Neutron Engines’ Honda-based K48 V-8 promises to be a pint-sized screamer

Evidence of mechanical evolution litters the house of mechanical engineer Craig Williams. An eviscerated Honda K24 sits next to his desk. Prototype fixtures pile in each corner and cubby. The apparent chaos has a focus: the K48, Williams’ one-off design for a V-8 based upon Honda’s DOHC K-series four-cylinder. What Williams didn’t realize when he began this project five years ago, though, was that his ambition would become a form of creative therapy that would sustain him through a sudden onset of chronic lung disease.

Before his life pulled him towards an unknown fork in the road, Williams was simply a gearhead day-dreaming up the perfect supercar project. “I was inspired by John Hartley’s V-8,” he says. “Me being an engineer, I was like, that’s the coolest thing I’ve ever seen. I wanna do something like that.”

Williams initially imagined creating a new flat-12 for a Ferrari Testarossa. Though the car will forever be remembered for its edgy styling and 12-cylinder symphony, the engineering beneath that cutting-edge wedge left a lot to be desired for the 21st-century engineer. Williams envisioned a block that utilized BMW E46 M3 heads with a Bentley crank, but his initial bravado was checked when he began to evaluate the cost and the groundwork involved in designing and actually producing his dream flat-12.

“I was so ignorant. I started looking at it, and then I realized the machine I would need to build this engine would be big, and this would be really expensive, and boxer engines have a couple of things that are a little tricky to design about them. So I decided, I’m gonna go cheaper in the realm of designing my own engine and do the V-8. That’s how I ended up with going with the Honda.”

Williams wasn’t immediately sure which Honda powerplant was the right candidate. He looked at other Honda platforms, such as the S2000’s F20, and even at Mitsubishi’s venerable 4G63: “But that’s like a turbocharged engine designed around a cast-iron block. I felt like a Honda cylinder head for a naturally aspirated build was a better choice, and so then it became a choice between the F20 or the K-series.” Since the F20 would suffer from the “S2K tax” levied on parts for the low-production coupe, Williams chose the humble K-series as an organ donor.

The K-series carried the bulk of Honda’s lineup from 2001 through 2012. The engines came in two flavors: a short-deck K20 and a tall-deck K24. The latter was tailored for heavier duty applications, with a longer stroke to churn more low-end torque. A K-series was more common and accessible than an F20 and thus promised to save Williams time and money.

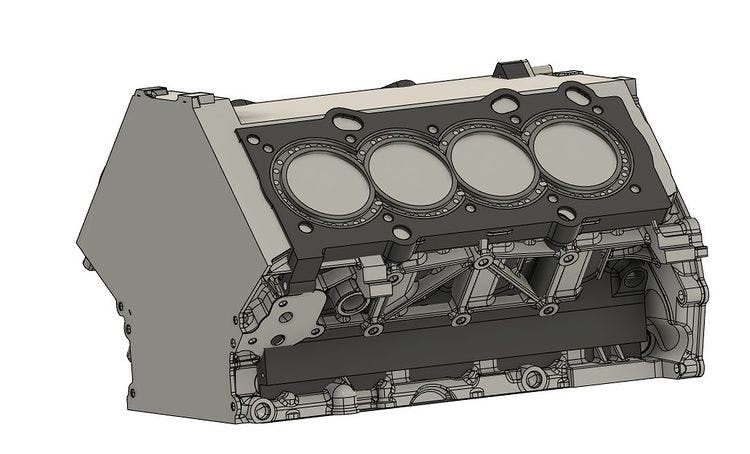

By using the K24 cylinder heads, Williams saved himself the time-consuming labor of developing and producing the most complicated component in an engine. Sneaking Honda’s homework allowed him to focus instead on feeding those cylinder heads with the coolant, oil, and rotational power from the crankshaft’s timing gear with his custom-designed engine block. Most of that work roughed into shape rather quickly: He built the internal structures and oil ports to support the crankshaft, designed the block’s deck surface where the K24 cylinder heads would mate, and roughed out its external contours. Once Williams began to build the timing chains, however, the decision to use stock cylinder heads bit him.

