Avoidable Contact #119: Making the case AGAINST spec racing … using two Neons?

Question: How is this column like the recorded catalogue of the Beatles?

Answer: Beyond the obvious hits, there’s far too much drama, self-destructive behavior, indulgence of cutesy ideas, and narcissism masquerading as enlightenment. Also, not everything happens in the order you’d expect.

For example. Virtually all of Let It Be was already in the can when the Fab Four started recording Abbey Road. Due to various contractual and external circumstances, however, the latter album was released first, creating the impression that the band had terminated its existence with a fairly lightweight and slapdash soundtrack rather than with a finely tuned and perfectly judged swan song.

The same kind of thing is happening here at Hagerty Media. Last week, I told you about my frustrating Spec Racer Ford session at Waterford Hills just days after the event in question. Prior to that, however, I’d been working on the story you’re about to read, which is based on an SCCA race at Nelson Ledges that took place in July.

Why tell you all of this? Largely to prevent the impression that I immediately went racing with a broken wrist. That would be irresponsible, and I plan to wait weeks, er, at least one week, before doing that. Alright. Let’s continue with our story.

If you’re a modern club racer, you live in a world that is defined by “spec series.” The biggest classes in SCCA? Why, Spec Miata and Spec Racer Ford. (Pour one out for the Formula Enterprises and Enterprise Sports Racer projects, wonderful and lovely cars that never got the love they deserved from the buyers.) Over in NASA, we have everything from “Spec Iron” to the NP01 demi-psuedo-protoypes, with a half-dozen spec classes in between.

The arguments for spec racing are well-known and largely factual. If you join a spec series, you don’t run the risk of buying the “wrong car” for your preferred class; as an example of that, imagine being an NC Miata driver in NASA ST5 running against the Honda S2000s that seem purpose-built to loophole the NASA “average dyno HP” rules, or maybe being a Mustang V-6 driver in SCCA T4 after the NC Miatas and Civics arrived.

While running up front in a spec series can require an astounding amount of additional effort and attention to detail, you can usually enjoy yourself in the middle of the pack just by following the series recommendations. You’ll be surrounded by people who have spare parts for your car. Possibly you’ll even have series-specific vendors; try getting a Miata water pump at an SCCA regional, then try getting a water pump for an ex-World-Challenge Honda Accord V-6 at that same race, and you’ll quickly see why people like to race in packs.

There’s another reason frequently given for spec racing with which I completely disagree: it is supposed to provide higher-quality competition. How could it not? After all, you’re surrounded by cars that are just like yours! Of course the racing is going to be great!

And yet it so frequently is not. In the small-bore classes, bump drafting and partner-picking rule the roost as they do in NASCAR, while in the big-bore groups it can be extremely difficult to pass someone who gets to the corner just as quickly as you do and who has all the same tools at their disposal. Races are frequently won and lost based on minor setup changes or tricks that have yet to be widely understood. Allegations of cheating are commonplace, particularly in Spec Miata. Everyone is on the perpetual lookout for a car that seems to have a few extra horsepower.

The net result of all this? Follow-the-leader racing with a lot of crashes as desperate drivers make low-percentage moves on essentially identical competitors. Is there a better way? Maybe there is, and the aforementioned Nelson Ledges race gave me a brief glimpse of what it is.

I’ll start by introducing Sean Grogan. He’s an old Midwest hand in both autocross and roadracing, a respected shoe who has been running Neons in SCCA for quite some time. He was registered in the ITA class for the Ledges race. His Neon adhered to ITA regulations, which means: 2345-pound competition weight, 225-width Hoosier R7 tires, stock-ish two-liter SOHC engine built with care and love by Grogan and his crew.

The Neon that I brought to the race was very different; originally built to be competitive in NASA Performance Touring, it’s now an odd duck in SCCA’s STU class. On the day of the race I was using a 2600-pound minimum weight, an ex-minivan 2.4-liter DOHC engine with no additions or substitutions, and 205-width Hoosier SM7 tires, about which more later.

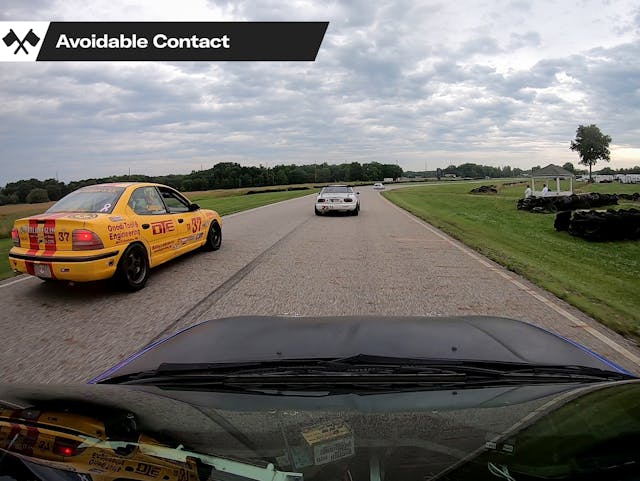

If you’re an experienced racer, you can already tell what kind of race we ended up having. I’ve included Grogan’s full in-car camera footage here, which runs from the moment he left his paddock stall to the end of the race. There’s no need to watch through it, but it might be a useful reference for what I discuss below.

