Vision Thing: The art of the steal

Good artists copy, great artists steal” is a quote widely attributed to Pablo Picasso, most notably by Steve Jobs in 1996. It’s a delicious irony that although there is no concrete evidence that Picasso ever said it, the saying itself has altered over the years.

Author W.H. Davenport Adams wrote of Tennyson in The Gentlemen’s Magazine in 1892 that “great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.” The composer Igor Stravinsky said “a good composer does not imitate, he steals.” In 1974 author William Faulkner reportedly observed that “immature artists copy, great artists steal.”

Whatever the origin of the axiom, it’s not meant to be a trite comment on the nature of creativity.

Rather, the best creative works build upon what has gone before, repackage and reformulate it into something new and relevant.

Herman Melville was obsessed with Shakespeare, using the tragic characters of King Lear and Macbeth as inspiration for Ahab, as well as assimilating much of the bard’s construction of language when he wrote Moby Dick. That novel became the main inspiration for Nicholas Meyer when he wrote the script for 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, even going as far as placing a copy of the book in one shot to make the parallels explicit.

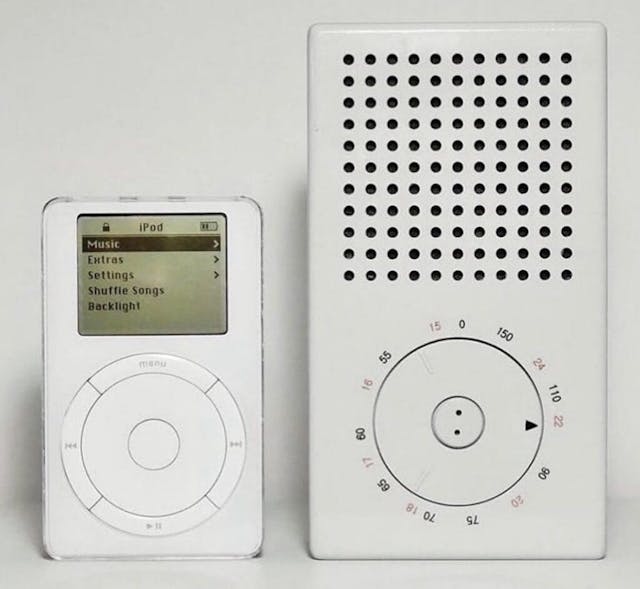

Armchair design critics love pointing out that much of Jony Ive’s work for Apple was rather more directly inspired by the work of Dieter Rams at Braun. However, even Steve Jobs admitted his company was not above reusing great ideas, and Rams literally wrote the book on modern industrial design, although the iPod scroll-wheel interface reputedly came from a Bang & Olufsen phone.

How do we learn? We learn by copying and understanding. How do we understand something? By pulling it apart, looking at the inner workings, and seeing how all the constituent pieces fit together. It makes no difference if it’s a concerto or a Camaro; only by looking at the how and the why can we carry those ideas forward and improve them.

When I was first starting out as a student of car design, one of our first lessons was to find a rendering we liked online and attempt to replicate it. By really studying someone else’s image and trying to work out how that artist represented highlights, shadows, and reflections, we could take our first steps in developing our own techniques and visual style.

Today, even as professionals in a studio, we use photos of existing vehicles or another render as an underlay. Why struggle getting the proportions correct for a muscle car, for example, when you can get your eye in using someone else’s work as a guide? I’m constantly telling my students that using an underlay is perfectly acceptable working practice, but it goes against their innocent ideas that everything they do should be completely original.

I recently had a student quietly reveal to me that they had two brilliant concepts they were keeping under their hat—no one had thought of these designs before. Imagine the look on their face when I gently explained I had seen similar ideas in the past and that it was very difficult to conceive of something truly original.

(Not to sound too egotistical, but one of the selfish reasons I love teaching is I do enjoy being the smartest person in the room.)

