At Ferrari, racing great Phil Hill was the odd man out

A couple of lifetimes ago, I phoned up Phil Hill to interview him about his kid Derek, then attempting to climb racing’s greasy pole with a seat in the Barber Dodge Pro Series. We had a pleasant conversation, and I got some good quotes. A little while later, the phone rang; it was Hill calling to amend some things. A few minutes later, he called back to amend some of the amendments.

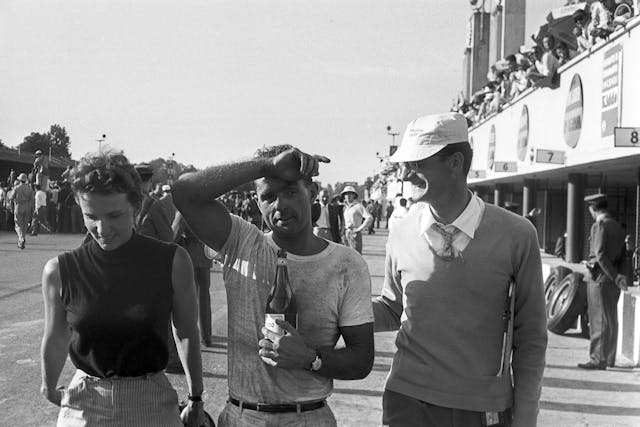

America’s only native-born F1 champion was apparently like that, a perfectionist obsessed with details, a trait that served him well later in life as a frequent Pebble Beach Concours entrant and partner in the Hill & Vaughn restoration shop. It was said that back when he raced, Hill, who died in 2008, always walked or slow-drove a circuit in advance, stooping to remove leaves and noting where overhanging branches might drip dew on a corner. That he would nervously start cleaning his goggles hours ahead of a race and still be cleaning them two minutes before the start.

“He was so taut,” observed one of his rivals, Stirling Moss, “so overwrought much of the time that one would have thought that he’d have been exhausted from sheer tension inside of 200 miles.”

Hill thus seemed an unlikely addition to Scuderia Ferrari’s roster, which he joined full time in 1956 as “the ninth man on a nine-man team,” noted Sports Illustrated. Ever since the great Tazio Nuvolari’s epic drives for the fledgling Scuderia in the 1930s, Enzo had searched for a new garibaldino, a soldier in the mold of the Italian hero Garibaldi, with the same flair, fearlessness, and singular devotion to victory.

Hill didn’t fit the profile. Besides being manifestly cautious—he said an ulcer diagnosed in 1953 came from the epiphany that racing was deadly—Hill had other interests such as classical music and art, which Enzo considered distractions for dilettantes. And Hill, a bachelor, seemed to live a monk’s existence, spurning advances from female admirers. In a squad of habitually libidinous Italians, that left him the odd man out. They dubbed him “Hamlet in a helmet.”

Hill had reason to be wary. He was an eyewitness from the pit wall to Pierre Levegh’s 1955 Le Mans crash, ducking just in time to miss debris thrown from the flaming Mercedes as it exploded into the crowd. And Hill joined Enzo’s Scuderia as death gripped its ranks. First Alberto Ascari in 1955, then Eugenio Castellotti, Alfonso de Portago, and Luigi Musso. In 1958, after becoming the first Yank to crew a winning car at Le Mans, Hill was moved up to the A-team, slated to drive F1 for the ’59 season. But only because teammate Peter Collins had died that August at the Nürburgring.

Hill’s promotion coincided with a shining moment for the Scuderia. For 1961, it had finally embraced the future with Vittorio Jano’s mid-engine Tipo 156, the famous “sharknose.” The car’s 1.5-liter, 120-degree “Dino” V-6 was the class of the field. Though Hill won only two races, he and teammate Wolfgang von Trips dueled for the championship up to the final European round at Monza. On the second lap, von Trips tangled with Jim Clark’s Lotus, and von Trips launched into the crowd, killing himself and 15 bystanders. Hill clinched the championship but under dreadful circumstances; he described von Trips’s funeral as one of the worst days of his life.

According to Hill, Enzo never said a word of thanks. Like many drivers, Hill saw Enzo as a father figure with a lot of similarities to his own father, and Enzo knew it and used it, stirring up sibling rivalry in the team to extract maximum effort. However, the Old Man unilaterally decided that Hill had lost interest in racing and fired him at the end of the ’62 season, seeing in the young bike racer John Surtees his next garibaldino. “I can’t say I’m heartbroken,” was Hill’s response.