View this post on Instagram

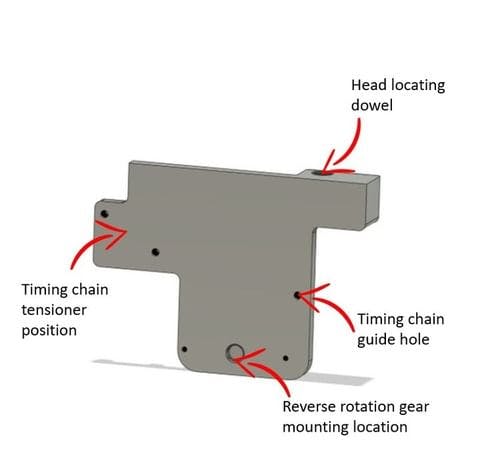

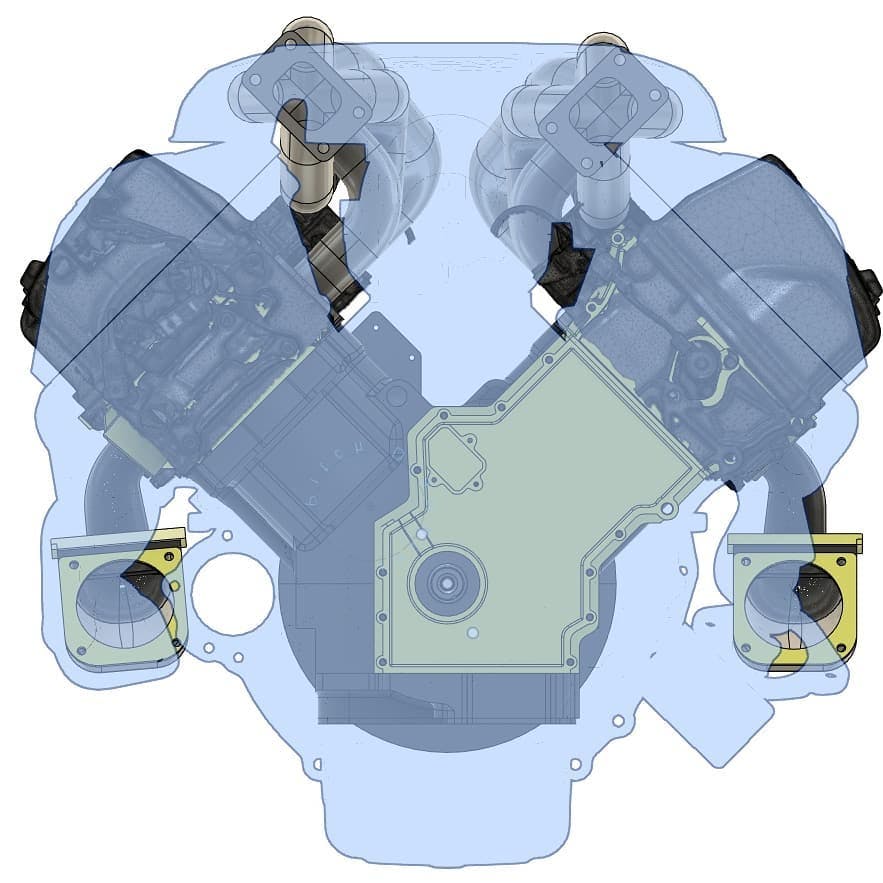

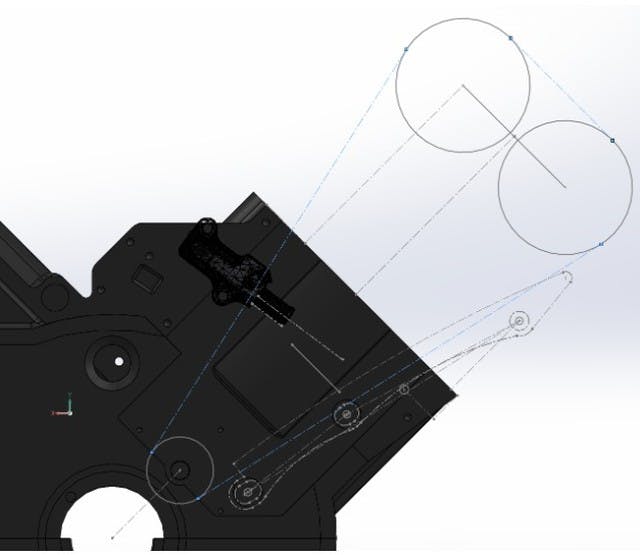

Hang on, you may be thinking. Why multiple timing chains? In short, because it’s simpler and more affordable. Williams didn’t want to mirror a stock head into reserve-flowing the air-charge with custom cams. By flipping the opposite head backwards and adding a second timing chain, he could use a factory head on either side of the engine without making any modifications, since the intake and exhaust ports on each bank of cylinders would face in the same direction. A second timing chain didn’t solve everything, though.

In the conventional downdraft cylinder-head configuration, the intake ports face the valley of the block. When Williams mocked up the design in CAD, he discovered that the second timing chain’s hydraulic tensioner interfered with the internal geometry of the block. It rested on the parting line of the K24’s main girdle, putting stress on a relatively weak area of the block. Even worse, the bolts for the tensioner clashed with the main bearing bolts inside the block.

“Then I flipped it and put it in the hot-V configuration, and that moved the timing-chain tensioner right into the middle of the V, which is really nice. It’s basically on my main oil gallery, so I just drill a hole straight through and it’s being pumped directly from that main gallery-like factory.” He effectively swapped the locations of the intake and exhaust cams so that the tensioner moved to the other side of the timing chains, placing it in a much more convenient area of the block.

The other area that challenged him was the rotating assembly. Taming the notorious harmonics of the flat-plane crank became something of a Sisyphean engineering project—”really tricky,” in Williams’ words. He wasn’t building just any flat-plane-crank mill, either; the K-24 carries a stock stroke of 99 mm. For comparison, the Voodoo in the Shelby GT350, the largest-displacement flat-plane-crank engine produced, uses a 93-mm stroke. The difference was only 6 mm—roughly a quarter of an inch—but the implications were outsized.

