Smithology: I’m building another Caterham. WOULD YOU LIKE TO KNOW MORE?

Hi! Are you one of those people who loves learning about the strange corners of the new-car universe? Do you like quirky little machines steeped in history and performance? Have you ever wondered what life would be like if you threw off all your cares and bought an eminently affordable adrenaline fire hose brimming with speed and feedback?

You’re in luck!

Welcome to an FAQ on the Caterham Seven. The car once known as the Lotus Seven, and a mainstay of English speed culture for decades. It is a 1960s throwback capable of outrunning supercars. It is also one of the oldest—and yet most satisfying—new cars on the market.

Why should you care what I think? Well, I’ve tested more than a few Seven variants in both America and Europe. I’ve visited Caterham’s home base, near London, and interviewed company engineers. Several years ago, I owned and partially rebuilt a late-model Seven. Last year, while employed by another outlet, I helped build a different Caterham from a kit. (Sevens can be delivered factory-built in other countries, but in America, the car is available only as knocked-down parts. It is perhaps the most famous and most copied kit-car in history, after the Shelby Cobra clone.)

Finally—last but not least—I’m about to help build another Caterham kit, with a family member who has long wanted one. It is a 2021 Caterham Super Seven 1600, the first example of this model in America.

Call what follows a primer for the happy insanity of Seven ownership. Call it a bunch of tiny-British-car questions you didn’t know you had. Call it a moderately engaging discussion of a machine that has been part of the new-car firmament since the Rolling Stones were young enough to be sober.

Just don’t call it short.

***

Okay, I’ll bite. What’s a Caterham Seven?

Tiny thing. Like a coffin with fenders. Born in 1957 as the Lotus Seven. So named because it was the seventh Lotus designed by company founder Colin Chapman. The Seven was Chapman’s first truly successful road car, a groundbreaking marriage of period formula-car technology and practical compromise.

The average Seven weighs 1200 pounds and offers four wheels, two seats, a modest little four-cylinder, and not much else. The car lacks anti-lock braking, traction control, electronic stability control, and power steering. Even the heater and top are optional. It exists for the purpose of offering speed and feedback to two people and possibly a small dose of luggage.

Sevens live on the virtues of light weight, simplicity, and doing more with less. The steel-tube spaceframe is covered in sheet aluminum. Most of that aluminum is flat. Imagine a Formula Ford with a passenger seat. If you don’t know what a Formula Ford is, imagine instead what might happen if a world-famous midcentury genius and lovable motorsport lunatic designed a road car with great prejudice. (Good practice, really.) Then imagine that said lunatic unleashed this car on the public at a wholly remarkable and deeply affordable price.

One name change, a long list of updates, and several decades later, Chapman’s car is still with us. A small miracle, miraculously undead.

Wait. That old Lotus buggy? They’re making those things again?

They never stopped making them! Chapman famously whipped up the original Seven as a way to help fund his race team. The car sold well, but he grew bored with it. (Colin Chapman trivia: Like many geniuses, he grew bored with everything. Quickly.)

Chapman wanted to move the company upmarket; rightly or wrongly, he saw a kit-built road bullet as something of a hindrance. In 1973, he sold the Seven’s production rights to a passionate Lotus dealer named Graham Nearn.

This name sounds vaguely familiar.

Nearn’s outfit was called Caterham Cars, after its location, a small town in Surrey. Over the next few decades, he kept the Seven alive through irrational and joyous faith. When he died in 2009, the entry-level Seven made only slightly more power than in the 1960s, but the car featured a host of improvements aimed at durability and comfort. There was also far more speed, if you wanted to pay for it.

Not that the base car was, or is, slow. The slowest Seven on offer in 2009 made around 130 hp and would nearly pace a contemporary Porsche 911 to 60 mph. It cost only slightly more than a new Volkswagen Golf. The fastest Seven of that year hit 60 in 2.9 seconds and carried more horsepower per pound than a Bugatti Veyron. No matter how much power you ordered, any Seven was a babbling brook of feedback and sensation, caffeine on the hoof.

