Smithology: College people are dangerous

I wrote this story in college, exactly 20 years ago. It has never been published. I stumbled onto the draft last week while cleaning an old hard drive.

I met Carter and Pranka while trying to figure out what to do with myself—before figuring out how to make a living writing about something I loved, before ending up at places like Road & Track, Esquire, and Hagerty. The two men taught me something about honesty, how being into cars didn’t have to mean fitting a mold or dumbing yourself down.

Twenty years is a long time, but I still recognize the guy at the keyboard. I did, however, take the liberty of rebuilding and focusing his story a bit, to help it get where he wanted. Call it a small thank-you for two people I should have thanked long ago. —SS

“Do you think this is bulletproof?”

Carter picks up the six-by-six glass block. I scratch my head.

“I mean, do you have a problem with firefights at the shop . . . toilet?”

“Not really?”

“Isn’t the remodel mostly done? Those blocks are going in anyway, right?”

“I just think it’d be cool,” he said, smiling, “to have a bulletproof bathroom.”

A percussive laugh echoes in the back of the building. The source appears a moment later, in a ski cap and dark coveralls, hands covered with grease. Pranka squints at the block, shrugging.

“I dunno. Bulletproof toilet. Seems important.”

Carter chuckles. Under his desk, lying on the floor, James gives a huffy little wuff-wuff in response. James is the shop dog. James does not like to be left out.

I am in college. Carter is the only real employee here, though I get paid to help out. Pranka—his first name is Mike, though Carter never says it—imports high-end Japanese phonograph cartridges for a living. That job is full-time and yet does not keep him from stopping in regularly to say hi to James or discuss stereo equipment or simply poke around and shoot the shit.

The empty shell of a Ferrari 250 TdF rests in the corner. The stripped Lancia Fulvia a few feet away has not moved in months, but a photo placed on its hood shows the car at Sebring in some ancient running of the 12-hour. The building is maybe two and a half cars wide, in a quiet part of Midtown St. Louis, an old brick storefront on an otherwise empty gravel lot.

