Alex Tremulis Designed the Tucker, but That’s Just the Tip of His Mad-Genius Iceberg

This year marks 100 years since Alex Tremulis was born. In celebration of his landmark contributions to the automotive world we love so much, we are resurfacing this article, originally published in April of 2019. Enjoy! — Ed.

Had Alex Tremulis merely designed the Tucker automobile, he would have earned a deserved place in automotive history. However, a presentation about his career, given last week at the Society of Automotive Engineers 2019 World Congress by his nephew Steve Tremulis, made it clear that he was not just an automotive one-hit wonder, that his influence extended beyond the world of automobiles, and even beyond terra firma altogether.

Born in Chicago in 1914 to Greek immigrant parents, Alexander Sarantos Tremulis’ passion for cars began at an early age. He got the car bug from his father, a physician who loved speed and used the excuse of having to make emergency house calls to buy a series of high-performance cars, including a Stutz, a Mercer, and a Duesenberg-powered Templar that Alex particularly liked.

Surprisingly, for someone who would make his living from his art, Tremulis failed art class in high school, perhaps because he was too busy playing hooky so he could go draw cars in the Stutz and Duesenberg factory showrooms. His drawings caught the eye of the Duesenberg sales manager and before he turned 20, in 1933, Alex was hired to design custom bodies under Duesenberg’s Walker nameplate. Three Duesenberg Model Js were bodied with his LaGrande Convertible Coupe design, highly regarded for its beautiful proportions.

Moving from the Chicago sales office to Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg’s Auburn, Indiana headquarters, he apprenticed under Gordon Buehrig, famous for his Cord 810. When Buehrig left the company in 1936, Tremulis was named chief stylist at the age of just 22, and in a rare case of improving on perfection, the flexible external side exhaust pipes he added to the supercharged 1937 Cord 812 were so popular that many were retrofitted to non-supercharged Cords.

As beautiful as the Cords were, the Great Depression took a toll on luxury car companies and ACD failed in 1937. Tremulis moved to Detroit where he worked briefly for General Motors under Harley Earl and then for Briggs, which made bodies for Chrysler, Ford, Packard, and other automakers.

In 1939, the peripatetic Tremulis was coaxed to come out to California by dancer Eleanor Powell, to help her PR agent, Sid Luft, start a custom car company. They built six custom Cadillacs before Luft totaled an uninsured car, putting an end to that venture. Before Custom Motors folded, though, his work was noticed by the president of American Bantam, for which Tremulis rendered the Hollywood and Riviera convertibles.

Alex returned to Briggs just in time to have a hand in Packard Clipper, working with Dutch Darrin, and then he produced what he later called a masterpiece of salesmanship, “The Measured Mile Creates a New Motor Car.” It was a written presentation he gave to Chrysler head K. T. Keller, augmented by sketches he had drawn of land speed record cars. Chrysler had been badly burned by the public’s rejection of the revolutionary, but odd-looking Airflow cars of the mid-1930s. Tremulis urged Keller to build on Chrysler’s technical skills with aerodynamics but with attractive streamlined designs.

Tremulis didn’t just sell Chrysler’s executives on streamlining their cars. He sold them on what he called “idea cars,” what we today call concept vehicles. As a result, Briggs constructed Tremulis’ own Chrysler Thunderbolt retractable hardtop and Ralph Roberts’ Chrysler Newport parade car, to much public acclaim. Those cars would go on to influence postwar car design across the industry.

When World War II broke out, he enlisted in the Air Force, hoping to draw airplanes. It took a while to get the military brass to put his talents to best use, but he eventually ended up at Wright Field on the advanced design team. For the first time in his career he had access to wind tunnels, increasing his technical knowledge about aerodynamics.

By 1944, the Allies had examples of the German V2 rockets fired at England that failed to detonate. American aircraft designers were inspired by the rockets and their gyroscopic stabilizers. They were also aware of the ME 262 jet fighter the Germans were starting to put into operation.

Tremulis came up with the idea of a jet-powered fighter-interceptor that would be launched to high altitude and then jettisoned by a rocket booster. That concept eventually became Boeing’s Dyna-Soar project, which gave birth to NASA’s Space Shuttle program. Today, Alex Tremulis is considered the godfather of the Space Shuttle.