In 2021, Caterham’s cars are basically the same, just better.

Neat! What does it feel like? Orgasm on wheels? Elbows in the breeze cheerio, like a Morgan?

Glad you asked! Much of the answer depends on model year and spec. That said, generally speaking:

Light and delicate but also durable. A cross between a suit of armor with an engine and a very large and particularly feisty pair of pants. A lovely state of chassis tune married to a nearly complete lack of anything even passing for a filter means that every drive leaves your undergarments fizzing. The car moves immediately when you ask and feels distinctly out of time with the rest of the universe. The cockpit is broken into two person-sized holes, each maybe an inch wider than each of the car’s seats, with a transmission tunnel between. The steering wheel and rear axle might as well be stitched to your bones.

Chapman specialized in feel and proper treatment of a tire. Early Sevens thus recall old-school Lotuses—long-travel suspension, surprisingly decent ride quality, often more power than grip. (But also a great deal of grip.) “Modern” Sevens—which is to say, anything built in the last 40 years or so—sacrifice a bit of comfort and steering delicacy for handling prowess. They’re still a hoot, just different.

Must be quick, right?

To a point. Being an open car first laid out in the 1950s, the Seven offers the aerodynamic drag of a small house. Below 70 mph, even a base model will win a lot of stoplight races. Above that speed, the car’s drivetrain fights a losing battle with the resistance of passing air. Even the most potent models—more than 300 hp these days—are significantly tamed at triple-digit speeds.

Thankfully, life is not a race. Autobahns exist only in Germany. Smart suspension geometry and low weight go a long way. If you can’t sling a Seven down a back road at ludicrous velocity, you may not be cut out for motion.

Bonus: Sensation overload exists even in traffic. Blame wind blast and feedback, and the fact that you’re low enough to throw a hand in the breeze and fondle the pavement.

So kind of like a Miata, then? Or a motorcycle with a second seat. Or a Corvette kart, or that KTM X-Bow thing, or an Ariel Atom?

Sort of! Also not at all.

The cliché paints a Seven as a motorcycle on four wheels. (Physical abuse! Landscape making out with your face! Dead bugs the grout between your teeth!) That’s hogwash; motorcycles are motorcycles, and cars are cars. The sensations are vastly different, not to mention a bike’s sense of full-body immersion.

I have road-raced Miatas. I have track-tested more supercars than I can count. This isn’t any of that. It’s just … a Seven. Neither new nor old, history nor now. Simply itself.

Not that you can’t see how motorcycles come up in the discussion. The ideas parallel. You get out of the thing after a good, hard stomp down a back road and feel physically drained, at one with the essence of travel. But mostly, it’s just Car. Distilled and pure. Vaguely redolent of another time, but deeply rooted in the present. Not to mention wonderful.

I don’t want some old-think business! There are safer, smarter, and more modern ways to go fast.

True! That’s the march of progress! We are now blessed with a host of machines designed to deliver minimal Pure Car and maximum performance.

Decades ago, Sevens were widely viewed as budget supercars; the world saw the model as the bonkers alternative to a Ferrari at a fraction of the price. These days, unless you’re spec’ing up one of Caterham’s hard-core track specials, the edge of the envelope has moved on. You buy a Seven because you like the story and the idea behind the thing.

And the fact that five seconds to 60 mph is still just far from slow.

Go back to the Ariel Atom and that KTM. Aren’t those good and modern? Why would I do this instead of that?

Each is a barrel of laughs and fast as hell. Like the Seven, each offers a pure experience, no electronic driver aids. Unlike the Seven, neither is offered with a top or weather equipment, making them even more joyously simple to live with. But don’t get to thinking those cars aren’t also outdated; an Atom is basically 1990s technology, and the KTM was first drawn up in the mid-2000s. The Ariel is made of steel tube and lacks body panels. Water and stones blast into the cockpit and collect in your nether regions. And while the KTM is a carbon-fiber monocoque, with a modern turbocharged four-cylinder and an available twin-clutch gearbox, it isn’t street-legal in America.

