Owning One Lagonda Takes Patience. 11 Takes Lifelong Love

Dimitri Labis is a man of apparent contradictions. He’s Belgian but has made a living out of distributing artisan Italian foodstuffs rather than his nation’s beer or moules-frites and waffles. And when it comes to cars, his head isn’t turned by marques from neighboring France—Alpine, Bugatti, Peugeot, or Citroën—but, with one or two exceptions, by British brands, and one model in particular: the Aston Martin Lagonda.

The 56-year-old Labis owns 11 of the things, the otherworldly vision of the future that was launched at the 1976 Earls Court Motor Show and chimed with the world’s wealthiest drivers during an age when computing and science fiction were dominating culture. Does anyone, anywhere in the world, own more Lagondas? That’s the question I put forth when we meet at a barn housing some of his cars in the Kentish countryside. “Only Rodger Dudding,” comes the reply. Dudding, he tells me had amassed 24 of them over the past 15-odd years, including a rare Lagonda Tickford he bought from Labis.

Labis’ love for the Lagonda grew out of a love for London. As a boy, he was obsessed with London. The only problem was, Labis lived in Mouscron. Our capital city and his provincial Belgian village are separated by 160 miles of land and 27 nautical miles of English Channel.

Such things were minor obstacles to the strong-willed youngster. And, as it was 1982, his parents were quite content to let him gather up his pocket money, buy a ferry ticket, pack a bag, and make his way to Calais, take a two-hour boat trip to Dover, and then rattle up the train tracks from Dover Priory to Charing Cross. Once in London, he would buy a Travelcard and jump on the top deck of a double-decker, sitting in the front row with an A–Z street map in his hands as the city landmarks passed him by.

“Those were the days,” says Labis. “I was only 14, but my parents would let me go. It was quite a trek. I’ve always been attracted by Britain, from an early age,” says the self-confessed Anglophile. It was during one of those trips that he spotted a car that would capture his heart every bit as much as Britain’s red telephone box (Labis admired our nation’s old phone boxes so much he bought one, 15 years ago, and took it back to Belgium so he could install it outside his home). And the car? An Aston Martin Lagonda.

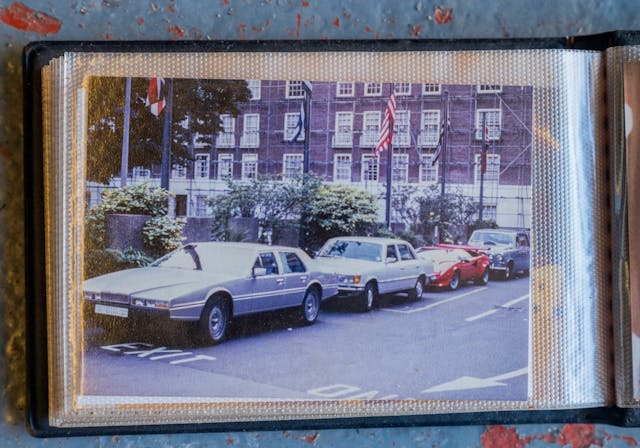

He still has a photograph of that moment, captured on 35mm film outside the front of Knightsbridge Park Tower Hotel, on the edge of London’s Hyde Park. In the photo there’s a silver, early Aston Martin Lagonda Series 2, a car that makes the Mercedes 450 SEL behind it look like a pauper’s jalopy, and behind that is a kinky boots–red Lamborghini Countach, its optional rear wing obscuring the Daimler DS limousine at the end of the parking bay. Taken at a time of historically high unemployment rates and painful inflation rates, the photo is a stark snapshot of the haves and have-nots.

During those London bus tours, Labis would jump off at stops to drink in the stock of some of London’s most exotic car dealerships. One of those was P.J. Fischer, a Bentley and Rolls-Royce specialist in Putney that was run by Peter Fischer, a wealthy Swiss car enthusiast whose warm welcome would prove to be an influence on the young Belgian stranger who meekly stepped into the showroom.

