East Coast coachbuilders had their own take on custom looks

In the days before the invention of the automobile, the most widely used mode of transportation was the horse. One horse was sufficient for one person, but most people did not keep large herds or teams. This is part of why carriages came into favor, and those horse-drawn methods of travel varied by wealth and social standing.

When high society wanted only the very best in carriages, firms such as Brewster were sought out for their ability to create bespoke rides. As automobiles became prevalent, carriage builders turned their attention to creating coachbuilt bodies for luxury automobile manufacturers. By using the same craftspeople and level of detail employed at their firms, coachbuilders leveraged their respected names and reputations to venture forth into a new world of society—a horseless realm.

For 2023, the Greenwich Concours d’Elegance will celebrate those well-established and respected firms in the New England, New York, and Mid-Atlantic areas. These locations benefited from their Atlantic seaports, access to railroads and timber forests, and ample talented workforces, as well as wealthy metropolitan areas nearby.

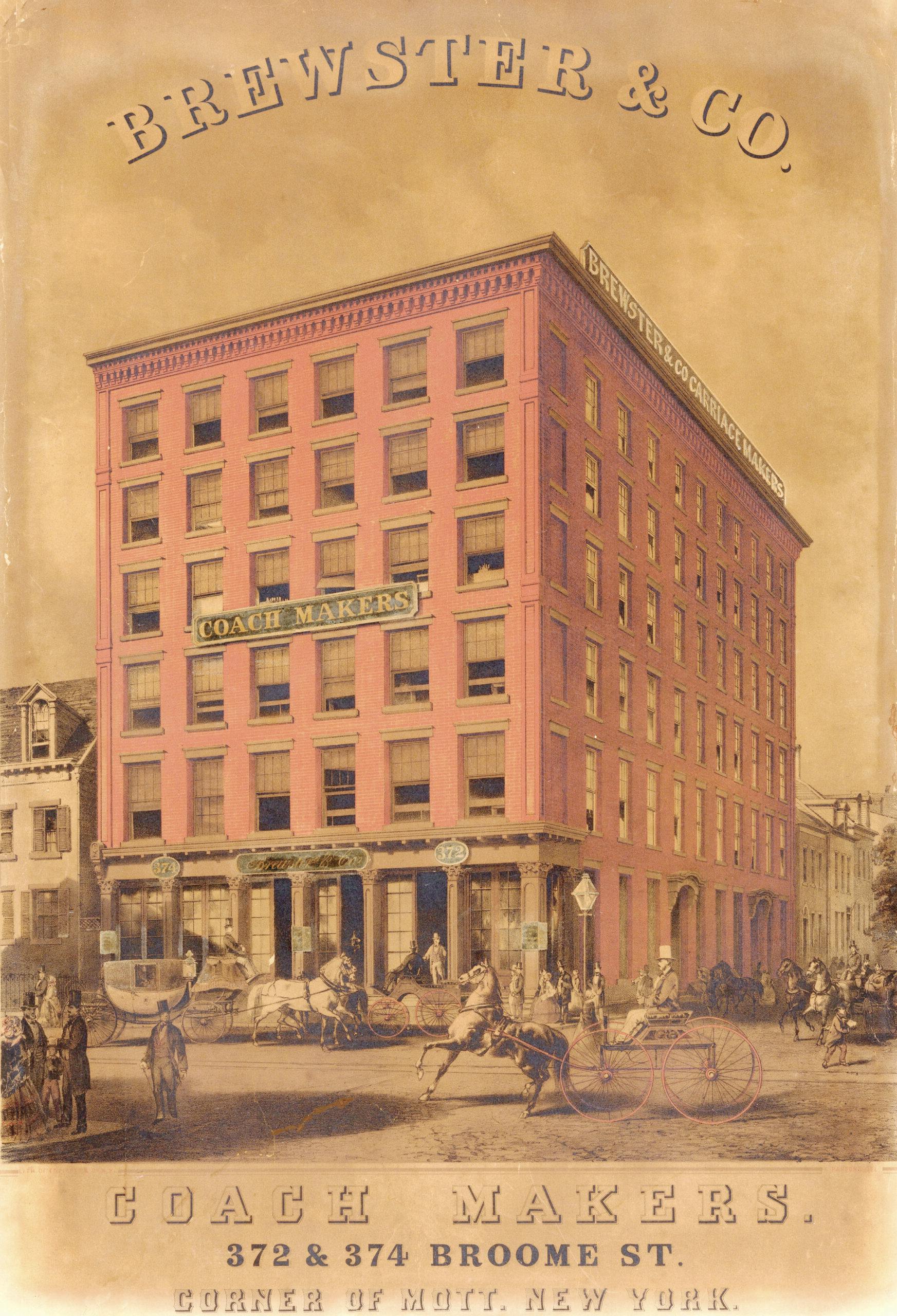

Brewster & Company

One simply cannot discuss American coachbuilding without mentioning Brewster & Company, which has more than 200 years of coachbuilding history. Company founder James Brewster’s roots in carriage building went back as far as 1804, when he was a young apprentice learning the trade at the Northampton, Massachusetts, firm.

With the emerging automobile market, it was only a matter of time before the well-to-do would come to Brewster to craft a body for a car, and in 1905 Brewster did just that. By 1911, the firm built its last horse-drawn carriage, signaling the end of an era.

During this same period, Rolls-Royce could not help but notice the large American market; even before World War I, the automaker had been planning to set up manufacturing in the U.S. In 1919, Rolls-Royce of America (RRoA) was open for business and started producing motor cars in Springfield, Massachusetts; quite naturally, Rolls turned