The history of the Pikes Peak Hill Climb: A challenge for man and machine

As you drive west through the Great Plains Heartland of America, across the flatlands of Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and Kansas, you’re greeted by the towering granite of the Rocky Mountains, whose peaks rise, in various areas, to more than 14,000 feet. If you’re a fan of cars, you are probably familiar with one snow-capped location in Colorado, on the eastern edge of the mountain range—Pikes Peak. Though 27 mountains rise higher than Pikes Peak—at 14,110 feet, it is less than half the altitude of Mt. Everest—this Colorado peak is the one that has character.

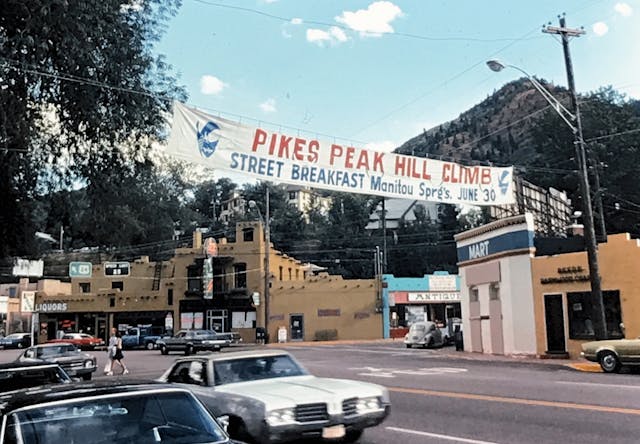

Native Americans once built a small settlement into the cliffs at the base of this mountain and named it Manitou (the Indian word for Supreme Being or God). Known today as Manitou Springs, the town is due west of Colorado Springs and is referred to as the keeper of the mountain. During the Gold Rush days of the 1800s, settlers were drawn to this intimidating natural wonder, which inspired Katherine Lee Bates to write “America the Beautiful.”

In 1806, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, a U.S. Army officer, was commissioned to lead an expedition west across the Great Plains and into the purchased Louisiana Territory. Pike, who is credited with discovering the mountain, remarked that it would be impossible to ascend to the summit because of snow and subzero weather during the winter season. Of course, 14 years later, a cog railway—and, later, a motor road—was built, bringing thousands of tourists to the top of Pikes Peak every year.

In 1916, the first “Race to the Clouds” was organized as a stunt to publicize the opening of a toll road. Privately owned by Spencer Penrose, and groomed with crushed granite gravel, the road started at 9402 feet above sea level (Crystal Creek) and ran 12.42 miles to the summit. To this day, there are 156 curves, some with sheer drop-offs from 800 feet with no guardrails.

The challenge up the Hill is the second-oldest regularly scheduled race in the U.S.—only the Indy 500 is older. The Pikes Peak Hill Climb has been run every year since 1916, with only a handful of exceptions: 1917, 1919, 1935, and 1942–45. All were war years except for ’35, when Penrose withdrew from the toll road and the race was canceled. The following year, a group of American Legionnaires pitched in to keep the race alive.

The original sanctioning body was the American Automobile Association but, in 1956, the United States Auto Club took charge and scheduled the race for Labor Day.

