid for a barnstorming tour of Europe for fledgling conductor Seiji Ozawa, who would later become the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 29 years. “Seiji Ozawa had pestered companies all over the country for sponsorship that would fund his voyage to Europe and help fulfill his dream of learning classical music in the place of its birth,” read an article in the Bangkok Post. “Only one firm—Fuji Heavy Industries—was prepared to take a gamble on this precociously talented young man, supplying a moped to help him get around the continent.” The “moped” was a Rabbit S201. At each stop, the guitar-wielding, scooter-riding Ozawa set up connections between local distributors and his Japanese benefactor.

The Japanese scooters were an easy sell for Bricklin, who agreed to partner with the Boston-based Rabbit rental agent and pay off the $75,000 loan he had obtained with a local bank. For his investment, Bricklin allowed his partner to keep the rental revenues, and he secured the North American distribution of these amazing bikes.

Or so he thought.

Remember American Rabbit Corporation? They were the sole distributor in the United States, not Bricklin’s new partner. “I get a Telex together to Fuji, telling them how excited I am, and how do I order a couple thousand scooters,” recalls Bricklin. “I get a Telex back asking who am I, and don’t I know that they sold their [Rabbit] factory to Israel, and that they’re in the process of dismantling it?” The last Fuji Rabbit scooters had rolled off the line just before Bricklin inked his deal.

Bricklin suddenly found himself with $75,000 invested in a distributorship through some kind of a forged contract. “All they know is that they have to be nice to me,” Bricklin says, recalling his first trip to Fuji. “We meet with the board, and everybody’s really sorry I got screwed.”

