Deciphering Massachusetts’ “Right to Repair” ballot question

A somewhat confusing automotive question is on the ballot in my home state of Massachusetts. It’s Question 1, the “Right to Repair Law, Vehicle Access Data Requirement Initiative (2020).” One side is arguing that it’s simply plugging a loophole in an existing “Right to Repair” law to include telematic (wireless) data, while the other side claims it’s an irresponsible data grab that jeopardizes personal safety. Which is it?

To both sides, and to the consumer, it’s ultimately about money, but the money comes wrapped in other issues. The term “Right to Repair” (sometimes abbreviated as “R2R”) is both general and specific. In a broad sense, it refers to a number of consumer rights initiatives where owners of goods—from automobiles to farm machinery to electronics—push for the right to take these products somewhere other than the dealer to be fixed at a reasonable cost, and that’s where vehicle manufacturers (VMs) push back, touting trademark issues and trade secret concerns. As cars have gotten more and more complex, these battles generally aren’t over nuts and bolts—they’re over hardware, software, access to data, and the money that that brings. No VM is asserting you don’t have the right to change a flat tire or replace a wiper blade yourself.

To understand the confusion over the 2020 R2R ballot question, it’s necessary to understand why cars have onboard diagnostics, what the Massachusetts 2012 R2R ballot question was, why it was then voluntarily adopted nationally by the VMs, and what is meant by “telematic data.”

A Brief History of OBD-II

Beginning in the mid-1970s, in order to comply with the increasingly stringent standards of the Clean Air Act, engine management systems in cars became more complex. By the end of the 1980s, nearly all cars had electronic fuel injection, an oxygen sensor, and an Electronic Control Unit (ECU) to manage it all. California, and then the feds, soon mandated that VMs include On Board Diagnostics (OBD) that monitored the health of emissions-related systems and reported malfunctions to the driver. These early OBD systems typically had a “blinky light” that was actuated by an arcane series of steps such as clicking the key to ignition, mashing the gas pedal three times, and then counting the number of flashes. In addition to OBD, VMs began including a connector into which a dealer-only computer could be plugged for their own diagnostic and repair purposes.

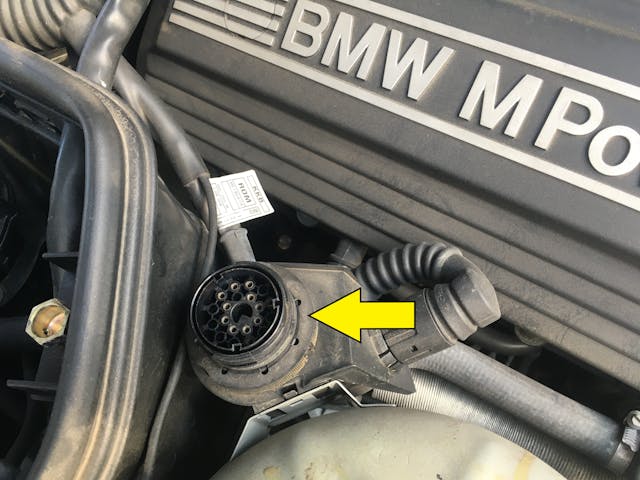

As part of the 1990 Gore-Waxman amendment to the Clean Air Act, Congress required that all auto VMs include a standardized 16-pin OBD-II diagnostic port presenting standardized emissions-related digital messages that any repair shop or individual could access and get information on the cause of an emissions-related failure. We may all rail against the “Check Engine Light” (CEL) when it comes on, but the fact that we can buy a $30 OBD-II code reader, plug it in, and read, for example, that we have a misfire in cylinder #2, and run out and buy a stick coil and replace it ourselves (or have the corner garage do this) is a triumph of “right to repair,” even though at that time it wasn’t spelled with two capital Rs.