Not to knock these cars in any way. The experiences are just vastly different. The KTM is for serious track-day people. The Ariel is a more abusive version of the same idea but older and road-legal. A Seven is just … what did I say above? A Seven.

I just looked at the configurator. Seems expensive. These cars are simple. What if I design and build one myself?

You can! The chassis is almost entirely straight tubing; if you can use a MIG welder without creating a mountain of boogerslag every two seconds, you can probably build yourself a Seven. People tackle this project so often, books have been written on the process. One of the engineers behind the current Corvette engineered and built a Stalker—another Seven-type car—with six-cylinder BMW power. My friend Emile Tabb, a former professional race mechanic and amateur road-racer, built himself a Seven from little more than an old RX-7 motor and a few off-the-shelf body panels.

If that whole process sounds awful and you don’t feel like engineering a car from scratch, there’s also the vast world of Seven clones. Quality is all over the map and often a step below the ex-Lotus original, but these cars do exist. (This site’s editorial director famously owned a South African-built Seven clone. A failed chassis weld caused a crash at a track day. Long story short: Be careful.)

Let’s say I want to buy one of these little rats. Where do I start?

As with any project, the first step is budget. Used Seven clones can be had in decent shape for $15,000. Used-Caterham prices vary heavily with spec and location, but the cars generally run from around $20,000 to just under six figures. New-Caterham cost varies with exchange rate, but the most affordable models now start in the high thirties. Price rises when you add power, carbon bits, track suspension, and so on.

About that: The internet shows a zillion different models, new or old. Superlight this, Roadsport that, blah blah blah. How in blazes do you choose?

Depends on what you want to do with the car, and what you have to spend. The great and strange genius of Chapman’s work is how adaptable it is. Want a bare-bones track weapon? The last five decades have offered a host of options, multiple powertrains, a wealth of available factory performance upgrades. Plan on touring? You can spec a car with a larger cockpit, softer suspension, a heater, comfy seats. The variations are so broad as to be virtually endless.

Caterham, like Lotus before it, has continually evolved the car. A model that began life in the 1950s with a live rear axle and pushrods has since been built with everything from inboard front suspension to a sequential manual gearbox. A few rare Sevens feature an independent rear. Generally speaking, most of these changes have improved the beast without sacrificing personality.

Below, a brief overview of the changes available throughout the years, and how they feel, in the general order that the Caterham factory made them available. Most of these features were at one point optional; some, like the long cockpit, are now standard Caterham practice.

Long cockpit: A few extra inches of length, and thus legroom, over the original “S3” Lotus Seven. The room is welcome, and the wheelbase bump also adds a bit of high-speed stability.

De Dion rear suspension: A smartly done reengineering of the Seven’s original rear layout, halfway between a live axle and a truly independent rear. Now standard on American-market Cats. Live-axle Sevens feel more alive but can be a handful on lumpy pavement. The de Dion is a nice compromise and noticeably improves ride quality.

