Georgia engine builder challenges Porsche dogma with hot-rod 996s

Jake Raby likes problems. If you manage to catch him amidst a rare moment of rest, he’ll cheerfully tell you that the quicker things blow up, the better. “I like failure. I like when things don’t work,” he explained during our visit to Flat-Six Innovations in Cleveland, Georgia. “You never learn from successes. Honestly, success hinders development because it makes you think you know more than you do.”

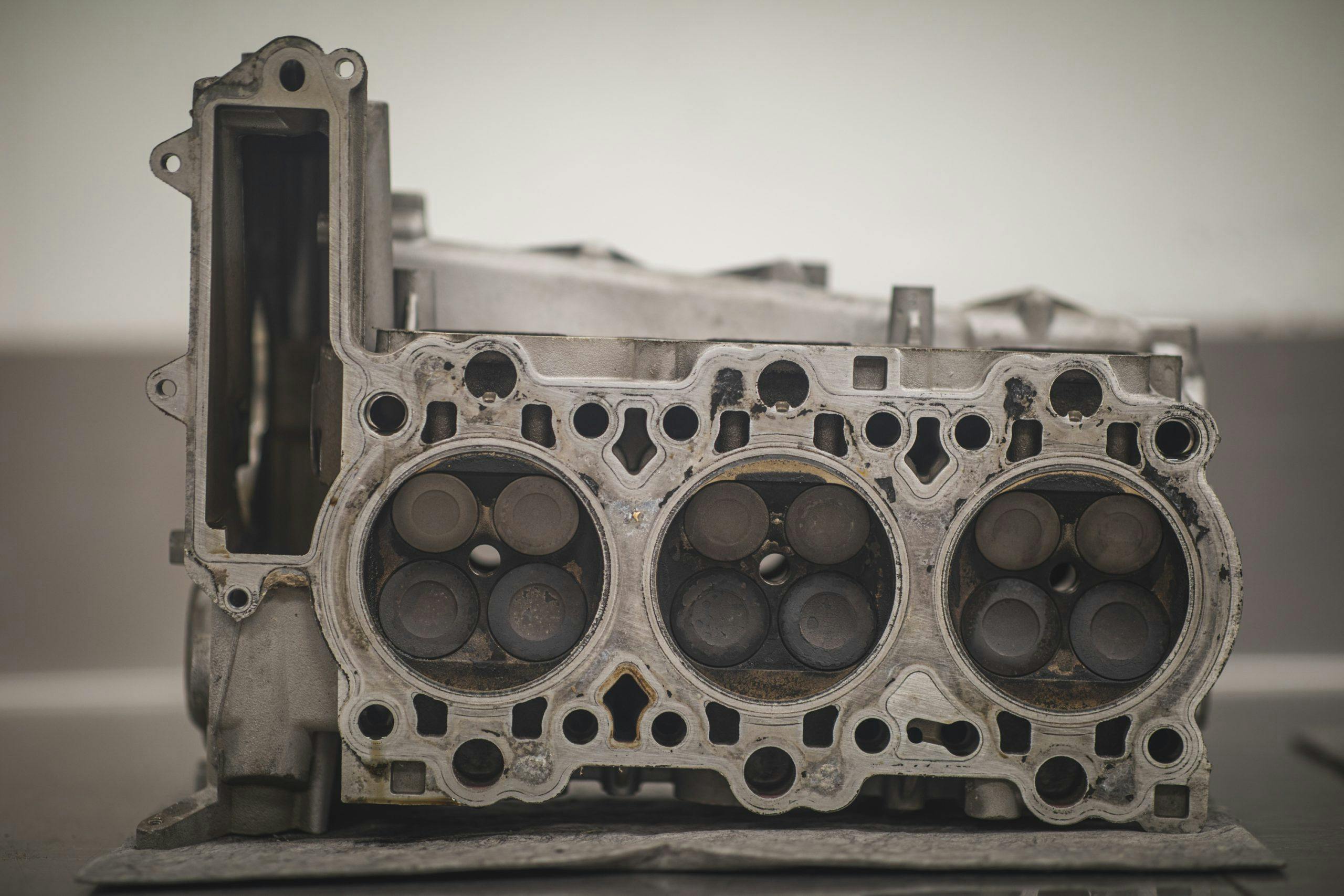

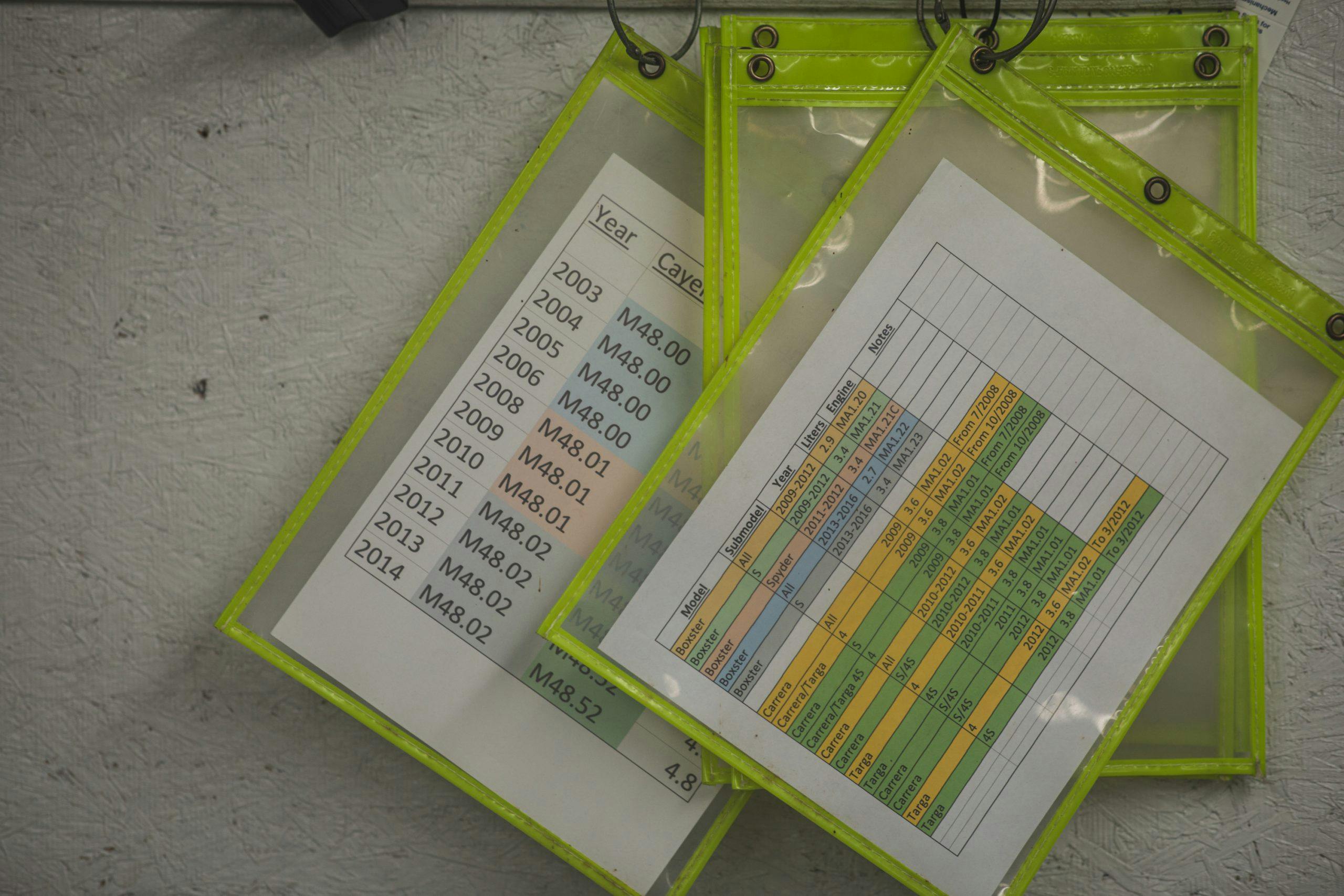

Perhaps that’s why Raby has chosen to become an expert (although he disavows that word) in the much-maligned water-cooled M96 and M97 engines that powered the 996- and 997- generation (1999–2013) 911, as well as Boxsters and Caymans of that era. Raby developed the original patented repair for the most notorious issue on early water-cooled (M96- and M97-engine) Porsches—intermediate shaft bearing failure—but his “fixes” go much further, into hot-rod territory. They also turn on its head the bottom-line-oriented thinking that propelled Porsche’s first truly mass-produced 911.

Raby himself turns on its head whatever preconceived notion you might have of a master Porsche engine builder. A proud Marine veteran, his office appears more like a recruiter’s den than the administrative haunt of a master engineer. There are no pictures of cars, no signed, well-wishing headshots from assorted automotive celebrities, and no framed feature articles nailed to the walls. Instead, a carved seal of the Marine Corps. hangs on the wall a few feet from a stuffed bobcat he bagged on this property. In the corner, a lone shotgun rests in a glass-fronted gun cabinet, downwind from a small paper sign warning that anyone attempting to haggle or negotiate a quote or invoice will be immediately denied service and physically removed from his 20-acre property.