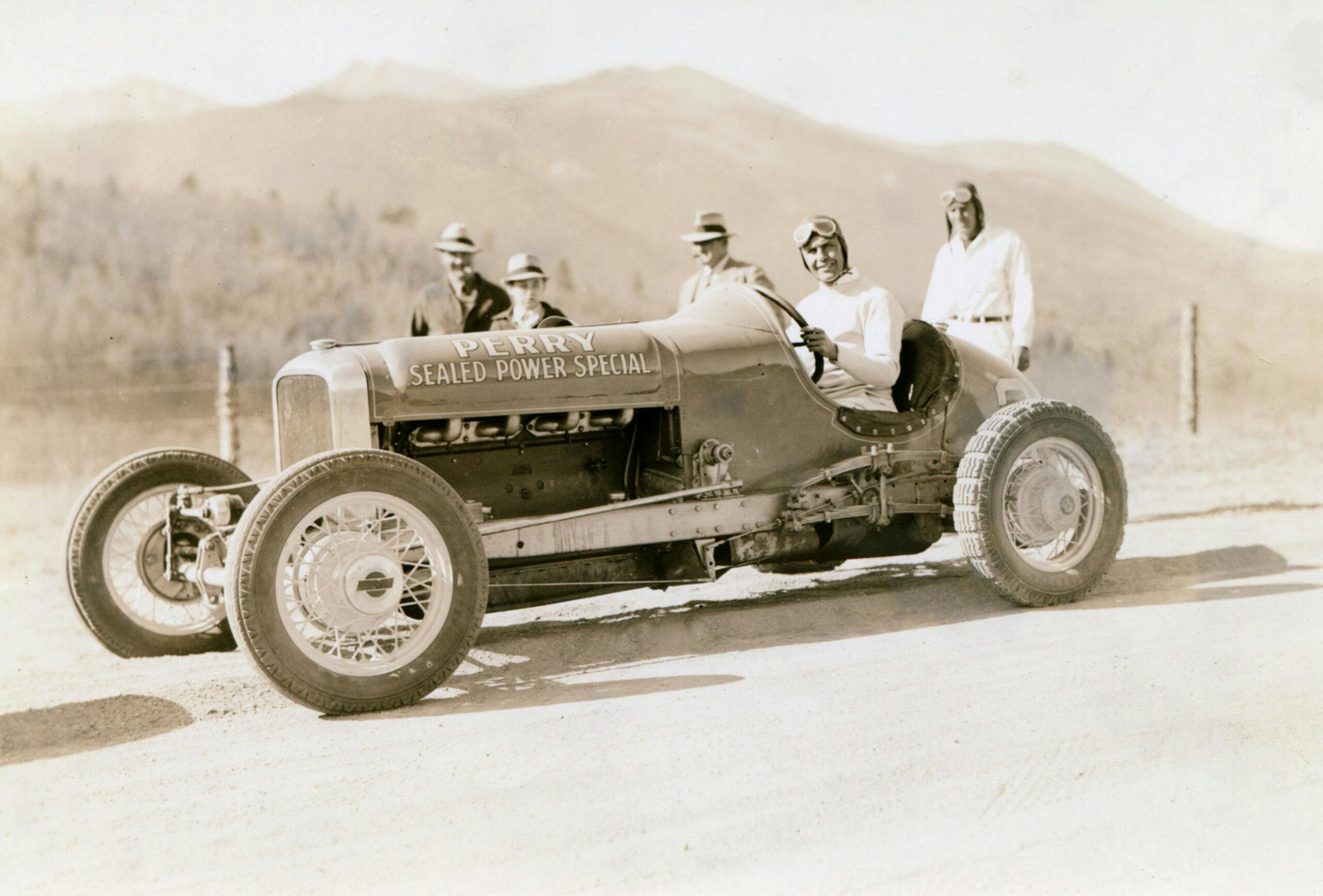

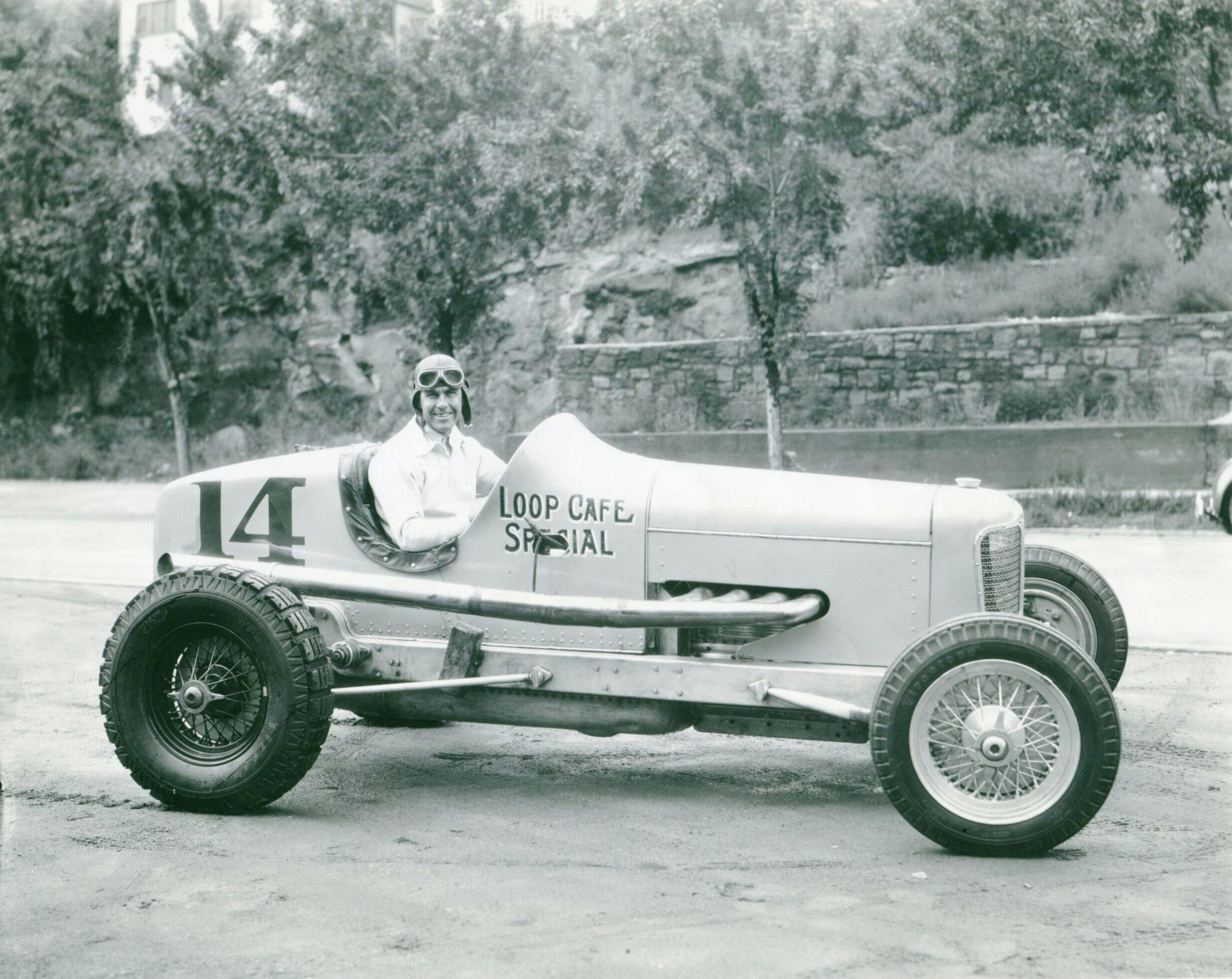

As early as that first race in 1916 (won by Ralph Mulford driving a Hudson Super-Six Special to the summit in 18:24.7), the “Unser Dynasty,” who had immigrated from Switzerland, made an appearance with three young motorcycle racers: Louie, Jerry (short for Jerome), and Joe. They actually rode their bikes to the summit while the road was still under construction, but it wasn’t until 1926 that now-famous racers entered the hill climb. Not for another 10 years would an Unser set a record at the mountain: In 1936, when Louie ran a Stutz Special up the Hill setting a record time of 16:01.80. He did it again in 1938, driving a Loop Café Special to a record time of 15:49.90.

The 1950s brought changes such as the introduction of sports cars. Motorcycles were reintroduced in 1954. The original sanctioning body was the American Automobile Association but, in 1956, the United States Auto Club (USAC) took charge. The stock-car division that had ended in 1934 also returned for 1956, when the race date changed from Labor Day to the Fourth of July.

