After a near-fatal, 200+ mph wreck, this Enzo’s owner rebuilt. That was 65,000 miles ago.

If you happen to be cruising the roads between Provo, Utah, and the state’s southern border, you have a decent chance of spotting Richard Losee’s Enzo, flaming red and roaring, with curves that would make Italy’s Forcella Lavardet mountain pass blush with envy.

As of today, his Enzo’s odometer has rolled up more than 93,000 miles on its journeys, which are most often logged during 550-mile round trips that have been deliberately plotted, even if the end goal is sometimes simply to grab root beer floats with a troubled kid.

Most people would never take such an immaculate machine out on the open road, wouldn’t risk a pothole or a glancing dent from the errant door swing of a Toyota Corolla. Richard Losee is not most people. For one thing, most people don’t own one Ferrari, let alone upward of 10, let alone one of only 400 Ferrari Enzos that rolled off the assembly line in the early 2000s—which put him in league with the Pope, at least for a time. For another, Losee actually drives his Ferraris. Upon taking delivery of the Enzo in 2003, he almost immediately set off on a 1500-mile test drive with Road & Track, writing about his journey and continuing to add thousands of miles each year against most people’s better judgment.

“It’s just a car,” Losee says, confidently leaning back in his chair. He learned his love of cars from his father, a jeweler who—in addition to his Ferraris, Rolls-Royces, and other collectible automobiles—owned the actual 1963 Aston Martin DB5 Sean Connery drove as James Bond in Goldfinger, gadgets and all. With an immaculate head of hair, Losee is still handsome at 65 and doesn’t seem precious about much. “We went to Ferrari and I said, ‘I’m going to keep the Enzo. I’m going to drive it. And I’m going to put a bunch of miles on it.’”

Losee is a man of contradictions, wealthy and happy to enthusiastically pontificate about his hangar full of supercars, a helicopter, a vintage Riva wooden speedboat, and seemingly any toy one could imagine. He’s also generous, able to use his money to make better days for hundreds of others throughout his life. He’s enjoyed the fortune afforded him by his family’s jewelry and cosmetology businesses, and he has also had stints as an award-winning film actor, writer, and director. But he’s prouder for having founded Cirque Lodge, an addiction treatment center in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains, alongside Boni, his wife of 46 years.

Of course, he’s quick to detail Boni’s credentials as a beauty queen, too.

Losee spreads his arms as he speaks, loudly punctuating the most important elements of his story. But he’s humble in its telling, so long as you tell it right. Because what Losee’s best known for is crashing his Enzo, spreading its parts “like a downed jet” across a quarter-mile of Utah desert and flipping it a half-dozen times. His memory of the event is foggy—for good reason—but what he does know is the August 2006 Wall Street Journal cover piece that followed got his story wrong.

“It just reads like some guy who could afford to buy the car but didn’t know how to drive it,” Losee argues, still somewhat frustrated more than 15 years on. “I mean, that’s a story. That sells stuff. That’s not exactly what they wrote, but that’s what I chose to read.”

To set the record straight: Losee can drive. Among his accolades, he’s won multiple Ferrari Challenge rallies and also claimed the 1997 SCCA Group 2 national Pro Rally championship, having steered a Volkswagen Golf GTI Mk II across the finish alongside co-pilot Kent Livingston.

The Enzo crash is more the fault of Losee’s hubris peaking during the 2006 Fast Pass Road Rally. More than merely a parade of luxury cars, Fast Pass was a charity event during which notable drivers cruised to small towns throughout Utah, stopping for lunches and raising money for whatever each town needed, including funding for parks and schools. The event culminated with drivers racing solo heats down a closed, 14-mile stretch of Utah’s State Route 257, speeding as fast as they could and donating whatever theoretical fines they tallied to the state’s Fallen Officers Fund—which supports the families of Utah Highway Patrol Troopers killed and injured in the line of duty.