to Brewster for coachbuilt bodies. By 1924, however, it was apparent Brewster would not be able to continue much longer. Rolls-Royce started negotiations in 1925 and in 1926 acquired the historic coachbuilding firm. In turn, during the early 1930s, RRoA started experiencing declining sales of Springfield New Phantoms due to the Great Depression; the Rolls-Royce’s American arm eventually went bankrupt, building its last Springfield car in 1933.

The reputation of Brewster survived, however, with the Brewster family reacquiring the coachbuilding firm that same year. Brewster started coachbuilding once again, using new Ford V-8 chassis from 1934 to 1936, as well as a handful of other customer-supplied chassis from companies including Buick. Alas, this venture was short-lived, and Brewster declared bankruptcy, with all assets sold at auction in August 1937.

Brunn

Like Brewster, Hermann A. Brunn’s coachbuilding history started in the carriage industry. His uncle Henry had already established a carriage shop in 1882 in Buffalo, New York. Nephew Hermann worked for his uncle; unfortunately, uncle and nephew could not agree on the importance of the automobile to their trade, with Henry dismissing these new inventions. Hermann left his uncle’s business and set up Brunn & Company in 1908.

When the new Lincoln debuted in 1920, the bodies on the luxury chassis were perceived to be stodgy and lacking style. Lincoln execs contacted Brunn, asking him to come to Detroit and offer some design guidance. After much scrutiny, Brunn was offered the chance to redesign the entire Lincoln line. Brunn came up with 12 new designs for 1923, by which time Ford had taken over Lincoln.

Working with the new Lincoln Zephyr of 1936 proved a challenge for Brunn, as converting a unitized body was much more difficult than starting from scratch. Brunn was in luck, as Buick’s Harlow Curtice commissioned Brunn to build a one-off show car based on the Roadmaster chassis in 1939. Brunn designed other show cars for Buick before the project was killed off following complaints by the Cadillac division of GM. Hermann A. Brunn died in 1941, and his passing marked the end of Brunn & Company.

