Remembering Jesse Alexander, a master of motorsport photography

Jesse Alexander, who died late last year at the age of 92, was one of the rare photographers whose mastery of his craft allowed him to elevate seemingly mundane images of the world of motorsports to the status of fine art.

Jesse spent only a handful of years following the circuit on a race-by-race basis, and at the time, he regarded his sojourns in Europe more as an adventure than the foundation of his career. Yet today, he’s universally acknowledged as one of the premier visual chroniclers of the road racing scene of the 1950s and ’60s, and he created some of the most indelible images in motorsports history.

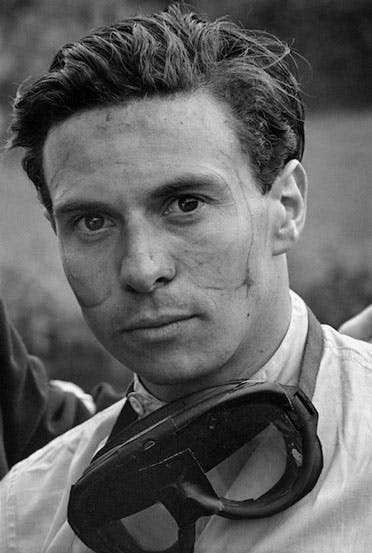

Think of Juan Manuel Fangio in a Maserati 250F at Rheims in his last Grand Prix in 1958. He’s glancing across the hairpin at Thillois to see where his competitors are, but in Jesse’s photo, he seems to be gazing back on his entire career. Then there’s Phil Hill wearing a victory garland at Monza in 1960 after becoming the first American to win a Formula 1 race. There should be elation on his face, but instead, the joy is tempered by weariness and relief—a meditation on all the obstacles he’d had overcome to achieve this long-sought goal. But most famous of all is Jesse’s haunting portrait of Jim Clark after winning the Belgian Grand Prix in 1962.

For many years, this photo was misidentified as having been shot two years earlier, when two drivers were critically injured during practice at Spa and two others killed in the race. The fact that the image actually captures Clark after his first GP win makes it even more powerful. The grime and thousand-yard stare on his handsome face are a window into the physical and emotional toll exacted by racing on a Spa-Francorchamps circuit so fast and fearsome that survival was never a given.

“The Jim Clark portrait is the only piece of film that I really knew was a major shot,” Jesse once confided over a glass of wine. “During the 1970s, when I was moving around a lot, I thought to myself, ‘I’ve always got to know where that negative is.’ I saw him on the podium after the race. I don’t know how the hell I got up there, but if you were really clever, you could scout out where the stairs were. I walked up there and said, ‘Jimmy,’ and he turned and looked over. Thank God the exposure was good. Of course, you never know until you develop the film, but I thought I had a keeper. This is the photo I’m best known for. But it all happened so easily.”

I own a print of that Jim Clark portrait, along with about a dozen of Jesse’s lesser-known photos. Seven of them are mounted on my walls. To me, they’re powerful artifacts of a heroic age I’m too young to have lived through myself. But the other reason the images mean so much to me is that they’re also mementos of a friend who—unwittingly—helped fire what turned out to be my lifelong passion for racing.

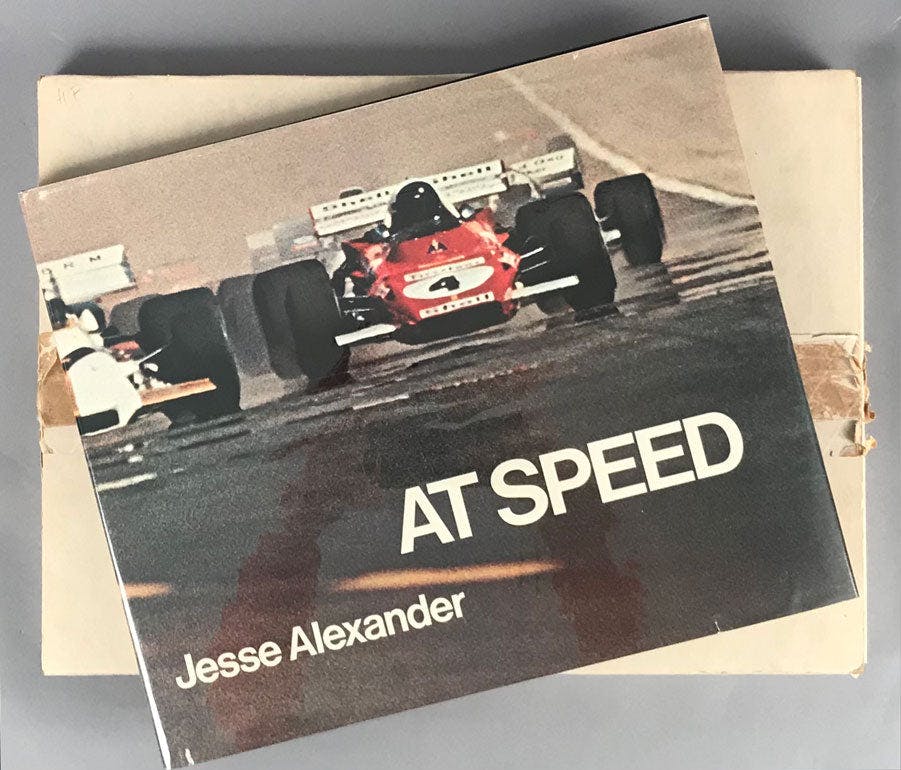

When I started following Formula 1 in the early 1970s, it wasn’t even a blip on American radar screens. At the time, the only F1 race broadcast on TV was the Monaco Grand Prix. Naturally, I devoured the race reports in AutoWeek and Road & Track, but the former came on cheap newsprint, while the latter was limited to black-and-white photos. The racing seemed distant, alien and, above all, monochromatic. Then, for my 16th birthday, my parents presented me with a book, At Speed, by somebody named Jesse Alexander.