“I knew I was going to go fast,” says Losee, who by that point had put more than 30,000 miles on the Enzo, true to his word with Ferrari. “I knew I wanted to get a really big ticket for the charity. Plus it was for bragging rights.”

Losee had arranged to meet with a state trooper to pre-drive the relatively straight two-lane path of blacktop, flanked by distant mountains. Instead, he trusted the highway patrolman who had told him the course had been driven at 100 mph by three fellow troopers without issue.

“They had warned us of some whoops early on in the run. I didn’t pay any attention to it because I had 1400 pounds of downforce with the Enzo,” Losee says. “I was one of the first cars to run, and all I remember is the start line—I had a full-face helmet on. I remember them waving me off. I remember looking down at the speedometer thinking I needed to keep my speed up. The next thing I remember, I was in a very large slide and thinking to myself, ‘This is not good.’”

Losee hit one of those whoops going an estimated 206 mph. For a few seconds, he was airborne. Then the Enzo’s undercarriage smashed to the pavement, sliding right to left across the road into a berm that acted like a ramp, sending the Enzo flying 219 feet, according to crash investigators, before rolling across the desert once it touched down. Losee and his Enzo somehow eventually ended upright on the side of the road—the driver relatively intact despite the car being completely mangled.

The first person to the scene thought Losee had been decapitated, as the “scalped” crown of the helmet had rolled completely forward over his face, the neck strap tightly cutting off his air supply. He wasn’t breathing, he had no pulse, and he had fractured the C1 and C2 vertebrae, right below his skull. After careful effort, Losee was freed from the wreck and quickly airlifted to a Provo hospital, where he was met by Boni and his three kids when he came to. He confidently asked for a camera, and that afternoon, he sent a message to other drivers at the event saying he’d be the first to sign up again next year, but he admits to having no recollection of it.

“I was in a halo or whatever they call them for about six months. They wouldn’t let me drive for six months,” Losee laments, as if that was the worst of it. “My wife had to drive me everywhere. I was under a neurosurgeon’s care for a year, but they got me breathing.”

Two giant crates, each large enough to hold the ark of the covenant, now house the Enzo parts picked off the highway following Losee’s crash. The only pieces remotely intact were the chassis and the engine, which was largely rebuilt but still bears battle scars of its tumble through the desert. Losee jokes that people would ask permission to “sneak a peek” at the piled-up mess of Enzo detritus that filled two garage stalls at nearby Miller Motorsports Park before the pieces were boxed and transported to his hangar. But Losee was slow to view the carnage, having other plans for the car.

“I wanted it to live,” Losee says. “I could have bought another Enzo. I didn’t want another Enzo. I wanted this Enzo. It was my car. So 18 months after the crash, I went to Boni and said, ‘I want to rebuild it. And I want to take it on the salt flats.’ Boni knows me well, and she just quietly said OK.”

Here, another bit of hubris. No one would fault Losee for leaving the Enzo forever in his rearview or turning the mangled mess into a work of art he could hang on the wall or cover with glass to craft into a coffee table. Instead, he not only wanted to rebuild it—itself a seemingly absurd task—but he aimed to break a world record at Bonneville once he did.

Losee’s team—led by Randy Felice, an authorized Ferrari tech at Steve Harris Imports in Salt Lake City with more than 25 years of experience—took 30 months to reconstruct the car, with assistance and sponsorships from Ferrari of North America and Miller Motorsports.

The original chassis, engine, cluster, and seats were salvaged from the wreck. The carbon-fiber tub that had been “ripped to shards” was also painstakingly rebuilt and checked for its integrity via ultrasound by an expert who often works with fighter jet aircraft. An identical Enzo body, in the same Ferrari red, “no paint needed,” was found stored in crates at Pininfarina HQ in Cambiano, Italy. “So I cut a deal with the owner,” Losee explains. Controversially, twin turbos were added to the Enzo for increased power, eventually producing 847 horsepower, and a roll bar was added for safety.