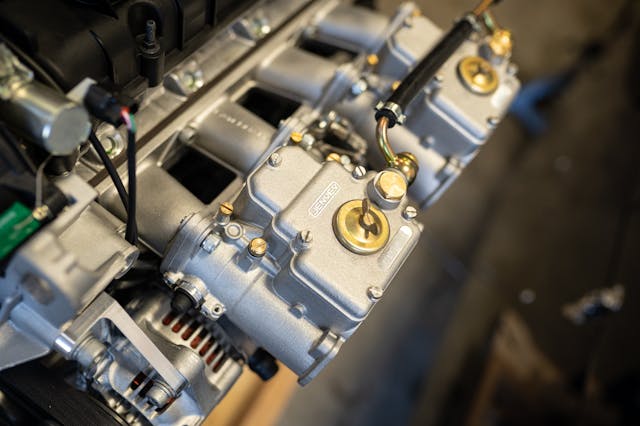

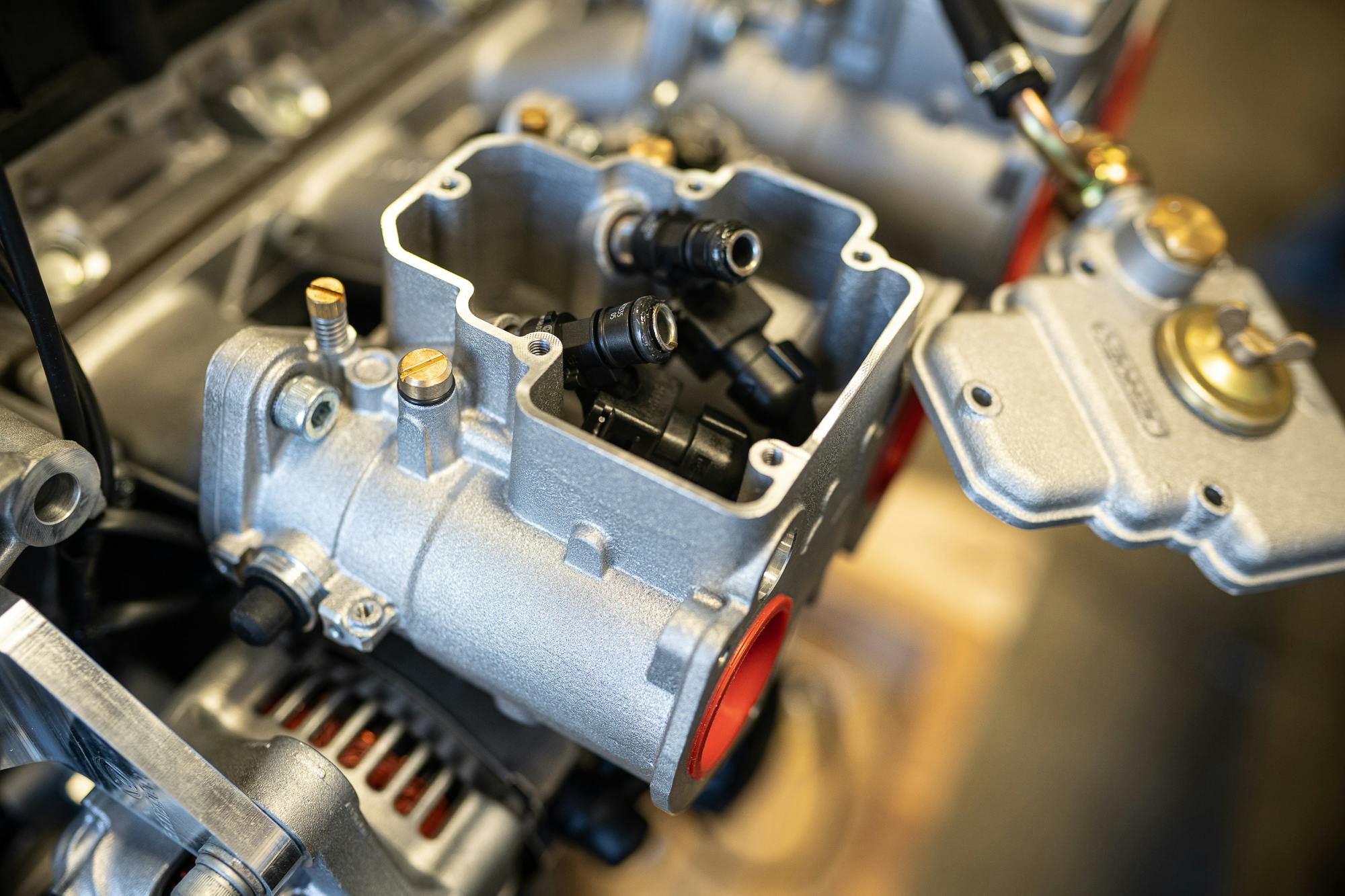

Fuel injection/twin cams: Almost without downside, and available on one optional engine or another since the 1980s. Federal regulations meant that most American Sevens wore carburetors until the early part of this century.

