The bad wheel bearing that wasn’t

The real story starts about halfway through this piece. But if you’re a regular reader, you know that my stories are nothing without the proper context.

For a decade, I’ve written about “The Big Seven” things that are most likely to strand you on a road trip—fuel delivery issues, ignition issues, cooling system issues, charging system issues, belts, clutch hydraulics, and ball joints.

The first four items are fairly universal across makes and models, as well as on newer versus vintage cars. A dead fuel pump or alternator is about as likely to strand you on a 10-year-old car as on one built with Lyndon Johnson was in office. Ignition systems became enormously more reliable once points went away, but the crankshaft position sensors on which modern ignition systems rely on can fail. Cooling systems on newer cars are generally much better designed for real-world heat extremes than those on old cars, but modern plastic cooling system components have a far shorter lifetime than their old metal counterparts. Modern serpentine belts automatically stay tight, but when the belt tensioners fail, everything comes to a screeching smoking rubbery halt.

The last two items on my list—clutch hydraulics and ball joints—aren’t as universal. Clutch hydraulic failure is usually age-related, and thus you don’t see it often on modern cars. And I include ball joints on the list mostly because if they fail, you lose control of the car, and thus you can’t afford to be wrong about it. They’re actually remarkably stout items on my 1970s BMWs, but if you google “ball joint failure,” you see photos of a variety of relatively late-model vehicles with a front wheel rotated 90 degrees and jammed up under the wheel well.

And obviously, there are common failures that are specific to vehicle make and/or model. I don’t road trip my vintage BMWs without checking the giubo—the rubber flex disc between the transmission and driveshaft—as well as carry a spare, as with age, they eventually crack. You can drive quite a way as they thump and smack the inside of the transmission tunnel on acceleration, but if they fail completely, the loose bolts can tear into the cover of the back of the transmission or break the ears on the transmission or driveshaft flanges.

This gets into the issue of “hard” versus “soft” failures. In a piece a while back, I made the distinction between “hard failures”—things like fuel pumps that pretty much either work or they don’t and instantly drag the car to the breakdown lane when it’s the latter—and “soft failures”—things that give you a lot of warning before they disable the car. The “soft failure” example I gave was the charging system. If the alternator or regulator goes bad and triggers the battery light, you can get many miles down the road—certainly off the highway, maybe even to a repair shop—before there’s not enough juice to fire the spark plugs.

Another item that’s not on my “Big Seven” list is wheel bearings. They do eventually wear, and are certainly an item to replace when systematically sorting out a car that’s sat for decades, but their failure mode is so soft that it’s practically a pillow with a Cashmere cover. Wear is usually caused by a combination of high mileage and loss of lubrication. Play will eventually develop between the bearings and the race they run in. This will allow motion along the axis perpendicular to rotation, which in turn will increase the wear.

Fortunately, wheel bearing failure is almost always announced by a ballsy-sounding rumble that’s pretty hard to miss. If the bearing is bereft of lubrication, it may also squeak or squeal. The pitch and severity of the sound should vary directly with vehicle speed but not engine rpm. The sound may change when the brakes are applied.

It’s usually easy to confirm a bad wheel bearing. Jack up the wheel, support that corner of the car with a jackstand, and spin the wheel. If the wheel is not a drive wheel—that is, if it’s a rear-wheel drive car and you’re checking a front wheel, or vice versa—the wheel should be easy to spin, and a rumble, if it exists, should be plainly audible. If it’s a drive wheel, though, this is more difficult, as the CV joints and the differential or transaxle are also turning, which makes it harder to spin the wheel fast as well as creates other possible sources for the rumble.

The other thing to check for is bearing play. The time-honored method is to jack up the car, set it on stands, grab the wheel at 6 o’clock and 12 o’clock, and push-pull-rock it back and forth. If you grab it at 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock, play can be due to a loose wheel bearing, but on a front wheel, it can also be due to anything in the steering chain. Play at 6 and 12 can generally only come from a wheel bearing.

A few years back, I wrote a piece about front wheel bearing replacement on one of my 1970s BMWs. Like many other vintage cars, these have a hub with inner and outer bearings, both of which have races that are press-fit into the hub and bearing adjustment that’s achieved by tightening a castellated nut just the right amount, then putting a cotter pin through the castles and a hole in the end of the stub axle. Replacement of these bearings is messy, but at least it can be accomplished without any special bearing pullers, as the old race can be banged out with a hammer and a punch and the new one pushed in with a hammer and a right-sized socket. On these cars, the front discs are attached to the insides of the front hubs, so replacing the discs exposes the bearings. Thus, if the bearings’ ages are unknown or if they show any or make any noise, it’s prudent to replace them when changing discs. I’ve thus replaced dozens of them.