“I like the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud, like the one that’s at the back there,” says Labis, gesturing to the car in the corner of the barn where some of his cars are stored. “I remember going to look at the cars, and he was the first dealer who invited me to sit in the Rolls. I said, ‘I don’t want to be trouble—you know, I’m not a potential buyer.’ Of course, he knew it and then he let me sit in there, and it meant a lot to me.”

Another favorite haunt was Straight Eight, on the Goldhawk Road in Shepherd’s Bush. The former classic car dealer was popular with well-heeled car enthusiasts. Its proprietor, Daniel Donovan, would have a trickle of Lagondas in the showroom, and young Labis couldn’t get enough of them. “I would look in the back of the classic car magazines, see which dealers were advertising Lagondas, and I would go around all of them traveling on the double-decker!”

Fast forward to 2005, and after a handful of successful years with his business, Labis bought his first Aston Martin, a 1971 DBS V8 automatic—“a cheap car that was on eBay, but it means a lot to me as my first Aston Martin.” Predictably, he didn’t stop there.

There followed a botched eBay purchase of a V8 Volante where, despite winning the auction, Labis was gazumped by a U.S. dealer. By way of consolation, he bought a glamorous Rolls-Royce Corniche from a dealer in, appropriately, the equally glamorous Beverley Hills. But that car didn’t seem to go down well with him or his fellow countrymen. “I am fair-headed so I would be driving it with the top raised on a hot day. But you can’t drive them on the continent without being insulted—people insult you, spit at you even. They’re all communists,” jokes Labis.

Finally, in 2007, he summoned the courage to meet his hero and bought his first Lagonda, also on eBay. Was he, I wonder, fully informed about the potential pitfalls that can come with Lagonda ownership? “I had been told, and I had been to see many. But I didn’t care, I just wanted one. But I must admit I learned from my mistakes with that car. It was a UK car and had many corrosion issues. After that, I knew more about what to look for.”