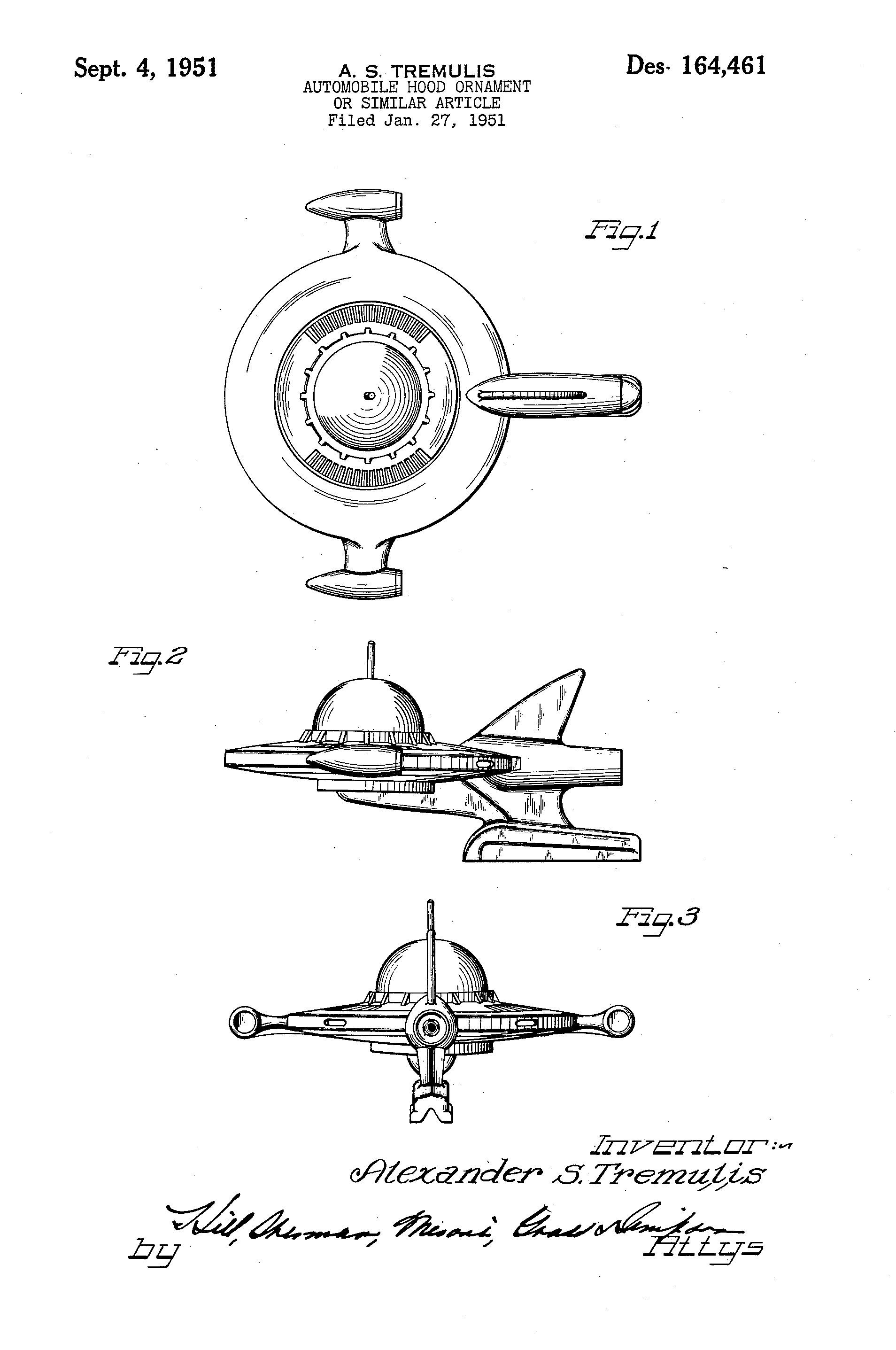

That wasn’t Tremulis’ only space-related influence. After news reports in 1947 spoke of a strange aircraft crashing near Roswell, New Mexico, Tremulis published his own speculations about flying saucers in Airline Pilot magazine, complete with his own drawing of a flying saucer approaching the earth from space. In the early 1950s, he even patented the design of a flying saucer hood ornament with a dome that lit up.

When peace returned, Alex moved back to his hometown of Chicago, where he worked for the Tammen and Denison industrial design firm, which produced some drawings for Preston Tucker’s automotive startup.

Tucker must have liked his work because in 1946 he hired Tremulis to be chief stylist for the 1948 Tucker.

Taking George Lawson’s original renderings for the Tucker Torpedo, which Preston Tucker had used to drum up publicity for his company, Tremulis turned them into a practical, producible design, adding his own idea for a center headlight that turned with the steering.