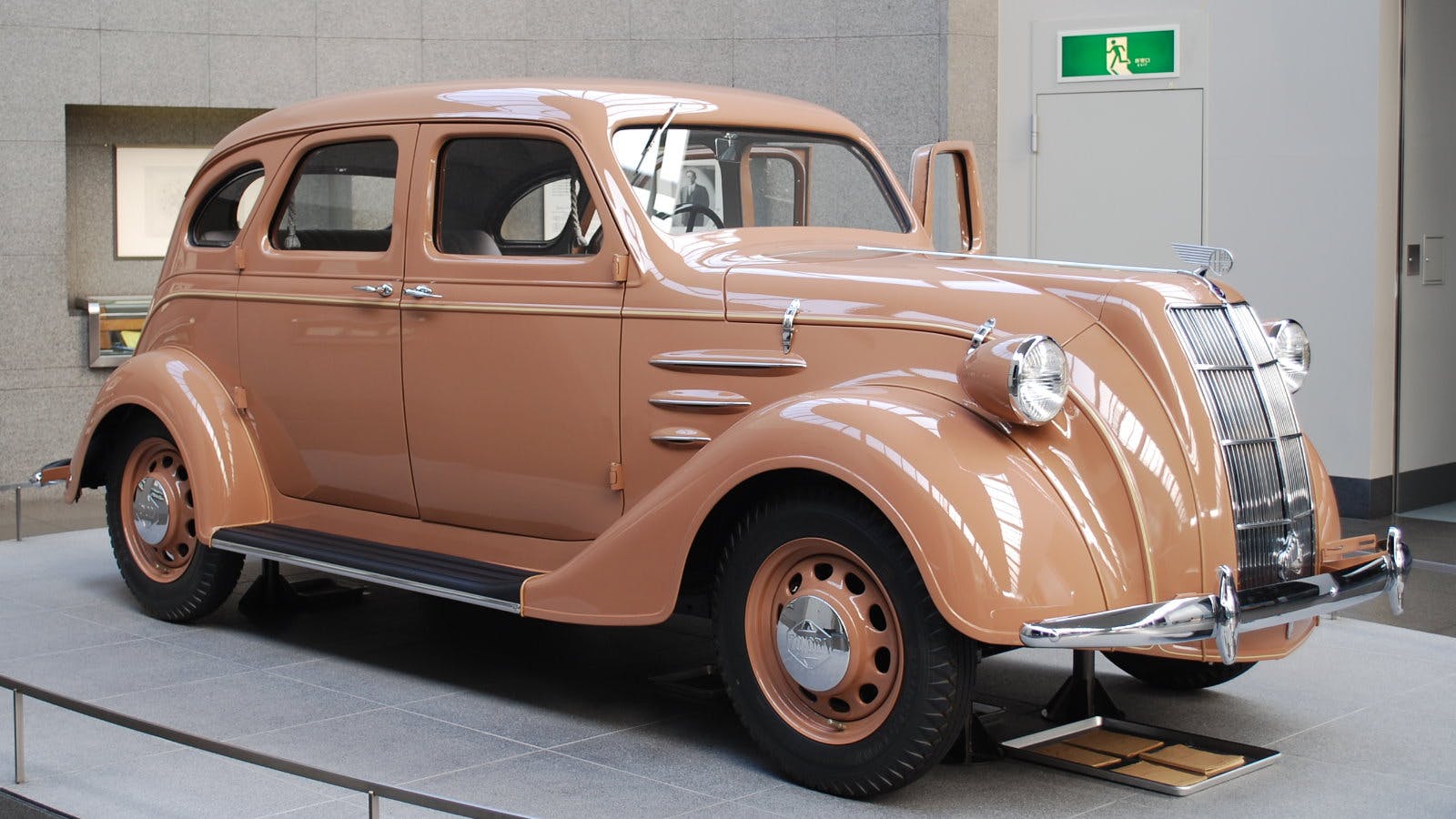

Nonetheless, we all have to start somewhere. When Kiichiro Toyoda decided to switch from producing looms to building cars in 1935, his first effort (the AA) was an almost carbon-copy of the DeSoto version of the Chrysler Airflow, presumably because the Airflow looked like the future at the time.

Because the Japanese economy wasn’t ready for passenger cars, Toyota switched its attention to trucks, basing its 1.5-ton G1 on similarly sized trucks from Ford and GM. After the war, Toyota chose to work with German engineers rather than with American or British companies, so its next attempt at a passenger car, the SA, was basically a front-engine, suicide-door version of the Beetle.

It’s unclear how much the first Nissan (née Datsun) was a copy of the diminutive Austin 7, but it was certainly extremely close.

When Honda decided to move from motorcycles to passenger cars in 1963, it took direct influence from small, cheap British roadsters of the day and built the S500. As the Japanese domestic car industry grew in stature and confidence, it began to copy American designs. The second-generation Toyota Crown from 1962 borrowed its look from the Ford Falcon. Later Crowns would lean heavily into the American aesthetic: bold grilles, strong use of chrome, and slightly squared-off volumes with a touch of the baroque.