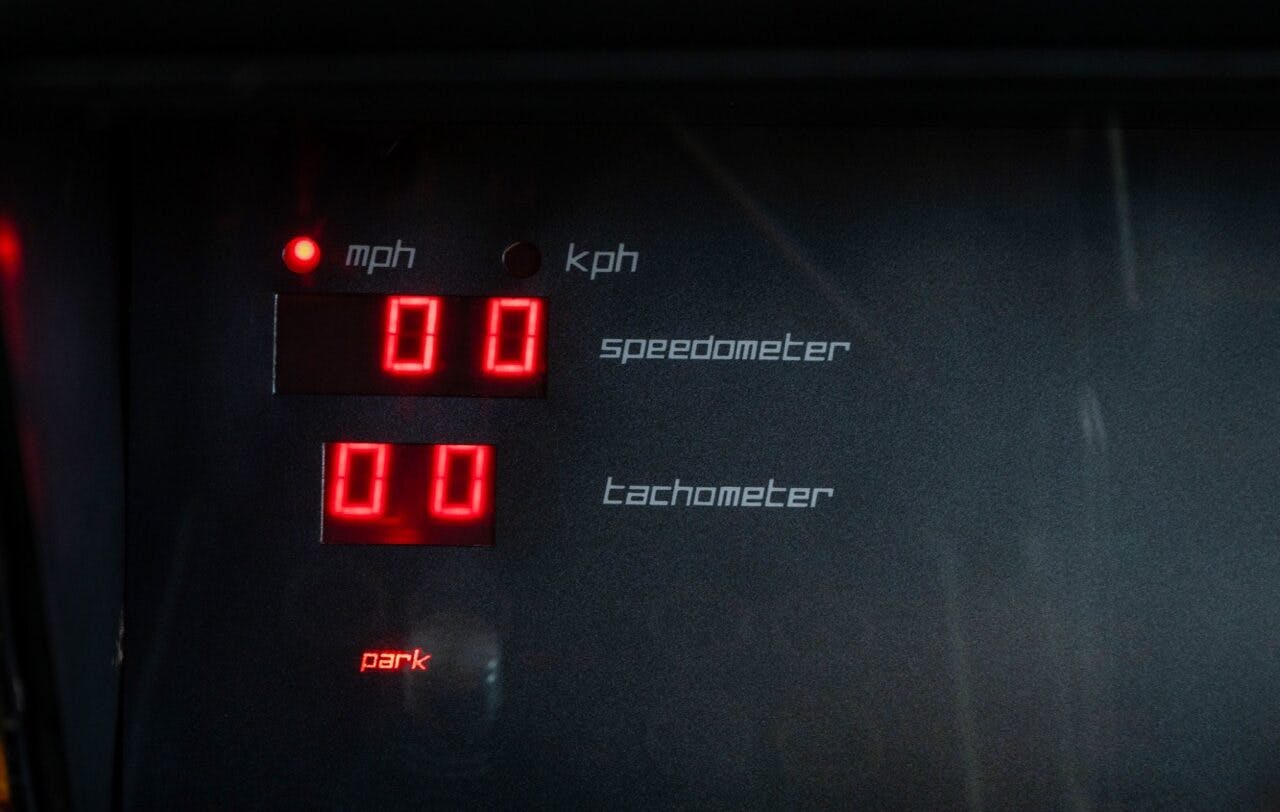

Next came a late Series 2 example with the infamous cathode ray tube (CRT) instruments, bought at a Bonhams auction in 2008 after being listed by a former chairman of the Aston Martin Owners Club (AMOC) “because his wife hated it.” The CRT instruments weren’t working, which I suggest must have gone in his favor then, given few people were prepared to risk taking on a troublesome Lagonda. All in, he paid a mere £11,000 for what in 1979 had been the world’s second-most expensive car, at £50,000 (topped only by the Rolls-Royce Camargue), by the time the hand-built saloon reached customers.

The three-year delay between the car’s unveiling, in 1976 (just under a year after the Lotus Esprit), and when it began rolling off the production line can be attributed to one thing: ambition. At the time of its conception, designer William Towns and engineer Michael Loasby were given instructions to build the world’s most advanced saloon car—and, under the orders of Peter Sprague, who led a consortium that bought an ailing Aston Martin in ’75, it should feature electronic instruments.

Sprague, an American, was chairman of National Semiconductor in the U.S. and took Loasby to visit the company’s HQ in California. Loasby was impressed. In 1976, he told Electronics & Power magazine that he viewed the system as something Aston Martin could sell as a package in the future.

During prototyping, Fotherby Willis Electronics, based in Leeds, was to develop the LED digital instruments, but financial problems saw the baton handed to the Cranfield Institute of Technology. The change failed to solve the problem, however, as Loasby recalled in the 2007 book, Aston Martin: Power, Beauty and Soul, by David Dowsey: “You should never get any academic on anything because they will never finish the job and they will never get it to work. Cranfield made a fearful mess of the electronics because, even though they were at the forefront of technology, they had no idea of the realities of what you could or couldn’t do in a car.”

Sprague agrees. Speaking with the AMOC in 2021, he said, “We didn’t explain clearly enough what we needed to accomplish. It was very early, but we ended up with a cable harness the thickness of your wrist, when it could have been three wires.” During that development period, remembers Sprague, things were touch and go for the company, and every deposit taken for the Lagonda kept the company afloat. “I would get there on a Wednesday, we couldn’t make the payroll, we’d sell a Lagonda on a Thursday and we made the payroll.” (Five years after deliveries began, the LED dials were replaced with more reliable CRT instruments. However, the flaw of both systems becomes apparent as soon as sun shines onto the instruments.)

That second Lagonda with its failed instruments marked the beginning of a steep learning curve for Labis, who confesses to having mechanical skills limited to tasks as simple as changing a set of spark plugs. He began hunting for the tiny number of specialists who could be entrusted with a Lagonda and, importantly, deliver on their promise. “I sent it to David Marks, the CRT specialist in Nottingham, and had the dash fixed. It has been working ever since.” That was 16 years ago, testament to the skills of the team at David Marks Garages, who are perhaps best known for their work on cars owned by the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust, including William Lyons’ personal Jaguar XJ6.

Labis’ next Lagonda arrived in 2010, and another fell into his lap a year later after he helped out a friend who had been unlucky in a business venture. He went on to give that friend work, repairing the sills which, he says, had been previously repaired by the factory but “they did it the way they originally came out of the factory, without any rustproofing, so eight years later they were completely holed!”