In contrast, rear wheel bearings in my vintage BMWs are so long-lived that, after owning upward of 70 cars, I’ve never replaced one. There’s a little journalistic sleight of hand in that statement, though. Thirty-five years ago, my wife and I were vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard in a high-mileage 1973 BMW Bavaria. We were coming home from dinner when a storm and tidal surge moved in, and while driving along the low, exposed road that runs along the barrier beach between Edgartown and Oak Bluffs on the eastern side of the island, crossed through a low-lying flooded section where seawater was unexpectedly deep. After that, the right rear wheel bearing began emitting an ever-increasing rumble. I limped the car home and looked at it, but didn’t own the bearing pullers I own now, and I paid a shop to replace it. So I didn’t replace it, but someone else did.

However, I recently replaced the rear wheel bearings (one was rumbling) in my Winnebago Rialta (a VW Eurovan with a Winnebago camper body on it). This is a fairly common configuration where a rear hub and stub axle are pressed into the center section of a bearing, which in turn is pressed into a fixed housing. Thus, in two separate steps, the hub has to be pulled from the bearing, then the bearing pulled from the housing. I felt like I’d paid my debt to The Automotive Powers That Be, incurred from when I passed on doing the rear bearing on the Bavaria all those years ago.

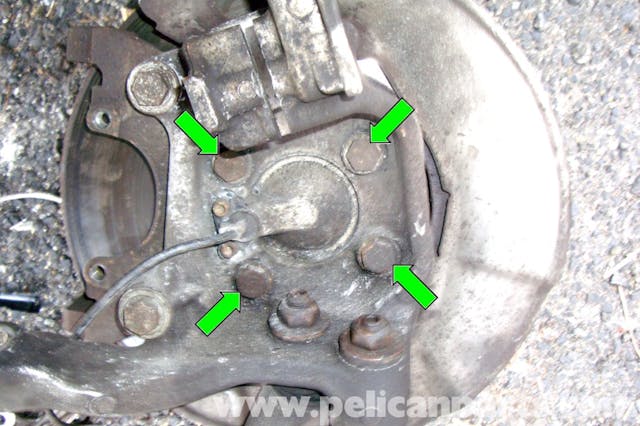

About 10 years ago, I replaced the front wheel bearings in a 1999 BMW E39 528i wagon I owned. They weren’t rumbling, but I was doing a front-end refresh including struts and control arms. I learned that the front wheel bearings on this car are a completely different design than on the older BMWs I’d had—they’re part of an assembly that bolts directly to the steering knuckle and has the hub directly integrated with it. That is, there’s no banging out or pressing in of bearings. The whole thing bolts on, and the wheel bolts directly to it. I also learned that access to the upper bolts is impinged on by the bottom of the strut assembly, so if you’re replacing the struts, it’s a good time to refresh the bearings. So I did.

When you replace these wheel bearing assemblies, you’re advised to also replace the bolts holding them in. The replacement bolts come pre-treated with a Loctite-like coating.

When I removed the E39 wagon’s old bearings, I was very surprised at the degree to which the Loctite on the old bolts sneered at my impact wrench and fought me every thread of the way. I needed to use a four-foot pipe on the end of a 3/4-inch breaker bar and grinch it off a sixth of a turn at a time, repeating this for each of the four bolts on both sides. I was exhausted by the time I was done. I made a mental note that this was a part I was unlikely to replace again if it wasn’t obviously bad.

And now, with that background, I can tell you about The Bad Wheel Bearing That Wasn’t.

I was driving my 2003 E39 530i—the car I routinely describe as the best daily-driver BMW I’ve ever owned—up to a recording session about 30 miles from my house when I began to hear and feel a bit of a rumble in the front of the car. It appeared to be coming from the left front wheel. I was surprised at how quickly the rumble came on, but it stabilized at a fairly low level. That is, the symptom wasn’t like loose lug nuts, which, as I described in this Hagerty piece about losing a wheel, can announce itself with a rumble that gets so loud and progresses so quickly that you have only five or 10 seconds before the wheel falls off. Even so, to be safe, I slowed down and pulled into the right lane and paid very close attention. The sound varied directly with speed and changed when I tapped the brakes, so even though the symptom wasn’t exactly that of a bad wheel bearing, it was close enough that I allowed those “soft failure” diagnostic neurons to fire and continued on to my recording studio appointment.

When I was done a few hours later, I wondered if I should play it safe and head to the nearest service station and ask them to throw the car up on the lift and check it out. The rumble, however, was still at a fairly low and constant level, so I continued onto the highway. I turned on my flashers, set my cruise control for 50 mph, and hugged the right lane. It got no worse on the drive home. I arrived at my house without incident, and pulled the nose of the car directly into the garage.