Leveraging Japan’s talent for miniaturization, the first-generation Celicas were pocket-sized muscle-car clones. Shamelessly aping both the Camaro and the liftback Mustang, some versions even had three-bar vertical taillights. This wasn’t just a calculated attempt to appeal to the American market—Honda designers were learning from the day’s most influential car designs.

When the Japanese economy was heading towards its “bubble” period and its car manufacturers wanted to build world-beating sports cars, they turned their attention back towards Europe. The glass-backed RX7 in its first two generations took inspiration from the Porsche 924. When it came to the MX5, Mazda even had a Lotus Elan in the studio, so intent was it on nailing the character (if not the breakdowns) of the quintessential British roadster.

Japan is a country with a rich artistic and industrial design heritage; Sony was Apple before Apple existed. As such, it’s always surprised me that Japanese manufacturers have struggled to have any truly stand-out designs of their own, now that they’ve grown out of their copying-and-learning period. There are exceptions, of course—I’ve talked about how much I like and admire the Lexus LC 500—but think about your personal Japanese favorite or any of the JDM classics and more likely than not it’ll be a domestic version of something else.

When the Acura NSX came out I remember one particularly sniffy magazine review saying, “It’s not a Ferrari though, is it?” I don’t remember those same magazines criticizing the MX5 for not being an Elan. Even cars like the WRX or Mitsubishi Evo were venerated for their capabilities rather than their appearances.

The same pattern has been repeated with a more recent entrant into the global car business: China. But in an attempt to catch up, its designers are somewhat short-cutting the learning-and-understanding part of the process.

The Chinese are notorious for not simply taking inspiration from other products but for plagiarizing designs wholesale. The original Daewoo Matiz was derived from a rejected Italdesign concept for a new Fiat 500. Chery (no prizes for guessing where the name came from) liked it so much in 2003 they released the QQ, a blatant copy. GM, which by this time owned Daewoo Automotive, got hold of one and reportedly built a pair of drivable half-breed cars by combining parts from both a Matiz and a QQ.

Jaguar Land Rover eventually won a case in a Beijing court in 2019 over the Landwind X7, an ersatz Evoque clone. There’s been plenty of others; the Zotye SR7 was an Audi Q3 and the SR9 a Porsche Macan.

We shouldn’t let our amusement at these knock-offs obscure the facts of what’s really happening. China is attempting a crash course in how to design and build cars suitable for worldwide consumption.

When the South Koreans were starting out, Hyundai enlisted the help of Italian design firm Giugiaro to design its first domestic car, the Pony, in 1982. Rather amusingly, given the terrible state of the British car industry at the time, Hyundai then enlisted British help for the vehicle’s engineering. Hyundai’s second car, also designed by Giugiaro, was the Stellar, based on the European Ford Cortina.

Kia, in which Hyundai would come to own a majority stake after the 1997 Asian financial crisis, initially built Peugeots and Fiats under license, before rebadging Ford and Mazda models. Recognizing that design was crucial to their aspirations in Europe, in 2006 Kia hired Peter Schreyer to overhaul their rather neutral, nondescript range of vehicles inspired by their neighbors to the east. Taking the idea of “tiger economies” quite literally, he came up with the distinctive tiger-nose motif for the brand.

In stark contrast to the Japanese (and latterly Chinese), the Koreans haven’t really copied anyone; instead, they’ve hired in experienced design leadership, something I suspect would be anathema to Japanese pride.

I’ve read more than a few opinions recently that Kia and Hyundai are currently creating some of the best-designed cars available. I’m not so sure.

Certainly the Ioniq 5 and Ioniq 6 are getting people into a lather over their distinct appearances. The Ioniq 5 is a conventional but oversized hatchback volume covered in pixels and disjointed surfacing—it’s all novelty, and a little bit overdone for my taste. The Ioniq 6 is a streamliner with the same pixel pox and a tail that looks trodden on.

I’ve lamented previously about the pernicious effect of the ’80s aesthetic, but I’m slowly making my peace with the fact that like it or not, that’s where the popular taste is currently. Also, South Korea is a technologically advanced country, so it’s not entirely unexpected that electronics plays a big part in how its cars look.