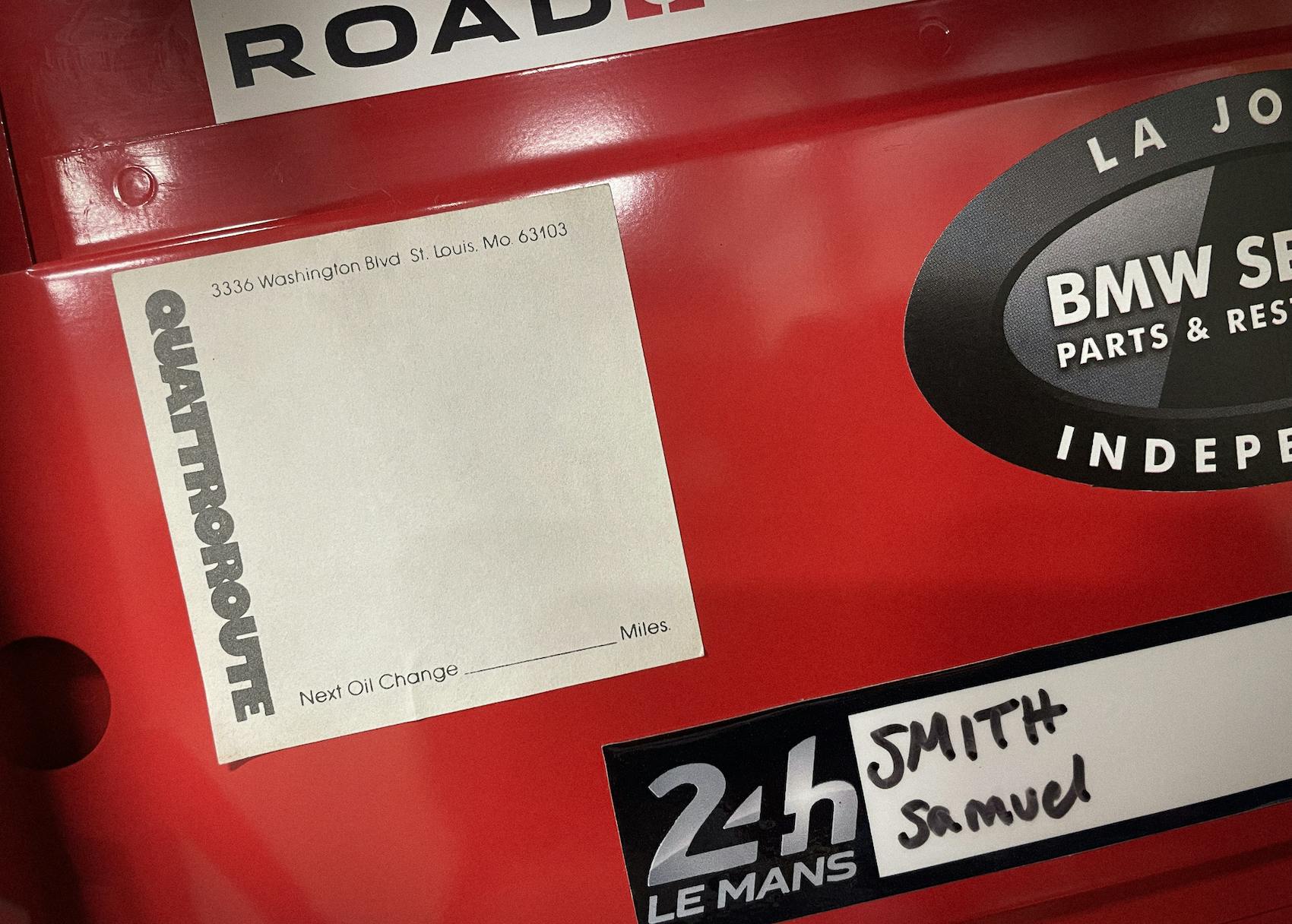

The shop is called Quattroroute. The name is a respelling of the Italian for “four wheels.” Carter started the place for service and restoration work, primarily Alfas, back when ordinary people still drove those cars regularly. (“We would do head gaskets every spring,” he told me. “Like clockwork.”)

Everyone knows a shop like this. Most people do not know Carter. He has hair like Einstein on Saturday. In his spare time, he thinks about roll centers and balljoint flex and designs single-ended vacuum-tube amplifiers of no more than one or two watts. One of those amps lives on a shelf in back, fed by an old CD player without a case, playing Billie Holiday through an old wooden speaker horn originally built for theaters.

Carter has tried to teach me how those amps work. I am, however, a 21-year-old English major, and I do not comprehend electricity beyond the water-flow theory, and it is hard to concentrate on that anyway because my life is mostly dishwater beer and reading and loud punk-rock shows at scuzzy St. Louis dive bars and there is only so much time in a day for the nuances of things like electron movement.

He knows that, though, so he keeps trying.

***

I moved to St. Louis three years ago. If the Berlina did not appear immediately, it seemed to. An early Seventies model, Alfa’s top-shelf four-door, one of those Giugiaro shapes where the lines work in pictures but ring a little off in reality. I would catch glimpses of the car in traffic or headed the other way on crowded streets, logging new details each time: Bits of the dark-blue paint are peeling away; the rear window wears a sticker from the New City School; the left rocker panel has rusted to nothing; the right one is even worse; the windows fog in rain.

Like most Italian cars, Alfa Romeos are not known for rustproofing. There is a little-known conspiracy theory that calls this intentional. A shadowy cabal of international financial elites, this theory says, is working to establish iron oxide as a new and highly inflationary fiat currency.

Fun idea. Also lightly ridiculous and easily shot full of holes. Like (zing!) an old Alfa.

For a college kid from Kentucky, that Berlina sighting was hard to parse. I had never lived in a city and had to that point known Alfa Romeos only as Sunday-car-show victims, rarely used and often waxed. Was this, I wondered, really how people used funky old cars? The Alfa appeared in all weather and four seasons—what kind of loon would keep a pile like that alive for commuting?

Trying to find out was like chasing a ghost. I’d pop through the Central West End and see the car sitting at a light in the oncoming lane, then find it gone by the time I turned around. I’d be fiddling with the radio in some jammed-up downtown turn lane, hear a familiar snarl, and look up just in time to see a flash of blue duck around a corner and out of sight.

Location was the only common thread—the Berlina was always in the same two or three neighborhoods. Where it evinced light disregard for posted limits.

Naturally, that was Carter.

***

It is late January, lunchtime. I have not seen the Alfa in weeks. Class has ended early. A nasty accident has snarled a major intersection near campus. Leaving school, I take a roundabout path to avoid this, cutting a few blocks farther east than usual.

Then, on Washington, it’s there. Parked, in a gravel lot, next to a building on which someone has painted a large and familiar graphic of a snake eating a man.

Check for traffic, downshift, hook a U-turn, slide to a halt on the handbrake. Just inside the door is an Alfa Spider with the hood up. A man in a cardigan and khakis is changing the plugs.

I walk up slower than I want to, introduce myself, try to be polite, try not to gawp through the open door.

