Smithology: Losers of the Autobahn

The parking garage was dark and quiet. Every other car was asleep for the night—Camrys and SUVs of all flavors, the panoply of splendor seen every year at Monterey. But there is always a difficult moment, as Churchill said, in any grand endeavor.

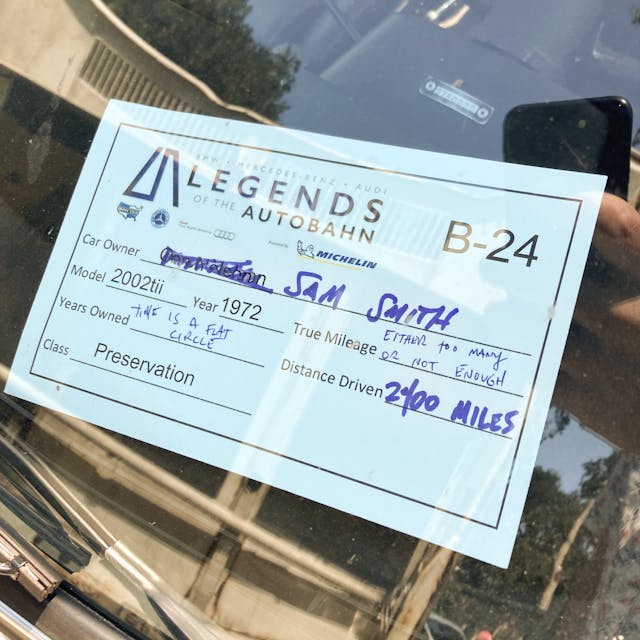

One does not simply drive into a judged car show in California’s most moneyed peninsula during the most glamorous week of the automotive year. You bring your A-game or stay home. People prepare for months for an event like this, and so had we. Starting with my 1972 BMW 2002tii, a scraggly patchwork of rust and bad dreams, a former parts car only recently dragged back to life.

The actual concours prep took time. Nooks and crannies were toothbrushed with a fresh coating of dirt and grime. Details were made period-correct: Are those bolt heads aligned ex-factory? Is the carpet mildew redolent of era-appropriate funk? Was that form of oxide actually allowed by the laws of 1970s chemistry? Does the jagged rust hole in the rear fender allow a grown man to reach into the trunk and lightly grope a rear shock tower, as any discriminating roadside individual might have done in period?

It was nearly midnight. A pair of white cotton gloves rested on the BMW’s nose, fingertips brown from inspection passes. Owen’s voice echoed from near the front bumper, next to a three-foot pile of dirty rags.

“Did you count the greasy fingerprints on the hood? Fewer than ten per square foot, we lose points.”

“Twice. I added a few during the drive out, but they didn’t match the factory books, so I tweaked the shapes at a truck stop in Bako. Isopropyl and Q-tips.”

“All that’s left is the headliner mold. The spots in the vinyl? You spray them with preservative?”

I snapped, exhausted. “Look, this is a judged class. Do I look like a loser?”

Owen sighed, more patient. “We’re both tired. Let’s get some rest.”

He was right, but I couldn’t stop. He spent the next few minutes carrying dirty rags to the Dumpster across the street. When he finished, he paused, concerned.

“Take care of yourself, okay? Don’t stay up too late.”

I looked down at my hands. They held a small bottle of dime-store carnauba wax. I had spent the past 20 minutes buffing the car’s 16 corroded and torque-smeared lug nuts, careful to leave no residue on the wheels.

“I can’t. Work to do.”

There is always work.

***

I slept fitfully. In the garage, at dawn the next morning, the car fired instantly, settling into a high and smooth idle. I nudged my left shoe past a dangling remnant of floor carpet and onto the clutch pedal, then patted each of the eight cracks in the dash for good luck.

We rolled into the Monterey County Fairgrounds at 7:15. A coliseum, already packed with champions. That Monterey fog hung in the air, humid but cool, condensing on windows and chrome.

Legends of the Autobahn: a show for Audis, BMWs, and Mercedes-Benzes. (Porsches used to appear at this thing, but the Porsches packed up and found their own golf green, across town. This is how Porsches work.) Owen found me after I parked; he was chipper, having slept. Our friend Ben was with him. Both men had helped me build the car, helped preserve its flood damage, part of the crew of friends who molested the car back to greatness after years of outside storage in the Northeast.

“I don’t often say this,” Ben said, “but the pressure here is intense. Think of how your life would change if you won. You could retire on the proceeds. The fame would launch ships.”

“I know I couldn’t take it,” Owen said.

I looked around, uneasy. “I owe you gentlemen more than you know.”

We walked the green, looking at cars. There were dozens, modified and stock, M3s and M4s and RS4s, even a restored Mercedes W123. By the time we had made the rounds and circled back, an hour or so later, the crowd around my car was overwhelming. Hundreds of people. Voices echoed through the crush.

“What is it?”

“I love it.”

“Are those door panels?”

“Did he really drive here from Tennessee?”

“Is this even a BMW?”

“What is that smell?”

An older woman and her richer boyfriend walked up. She made a face. “Does it even have an engine?”

“I think it drove here,” said the boyfriend.

“I don’t know,” she said. “It’s kind of awful.”

My heart sank.

What did I miss? Was it that moment where I neglected to tenderly buff the safety wire holding together the rust-eaten rear fender lip? Were the wheels not sufficiently spattered in spilled bearing grease? What about the copious oil leaks? Given half a chance, the front crank seal alone would have left gallons on the grass at Pebble Beach. Shouldn’t that count for something?

“Kind of awful” was an intentional slight; the car was full awful and she knew it. Obviously a bitter old crone, struggling with her place in the universe.