After 1996, with the industry-wide incorporation of OBD-II, the dealer-only proprietary connectors generally went away, and both the standard OBD-II messages as well as proprietary marque-specific messages were transmitted over the 16-pin connector (the proprietary messages are presented on one of the connector’s vendor-optional pins). But in order to read the proprietary messages, you needed the dealer-only diagnostic computer. That is, the Clean Air Act mandated that you have the right to repair emissions-related systems, but it didn’t mandate that the manufacturer share all diagnostic data, only emissions-related diagnostic data. This distinction continues to this day: If you buy an inexpensive OBD-II code reader, it will only read the standardized emissions-related messages, but if you buy something model-specific that calls itself a “scan tool,” it should read at least some of the model-specific messages. Note that, as cars have gotten more complex, the number of control modules in each car has increased dramatically. There may be modules for heating and A/C, lighting, and transmission control, and an OBD-II code reader may not read fault codes from any of them, as they’re not emissions-related.

The 2012 Right to Repair Law and 2014 MOU

In 2012, Massachusetts put a “Right to Repair” question on the ballot that mandated that VMs provide the means to access all diagnostic data, not just the standard OBD-II emissions-related data, by 2015. It passed overwhelmingly, with 86 percent voting for the initiative. The ballot question was then superseded by a Massachusetts state law. Faced with the possibility of dealing with similar initiatives in other states, in 2014 the VMs, represented by trade organizations such as the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and the Association for Global Automakers, compromised with Massachusetts and signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), agreeing that by 2018 it would meet the requirements and provide the means for accessing diagnostic data not just in Massachusetts but in all 50 states. In theory, this means that independent repair shops have the means to access the fault codes and other diagnostic information from all control modules, not just the emissions-related codes.

It’s instructive to actually read the MOU. It seems to offer five avenues for diagnostic data sharing. The first describes sharing information with scan tool manufacturers:

“Each manufacturer shall provide diagnostic repair information to each aftermarket scan tool company and each third party service information provider with whom the manufacturer has appropriate licensing, contractual or confidentiality agreements for the sole purpose of building aftermarket diagnostic tools and third party service information publications and systems.”

As a do-it-yourselfer, I wondered: If VMs have been required since the MOU went into effect to provide the ability to decode the previously-proprietary diagnostic information, where are the new generation of affordable scan tools that allow folks like me to access this newly-available diagnostic info on my BMW? The answer appears to be that making the diagnostic information available and deciding that there’s a market for a DIY marque-specific scan tool that does much more than an OBD-II code reader are two different things.

In addition, the MOI says that, by 2018, VMs must make diagnostics available via one of the following three methods:

- A personal computer and a non-proprietary vehicle interface device that complies with the Society of Automotive Engineers SAE J2534 [that’s the 16-pin OBD-II connector]

- An on-board diagnostic and repair information system integrated and entirely self-contained within the vehicle such as a service information system integrated into an onboard display.

- A system that provides direct access to on-board diagnostic and repair information through a non-proprietary vehicle interface such as Ethernet, Universal Serial Bus or Digital Versatile Disc.

The fifth diagnostic data sharing avenue is subscription-based technical updates:

A manufacturer of motor vehicles sold in the United States shall make available for purchase … the same diagnostic and repair information, including repair technical updates, that such manufacturer makes available to its dealers through the manufacturer’s internet-based diagnostic and repair information system or other electronically accessible manufacturer’s repair information system. All content in any such manufacturer’s repair information system shall be made available to owners and to independent repair facilities in the same form and manner and to the same extent as is made available to dealers utilizing such diagnostic and repair information system. Each manufacturer shall provide access to such manufacturer’s diagnostic and repair information system for purchase by owners and independent repair facilities on a daily, monthly, and yearly subscription basis and upon fair and reasonable terms.

I list all five of these because they make it very clear that the intent of the 2012 law and the 2015 MOU is to allow independent repair shops (and, to some extent, individuals) the same diagnostic capability as the VM.

Exempted from that agreement, however, were several things. One was “diagnostic service and repair information necessary to reset an immobilizer system or security-related electronic modules.” This was to address concerns that providing wider access to this information could increase vehicle theft.