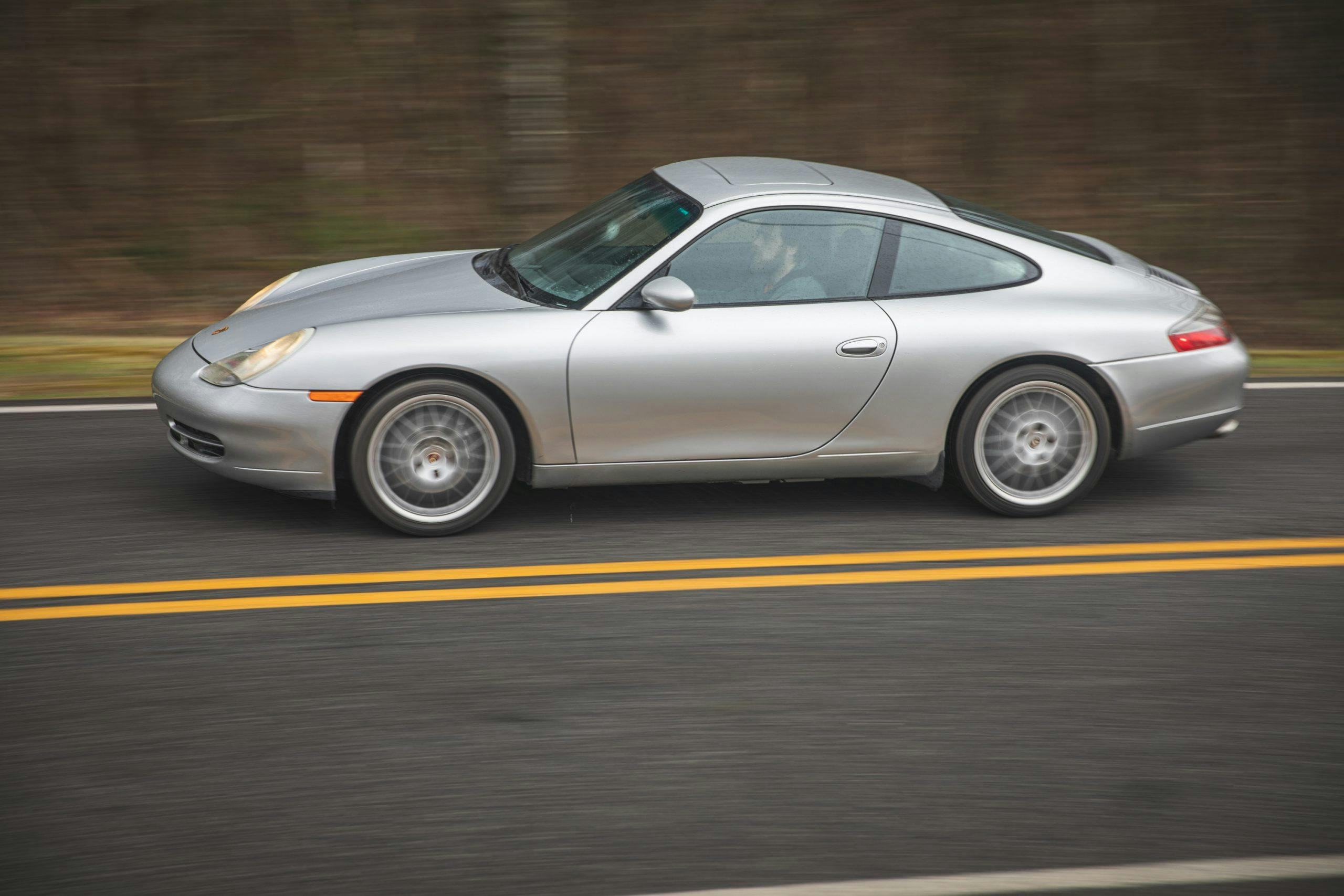

Those who patronize Flat Six Innovations (FSI) each year are an unconventional bunch for Porsche nuts, themselves. Whereas most high-end Porsche shops park rows of gleaming, fully-prepped hot-rod 911s, the customer car storage area of FSI hides a generic fleet of basic, world-worn 996/997 coupes and cabrios complemented by a smattering of equally unremarkable Boxsters and Caymans. Outside of Raby’s idyllic tree-lined workshop, water-cooled Porsches like these are still among the least likely candidates for big-buck modifications. The typical driver-condition 996 still trades for an average of $29,000 according to the Hagerty Price Guide. If you hand Raby the keys to your 986 Boxster, you’re particularly mad—our price guide indicates a 2000 Boxster shuffles around for an average of $11,000. Raby’s services can easily run triple these values and beyond, and that’s accounting for the recent run-up in values for water-cooled Porsches. Still, starry-eyed enthusiasts from around the world made the pilgrimage to Cleveland, Georgia long before prices jumped.