At the start of the race, I used the superior torque of the 2.4-liter to close the qualifying gap between me and Grogan. I then passed him on the motor through the inside of the Kink at Nelson Ledges; this is the sort of so-bold-it’s-stupid first-lap move against which very few drivers think to defend. At that point, I had all the advantage I needed to win the race. My engine was worth perhaps one car length on the front straight and two on the back, and I was in front. Easy as pie, right?

Except.

Grogan’s lighter, grippier Neon was hassling me at every turn, like a PT boat confounding a destroyer in the Pacific Ocean. He simply had far more ability to place his car where he wanted it on the track. In the final turn, for example, I barely had enough grip to get around and on to the front straight, and I kept running wide as I attempted to conserve a bit of momentum through the 90-degree left and 180-degree right. Grogan suffered no such difficulty. He’s on the power and straightened out while I’m still trying to get at least one of my front tires to find some grip.

Knowing that his sticky Hoosiers would shed heat in a hurry, Grogan could repeatedly make threatening moves left and right going into a corner before coming out at the desired temperature. By contrast, every defensive shift I made further decreased my ability to get traction at corner exit, thanks to overheated rubber.

By the fourth lap, both Grogan and I had adopted our strategies. I would cover the inside of every corner exit, over-brake to slow Grogan down behind me and rob his midcorner speed advantage, then drive out on relatively cool tires with my superior power, pulling a car’s length or two on him before surrendering that advantage into the next turn.

Grogan, by contrast, pressed the attack over and over again, knowing that a single mistake on my part would allow him to make the pass. He’d be in danger of losing the position for maybe the next two straights, but eventually his superior cornering speed and overall better pace would win the day.

In a Spec Miata or Spec Racer Ford class, we’d have been dueling with equal vehicles, but here we were fighting the battle with cars that offered significant advantages and disadvantages compared to the competition. This meant that every single corner was up for grabs, over and over again, as opposed to a spec race where you’d bide your time, cool your tires, and attempt a single make-or-break pass after three or five laps.

Oh … and then it started raining. Which brought a hobbyist driver struggling on wet pavement in a tuned Miata back to us. With just a few minutes left, Grogan and I had to each make a guess as to what this slightly wobbly fellow would do.

I guessed wrong, and that’s how Sean won the race. Technically, we were both class winners, finishing at the sharp end of the field, but we didn’t care about that. This was a Battle Of The Neons and the devil take the hindmost.

That was me. I was the hindmost.

So why this sense of joy after the race? Why did Grogan and I end up chatting in animated fashion for almost an hour afterwards? I think it was because we’d just experienced the kind of competition of which we all dream when we start racing. A hard-fought and clean battle between two evenly, but not perfectly, matched car/driver combinations. It gave us each a chance to demonstrate some race craft, run at the limit, and try more close-coupled pass attempts in a single race than some people see in a season.

The experienced SCCA racer will see that neither Sean nor I were fielding a Runoffs-spec car, and we were occasionally either sloppy or overenthusiastic in our moves. It didn’t matter. We had the kind of fun that restores one’s faith in the very idea of club racing.

Could it be possible for more people to have this kind of fun every weekend? Sadly, it’s not really up to the racers. It’s up to the people who write the rulebooks. What if you could pick and choose your race trim within a particular class? Give up some tire for some power, or vice versa? In NASA Super Touring, you can do exactly that—but the effects of those changes are not widely understood, and most people make the semi-sensible decision just to copy a car that’s already winning in their region.

What we need is an accurate and repeatable data model that predicts the difference between various race configurations. This super-computer would look at my Neon and Grogan’s Neon, then accurately predict my supremacy in Lap One, as well as my struggles afterwards. It could adjust a Sentra SE-R to run competitively with us … or it could adjust a C4 Corvette to run competitively with us, maybe.

This computer would look at race results across the country every weekend, absorb the lap times, and make appropriate adjustments in what you’re allowed to have for the next season. Maybe we could also enlist the help of the online racers, who do a lot more laps than we do and who can change tires and engines with zero real-world cost.

There would be a few other benefits from such a system. The number of classes could be reduced as the computer matched cars with similar potential. Consider, if you will, the years when both Spec Neon and Spec Focus raced in NASA. They were probably a single tire choice away from turning almost identical lap times, and the field could have been doubled as a result. Bigger fields means more fun and closer racing for everyone.

While the core idea of performance balancing isn’t new, the idea of using a cloud computing resource to immediately absorb all of the club-racing data out there probably is. We’d need to add a few extra steps to the registration process for most races; you’d put in your tire information, engine information, and maybe a little bit about your aero or other performance mods. The data wouldn’t have to be all that comprehensive in order to yield at least some results.

I know this will seem ridiculous to most of my racing-licensed readers. They’ll point out that I could get some great racing by returning my Neon to ITA spec and running in ITA, and they’re right. In response, I’d challenge all of you to think of the greatest race you ever saw. Was it between identical cars? And if it wasn’t, what effect did the differences between the cars have on the racing?

Give it some thought. As for me and Grogan, I think we’ll have a chance to reignite this rivalry in the season to come. I’ll bring better tires (the SM7s were all I could get on short notice, sadly) and he’ll no doubt have a few improvements to his Neon as well. It’s impossible to know who will triumph, but what I do know is that we’ll each be glad to see the other Neon show up. And, in the end, isn’t that really what club racing is all about? Isn’t the competition you make … equal to the competition you take?