Low floors: Drops the car’s floorboards around two inches at the seat mounts. Good for tall drivers or those who simply want more cockpit room. The chassis shown here is so equipped; the dropped floors are the black bits beneath the basic blue tub.

“Wide” body: A.k.a. “SV” in Caterham-speak. A chassis 4.3 inches wider and 3.2 inches longer in wheelbase, offering a significantly larger footprint and a more comfortable cabin. Best for those taller than about 5-foot-10 or wide of hip. Comes with a wider pedal box, useful for big feet. (Many people drive Sevens in socks, and not because it’s more comfortable. Chapman was apparently an elf.)

“Wide track” front suspension: Developed for the Caterham 21 but fitted to many standard-body Sevens after factory engineers used one as a mule for the 21 and liked the result. The wider front track helps balance the car and reduce understeer while increasing high-speed stability. There’s no real downside save cosmetics—wide-track cars can look a little apelike at certain angles.

Independent rear suspension: Available only on the now-discontinued and track-focused CSR model. Designed by Multimatic, the Canadian engineering firm that built the last Ford GT. Generally agreed to be overkill, especially without big power, but it works quite well.

Sequential six-speed gearbox: Best for track use, though people do run them on the street. Immensely quick to shift, though not calibrated for comfort. The standard five- or six-speed manual is fine for almost everybody.

Engines: [Cue maniacal laughter.] The list is long. Most American Sevens extant wear some form of Ford Kent; this pushrod engine, designed in the late 1950s, is both historically correct for the car and emotionally resonant. Its age can aid registration in some states, allowing newer Sevens to be titled as vintage machines. (You see a lot of Caterhams titled as Lotuses, and legally.)

Still, engine choice has long been up to the builder. Sevens exist with Lotus twin-cams, Toyota twin-cams, rotaries, Haybusa-based V-8s, on and on. The current Caterham factory answer involves a range of modern Ford four-cylinders of Sigma or Duratec extraction. Most distributors can help source a powerplant.

That’s … a lot. Not sure I know where to begin.

You’re not alone. Anecdotal experience holds that a minority of Seven buyers know exactly what they want; the rest have not been lucky enough to test-drive a wide variety of models and configurations and thus have zero clue. The best answer is always to be slightly more conservative than you think: Err on the side of a more comfortable and slower car than your heart screams for.

Perhaps it sounds crazy to buy a tame version of a wild idea. Trust me on this, however: The more the car resembles a normal automobile, the more likely you are to drive it and enjoy it. That 300-horse snotrocket with shell seats and all the spring rate will be huge fun over an apex, but you might not want to mainline insanity on your Sunday run for ice cream.

Hush your face. I want the biggest motor I can swing.

I mean, this is understandable, but really, you don’t.

I can handle it. I am a driving god! I have a spine of steel. I drive flat out.

Great! The point stands, though.

Why?

Bonkers Caterhams are fantastic—silly speed whenever you want, and enough power to vaporize the rear tires on a whim. But unless you spend your entire life at track days, Sevens of this nature are generally overkill, unpleasantly abusive outside short jaunts. More to the point, their extremely light weight allows for immense capability, and you can only use a fraction of that performance on the road. Think hypercar problems: Who wants to idle down the road at the speed limit?

Even the Caterham factory admits that its cars are best for road use with around 150 horsepower. That works out to just over 8 pounds per pony, or roughly the same power-to-weight as a brand-new, 463-hp Ford Mustang GT.