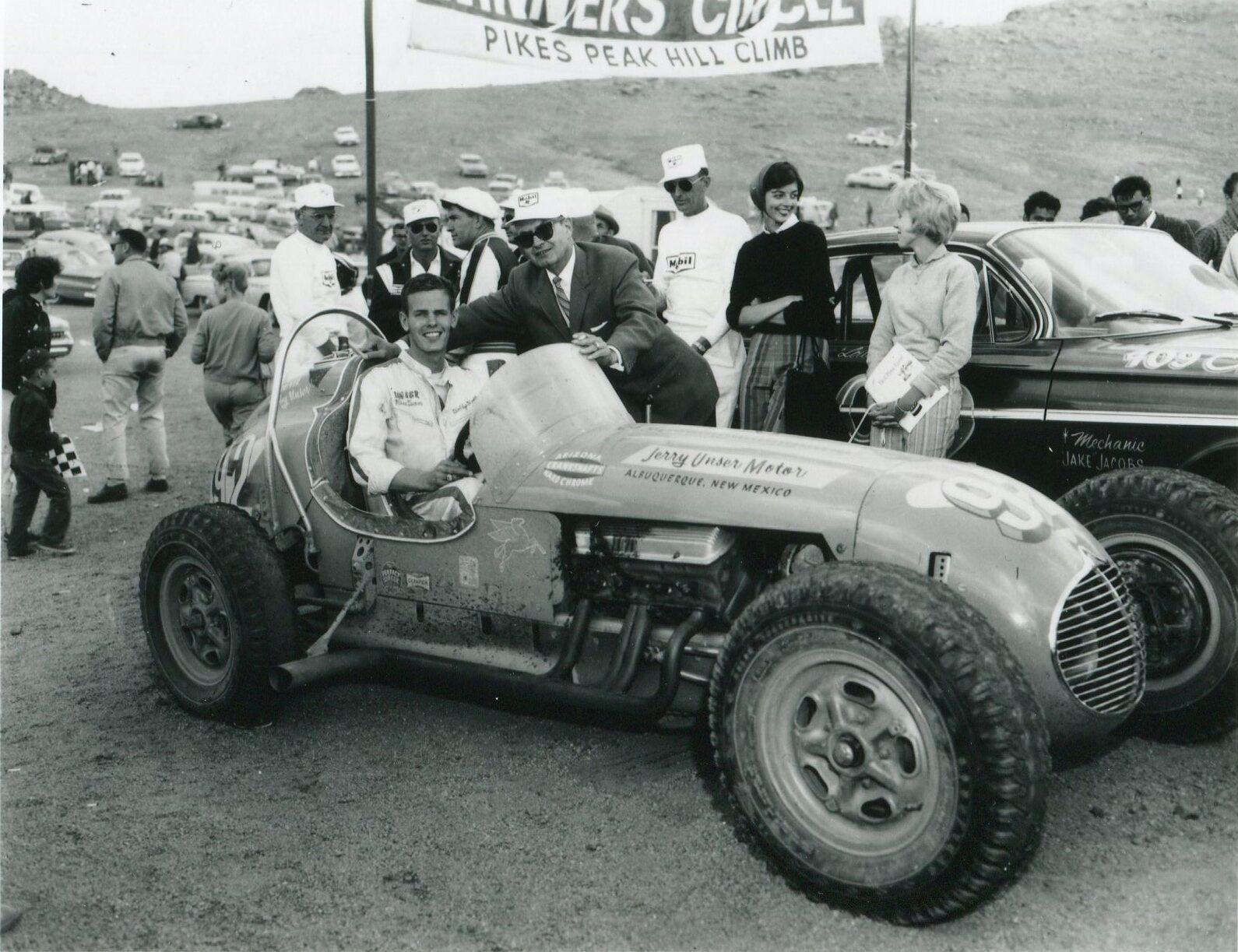

The most important occurrence during the 1950s, however, was the “invasion of the Hill” by the Albuquerque Unsers. In 1955, four Unsers made a grand statement: Uncle Louie and three boys—Bobby (21 years old), and 22-year-old twins, Jerry Jr. and Louis Jr. One of the twins, Jerry, drove a blown ’57 Ford and took a win. The brothers even got Hot Rod Magazine as a sponsor.