Second-order vibrations are induced by the horizontal movement of the rod acting in harmony with the usual vibrations induced by each piston and rod traveling up and down their bores. With a traditional cross-plane V-8, the 90-degree firing order produces fewer second-order vibrations because the rods counteract their own movement every quarter-turn of the crankshaft. When you flatten the crank journals into a 180-degree firing order, that counteraction only happens every half-turn, and second-order vibrations build during an ignition event because there isn’t a rod acting in time to balance the rotational forces. The critical strategy in flat-plane designs, then, involves reducing the weight of the rotating assembly to minimize inertia generated from the bottom end of the engine, and this usually results in the short-stroke, small-displacement V-8s produced by the likes of Ferrari.

“Just for comparison, the Voodoo pistons are 400 grams, with the piston pins at 91 grams. Its rods are 611 grams. In my engine, my pistons are kind of like drag pistons without vertical gas ports—only lateral ones—and are custom ones I designed,” Williams says. “They only weigh around 265 grams [each], with a 77-gram piston pin. My rods are titanium, and right now they are at 374 grams each— about a third of the weight cut out of the Voodoo engine.”

The crankshaft and rods must be custom-machined not only to save weight but also to ensure that the components can handle the stress. Each rod utilizes the rod bearing from the Lamborghini Gallardo’s V-10 and the wrist-pin journal from Honda’s J35 V-6. The rods, which will be custom-machined by Saenz Performance, are also slightly longer, with the wrist pin’s position in the piston raised closer to the crown. This creates creates a small reduction to the rod angle as it swings with the crank’s rotation, reducing second-order vibrations by another 4 percent. After working out the pieces, Williams sent his crankshaft design over to Arrow Precision in the U.K., and the company keyed up a few changes of its own along the way to guarantee that the one-off piece could handle the harmonic stresses of the flat-plane configuration.