What about the U.K., in so many ways a cultural magpie? Ford and GM designs, as we have discussed before, were heavily influenced throughout the ’60s and ’70s by the cross-Atlantic pollination of designers from Detroit. British Leyland, on the other hand, worked closely with Italians. Pininfarina had a hand in a number of Austins but wasn’t above plagiarizing itself—witness the similarities between the Austin Cambridge and Peugeot 404, something the studio repeated in the ’80s with the design of the Peugeot 405 and Alfa Romeo 164.

Another Italian, Giovanni Michelotti, worked extensively with Triumph, developing themes for sporting saloons he reused at BMW for the Neue Klasse cars. My favorite Aston Martin, the original V8 Vantage was designed by William Towns, who admitted borrowing heavily from the Mustang.

Each took something from somewhere else, and, in the best cases, made it their own. Britain learned from Europe and America, combining finesse and flash. America, emerging from the chrome-laden excess of the ’50s, looked to Europe to create some of the United States’ greatest-ever designs in the ’60s. Japan, recognizing its design leadership, remixed America’s greatest hits in the ’70s.

When Japan wanted to make sports cars in the ’80s, it looked to the place that did them best—Europe. Korea took a slightly more enlightened approach. Instead of taking the tried-and-tested classes, they hired a personal tutor, and it’s arguably paid dividends in their current design confidence.

It took roughly thirty years or so for these domestic industries to really come of age in the car-making business—to fully understand how the design of a car could reflect the tastes and desires of customers while offering them an emotional and usable product they really wanted, rather than needed, to own.

In America and Europe, this maturity point occurred around the time of the war, reflecting those countries’ head starts. Japan, starting just after the end of hostilities, got going by the ’70s. South Korea appears to be having its time in the sun now after starting in the ’80s, although part of me can’t help but feel we’re seeing something similar to the Japanese bubble, and there will be a retrenchment—especially if the EV revolution turns out to be anything but. The Chinese are attempting to take a short cut by copying everyone.

Time will tell if they will succeed or not, but one thing is certain: Companies that haven’t taken car design seriously in the past—like Dyson and its ill-fated car—have been doomed to fail.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Now there are some differences here.

Now in copying some are just a form of flattery. In the case where they try like the Toyota to copy parts of a Mustang. Mostly cases the copy is never better than the original.

In the case of the PT Cruzer and the HHR. Chrysler started with the ill fated Neon and made it into what they had. On the other hand Bob Lutz who did the PT at Chrysler was not at GM and had better under pinning’s and used the same designer to make a better PT.

Others like the NSX can be a better Ferrari but it is still not a Ferrari. Same with Harley Davidsons. You may have a better V twin but it is still not a Harley.

Then the Chinese just copy because they can get away with it. The Chevy and Cherry for example the Chevy fender will fit on a Cherry they stole the design so close.

To me much of the copying is more or less an excuse for poor creativity. Yes most of these have taken the easy way out. Unless they have built a better original it is just a weak scam in my view.

The issue with copying is that the average car buyer is distinctly visually conservative, they don’t want anything different, so the Asian manufacturers have been giving the Public exactly what they want, comfortingly familiar shapes, often grouped together into a single vehicle, and then softened and released of any original thought by focus groups…

If you want to see Japanese vehicle design at its best, you have to look at Motorcycles, where they have no real competition anymore (apart from the Cookie cutter Harley-a-likes of a couple of decades ago, which you could argue is now reversed as H-D try to find a language for more up-to-date bikes) so they have to come out with their best ideas on their own, look at something like the RC30 or the NR750, the Yamaha TZR reverse cylinder, or the Suzuki GSX-R range or RG500…

You could always count on mid-nineties Yamaha to do something bonkers – SZR660 or GTS1000 anyone? But yes you’re right in that the mainstream tend to follow each other with certain trends – like the current vogue for flying C and D pillars.

“…The Chinese are notorious for not simply taking inspiration from other products but for plagiarizing designs wholesale…”

Correct. This is why I don’t fear the Chinese military. Everything they have is just a cheap clone of the real thing. Have you seen their stealth fighter? Just a reskinned F22. Pathetic. Not an original idea in a country with, what? 2 Billion people???

There are historical and cultural reasons for this, which I’ve stayed away from talking about too specifically because it’s heading outside the remit of this column and slightly into geo-politics and history. But it all became very clear to me when I did a lot of research for a SAIC project I did while studying at the RCA. That, and my own observations of how Chinese students conduct themselves (it’s a lot deeper than just copying).