Now that coffee-table books printed on heavy stock are so commonplace that they often end up in remaindered bins, it’s almost impossible to appreciate the impact At Speed had on me. To begin with, the book was gigantic—14.25 inches tall and 17 inches wide—and it was filled with arresting images that brought big-time motor racing, circa 1971, to life in luscious, eye-popping color. Here was the glamour, the speed, the exhilaration, the tension, the technology, the wrecks, the players, the fans. The captions were minimal, but who cared? The photos weren’t record shots taken to preserve history. They were explosions of colors that celebrated and glorified a sport unlike any other.

Jesse was remarkably self-effacing about his work, and he insisted that he didn’t deserve much credit for At Speed. “It was the idea of Jon Thompson at Road & Track,” he once told me. “Road & Track hired this Scandinavian book designer, and he was determined to make it a huge, coffee table thing. I just went along for the ride.” But what a ride!

Expect to pay more than $1000 if you can find a copy in good condition. Mine has been trashed. The cover is shredded. The spine is shattered. Some of the pages have been damaged; believe it or not, I traced drawings off the originals. No matter. I still get a jolt every time I open the book and see the close-up of a Surtees TS9 front suspension, the panning shot of Emerson Fittipaldi in a Lotus 56B turbine car, the impossibly blue eyes of François Cevert peering out from a pockmarked Bell helmet. And whenever I look at the four-frame sequence of the start of the French Grand Prix, with the cars growing ever larger and sharper, I swear I can hear snarling V-8s and shrieking V-12s getting louder and more insistent.

Twenty years passed before I finally met Jesse. I was writing a book about the Scarab race cars of Lance Reventlow, and I needed photos of the F1 cars racing in Europe in 1960. Jesse invited me out to his studio near Santa Barbara, where he and his wife, Nancy, had settled. This was long before he’d digitized and cataloged his images, so we spent hours poring over film negatives and contact sheets with jeweler’s loupes.

Chuck Daigh had told me about driving the Scarab at Spa around what he described as “the scariest corner in the world”—the high-speed right-hander known as Stavelot. A bump at the apex would unsettle the car so badly, Daigh recalled, that the marshal started throwing the yellow flag before Daigh arrived at the corner. Jesse found several photos of the Scarab with its right-front wheel flapping in the air like a sprint car at Terre Haute. And sure enough, there was the marshal, with a death grip on the yellow flag. I could have kissed Jesse.

We worked together on a few other projects over the years, and I saw him semi-regularly at races, car shows, art galleries and media events until he stopped making the drive in to Los Angeles. I always relished the opportunity to hear him tell tales of his days in Europe, living in a chalet in Switzerland and gamboling around the continent in a VW Microbus, then a Porsche 356 and finally a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL—the very chassis, he discovered later, that had been driven to victory at Le Mans in 1952. But Jesse wasn’t one of those characters who dine out endlessly on their old exploits. He was always interested in the here and now and what came next, whether politics or advances in digital photography or gossip about the current racing scene.

Jesse was a gentleman with a gentle soul. Gracious and cultured, he was generous with his time, help and praise. A few years ago, I was honored to serve as a talking head in a documentary about his life and work. In it, I bloviated at embarrassing length about a personal fave—a sumptuous color photo Jesse had taken with a Rolleiflex twin lens reflex camera of Alberto Ascari in a Lancia D50 at the Gasworks Hairpin during an early-morning practice session at Monaco in 1955. A week later, a signed print materialized on my doorstep.

Unlike artists who prattle on endlessly about their aesthetic choices, Jesse was relatively reticent about his work; he preferred to let it speak for itself. In general, he subscribed to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s dictum that a photograph should capture the “decisive moment”—that is to say, embody the essence of an event. When I asked him to describe his personal philosophy, he said simply, “The operative word, when you talk about my work, is emotion.”

Jesse himself was an unflappable figure. I can see him now, in my mind’s eye, an oasis of bemused calm among the frenetic activity at the racetrack. He’s wearing khaki pants, a button-down shirt and a photo vest, with a camera or two draped over his shoulder. On his face is the wry smile of a man who took life as it came—and froze it for posterity with a click of a shutter.

Godspeed, Jesse.

Great article. I just recently learned of Jesse’s passing and am happy I was able to have a few brief email encounters with him back in the early 2010s about his photography. I was fortunate to come across a tattered, yet fully intact “At Speed” maybe 6-7 years ago and snatched it up immediately. The Francois Cevert photo always chokes me up, such a young racer with much more to share with us and taken all to quickly.