Since the problem was clearly a bad wheel bearing, I immediately went inside and jumped on my computer to get the part on order ASAP. I found that FCP Euro’s price on a front wheel bearing kit with a pair of German FAG bearing assemblies and the eight Loctite-coated bolts was over $300. Gulp! I began thinking about replacing only the bad bearing, and looking at prices and reviews of other less expensive aftermarket bearings, when I remembered the whole episode 10 years ago with replacing the wheel bearings in the wagon and how difficult those factory-Loctited bolts were to remove. A back injury I sustained last summer still has me hobbling around, and that kind of upper body twisting is a sure-fire recipe for relapse. Plus, there was the issue of the bottoms of the front struts being in the way of the bearing bolts. I realized that what I really needed to do was go out to the garage and verify beyond a shadow of a doubt that the bearing was actually the problem.

Believing the rumble was coming from the left front bearing, I intentionally began with the right one to get a baseline. I jacked up that corner, spun the wheel, verified that the bearing was quiet, grabbed it at 6 and 12, and verified that it was play-free.

I then moved to the suspected left front corner, jacked it up, and spun the wheel. It was noisy, though the noise was a little more clunky than rumbly. I grabbed the wheel at 6 and 12. Yup, play. Gotcha. Bad wheel bearing. I let the car down and began to walk back into the house to order the parts.

But then I had a thought—it was possible, though incredibly unlikely, that the problem could be loose lug nuts. After all, it was only a few weeks before that I’d swapped the car’s winter wheels for the summer ones. But, as I described in the wheel-fell-off article, for years I’ve been absolutely religious in my use of a torque wrench every single time a wheel is installed. I grabbed a half-inch ratchet handle and a 17mm socket and quickly checked the left front wheel’s lug nuts.

Four of the five of them were loose.

Holy crap.

I took the torque wrench and snugged down the nuts to the required 88 ft-lbs. Then, to quickly be certain this was the only problem, I jacked up the wheel again, spun it, and did the 6-and-12 push-pull. Noise and play gone.

Next, I checked the right front wheel. I was horrified to find that its lug nuts, while not loose, hadn’t been torqued down.

I checked the rears. Those were fine.

I have no idea how this happened. Due to the odd configuration of my garage, when I swap wheels, I’ll usually pull one end of the car in the garage at a time, jack it up, swap both wheels, let it down, torque down the nuts on both wheels and inflate both tires to the correct pressure, pull the car out, spin it around, and do the other end. I don’t know if, between doing the back and the front, I got interrupted by a phone call, or if this was some artifact of the fact that I make accommodations for working with a back injury in many ways, which may include stopping when I feel sore.

I’m convinced it was that one snug nut that saved me. Had that one loosened up, I would have had only a brief window before all hell broke loose like I’d experienced before.

My lug-nut vigilance has now officially increased to hyper-paranoid. I went out and double-checked the lug nuts on my wife’s car (they were fine).

So, yeah, the symptoms of a bad wheel bearing are still a rumble that varies with speed, and wheel bearing play is still discernible by doing the 6-and-12 push-pull-rock thing. But when a rumble first appears, stop and check your lug nuts. If you don’t, a wheel bearing’s “soft failure” can turn hard in the quickest and most dangerous way imaginable.

***

Rob’s latest book, The Best of the Hack Mechanic™: 35 years of Hacks, Kluges, and Assorted Automotive Mayhem is available on Amazon here. His other seven books are available here on Amazon, or you can order personally inscribed copies from Rob’s website, www.robsiegel.com.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Rob. Question, why were you putting snow tyres on and pulling them off of off all four wheels. Don’t the snow tyres only go on the driving wheels? Now I have see a few examples of some people from up north put them on the front wheels of rear wheel drive cars but I figured they were just not to bright Yankees.

Why would you only want two of your four to have traction in the snow? “Not to bright,” hmmm…

Optimus, you would not want snow tyres on the front of a rear wheel drive car because the studs would cause you to loose traction on dry pavement. Second snow tyres with their aggressive tread would cause a vibration in the steering of the car, similar to the mudder tyres on off-road vehicles. So no on a two wheel drive rear wheel drive car you do not want snow tyres on the front unless you live in an are where the snow stays on the roads from late fall to late spring.

I will let your comment speak for itself : )

I think maybe you haven’t driven on modern snow tires, studded or studless. There’s never any vibration from modern snow tires, as long as they’re balanced properly, just like any other modern tire. Snow tires are made for stopping, turning, and going. If you only put them on your rear wheels they aren’t going to help you stop nor turn nearly as well as if you put them on all 4.