He is wary for a minute, then warms, inviting me in. The shop is basically one room, with two-story ceilings and wooden rafters. Recorded piano jazz tinkles up from the back. The rest of the space is consumed by cars and period photos and dealership signs. A Lancia Aurelia. The stripped body of a 1940s Alfa 6C. A half-reassembled GTV, gold-and-white cloverleaf badge on the rear pillar.

An aluminum V-12 block sits in a hallway like a doorstop. I resist asking, then cave.

“A Tour de France works 250,” he says. “Trintignant drove it.”

I knew the name from books but had never heard it pronounced aloud. Maurice Trintignant was a Formula 1 driver—Ferrari, Maserati, Cooper, Vanwall, Lotus, BRM. He won Le Mans in ’54. Those are Ferrari parts, just sitting on the floor, worth more than a new Porsche.

The tour consumes the next half hour, multiple stops in a small space. A flow bench and shelves of shop manuals. A Lancia Appia, this little bowler-hat sedan, stuffed into the parts room. A rust-free Alfa Giulia Super, freshly painted, to replace that dying Berlina. I ask how long he’s been in St. Louis.

“I worked for Hill and Vaughn for some time as an engine builder, but I’ve been here about ten years.”

“As in . . . Phil Hill and Vaughn?”

“Yeah! He was a cool guy.”

This seems unbelievable, and so I do not initially believe it. Weeks later, however, he would pull from his desk a small photograph of a younger Carter, a man with a mustache and much shorter hair, perched on the seat of some brass-era car by the side of a road. The details suggested California. The man next to him was . . .

Well, Phil. Because Carter does not make stuff up.

This country has given the world just two Formula 1 World Champions: Mario Andretti, in 1978, and before that, Phil, in ’61. The journalist Denise McCluggage called him Hamlet in a helmet, a habitual over-thinker and sweet guy who happened to possess monstrous talent. There was also Hill and Vaughn, the Los Angeles restoration shop that he co-founded in retirement, a place that all but invented automotive restoration as an art form, half fabrication shop and half research library staffed by curious romantics.

I was born more than a decade after Hill stopped driving professionally. Still, you read the stories, certain people come to mean certain things.

“Yeah,” Carter says. “That was the coolest part. When I went to work there, he was my hero. At the end, after three years of day-in, day-out employee stuff? Still my hero.”