“I consider myself a purist,” Losee says. “If I hadn’t destroyed it, I’d have never put twin turbos on it. I would have never put a roll bar in it. The only reason I did that is because I could. No one was going to care that I resurrected a car that had been destroyed. If I’d fixed it and tried to make it all perfect again, it was still going to be the wrecked Enzo. So we made it stronger and we made it faster. Nobody expected the car to fire right up,” he says, remembering the first time they turned over the engine since the crash. “Nobody expected the car to start, and it goes to 8000 rpm, just like that. It wanted to live!”

Losee pleads ignorance on the ultimate cost of the Enzo’s rebuild, mostly because he didn’t bother counting. “There was no budget, just a desire to complete the rebuild correctly … but it was a lot.” However, after all the money and all the time and all the effort it took to get the Enzo back to the starting line, Losee, again contradicting his self-assured ego with humility, today admits he didn’t want to drive it. Losee is proud to say that the car saved his life by doing exactly what it was supposed to do: shedding various and sundry parts to keep the occupant alive in the cockpit. However, he wasn’t eager to hop in when he took the rebuilt Enzo out onto the salt flats in 2010 for its first ride.

“This is something I haven’t shared with many people: I was afraid,” Losee says, choking up. “I didn’t have any idea I would feel that way until I got in the car. I didn’t really think about it beforehand.” Losee quickly shakes himself out of it, spreading his arms again as he returns with his patented boom: “Driving on the salt is like driving on ice!”

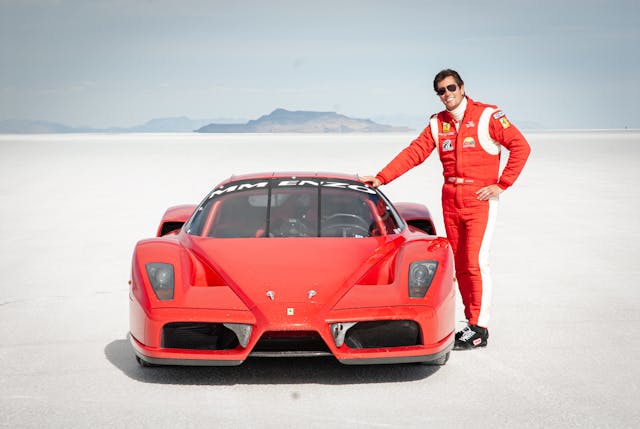

Chasing the 360-cubic-inch C Blown Fuel Modified Sport category speed record of 213 mph side by side against an ultralong-wheelbase, front-wheel-drive, blown big-block Chevy based loosely on a Triumph—which Losee mostly only recalls as being “crazy fast”—the Enzo hit 221 mph on his first run. Losee’s competitor hit about 270 mph, leaving no doubt. But the rules are you have to get your car across the line twice and average the figures, so when the crazy fast car had engine problems on its second run and averaged 231 mph, Losee saw an opportunity.

“We had done all of this with stock gearing in the car,” Losee says. “So I asked, ‘Have we got a shot at this?’ The tech, Shane Tecklenburg, goes and does all these calculations, and he says, ‘If I raise the rpm limit on the stock engine, if I raise the boost from what we’ve been running—which really wasn’t that high—we got a shot at this.’ And I said, ‘Do it.’”

After a comedy of errors that included multiple misfirings of Losee’s rear chute—designed to slow the car once it crosses the line, it instead deployed mid-attempt—during otherwise great runs and, by his account, some “not very nice” words for his crew, Losee finally got in a clean 5-mile run. “The car is squirrely, but it’s so much fun and I’m not afraid of it anymore,” he remembers. “It’s blister-ing up the track, and on that first run, we did 237 mph and some change. That is the fastest documented Ferrari in history. Period. We’ve held the record for over 10 years.”