Scout to Bronco to Blazer

Ranchero to El Camino (Coupe Express is a jump earlier and not box connected to cab…)

Barracuda to Mustang to Camaro

Lark/Rambler to the big 3 all doing compact

VW air cooled rear engine line to Corvair line

Corvette to Thunderbird –ah finally GM does it first

GM generally wins at the steal though, almost always making the better selling version…

GMs problem is that is has good ideas (and a lot of bad ones!) but it never has the faith of it’s convictions. They can be very short sighted sometimes.

When the financial numbers don’t add up, the “faith of convictions” argument fails. Did Morris Garages ever build vehicles that outsold production? How about Triumph? Whenever any company has stockholders, in order to keep them happy that company has to make money. There have been countless efforts to make vehicles that are fun to drive and are attractively styled to some, but not to enough buyers to justify further production. You need to look no farther than Rolls-Royce and Bentley to understand how that works. VW and BMW are trying to keep the lights on, but for how much longer?

In China as long as you have friends in the government its OK with intellectual theft and blatant copying of “foreign” vehicles. Daewoo was not the only copied vehicle. The Toyota Hilux was blatantly copied by a Chinese manufacturer. The copying is a cheap way to build a lookalike at cheaper prices so you can undersell the non-chinese competitors all with blessings from the Chinese government with the hope once they steal enough intellectual properties or reverse engineer a competitiors part they will call it their own and sell it for less. The chinese are the worst but it does happen worldwide . Most manufacturers love to tear down competitors to see how they design and build stuff. You can learn from it. but the chinese will literally measure up everything and build an exact copy of the parts

Absolutely OEMs do tear apart competitor vehicles for costing and engineering analysis, and have been doing it for decades (see my previous column). Outside companies do it as well and sell that information, Sandy Munro being one (but he’s not the only company doing it). This ties into my point about pulling something apart, understanding it and trying to improve it and learn the lessons.

Which is not really what the Chinese are doing, which is more akin to counterfeiting (or was, they seem to have moved on a little from this now).

“…The Chinese are notorious for not simply taking inspiration from other products but for plagiarizing designs wholesale…” This is because in most of Asia copying is considered “flattery” not plagiarizing…they do not understand our thoughts on this as we don’t understand theirs; a simple cultural difference. They analyze a good product and make it better.

Except with China that’s blatantly not the case – a lot of their consumer products – not just cars, are very substandard because that’s one way to get the cost down.

This copy of the original Mini was unbeleivable, well sort of…….

https://carnewschina.com/2022/05/17/new-chinese-ev-company-clones-the-classic-mini/

Like a band will be influenced by other bands and may at times copy their style, maybe even licks, so to do designers. They problem is there does seem to be a creative desert we seem to have wandered into. So much me too design out there and copy and paste into bigger and smaller versions of the same box. Hopefully real style will make a comeback.

One of my earliest memories of ‘fox in the henhouse’ was 1962, when I was 11 years old. I have always been car-mad and would spend my August/September each year hanging around a local car-carrier yard to watch the new offerings being unloaded off the trucks. For brief moments the white car-covers would come off as the vehicles were taken off the carriers, then be quickly re-covered. Everything was so secretive. so, in ’62 the ’63 new cars were being unloaded. First thrill was the new Buick Riviera, with its gorgeous lines and advanced features. Wow! But wait! As the new Chrysler Company cars were being brought off the trucks, I noticed strange things: Plymouth Fury with vertical front signal lights like the Riviera, Dodge Coronet with taillights suspiciously similar to the Riviera, and big Chrysler with a rear c-pillar echoing the essence of the Riviera. I always wondered what corporate espionage went on building up to that year’s releases. Still remember it today, as clear as a bell. By the way, I grew up in Oshawa, Ontario, Canada, at one time a huge GM town.

For years I’ve noticed American pickup truck manufacturers copying Japanese truck styles (especially Chevrolet), but lately, I see the Japanese styles mimicking American styles.

Good article. Classically trained Steve Winwood once shrugged that there were 12 notes in Western music and only so many ways to arrange them. St. Vincent Millay, Marcel Duchamp, every great in every field bowed to a forebearer. Bill Mitchell cribbed from the ’36 Panhard Dynamic. Harley Earl, Dutch Darrin; all absorbed the work of others.

In 1958, Miles Davis told Nat Hentoff, “You know you can’t play anything on a horn Louis hasn’t played — I mean even modern.” Davis was referring to Armstrong’s work in the mid and late 1920s.