“They were an absurd mob,” he told Ferrari biographer Brock Yates years later. “Ferrari was surrounded by flunkies, all seeking some sort of favor or approval.” Hill had been one of them. He quit racing for good in 1967, relieved to be one of few survivors from his era.

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Phil was not the odd man out. He was a man before his time.

Back in the day drivers were piss and vinegar and were willing to risk dying at any race to reap the win and rewards. They lived for the day as the next may never come.

Phil was more grounded and self preserving. He wanted to win and loved to drive but he had that self preservation about him that let him out live his rivals.

Enzo was driven and expected his drivers to give all including their life if necessary to get the most out of the machine. Yes his drivers were soldiers.

Phil took in all that was around him and looked to lower the risks and improve the performance. Today imagine him with the technology we have today that he could study and learn where to be faster?

Phil was a smart driver and had no death wish in an era that too many died. He Jackie and Dan Gurney brought a new thing to racing and that was preservation. They saw too many die around them and because of them few pay the price today.

Aaron and hyperv6 offer some great insights on Phil Hill. Phil stood out “from the crowd” in some ways for sure. Yet, what is most important to me is the last paragraph of hyperv6’s comment, “he, Jackie and Dan Gurney brought a new thing to racing and that was preservation”. The growth of racing safety was key for the sports survival. ;We are all thankful for their contributions.

Phil Hill is an interesting driver and the odd man for Ferrari. Enzo didn’t have patience for anything it seems and expected his drivers to blindly obey. I do agree with others if he had been racing in a later time with the safety and knowledge that can be gained in car these days what might he have further become.

I was lucky enough to spend some time with Mr. Hill in 1992 at a local historic race.

One of the nicest people in racing and the automotive world.

I now own a few of his wrist watches (Gooding & co. auction) that I wear proudly.

Phil understood the machinery. Because of this, to a degree, it put him in a different perspective from Enzo. Enzo apparently was intent that his drivers go as fast as they could and it was relatively OK if the car broke while leading. Phil, because of his affinity for the car, would back off as might become necessary to finish a race rather than destroy the car.

As for Phil’s classic car passion, pre-Hill & Vaughn, he restored his Brunn bodied 1938 Packard 12. Later as Hill & Vaugh, they were know as the best Packard shop in the western US. He made sure that the restorations not only looked good but were properly functional.

I was lucky enough to have fallen in with the local classic car scene in LA at a young age. I met Phil Hill early on, in my teens, and would run into him at many different venues, from the local Concourse, to the first of the auctions in the early ’70s. Eventually, I was showing my own cars and driving in the same events that he attended.

I remember when he showed up in his freshly restored brass era Packard at “Diagnosis and Service”, a local Ferrari garage/dealer across the street from my office. I walked over, and found Phil standing next to the car. He recognized me, remembered my name, and began to show me various features of the incredibly turned out Packard. Noting the matte finish on the side lights (as opposed to the polished brass on the headlights), he said that this was original, then pulled out a book on Packard coachwork, showing his car, when it was “in period”, explaining all this to me as though I was a Judge on the lawn at Pebble. This was gratifying, as well as educational. In a year, I would be showing a P III Rolls Royce at Pebble, and would have to defend decisions made in restoring the V12 Royce. It won class that year. I believe that Phil’s Packard also won.

Later, when I moved my office to Marina Del Rey, Hill and Vaughn opened up across the street. I used to drop by from time to time, to discuss my slow progressing E Type restoration, and visit friends. My Dad used to drop by to photograph the cars, including that recent award winning DuBonnet Hispano Suiza, which was parked outside one afternoon, back in the 80s…

Phil Hill managed to go through his racing career without hurting himself, or others, during a time that drivers usually didn’t live long enough to retire, let alone win a F1 Championship, or LeMans). An amazing fete, considering the cars, and the tracks of that era.

Phil Hill was local, and accessible. Easy to strike up a conversation, and often offering up some interesting commentary about his son’s racing (“Racing has become too safe”, he said at dinner one evening. “The drivers don’t have any fear of getting hurt” in assessing some of the risky behavior he was seeing on the track. An interesting observation by a driver during racing’s most dangerous period.