“These guys would bring in a broken 996 or a Boxster, and it would still be their dream car. I still hear that on a weekly basis—‘dream car,’” says Raby of his early customers. “I would tell them they would have to love this $5000 car beyond measure for me to do what you want me to do.”

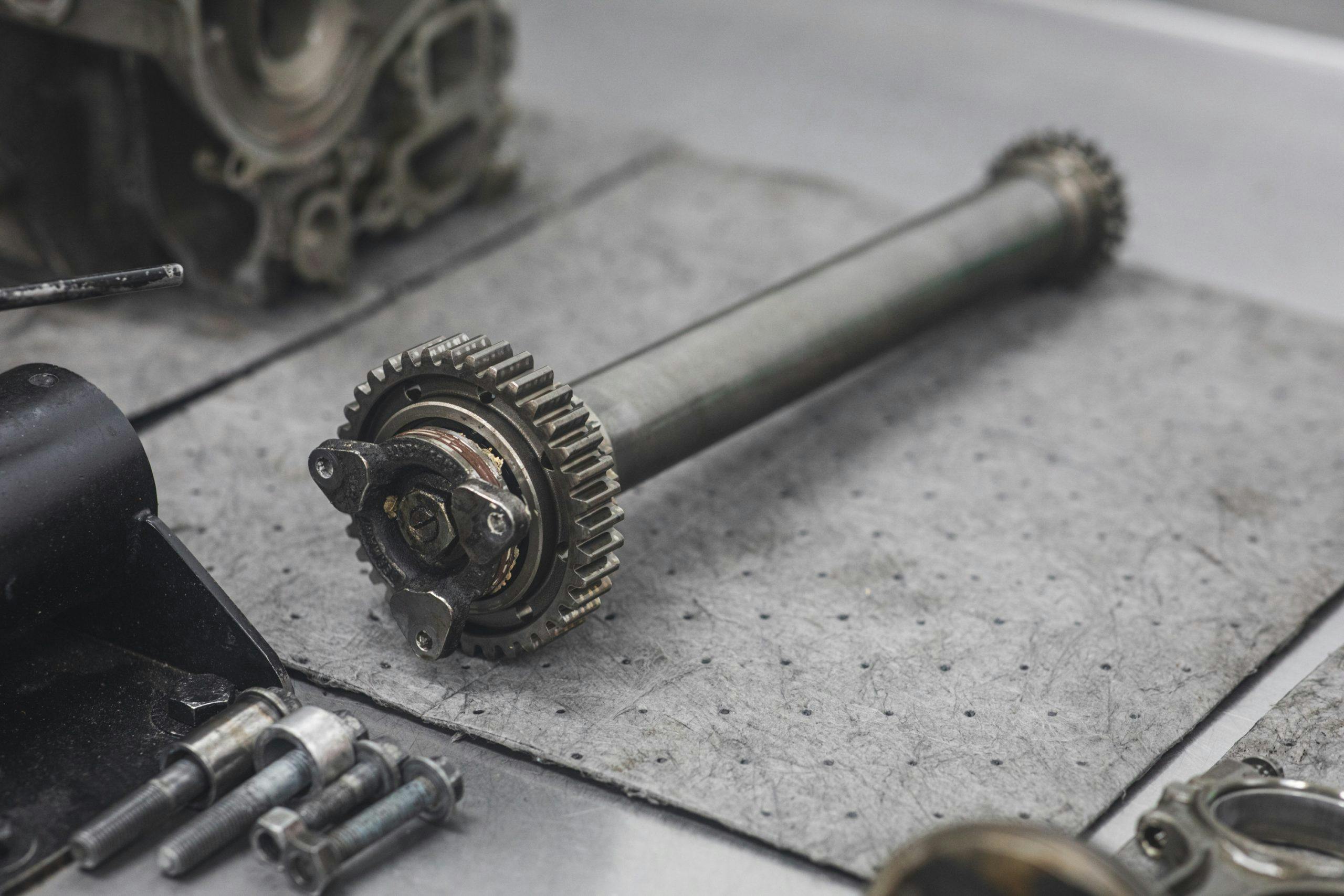

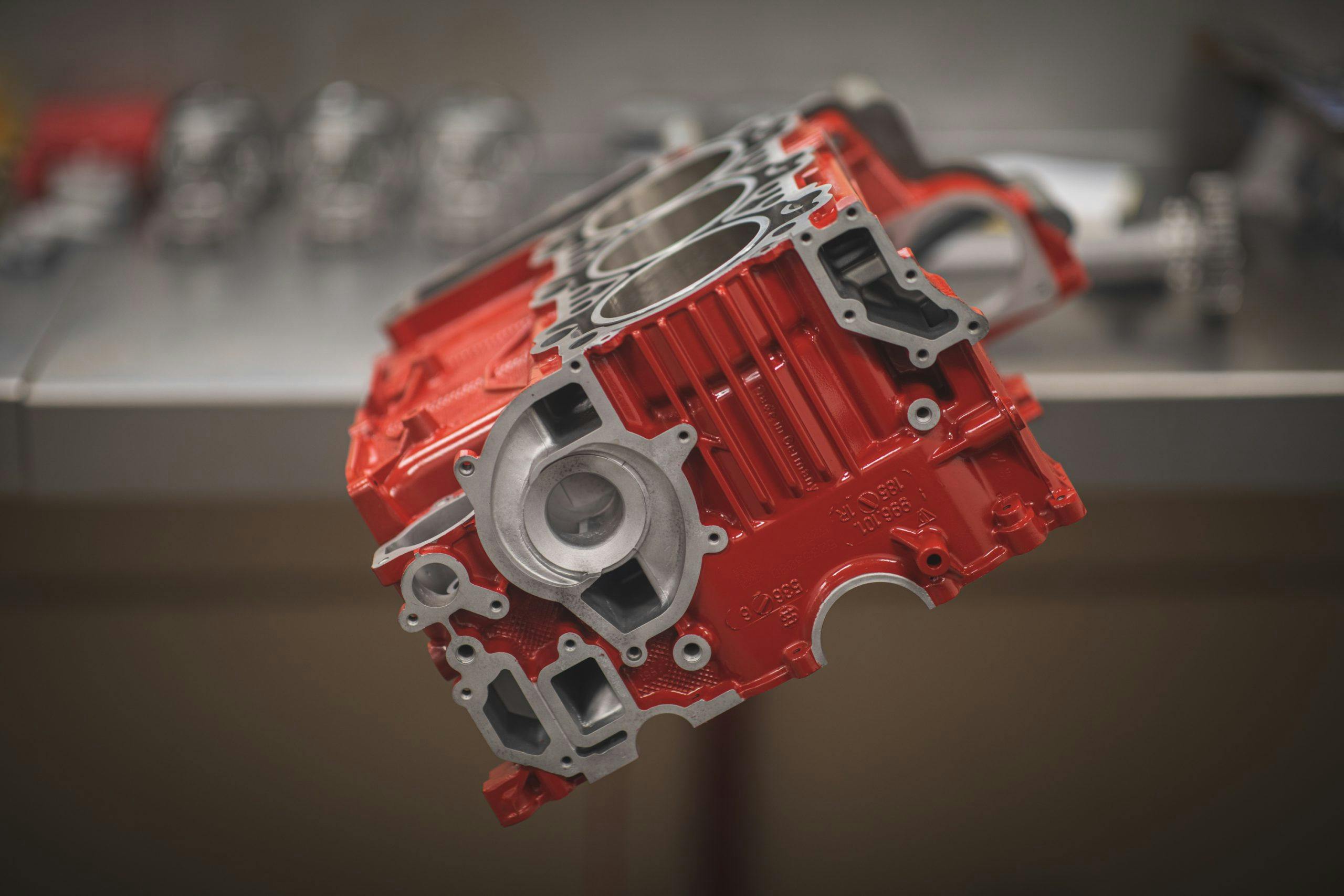

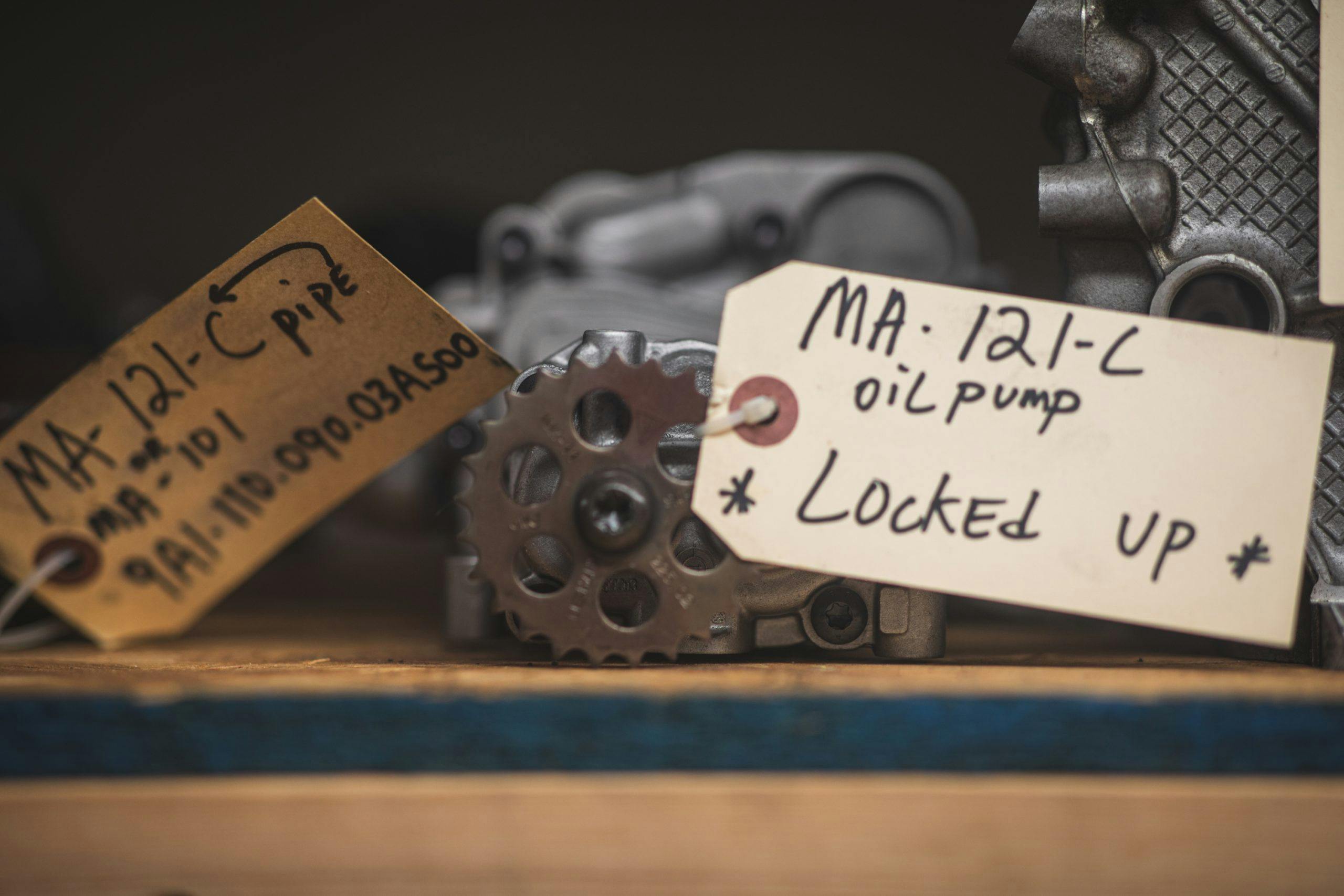

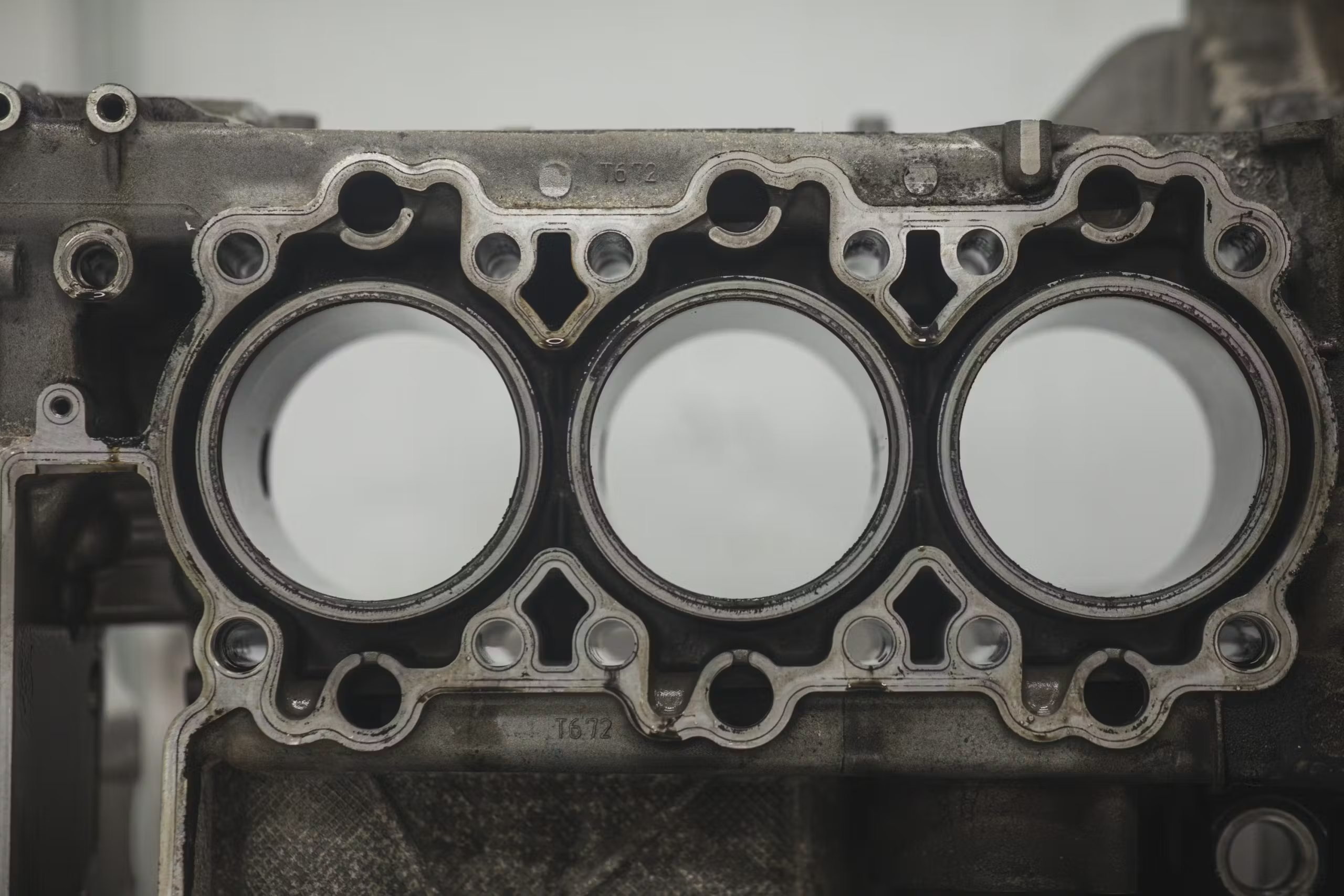

What he does is bring obsessive re-engineering and top-shelf components to a family of engines that are about as well regarded in the Porsche