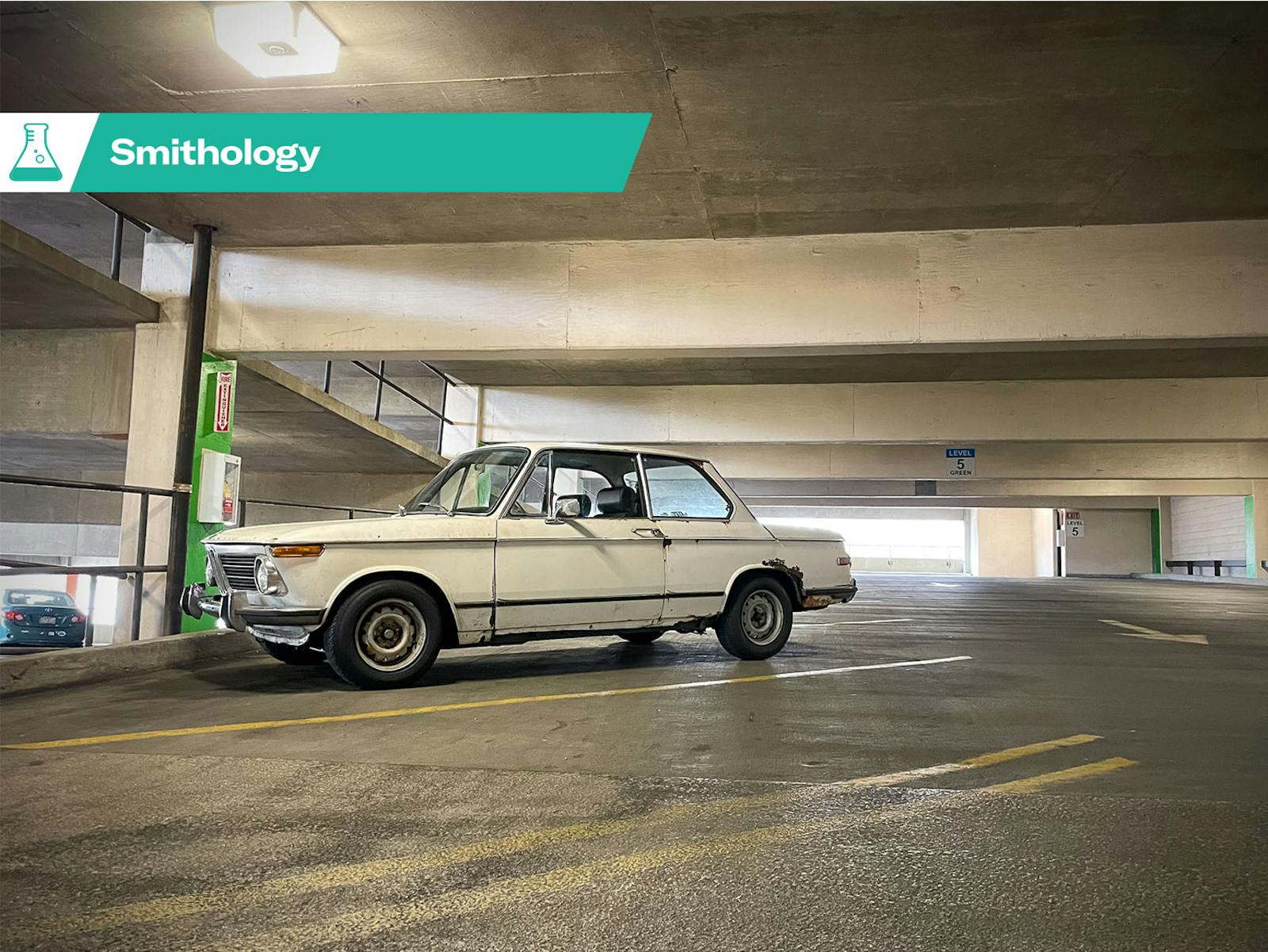

We talk for another 30 minutes. He mentions the Futa Pass and 1950s Alfa development drivers casually, as if I know who or what they are. He asks about the BMW 2002 I arrived in. Toward the end, there is a job offer. I take it without thinking.

I walk out with my head in the clouds, drive home on autopilot. It is like leaving true north.

***

He turns the block over in his hands.

“So . . . if I wanted to find out . . . ”

James raises his head.

” . . . do you know anybody with a gun?”

Pranka shrugs again. “Ask Sam. He’s in college. College people are dangerous.”

It has been 20 minutes since anyone has done anything even remotely like work. I lean against a wall, hands in my pockets. “I don’t have a gun?”

Pranka blinks, then starts over, deadpan. “So. We could get Sam’s gun—”

Carter’s face lights up.

Me: “I don’t even know how to gun?”

“—and we hold up the block.”

Me: “Oh.”

“—and then we just have to shoot at it.”

A detail seems missing.

“How,” I ask, “would it stay in one place?”

Pranka makes a face. “You could hold it.”

“I could hold it,” I repeat.

“Isn’t that what I said?”

“You mean, like, in front of my face.”

A finger points at my nose. “Exactly.”

Carter erupts into laughter, then stops, record-scratch. “Wait! John Vollman has a gun!”

I glance above his head. No lightbulb.

Pranka: “Is this the guy you . . . ”

Carter leans back in his chair. “. . . Yeah!”

Me: “Wait, what?”

“I gave this city cop a ride once, in a Ferrari we restored. He loved it. Giggled the whole way. He looks down at one point and we’re doing 80—this is on Locust—and he asks how fast I usually get, at the end of this street.”

I blink a few times.

“I figure, what the hell, I’m already doing 80, right, and he hasn’t said anything, so I tell him the truth: a hundred.”

I blink a few times more.

“Nice guy. I bet he would shoot this. I wonder what I did with his phone number . . . ”

He trails off, rummaging through a stack of papers. After a moment, I realize he is actually looking for the number.

Pranka laughs, disappearing into the back of the shop. I return to the parts washer where I had been working, resume scrubbing the grime off an old Duetto block. James does the wuff-wuff thing, head back on the floor.

Again, I get paid. Not much, but then, neither is my labor.

It doesn’t matter. If he asked, I’d show up for free.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Thanks Sam Smith. I wish I could write like you did in college. I just never had the balls…or, the talent. Keep up the good work…for all of us.

“And yet, the lovers, they look away.” Or to the possibilities of a future, the Berlina waiting patiently (dreaming of rust?) like a loyal dog. The family unit. So very nice, this. Una cosa adorabile.

Just curious…. SLU or Wash-U?

I actually met you in Carter’s shop, Pranka’s an old friend. Love the work you do

“Hamlet in a helmet” What a great line to describe Phil in four words. Denise, a great writer and lady. Sam, as I’ve mentioned before – your words and love of the past make me want to see more! I’m blessed to have met all my hero’s from that golden age of racing and never tire of reading about them.