Derham Body Company

Joseph J. Derham got his start as an apprentice in the carriage-building trade. With the Main Line of Philadelphia practically at his shop’s door, Derham had the advantage of many wealthy families that resided along the route. Derham’s reputation resulted in him creating semi-customs for luxury car dealerships wanting to offer unique bodies. At one time, Derham was even building bodies for LeBaron Carrossiers before it had such manufacturing capabilities. Joseph J. Derham was able to maintain this balance of catering to a client’s every desire, along with small runs of semi-customs, until his untimely death in 1928.

The 1930s were kind to Derham the company, with the firm creating some truly wonderful bodies for Duesenbergs, Packards, and Franklins. Although other coachbuilders failed during the Great Depression, Derham’s Main Line clients once again provided it with enough orders to keep the company prosperous. Acquiring a Plymouth-DeSoto franchise in the 1930s helped Derham supplement revenue; this relationship resulted in contracts for special-bodied Chryslers and Imperials.

Derham was able to not only survive the Great Depression, but also World War II. Rather than close its doors during wartime, it took on government contracts for both aviation and naval items. After the war, and with much less competition, Derham received several custom orders from clients. These included a pair of restyled Lincoln Continental coupes for famed designer Raymond Loewy and his wife; a pair of Chrysler Continentals based on Ford’s model at that time; and a unique 1927-style body on a current Imperial chassis for Marjorie Merriweather Post Davies of the Post Cereal fame.

When Joseph’s son, Enos, died in 1974, it marked the end of one of the longest-running coachbuilders in American history.

LeBaron Carrossiers

If you were alive at any point between the ’60s and ’90s, you were probably exposed to the many Chrysler products bearing the name LeBaron. In fact, the name LeBaron goes back to 1920. Founders Thomas Hibbard and Raymond Dietrich each got their starts working for Brewster in the design department.

Hibbard and Dietrich focused on creating stunning designs to sell to the firms capable of bringing those ideas to fruition. To give their designs more credence, the name LeBaron Carrossiers was chosen to provide a sense of French elegance. Ralph Roberts joined the firm in 1921 to handle the books; later, both Hibbard and Dietrich left to further their careers elsewhere. Roberts found himself in charge of LeBaron as both head designer and administrator of the firm.

By the mid-1920s, LeBaron was producing approximately 200 bodies a year. Briggs Manufacturing Company, the largest body builder in the Detroit area, had become familiar with LeBaron and purchased the business in 1927. Ralph Roberts continued with the firm, eventually setting up his headquarters at the Briggs plant under the name of LeBaron Studios. Briggs supplied bodies to many leading manufacturers, with some of the most stunning designs going to Chrysler and Imperial—especially the Thunderbolt and Newport of 1941. Chrysler bought Briggs in 1953 and acquired the LeBaron name. Chrysler made good usage of LeBaron’s reputation for quality and tasteful design, affixing the moniker to many models for four decades.

Rollston

Rollston founder Harry Lonschein learned coachbuilding while employed at Brewster starting in 1903. There he was able to appreciate some of the finest chassis supplied by the world’s leading luxury automobile manufacturers, including Rolls-Royce. As Rolls-Royce of America was opening its new Springfield facility, Lonschein and two partners formed Rollston as a gesture to his favorite brand.

Rollston took pride in its extremely sturdy, over-engineered bodies. Rollston was favored by New York Packard dealership’s custom body manager Grover C. Parvis. Because of this, much of Rollston’s work went on Packard chassis. During Rollston’s most prosperous years in the 1920s, it averaged about 54 bodies a year; during the Depression, however, those numbers declined to about 20 per year. By April 1938, the firm had closed its doors, but soon reorganized under the name Rollson with help from Packard with a small-run contract for town car bodies. As with Derham and others, Rollson survived during and after WWII by manufacturing goods for government and military contracts, as well as converting unit-bodied cars into special-purpose ones.

Willoughby Company

It seems that Edward A. Willoughby did not acquire any direct skills by working in the trade. He gained his business knowledge working with country stores and eventually becoming general manager of the R. M. Bingham Co., a vehicle manufacturer in Rome, New York. He then took control of the Utica Carriage Company, which was in bankruptcy. Willoughby later bought the business.