community as an oil-soaked sock. If you skip the stout and reliability-focused “Stocker” build, both the “Stage I” and “Stage II” bores out the cylinders to increase displacement by 0.2-liters and slots in Nikasil cylinder liners. The “Stage II” is by far the most popular build, carrying everything offered in the “Stage I,” only now with a gut full of billet connecting rods and forged pistons. The heads are ported and polished, with customers given the opportunity to dish out for optional top-level extras like lightweight valves and spring upgrades. Regardless of package, each FSI build packs Raby’s patented IMS fix, replacing Porsche’s failure-prone sealed ball bearings with a pressure-fed oil-lubricated plain bearing.

The invoice for these services is not for the faint of wallet. The Stage II will set you back $30,000. If you’ve really got it bad, $70,000 will net you FSI’s “R-Series” engine—a high-compression reactor that makes up to 460 hp at the crank—(with a range of displacements from 3.8 to 4.4 liters)—that sounds like a chainsaw fitted with starship Enterprise’s warp drive. Of course, the “R-Series” engines are far from settled science; Raby is pushing for a 500 crank-hp “R-Series” by the end of 2023.

Don’t bother breaking out the whiteboard for some visual ideation—nothing about these upgrades makes any financial sense whatsoever. Although Raby notes that some customers have been able to “cash out” profitably thanks to the rise in 996 values and the longstanding reputation of his builds, the napkin math in 2022 says you’ll need to outlay something like $60,000 for a clean 996 Carrera with the Stage II engine, and that’s before you start futzing around with the brakes, wheels, and suspension. What, you were going to just stop with what’s under the decklid?