But the other major exemption in the 2015 MOU, one which the VMs reportedly lobbied hard for, is telematic data. “Telematics,” at its most basic, is a vehicle’s ability to transmit data to a remote computer where it is stored and analyzed. Telematics really began with fleet management, where a trucking company could outfit its vehicles with GPS, have those locations sent back to a central server via a cellular link, and thus keep track of where they all were. But with personal vehicles, it had its start when, nearly 25 years ago, General Motors introduced its OnStar system that detected an airbag deployment and alerted first responders to come to the accident scene. Other subscription-based systems followed, generally marketed around security, safety, and rapid response in the event of accident or need for roadside assistance.

The exact language of the telematic exception in the 2015 MOI is as follows, with bold added for emphasis:

“With the exception of telematic diagnostic and repair information that is provided to dealers, necessary to diagnose and repair a customer’s vehicle and not otherwise available to an independent repair facility… nothing in this chapter shall apply to telematics services or any other remote or information service, diagnostic or otherwise, delivered to or derived from a motor vehicle by mobile communications… For the purposes of this chapter, telematics services shall include, but not be limited to, automatic airbag deployment and crash notification, remote diagnostics, navigation, stolen vehicle location, remote door unlock, transmitting emergency and vehicle location information to public safety answering points and any other service integrating vehicle location technology and wireless communications.”

And that brings us to…

The 2020 Right to Repair Ballot Question

Although it’s estimated that 90 percent of new vehicles sold have some sort of telematics, it’s specifically excluded from the 2012 R2R Law and 2015 MOI, so currently these telematic data streams are accessible only by the vehicle manufacturer and their dealers. The stated intent of the 2020 Right to Repair ballot question is to close this telematic loophole—to do what OBD-II did for emissions-related diagnostics and what the 2012 Right to Repair Law attempted to do for all vehicle diagnostics and make the telematic data available to you or to an independent repair shop. The ballot question is pretty straightforward. It reads:

This proposed law would require that motor vehicle owners and independent repair facilities be provided with expanded access to mechanical data related to vehicle maintenance and repair.

“Starting with model year 2022, the proposed law would require manufacturers of motor vehicles sold in Massachusetts to equip any such vehicles that use telematics systems—systems that collect and wirelessly transmit mechanical data to a remote server—with a standardized open access data platform. Owners of motor vehicles with telematics systems would get access to mechanical data through a mobile device application. With vehicle owner authorization, independent repair facilities (those not affiliated with a manufacturer) and independent dealerships would be able to retrieve mechanical data from, and send commands to, the vehicle for repair, maintenance, and diagnostic testing.

“Under the proposed law, manufacturers would not be allowed to require authorization before owners or repair facilities could access mechanical data stored in a motor vehicle’s onboard diagnostic system, except through an authorization process standardized across all makes and models and administered by an entity unaffiliated with the manufacturer.

Predictably, those in favor of the ballot question include a coalition of independent repair shops and auto parts chains. Domestic and foreign auto VMs are vociferously against it.

So who’s right?

In my opinion, the “Yes on 1” side is slightly misrepresenting their position, but the “No on 1” side is outright lying about theirs. Here’s why:

The ballot question says “mechanical data” not once, but five times, and that access requires the owner’s permission. The question does not include access to personal data, such as location. This is crucial, because the “No on 1” organizers are blatantly fear-mongering the question as a personal security issue. Their political organization, named “The Coalition For Safe And Secure Data” has created a series of creepy sensational ads. One shows a young woman, stalked while walking alone to her car in a parking garage, with the breathy voiceover: “If Question 1 passes in Massachusetts, anyone could access the most personal data stored in your vehicle. Domestic violence advocates say that a sexual predator could use the data to stalk their victims, pinpoint exactly where you are, whether you are alone, even take control of your vehicle. Vote no on 1. Keep your data safe.” I’m sorry, but what a lying load of malarkey. Upon examination, the supposed “no” endorsement by a domestic violence group isn’t even for the Massachusetts ballot question; it’s from an unrelated initiative in California.

I’ll agree, though, that the “No on 1” folks does have a point when they say, “We already voted on Right to Repair, you already have it, and independent repair shops already have what they need,” at least as it applies to diagnostic data that’s available through the OBD-II port and via other means. However, they lose all credibility with me with the scare tactics and with the pretense that it’s about “safe and secure data” instead of maintaining the status quo of telematic data being available only to the VMs whose money is behind “No on 1.” I’d have more respect for them if they just told the truth and said, “Look, we’ve spent millions on these diagnostics; it’s not fair to ask us to just give them away.”