Despite his abilities, Tremulis also had a talent for getting hired by failing car companies. After Tucker folded amidst indictments for fraud, Alex moved on to Kaiser-Frazer and started an advanced design studio there.

When Kaiser-Frazer went under in 1952, Tremulis finally had some career stability when Ford’s head of styling, Elwood Engel, hired him. He stayed there for 12 years, including a stint running Ford Advanced Design, but he was considered insubordinate by his superiors—a bit of a corporate anarchist. Tremulis was ultimately demoted to working on pre-production Thunderbirds.

While at Ford, he came up with designs so advanced they are still considered way out there today. There was the atomic-powered Nucleon, the gyro-stabilized two-wheeled Gyron, and the six-wheeled Seattle-ite XXI, in honor of the Seattle World’s Fair.

The Seattle-ite had a modular front power unit that, at least conceptually, had a removable front power module with hydrogen fuel cell and atomic options.

One of his more conventional designs at Ford was the Thunderbird-based 1956 Mexico concept that looked more like a “Birdcage” Maserati than a ’56 T-Bird.

Eventually wearing out his welcome at Ford, in 1963 Tremulis set up his own design studio in Ann Arbor.

Tremulis had an abiding interest in the land speed record since he was a kid. While a spectator at the annual running on the Bonneville Salt Flats, Tremulis met Bob Leppan’s team from his Detroit Triumph dealership that was making a go at the motorcycle record with a twin-engine powered streamliner. There were stability issues with the bike at high speed and Tremulis offered to design them a new body. This would become known as the Gyronaut X1, after the gyros that he hoped would help stabilize the bike.

As it turned out, the Gyronaut used retractable outriggers, not gyros, to stay upright at slower speeds, but Tremulis’ aero design helped the Gyronaut reach a two-wheeled land speed record of 245.667 mph in 1966. The Gyronaut X1 later crashed trying to retake the record and was retired from record attempts. In recent years, Steve Tremulis has been part of an effort to restore the motorcycle that is nearing completion.

Tremulis did see his concept of a gyro-stabilized two-wheeled car come to fruition—sort of. Tom Summers had worked on gyroscopes since World War II. In 1966 he started the Gyrocar Company and raised $750,000 to bring Tremulis onboard the project and build a single prototype Gyro-X, a tandem two-seater with retractable outrigger wheels, powered by an 80-horsepower engine. Once again, though, Tremulis found himself associated with a failing venture and in 1970, Gyrocar went bankrupt. The Gyro-X survives in the collection of the Lane Motor Museum. The automotive oddity museum spent half a million dollars restoring it to operational status, including having a custom $250,000 gyroscope fabricated.

In 1968, Tremulis moved out to the West Coast, setting up his studio in Ventura, California, where he worked as a contractor for a variety of companies, including Subaru. Once again he struck out against convention with the Subaru Brat, a mini pickup truck made by cutting off the roof of a station wagon, with two rear-facing seats mounted in the bed to skirt past the 25-percent “chicken tax” tariff then in place on small imported trucks.

After a long and fruitful career, Alex Tremulis passed away in Ventura in 1991 at the age of 77. Nearly a decade before his death, in 1982, he was elected to the Automotive Hall of Fame. In 1987, the Society of Automotive Engineers honored him for his design of the Tucker, calling it one of the “significant automobiles of the past half century.” That is undoubtedly true, but only a part of this great man’s story.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Has anyone notices it used to be that every company had a big name designer or used a designer with a big name that left a trail of great car designs.

Today you hear few names and if you do they are one hit wonders or if they did more than one you seldom hear a name connected to it.

Yes aero has kill a lot of design and CUV model are hard to be creative with. But still there are some cars that you just never hear much out of.

I feel the wind tunnel has become too much the designer anymore. I wish we could get back to making designs you not just see but feel inside.

It’s almost obvious that the saucer hood ornament inspired the starship Enterprise.

While some of his designs were a bit outlandish, many DID point the way towards future developments.

Humourous Definition Department — The use of GYROSCOPES is a long-proven method of maintaining stability, particularly with water and air craft.

For the uninitiated, a gyroscope is a spinning disc of some kind that keeps its orientation despite angular changes of its base: tilt the boat and the gyroscope stays in its horizontal/vertical position.

Now the word gyro usually brings to mind the savory Greek edible.

Its effect on balance and stability would only come from the consumption of many, making it ballast.