Alright, table that idea for a bit. What’s it like when you take the plunge on a kit?

You get crates! Usually by truck freight, somewhere between six months and a year after your order. One crate holds the engine, another holds the body, and there’s a third for various subassemblies. The rest of the car is contained in a surprisingly small collection of cardboard boxes.

Unpacking one of these kits is a strange brand of bliss, a cross between What Have I Done financial reckoning and nerdy adult Christmas. If you order what Caterham calls “full weather equipment”—basically just a simple top with side curtains, as you’d find on an old Jeep or an MG TC—that stuff will come preinstalled. The chassis is painted, wired, and lightly plumbed. The rest is up to you.

Sounds fun. Didn’t Jeremy Clarkson put one together in an office in a weekend or something, on Top Gear?

First off: Never trust what you see on television.

Second: Build time varies. Heavily. Caterham claims that one moderately skilled human can assemble a new Seven in 80 to 100 hours. Realistically, however, it hangs on more than you. Certain parts of Cat assembly are less than intuitive, even if you’ve built or restored cars before. The factory assembly manual is useful but often vague where you want specific and specific where vague would do. Clearances between components are often insanely tight, the result of one company reengineering one car to take a dozen different engines and countless cosmetic layouts over the course of half a century.

And finally, just when you think you have a bead on things, you will run into a missing part and have to park the whole process. (New Caterham kits are occasionally absent small and unique pieces of hardware or trim, most of which have to be requisitioned from the factory’s parts depot in England.)

It’s fun, though. Huge fun. Assuming you take none of it too seriously and resolve to enjoy the process.

As does a sense of humor.

(If we should ever happen to meet in a bar somewhere, and each of us has a beer in hand, feel free to ask me what I meant by that last sentence.)

(Do not do this, by the way, unless you have nowhere to be for 30 minutes and thoroughly enjoy the sound of a man yelling about the joy-pain of British cars of any stripe.)

Wait. I thought you said this was a real car?

Sort of? Was Colin Chapman a real carmaker? Is an English cottage industry really an industry? What’s the airspeed velocity of an unladen European swallow? If you open Schrödinger’s box and put Jim Clark’s bones inside, does the now-dead cat give a toot?

Real car, sort of. Normal, no. This is part of the draw, but it is also entirely possible to get wound up about it. To own, build, or even just maintain a Seven is to bear witness to the thousand slings and arrows that the British-car business has long inflicted upon its patrons. You either find that amusing, or it makes you want to fly to England just to throw a bunch of warm beer on a sheep and yell about the colonies.

“Seven people” have a saying for those moments of marque-specific quirk: “It’s part of the charm.” The joke being, of course, that said charm is not always charming. Sometimes, you just want to install a differential without shaving off your knuckles. Maybe you’re putting the car together and find yourself wondering just why the English individuals who packed your kit for shipping—who do this exact job every day of the year—somehow missed the three critical and unobtainium bits that you must now have shipped from across the Atlantic and cannot find anywhere in America, at any price.

Again, a Seven is sort of a real car. It’s also a long and almost heroically vibrant update of a 1960s British elf, and a Lotus elf at that. It comes from a nation that has allowed a carmaker like Morgan to thrive. (And bless them for that. But … they still make cars out of wood.) Logic is less than the currency of the realm.

The Morgan comparison is apt, though. Think of a Seven as similar: not so much automobile as feeling distilled into the shape of a vehicle. When you buy one, you do it for the experience and the romance and the nuttery, and the machine itself is simply a bonus.

More than half a century of selling the same car. You’d think they’d have a handle on it.

Well, sure. You’d also think that an island nation the size of Alabama wouldn’t try to take over the world with wooden ships and funny hats, but hey, who’s counting?

Touché.

Good allusion. Owning a Seven of any stripe is like fencing with England’s id.

Any dealers you like? Someone to guide me through the process of ordering or finding one of these things used?