Looking at the “Yes on 1” side’s argument, the fact sheet on massrighttorepair.org reads: “More than 90 percent of new cars transmit real-time repair information wirelessly, and independent repair shops will soon have limited or no access. Vehicle manufacturers are increasingly restricting access to car information. This means car owners are steered toward more expensive dealer repair options. It’s your car—shouldn’t it be your right to access the information you need to repair it without having to pay high prices at the dealer? Massachusetts voters voted 86 percent in 2012 to require car companies to make available repair information and diagnostics. But now big auto is using the next generation of wireless technology to get around the law and shut out independent repair shops. That’s not what we voted for. It’s your car, you paid for it. You should get it fixed where you want.” In my opinion, although it’s a bit hyped-up from a marketing standpoint, this is all valid, and the ads from the “Yes on 1” side are largely truthful.

There is, however, a “but.” Recall that, although the 2015 MOI excluded telematic data, it included an exception for diagnostic telematic data. For example, if a car began hesitating, ran worse and worse, and finally died, and if real-time telematic diagnostic information analogous to an automotive EKG of the failure in progress (more than simply stored fault codes) was sent off the car to a dealership, the VM is supposed to have also made that information available through a plug-in connection to the data port. So it begs the question: What, exactly, is the telematic “mechanical data” that independents feel they need access to? I discovered the answer, but it’s a bit arcane.

The #2 donor to the “Right to Repair Committee” is the Auto Care Association, an industry trade group representing independent repair shops and manufacturers of parts and tools. In 2013, ACA and others formed the Telematics Task Force (TTF). If you dig online, you can find the TTF’s papers and presentations. Note that the Task Force, being formed by trade groups representing independents, is unabashedly pro-independent, with a mission statement that vows, “To empower vehicle owners to direct the services of their vehicles to locations of their choice.” Their papers, however, are pretty well thought-out. One is a December 2014 white paper that discusses standards and usage scenarios for the following different kinds of telematic data:

- Driver personal data (including name and current vehicle location)

- Driving behavior data such as acceleration, steering, and braking

- Forensic (accident-related) information

- Annual motor vehicle inspection data

- Diagnostic data

- VM proprietary information such as versions of software in the different control modules

- Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) data (GPS, radar, sonar, yaw, pitch, accelerometer, etc.)

- In-vehicle infotainment data

The white paper includes a reference to a standardized telematic vehicle data format and a “common vehicle gateway” to allow access to the data. Additional detail on this is contained in a 2015 Telematics Task Force presentation. The paper also discusses what it refers to as vehicle “prognostics”—the ability to analyze data from multiple cars, identify trends, look at data from a particular car, and predict a failure before it happens.

The conclusion of the white paper is very telling:

The “if the dealer gets it, we should get it” rule of thumb has served the industry well, and there is no reason it cannot be continued into the telematics age. In fact, for the most part, the rule does not have to change at all, except for the addition of two new concepts.

- There [should be] no fundamental difference between the diagnostics the VMs have agreed to provide, hooking a scan tool to a vehicle connector, and remote diagnostics, hooking up to a vehicle via radio signal, whether that signal travels 3 feet or 3000 miles.

- If the dealer has VM access to prognostics through telematics, aftermarket suppliers need to have access to the same information so that it can be provided to aftermarket repair facilities.

… The information the aftermarket needs is the same as what VMs have already agreed to provide through a wired connection, with one exception.

Telematics brings with it prognostics, a kind of diagnostic process based on vehicle data that can only be gathered using telematics. The MOU that was signed one year ago states: “With the exception of telematics, diagnostic and repair information that is provided to dealers, necessary to diagnose and repair a customer’s vehicle, and not otherwise available to an independent repair facility via the tools specified in… above, nothing in this agreement shall apply to telematics services or any other remote or information service.” We submit that prognostic information derived from telematics is diagnostic data not provided through the vehicle diagnostic connector. In the final analysis, we find that the definition of the telematics data we need includes any data provided directly or indirectly to a car owner or a new car dealer through telematics systems for the purpose of performing maintenance and repair on vehicles. This includes any diagnostic, prognostic, or maintenance related information generated by a telematics transaction.