Raby, ever the straight shooter, doesn’t try to justify the outlay with some revisionist history of Porsche’s water-cooled engines. “In some ways, I love it [the M96],” he says. “But, I really hate the practice behind it—I hate that Porsche basically sold out all the engineers and prior people who had done so much to build engines that are worth a damn, and to set itself up for just-in-time manufacturing.”

FSI’s workflow is decidedly not “just-in-time.” Customer builds of all scales—each handled through an intricate filing and progress-check scheduling system involving manilla folders in the office’s “War Room”—carry the full weight of thousands of developmental hours. “To me, none of this is about the engine. It’s about process of doing this,” he says back in the office. “The engine is just a culmination; It took me working on an engine in a hog pen with dirt floor to get to this point. You’re not buying just this engine, you’re buying a few thousand engines from me that we’ve learned from.”

Despite his outstanding success in the Porsche space, Raby’s more interested in air-cooled stuff with a few less cylinders and a few less computers to worry about. A lifelong devoted Volkswagen enthusiast, he notes that the newest car he owns, aside from his tow-rig, is an air-cooled 993. His watercooled “M9X” program started as a secret side business to his main passion—building micron-precise VW Type 4 flat-four engines. Raby’s Aircooled Technology (RAT) was the first division under Raby Enterprises and remains his primary focus today; from what we gathered, outside of the rarified R-Series builds, he leaves most of the day-to-day prep of customer engines to his well-oiled staff in Cleveland, Georgia, squirreling himself away in his large RAT workshop located on his private, personal property a short drive away.

Yet Raby understands the fervor of his customers, who he says aren’t traditional Porschephiles. “These are a new breed. They wanted this car forever; some of these guys had this car on the poster on their wall,” Raby noted as we walked through his workshop. As he showed us his engine dyno room—the only engine-out, Porsche-focused dyno outside of Germany by his reckoning—he added, “We’re dealing with pure emotions here, stuff that’s not quantifiable. I don’t do work on someone’s car unless they are absolutely sure they absolutely love this car, and they do.”

Two cars were pulled from FSI’s customer fleet for our sampling. First, a 997 Carrera 4 Cabriolet with a Stage II FSI engine, making 325 hp at the wheels and around 400 at the flywheel. This drop-top was a fascinating window into what type of enthusiast gravitates toward FSI. From the outside, nothing about this dark silver C4 denoted there was almost $40,000 buzzing under that rear decklid, nor did the well-lived interior. So, think of it as the antithesis of a 1980s Gemballa Porsche. Even as we calmly cruised through intersections and past prowling cops on our way to backroads, the physical and aural experience was subtler than the numbers and dollar signs might have you believe.

Blurred trees and echoing foothills immediately organized our thoughts. The duality is incredible; what initially felt like no more than a standard 997 with a sport exhaust evolved into a wonderful cacophony of rip and rasp akin to an angle grinder cutting into a pipe organ. These engines, when stock, need lots of revs—peak torque came around 4500 rpm. Not this one—a deep well of torque gave way to seemingly endless acceleration.

A 1999 996.1 Carrera with a Stage I package idled grumpily in FSI’s courtyard upon our return. This 3.6-liter’s 360 crank hp is a significant boost from the stock 3.4-liter’s original 296 hp, and puts it dead-nuts-even with a contemporary 996.1 911 GT3. And, as with the other car, it feels shockingly refined. Everything is completely turnkey and wonderfully confidence inspiring; even at parking lot speeds, there’s not a single whiff of “project car” growing pains to be found.

As with the 997’s Stage II, power is remarkably progressive and the torque butter-thick. The Stage I was predictably less explosive, but redline arrived in a rush, offering up somewhat muted flat-six clatter and zing but a wonderfully strong sense of acceleration that feels broader than the contemporary 996 GT3. With a proper engine, this early build 996 came to life; its excellent steering feel and a shockingly decontented interior lent a rather vintage vibe to the whole experience.

That purity may be what customers are really paying for here, and we don’t blame them.

These days, hot-rodding a 356 or air-cooled 911 is fraught with preconceived notions of what is tasteful and what the market will accept. There are rules. In contrast, no one is stopping you from making a 996 your own. You can do whatever you want to that 1999 Carrera, and no purist would bat an eye. Cage it, strip it out, hunker it down—who cares? It’s a 996, and if you love it—if you really, really love it—then use this transitory affordability to create the Porsche of your dreams. We’re sure Jake Raby and Flat Six Innovations would love to help out.

Good evening I have a 1998 built 996

I have some pictures. Let me know your opinion engine was re built at 100,000

Now has 125000 send me your email to sent you some pictures