From there his collection of Lagondas kept growing, including a rare long-wheelbase Tickford model that he acquired in 2014 and would later sell to Rodger Dudding. Pinpointing the motivation to own these cars, however, is difficult. Was he hoping to amass this many? Was there a long-term plan? “I know it doesn’t make sense to have 11 identical cars in a collection, but I just love them, and I have got to know them. I suppose originally there was a little bit of an ‘investment’ idea behind it, but the longer you keep them the more you spend on them to keep them maintained and fully working, because they were designed to be driven, so the investment potential is questionable.”

There’s no doubt that the Lagonda is back in fashion. Wedge cars of the 1970s and ’80s are in vogue, being snapped up by buyers like Labis who grew up gazing longingly at reviews in magazines and hoping to spot one in the wild. He agrees that the car is having a moment. “It stunned the world at the Earls Court Motor Show in October ’76 and it still has that wow factor today.”

That wow factor comes from the single-minded vision of William Towns and the clever packaging of Michael Loasby, meaning this four-seat, front-engined luxury saloon with a generously sized boot stands a mere nine inches taller than a contemporary Lamborghini Countach.

Needless to say, such architecture brings compromises. Open a back door and even before attempting to settle on the back seat you can see what a challenge it will be to squeeze through the tiny aperture. Sure enough, legroom is stingy and headroom is, well, dire. I’m under six foot and my head well and truly presses into the roof. All the more reason to tilt your head toward the Panasonic television and video cassette player, which are somehow squeezed between the front seats.

The front of the cabin is considerably better at accommodating people. Early cars had touch-sensitive “membrane” switchgear flanking both sides of the steering column and controlling the function of the lights, heating element, clock, bonnet release, both fuel filler covers, and the cruise control system. Small beveled knobs took care of the wipers, instrument dimmer, and temperature control. To this day the aesthetic feels novel and innovative. Later cars moved to plastic rocker switchgear that may be more reliable but doesn’t capture the zeitgeist of the 1970s.

Labis is full of praise for the Lagonda’s “fantastic” driving experience, saying they make great GTs that “cruise comfortably at 100 mph.” Hidden beneath the hand-beaten aluminum bodywork are the 5.3-liter, 230-bhp (227-hp) V-8 and three-speed automatic GM gearbox that make the 4542-pound saloon a 150-mph car. He reckons on an average fuel consumption of 20 mpg, has driven as far as Davos, in Switzerland. The stability and comfort are outstanding, he says, so much so that he has even slept in one in the past. The only drawback is the length of the car and its poor turning circle.

As for the community of fellow owners, for Labis it is one of the main attractions. He and his wife spend weekends enjoying road trips with fellow Lagonda devotees. Given only 631 were ever sold before production ended in 1990, and so many have disappeared off the face of this earth, is there, I wonder, a special handshake amongst this exclusive club? “A special handshake? Well, there is a song, the Lagonda lover song. I can get you a copy.” Is it clean? “It’s printable,” laughs Labis.

Wherever he goes in one of the cars, people inevitably ask what it is. And for those who do know, surely they question Labis’ obsession with the quirky British luxury car. “You have to be a little bit eccentric to own these cars,” he says.

Eccentric or not, the car is no laughing stock where Aston Martin’s history is concerned. It saved the company from total ruin, and the men behind it—Towns, Loasby, and Sprague—somehow pulled it off against appalling odds.

Perhaps it is Sprague who best approximates why it is that people like Dimitri Labis have a lifelong fascination with this most peculiar of Aston Martins. When asked whether there was a business plan backed by market research, Sprague explained it was as good as built on faith: “Basically we looked at William Towns’ extraordinary drawings, and we asked Mike Loasby if he and his team could build it. They said yes. We had confidence in the team. It was comparable to building the Spitfire during the Battle of Britain.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Great story, James! Honestly, Labis’ story is probably as interesting if not more than that of the cars themselves. Especially the part about the photo of the first one he saw. I have a Polaroid of me by the Lancia Stratos Zero at a NY car show. It’s always fun to be able to pinpoint exactly when an obsession started.