I’m not sure where you live, but many states don’t allow snow tires with studs, because of the damage to the roads. But on the subject of 2 vs 4 snow tires, when my wife got her first Prius, many years ago, the all season tires it had were absolutely useless in snow. So I ordered up a pair of dedicated snow tires from an online vendor. They CALLED me, saying they wouldn’t sell me just two tires, they needed to be on all 4 wheels, the traction differential was that great. I’ve never been without dedicated snow tires since then, the car will go just about anywhere in snow – and it is just front wheel drive.

The biggest determining factor in the usage of snow tire is consistent low temperatures. The compounds are different and snow tires have more traction on dry surfaces once the temperature gets within swinging distance of freezing.

Studs are illegal in many places and aren’t required to have effective winter tires (they help ice, but that’s where their advantages end).

Considering 70% of your braking is done with the front wheels, along with 100% of your steering, I’d consider 4-corner winters “vital” equipment.

Not snow tires, winter tires. And yes, I put 4 of them on my Boxster each November and pull them off in March or April. Not much point in being able to go if you can’t turn or stop.

It’s not the acceleration traction that becomes an issue with only 2 snow tires on the ground. It’s the DE-celeration. If braking hard ( like in, fer’ instance, trying to save yourself from sudden death in a panic stop) the two snow tires have appropriate grip, the all season ones don’t and will continue to slide their merry way into oversteer or understeer depending on your car (and situation). It is thus EXTREMELY dangerous to only mount two snow tires. It’s what us in the Rocky Mountains call a “Very Bad Idea”

Whew, crisis averted indeed! Here’s my process: when I remove a wheel, in addition to the star wrench or impact gun, I place six things on the floor of the garage – five lug nuts and a torque wrench (with the appropriate socket). I do not walk away from the reinstalled wheel until I’ve used that torque wrench to ensure the lugs are cinched down to spec. I do not put the torque wrench away until I’m positive that all wheels that’ve been removed have been sufficiently tightened. Since I started this tactic 50 years or so ago, I’ve never lost so much as a lug nut (and I see them often alongside the road – especially fancy chrome ones from expensive wheels).

Rob, I absolutely love reading your articles.

But there’s another lesson to be learned here as well: “Look for the easiest and cheapest fixes first (even if it can’t POSSIBLY be that)!”

A veteran mechanic explained that to me while I was in the middle of tearing apart a dashboard for something that turned out to be a cheaper, easier, right-there-under-the-hood fix.

Still, it seems that I need to be reminded of that one just about every time I lift a wrench, so I’m certainly not casting a stone.

Great point, John – that same thing has caught me plenty of times. It seems I should learn more quickly!

I had a 99 Buick with cartridge style bearing and hub where the bearings developed play (noticeable in the handling) before ever exhibiting noise

Also I have forgotten to tighten lug nuts at least once in my driving career and that wheel will make one helluva racket and vibration before anything bad happens – although I still recommend double-checking the tightness

Glad it was actually an easy fix. Though getting loose nuts is a little scary.

I’ll see myself out now. “^)

😂

I’m not sure about the wheel bearings giving you a warning. Years ago I was driving to college on the highway at ~65 MPH in my 84 Audi Coupe GT and it felt a little vague. I moved the wheel back and forth a little to see if it was just in my mind and the back right dropped, my brakes were hitting the ground. The back wheel had fallen off due to a bad bearing. Never made any noise or vibration. The weight was so far forward on that car that it went for a while without the back ever dropping with no tire. I never did find the wheel or tire, could have been gone for miles.

Glad to read that the last lug nut didn’t come loose. I swap studded snow tires on and off each year on three cars; two of mine and my sister’s car. Having lug nuts come loose is something that gives me concern each year, but god forbid that it happen to my sister. So I usually go around each car TWICE with the torque wrench to make sure I haven’t overlooked one wheel. The lug nut torque spec on my sister’s car is 115 ft-lbs (’20 Grand Cherokee), so I hope she never has to change a flat tire – she lives two hours away.

I very much enjoy Rob’s writing. Even the back story is fun, educational, and entertaining. Keep it up.

Good story. One thing to remember is that whenever you install alloy wheels, and particularly those that don’t have conical lug nut seating surfaces, you should recheck the lug torques after 50 miles of driving. Almost no one ever does it, but lug nuts can and do occasionally loosen, and us humans make mistakes. This simple check can prevent a problem like the one you experienced.

Good advice. I am friends with a guy who owned a tire store (since retired), and he hammered that into me for years. It’s now kind of second nature to me to re-torque after 30 and then 50 miles. Some people might think I’m a little bit anal about torquing lugs, but I’ve never “thrown a shoe” since beginning driving in the late ’50s!

Google the meme “What’s this light on the trailer wheel mean?” Sorry i couldn’t paste it.

News you can use. Good article, Rob, and thou art no “hack” mechanic. This is the sort of thing we’d like to see more of in Hagerty, fewer here’s what your MustangCamaroFerrari’s worth. Thank you, sir.