It is our desire to look for productive ways to work with VMs to continue to raise the level of service offered to our mutual customers. We feel that telematics is the natural evolution of this process. In addition to augmented diagnostic abilities, we also recognize that prognostic, diagnostic and maintenance warning capabilities built into these vehicles should be such that vehicle owners can decide who will receive this data and ultimately who will service their vehicles.” [I bolded the type for emphasis.]

When presented this way, it’s not at all surprising that the VMs offered their “we’ll give you wired diagnostic data through the OBD-II port, but telematics are off the table” compromise in 2015, and that independents apparently immediately began plotting another run at the issue. It looks to me like members of the Telematics Task Force simplified their argument by reducing that list of data types into just “mechanical data” and “personal data,” said they’re only addressing “mechanical data” to head off privacy concerns, removed the esoteric references to “prognostics” as the reason for needing access to telematic data, replaced it with a broader “extend R2R to include wireless data” argument, sprinkled it with a dash of “it’s your data, you should decide who gets it” language, and six years later, their white paper popped out as the 2020 R2R ballot question.

I intend to vote “yes” on Question 1. However, I’ll admit that I think the “mechanical data” thing is a bit of a red herring. I think that this has less to do with diagnostics and repair (e.g., vehicle has already broken) and instead has everything to do with creating an opportunity to market for maintenance. What independents are most concerned about is that there’s currently a closed-loop electronic relationship between the vehicle owner and the dealer/VM, and it’s only going to get worse. The car’s mileage and service needs are being monitored by its embedded software and can be transmitted telematically to the dealer/VM. If an oil change is due, or the tires are nearing the end of their projected service life, or the check engine light comes on, the dealer can get that information, call, email, or text the owner to schedule a repair appointment, or that can be done right on the screen in the car’s console. In contrast, an independent shop currently has no way to break into this loop, and those folks desperately want it. They want you to schedule an appointment with them instead of the dealer, if you so choose.

I’ll admit that I cringe at the possibility of a Minority Report-style future—“Hello, Mr. Yakamoto, welcome back to the Gap. How did those assorted new tank tops work out for you?”—where every independent repair shop can beam targeted marketing pablum into my car. But, in fairness, the dealer/VM can essentially do this now, and the ballot question says that access would require your authorization.

Regarding the actual architecture of the proposed “remote server with a standardized open access data platform,” even some of those who support the R2R initiative have reasonable questions about the design and timeframe. James C. Owens, the deputy administrator for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), weighed in on the matter in a letter to the Massachusetts legislature. He called the initiative’s data access platform requirements “vague,” and expressed concern that, given the initiative’s 2022 target, developing a system that keeps vehicle control isolated from diagnostics and fully testing and debugging it by then might not be possible. Personally, I don’t consider this a showstopper. I look at how it played out in 2012, where a ballot question turned into a Massachusetts state law, which turned into a compromise with the VMs that carried a delay of several years in implementation. The ballot question, if it passes, will likely be a similar starting point for a negotiation with the VM industry.

I think that the 2020 “Right to Repair” Massachusetts ballot question is pretty much what it claims to be in terms of being an extension of the 2012 R2R law to include telematic data. The wiggle room in “pretty much” is that the access to telematic data is likely as much an opportunity to market repair services to you as it is an actual conduit for repair-related information. Still, in an environment where boundaries are constantly being drawn over data ownership, saying that this is your data and not the dealer/VM’s and that you have the right to determine who has access to it is a good thing.

***

Rob Siegel has been writing a column (The Hack Mechanic™) for BMW CCA Roundel magazine for 34 years and is the author of seven automotive books. His new book, The Lotus Chronicles: One man’s sordid tale of passion and madness resurrecting a 40-year-dead Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special, is now available on Amazon (as are his other books), or you can order personally-inscribed copies from Rob’s website, robsiegel.com.