The last major challenge Williams faced was how to design the internal passages to allow for water jackets around the cylinders. With custom billet blocks, the difficulty in doing a “wet” block with coolant passages involves getting the CNC’s tooling inside the block without having massive access plates that create structural holes in the blocks and introduce more sealing surfaces (read: potential leaks). Most billet blocks are found in high-power applications, like drag racing, in which long run times or traffic-capable cooling aren’t on the engine’s to-do list; but Williams needed his K48 to be streetable. After researching his options, he settled on Dart’s mid-sleeves, which are typically inserted into an engine block to replace its original cylinder walls with reinforced sleeves. Williams saw that Dart’s mid-sleeves could be used as the inner wall of the water jackets while the custom block was overbored to create a space between it and the sleeve for coolant to flow. This insight was key to getting the project out of CAD and into real life, because it eliminated the need for even more expensive cast block or an overly-complicated billet block.

The Neutron Engines K48, as Williams has dubbed his venture, will end up with a slightly larger, 90-mm bore and the stock 99-mm stroke, giving it a displacement of 5.0 liters once all is said and done. As a quad-cam V-8 around the 5.0-liter figure, the K48 gets a lot of internet comparisons to Ford’s Coyote. Williams actually owns the 5.2-liter Voodoo, itself a derivative of the 5.0-liter Coyote long-block; the engine sits in the nose of his Shelby GT350. However, his K48 is much slimmer than the Coyote, especially where it matters—down at the block skirt, where frame rail clearance becomes a factor.

“I would say, for the most part, the engine is my crown jewel,” Williams says. “It’s what I spend all my money on and all of that, but I have a couple of cars in mind for what I would like to swap it into.” Only time will prove which vehicle is the first to receive a K48 swap, but Williams imagines his engine powering everything from a 997 Porsche 911 to a Lotus Esprit.

Williams started the project five years ago, but he was ultimately spurred to complete the design after he was diagnosed with bronchiectasis, a disease in which the lung’s airways are permanently damaged. For two hours each day, he was forced to sit in a chair hooked up to a machine that administered a breathing treatment.

Williams realized he could bring the breathing machine into his office, and he used the time to work on his engine. “That’s when my project really accelerated, even though I got this really awful condition. It gave me the time, it forced me to make a concerted effort.

“[Designing the engine] has been a wonderful outlet for me.”

The time spent in front of the computer, hooked up to the breathing treatment, became its own cathartic therapy. Unexpected health issues never arise without taking their toll on someone’s spirit, but the K48 helped spin Williams’ seemingly constraining downtime into creative productivity. Every day, for those two hours, he’d boot up Fusion 360 and begin reverse-engineering the components he needed to put together. “That is exactly why I did this,” he says. “I wanted to keep my passion alive, and I enjoy cars.”

Williams expects to have his prototype assembled by the end of this year, barring any pandemic-related delays with suppliers. With a goal of 10,000 rpm and over 700 hp, the K48 should be a real screamer for its pint-sized package. Plus, that hot-V configuration is begging for a tightly-packaged turbocharger combo—and Williams has that very madness in mind.

This is very interesting. I have a k20 myself and I always wondered if there was a k-series engine out there, then I found this. I’m just hoping this engine comes into production because this will be an amazing engine to have.

It IS impressive, but if he LIKED 12s, WHY didn’t he cut-up TWO of his new V-8 engines, to “3-D” a 60-degree V-12 of 7.5L? Now, THAT would be an engine for the “Ages”. You’re thinking, Euro-motor sports won’t certify an engine SO large, but Screwl-them, –design a V-12 for 3/4-full scale WWII “Warbird Replica”-Hobbists. 1500-2000HP in an all-alloy full-scale Replica, could translate into Ju-87G “Stukas”, Heinkle-He-IIIs & 219 UHUs, long-nose Ta-152s, P-51s & 40s-with-POWER, K-61s, and of Course, Hurricanes, Spits, Seafires. The Ferrari “flat-12” was a FRIGHT-mare to OWN, because Ferrari was So Stupid, the 348 Testa-Rosa needed to drop the engine out the bottom for a “Service”,–a horrible WA$TE of over $1500.00, before a single wrench/spanner was turned-on-the-Tune!

This is a dream come true. I want 2 of them please.