I found the great Bill Arnold. A legend in vintage BMWs, a restoration and service icon from Northern California. Bill has long been a serious man, a stern philosopher. When I saw him at the show, he was eyeballing a particularly clean 6-series. He waved a hand at my concours class—Preservation—quoting Kant.

“Science is merely organized knowledge.”

“Easy for you to say,” I said. “You don’t have your life’s work on this show field.”

“You couldn’t pay me to risk it all like that.”

The sun poked through the clouds. I nudged Bill with an elbow, pointing to my car’s class. “You’re smarter than I am. What’s that gem at the end of the row? Looks like the only real competition.”

“Oh, man. That’s Kaelin Thompson. Lord, he’s good. Shows up every year with the nastiest machine in the class. That’s a 2000tii Touring, the hatchback, originally delivered in France, easily the least envied car in town. Nearly wins every time, has been on Fallon and Colbert and Space Ghost Coast to Coast.”

“I knew this was serious.”

“There’s a quart of tetraethyl lead on display in the trunk, unopened, new old stock. That stuff gives you cancer. Don’t know where he got it. Hell of a touch.”

I quietly surveyed Kaelin’s car. White, like mine, but more thoughtful in detail. The quarters and trunk were rusted through, the rubber seals dried up. Most of the extensive corrosion had been artfully rattle-canned a nonmatching shade of white, and the interior stank of wet basement. As a final touch, Thompson arrived dressed in period. What presented at first glance as a Southern California kid in his twenties, fresh out of bed, was in fact a calculated assemblage: Where does a grown man even buy a Hawaiian shirt patterned in anatomically correct drawings of nude women? Who has the foresight to grow a Seventies-style Tom Selleck lip rug for a single car event? He stood by the car nonchalant, the confidence of a contender, both of the scenery and apart it, like a background character in Scooby-Doo.

The judges would swoon. I cursed myself for not doing better. Bill saw my face.

“Don’t be so hard on yourself. What’s important is that you’re here, and that you had the courage to enter.”

“I wonder sometimes, Bill.”

“Happiness is not an ideal of reason,” he said, gesturing to our surroundings, “but of imagination.”

And on that note, the judges appeared. Out of the mist, walking with somber purpose, clipboards in hand.

My knees went weak.

Concours judging is not a pastime for the careless. One of the judges, a marque expert named Jeff Hecox, I have known for years. His eyes were edged with cautious recognition, balancing our acquaintance with the gravity demanded when judging the best of the best.

My blood pressure began to fall, slowly but surely. A view of the engine was requested. Rust had long ago separated the hood from its supporting frame; raising the panel caused the whole assembly to wave drunkenly through the air. No crafted moment of pedigree could match that spontaneous display of class. I felt good. The metal moved under my hands like a thoroughbred horse, or perhaps a wacky waving inflatable tube man.

Both judges scrawled dispassionately on their clipboards.

“Tell us a little about the … let’s say ‘car’,” Hecox said. I began a monologue: How I’d bought the BMW by accident. The scholarly repair process that both orbited abject disinterest in structural originality and critical use of aluminum foil. I digressed into historic footnote, quoted Chaucer, referenced scientific papers of note. The narrative closed with a discussion of the rectangular steel tubes now serving as my 2002’s rockers, which led organically to a careful cataloging of the car’s various odors.

When I was done, Hecox pulled me aside. “I’m not supposed to say this,” he whispered, “but what an achievement. I haven’t seen anything this patently smelly since Sharknado 5: Global Swarming.”

“Thank you,” I said. “It’s an honor.”

The awards ceremony was scheduled for the end of the day, hours away. As the judges left, Thompson walked up. He crossed arms for a moment, sober. I had not yet seen him smile. We shook hands.

“You put on a hell of a show. But in war, there is always a loser.”

“Coming from you,” I said, “that means a great deal. And your shirt is magnificent.”

He was taken aback by the compliment—a rare kindness in a cutthroat field. But pros hide well their emotions. His eyes flickered briefly in recognition, unsettled, then reflashed into stoic wall.

“Thank you. I got it at Penney’s.”

Then came the wait.

There is always the wait.

***

Late that day, after the sun had set, I pulled back into that same parking garage, exhausted. For an instant, the car had been made perfect, obsessed over and crafted for display. And now it was again mere transport.

I shut off the ignition, and the engine grumbled to a stop. Relief.

An emcee had announced the winners. Trophies were awarded from a small stage, the crowd hushed. Both Thompson’s car and mine were in the game, but our names were not called. Top Preservation Class honors went to a machine that one bystander called “the nicest BMW 1600 on the west coast.”

But few battles are ever logical. Confusingly, when I took a closer look, the winning car seemed spackled with flaws. The rocker panels were solid and original, not peppered with holes. The rear-seat covering was pliant and plush, neither broken down nor cracked with age. Most of all, there was a clean and rust-free tub—no hasty repairs, no awful welds staving off structural collapse.

The paint was even glossy.

The choices people make, I tell you.

Either way, that’s in the past. And this is how human endeavor works. We aim at grand goals. When we fail, we simply reimagine our dreams and re-enter the coliseum with greater steam.

So I took the first steps in that direction. I climbed out of the car and walked to the rear bumper, carefully retrieving a few water bottles from the trunk. Then I opened each bottle, one at a time, pouring their contents over that rusty hood and through the holes in the fenders. In a moment of particular inspiration, I even lifted up the remnants of the driver’s-side carpet and poured through a gaping rust hole in the floor.

Fail again, as Beckett said. Fail better.

There is always the trying again.