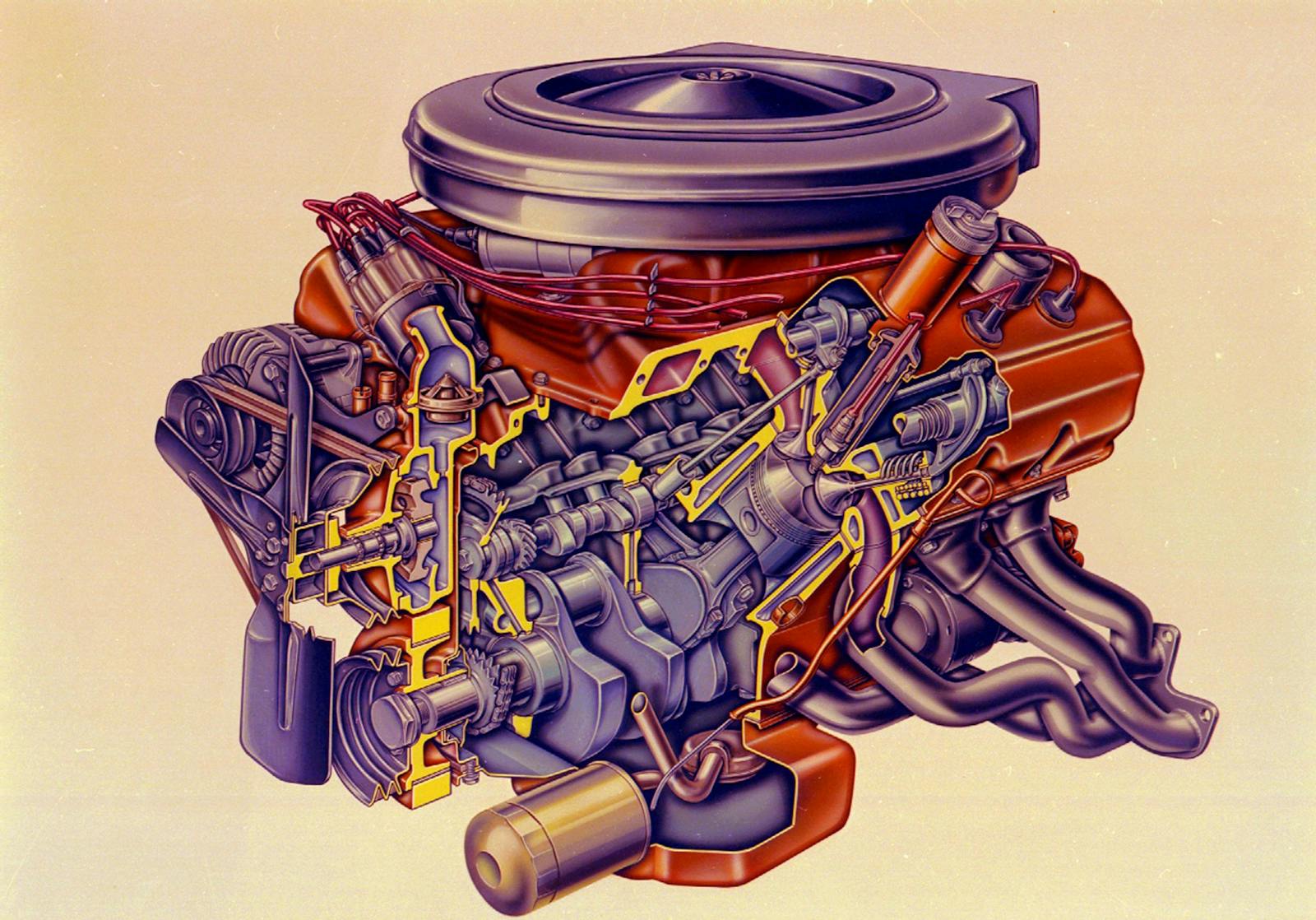

To salve Bricklin’s hurt feelings and his bedraggled pocketbook, Fuji executives took him on a tour of the plant, where he saw the Subaru 360 and the upcoming Star, marketed in Japan as the FF-1. “I really wanted that car,” Bricklin remembers. The 360 was the product he was offered, though. Thanks to a 1000-pound threshold, the 360 wasn’t required to comply with NHTSA’s new FMVSS safety requirements, something that Bricklin figured he could exploit for the first few years until a proper car like the FF-1 came his way.

Bricklin founded Subaru of America to import the 360, on the strength of America’s love for small air-cooled, rear engine cars like the Volkswagen Beetle, but the 360 was never greeted warmly here. A 1970 issue of Consumer Reports labeled the car “Not Acceptable,” essentially sealing its fate in a cresting wave of consumer advocacy after the publication of Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed in 1965. In 1971, Bricklin left Subaru and launched a racing franchise—essentially a go-kart track with adult-sized cars—called FasTrack, which he used as a means of disposing of 10,000 360s he had imported. Bricklin hired Meyers Manx creator Bruce Meyers to develop a fiberglass body for the cars, and fitted them with nerf bars.

The idea never took off, but Bricklin continued to push forward. He developed his own car, the Bricklin SV-1, in 1974; imported Zastava automobiles from Yugoslavia under the Yugo brand beginning in 1985; and, in 2002, embarked on a three-year quest to be the first importer of a Chinese automobile into the United States.

53 years later, Bricklin is still hustling. In 2013, Rolling Stone called him “brash, bombastic, and pathologically prone to betting the farm on pie-in-the-sky automotive endeavors.” With a network of 600 dealers from coast to coast, and a new 250,000-square-foot headquarters in Camden, New Jersey, Subaru of America proves that Bricklin wasn’t the P.T. Barnum he’s often made out to be. And according to Subaru’s national sales training manager, Mike Whelan, there’s still a Fuji Rabbit in SoA’s collection.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I like Bricklin’s SV-1. It was pretty cool for the time. We have him to thank for getting Subaru here and I have enjoyed a few of those cars in the past. Still don’t know why he decided to do the Yugo.

I purchased the Rabbit scooter for the museum when I was employed at the Subaru Technical Center. I be!I’ve it was moved to New Jersey when the tech. Center was closed.

I test drove a Subie 360 when they first hit America’s shores, and was pleased to find a car that my Renault 4CV could outrun…and in fact I think my Fiat Topolino would have given it a run for it’s money to about 35 or so when the Fiat ran out of 3rd gear…