The Willoughby Company was formed in 1903 to manufacture carriages, sleighs, and automobile bodies. After Willoughby’s passing in 1913, the firm was taken over by his son Francis, with Ernest Galle serving as head designer. Under the direction of Galle, Willoughby’s designs focused on comfort with conservative styling. In 1914, Studebaker awarded Willoughby with a contract to build more than 1000 closed bodies. With this contract came a need to double Willoughby’s workforce. Galle hired Martin Regitko, who would become the new chief designer after Galle’s passing in 1918.

Willoughby did not have the advantage of nearby wealthy clients the way Derham did. As a result, many of its orders came in the form of contract work, in particular from Rolls-Royce of America. Francis Willoughby was elected president of the Automobile Body Builders Association in 1923, a testament to the firm’s acclaim.

When Rolls-Royce acquired Brewster in the mid-1920s, Willoughby was left out in the cold. Through the late 1920s and 1930s, contracts were landed with Marmon and notably Lincoln, as well as custom coachwork on Duesenbergs, Rolls-Royce, and other private commissions. In 1939 after failing to secure a buyer, Francis Willoughby reluctantly conceded, and everything was sold at public auction. Regitko was hired by Lincoln, where he worked on the new Continental with design legend E.T. “Bob” Gregorie.

Coachbuilding ended with the onset of unitized bodies, but the history and reverence of these pioneers is still remembered. Both Chrysler with LeBaron and Cadillac with Fleetwood recognized this, and even today bespoke coachwork is offered from Rolls-Royce and Bentley.

East Coast Coachbuilders is one of 20 classes to be featured at the 2023 Greenwich Concours d’Elegance, on June 2–4, 2023. Download the 2023 Greenwich Concours d’Elegance event program to learn more about Sunday’s other featured classes, Saturday’s Concours de Sport, our judges, sponsors, nonprofit partners, 2022 winners and more!

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

This theme – showcasing northeastern U.S. coachbuilders – should make for a great concours at Greenwich!

Lots of good looking classic cars here.

The book A Century of Automotive Style is a wonderful read on Car Design and Coachbuilders

Great article on Great cars! Well done!

So how come no mention of Inskip of Long Island? Inskip did a lovely Rolls Royce PIII that I used to drive on the weekends. Perhaps the prettiest PIII ever done.

Good article, thanks Mark and Hagerty. All these carrossiers, in addition to one-offs, produced mainly “catalog customs,” which clients would leaf through until they saw something they fancied. It was then a relatively simple matter to customize one of those to suit the client, and few in their circle would notice that their car not wholly unique.

Ralph Roberts said they pulled LeBaron out of the Manhattan phone book for its suitably snobby French sound.

Quality varied. Willoughby, Derham, LeBaron, Brunn well-built, but some houses less so, with many tacks, etc. used. Factory-bodied cars were often better built, if lacking the vaunted bespoke mien.

Of course, many custom designers wound up on Detroit payrolls.

Most of the above and other body crafters wound up doing body and fender work, minor revisions to factory bodies in the ’40s.

A small correction: in 1940 and 41 Brunn actually built a small number of town cars for Buick (not just prototypes), based on the Series 90 Limited limo body. Brunn removed the steel roof over the driver’s compartment, replacing it with a fold-back cloth top that disappeared into a compartment built into the passenger compartment’s headliner. The rest of the top was padded, rear quarter windows removed, and the rear window considerably shrunken. The rear passenger compartment was treated to higher quality upholstery and real wood trim. As the article stated, Harlow Curtice, head of Cadillac, put a stop to Buick’s adventures into Cadillac territory.

I remember seeing a ’41 on a used car lot in Fort Lauderdale, summer of 1963–for $300. It supposedly came from a Palm Beach estate, quite possible as the odometer showed only 9000-odd miles. I often wonder what became of it.

All are handsome automobiles, especially the LeBaron!