We’re fond of a few Caterham specialists: My first stop would be either Josh Robbins at Rocky Mountain Caterham in Denver, or Bruce Beachman at Beachman Racing outside Seattle. Both men are reformed club racers and old hands at all things Seven. There’s also Chris Tchorznicki, at Sevens and Elans in Florida.

Robbins and Beachman are Caterham importers; Tchorznicki no longer sells or imports new Sevens, but he’s a legend in the business, and he occasionally brokers or sells used examples. Either way, none of these guys will lead you astray.

That’s nice. What if I just haunt Facebook Marketplace instead?

Be prepared to wait. Caterham builds a relative handful of cars each year. The waiting list is months long, and the factory runs at capacity more often than not. On top of that, Seven people seem to have a habit of rarely selling their cars. Long story short: Demand often outstrips supply.

I bought mine used, for the record. The search consumed more than a year, and even then, I eventually caved, settling for a spec slightly off from what I wanted in exchange for condition and convenience.

Seems logical. What’s the catch?

Most Seven owners don’t drive their cars much. The market bears this out—most Caterhams for sale are low-mile, even by classic-car standards. Many have sat a while and need sympathetic refurbishing. Some were built by those without much mechanical sympathy. Mine had fewer than 2000 miles on the clock, and I still spent a winter tearing the car apart to prep it for use and sort gremlins.

Why would you buy one of these things and not use it?

Who knows? But if I had to guess? I’d say the people who don’t drive their cars … bought the wrong car.

Not the wrong vehicle. The wrong version of a vehicle. Sevens can be hugely versatile, but they’re not for the faint of heart. Most people think they want the legend plus modern steroids—the numbers king, with unpadded race seats, abusive suspension, and all the power in the world.

In the right environment, that stuff is lovely. But few of us live at ten-tenths. And a bonkers Caterham is a lot like a supercar: The histrionic and abusive ones are the most work to use, and they get driven the least.

Which is fine, of course. But who doesn’t want to see pavement more than 15 minutes from their house? I tend to think miles are more fun than waxing fenders with a diaper.

Not that there’s anything wrong with diaper-waxing.

Depends on what’s in the diaper, I guess? The simple truth is this: Many folks think they’re Seven people. Few really are. The cars are a unique bag of pluses and minuses, and not for everyone.

Recall the motorcycle analogy for a moment—people often buy a bike for the life they want, not the life they have. Sevens are the same, and fraught with the quirks of any car built around vintage ideas: Hardware can loosen through everyday use; driveline and cosmetic bits occasionally have freakishly short lives; repair is not always straightforward. The hassle of owning and using an impractical, bare-bones device engineered before Richard Nixon was president is too often just outside the patience span of most car people. Even most vintage-car people.

If you are one of the rabid true believers, however, you don’t need to be told. You have known that fact since the dawn of your existence, and you can’t explain why. You adore history but refuse to live life looking backward. The more you read about Colin Chapman and Lotus, the more you want a piece of the great man’s work. You like driving more than you like most things, and above all, you believe in purity, simplicity, and the legs of a good idea.

Still, you won’t really know until you meet the car. Until someone gives you a right-seat ride or hands you the keys. That day when you climb out of a tiny aluminum shoebox, bugs in your chompers, and sit there wondering, above all, how to get the next fix.

Purity and legs. There are worse things to believe in.

You ain’t kidding.

Now if you’ll excuse me, there’s a funky little British anachronism in my shop, and I have to go see a man about some crates.

***

Sam Smith is an editor-at-large with Hagerty. He came to the company after an eight-year stint at Road & Track, where he set a record as the only person in the magazine’s history to drive a Formula 1 McLaren, track-test a Dodge van in Japan, and mock a wild bear in the Arctic in the same year. He lives in Tennessee with a ragtag collection of tools and a very patient wife.

Follow him on Instagram and Twitter: @thatsamsmith