Losee’s second scorch of the day was even faster, pushing past 238 mph and giving him and his team a world class record with an average speed of 237.6 mph. “I was the last car to run on the last day,” he says. “We had a good run, the chute didn’t pre-deploy, and I hit the 5-mile marker, which was the end. Then I thought, ‘Now, was that the 5-mile marker or the 4-mile marker?’ So I ran an extra mile just to be sure. I will never forget that last mile.”

Losee’s team held the speed record for a year, “and then that guy with the crazy fast car came back and blew us out of the water!” he says, laughing. “But I didn’t care. I got back on the horse. I got back on the horse, and that was not about setting a speed record at Bonneville. That was nice, and if I hadn’t set a record, it wouldn’t have been nearly as cool. But it was about getting back on the horse. I knew I was going to be OK with myself again.”

Losee’s Enzo is now fast on its way to eclipsing 100,000 miles, which it should pass sometime in 2022. He’s proud to own it, to have had famed F1 driver Phil Hill take it for a spin, to have been featured extensively in Road & Track, to have raced it and rebuilt it and to have broken a few records along the way, but he thinks the work it’s doing now is its most important to date. Today, if you spot it carving through Utah, it’s likely being piloted by Clarence Habovstak—a passionate Ferrari owner himself, former board member of the Ferrari Owners Club, and former consulting producer for BBC’s Top Gear series—who has personally put 50,000 miles on the Enzo.

Habovstak is a close friend and sometime foil of Losee—the two are cut from different cloths, with the bearded Habovstak more often spotted in a cowboy hat and red sneakers. He’s quick to admit Losee is the handsome one. The two bicker constantly, with Habovstak being shushed before he gives away too many morsels of a good story Losee doesn’t want to be told. “Don’t share too much!” he cautions. Later, Losee claims that Habovstak tells stories just like his wife does: “They’re great stories, but they’re unashamedly embellished!”

Still, it’s obvious the two men have affection for one another—especially obvious given that Losee has tasked Habovstak with what he believes is the most important mission of the Enzo. Habovstak doesn’t drive it for fun—though he admits it’s a perk—or to add miles for an arbitrary goal. Instead, he’s often taking Make-A-Wish kids on dream road trips or sometimes filling the passenger seat with someone who’s willing to donate thousands to their charity, Cirque Lodge Foundation, for the privileged lift.

“It just represents so much more than what people may perceive as a pretentious object,” Habovstak says. “I had a young man who was struggling through high school and he had some serious health issues. He joined me for a ride, and we literally did a 500-mile road trip just to go get root beer floats and chat. It’s not just about putting miles on the car for the sake of tallying up the most miles we can on a Ferrari. We want each mile to mean something.” Habovstak is also pretty proud to have never gotten a ticket in a car that can do 237 mph, even if he can flip the license plate when needed, one of many defensive-only James Bond–esque gadgets added to the supercar in the years since Bonneville—along with a smokescreen, a homing device, an oil slick, a tack spreader, and a carbon-kevlar bulletproof spoiler.

“I think 100,000 miles is a good number, but to me, that’s just another step in its story,” Losee says. “The car is doing something more important today than any record it set at Bonneville. More than appearing on the cover of Road & Track. It’s doing some really cool work. There were people pretty upset that I’d wrecked this car. And I wasn’t very happy about it myself,” he says, which makes Habovstak nearly double over. “But it’s just a car. At the end of the day, it’s just a car. And if it was a Fiat 500, no one would care.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

what a great story.

Fantastic story!

The world needs more people like this man.

Totally agree! Given the resources I would love to do the same. This is both inspirational and aspirational!

Interesting story. Nice to see the car gets driven.

I have done one of the 500 runs in 2021. Clarence chatted the whole way telling me amazing stories of kids with problems turning their lives around coming from near total distraction to rebuilding their lives. If you are in in Utah and have a $1000 to spare you need to ride the Enzo with Clarence. Headsets for clear communication included.