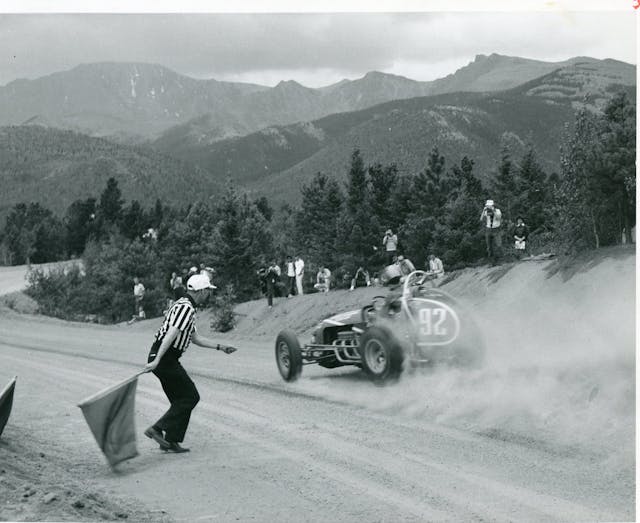

By the ’60s and ’70s other names had become prominent at the Hill, like Curtis Turner, Parnelli Jones, Mario Andretti, Roger Ward, Roger and Rick Mears, David Pearson, Bud Tinglestad, and others. In 1963, American motorsports promoter J.C. Agajanian came on the scene as managing director and immediately increased the purse to $22,000. In 1971, VW- and Corvair-powered buggies entered, and made a splash: Roger Mears took the win in a VW-powered buggy while he and his brother Rick won two more times. V-8-powered buggies started to dominate by 1979 when Richard Dodge, in a Well Coyote V-8, broke Bobby Unser’s record set in 1968.

In the ’70s, I had been active in motorsports photography as West Coast photographer for Valvoline Oil Company. I covered everything: NASCAR, Formula 1, Indy at Ontario Motor Speedway, the first Long Beach Grand Prix (Formula 5000), and drag racing at all the drag strips in Southern California. In 1974, I was approached by Road and Track magazine to cover the Pikes Peak Hill Climb and immediately started doing research on the “Race to the Clouds” on what had been nicknamed “Unser Mountain.”

I packed up my Dodge van with all the appropriate gear and sleeping bags (I slept in the van) and set sail on a 1087-mile trek to Colorado Springs for the 58th running of the Pikes Peak Hill Climb. I planned on camping in my van near Devil’s Playground, where thousands of spectators were camped in tents and sleeping bags. I have been a Bobby Unser fan for years, so I was excited to find out that, after a five-year absence from competition on the Hill, Unser was returning to drive Dodge’s new “Dart Kit Car” racer in its debut appearance.

Unser once said, “I feel that I owe a tremendous amount to the people I’ve met up here over the years. I also think it’s probably the greatest race in the world. I would rather run Indy because it pays a helluva lot more money, but for fun, I’d rather run Pikes Peak.” Fact is, Bobby Unser was dead serious about remaining “King of the Hill,” but 27-year-old Roger Mears was set on replacing Unser.

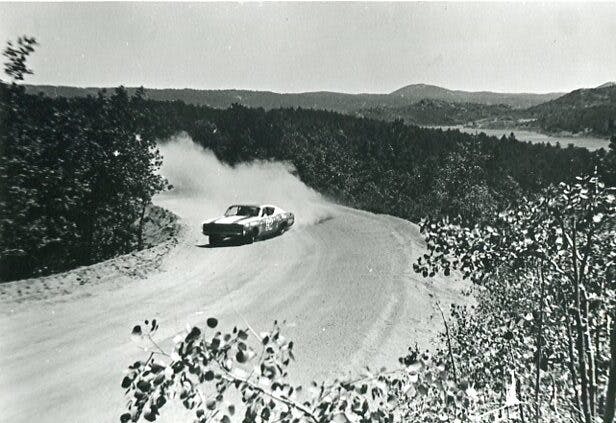

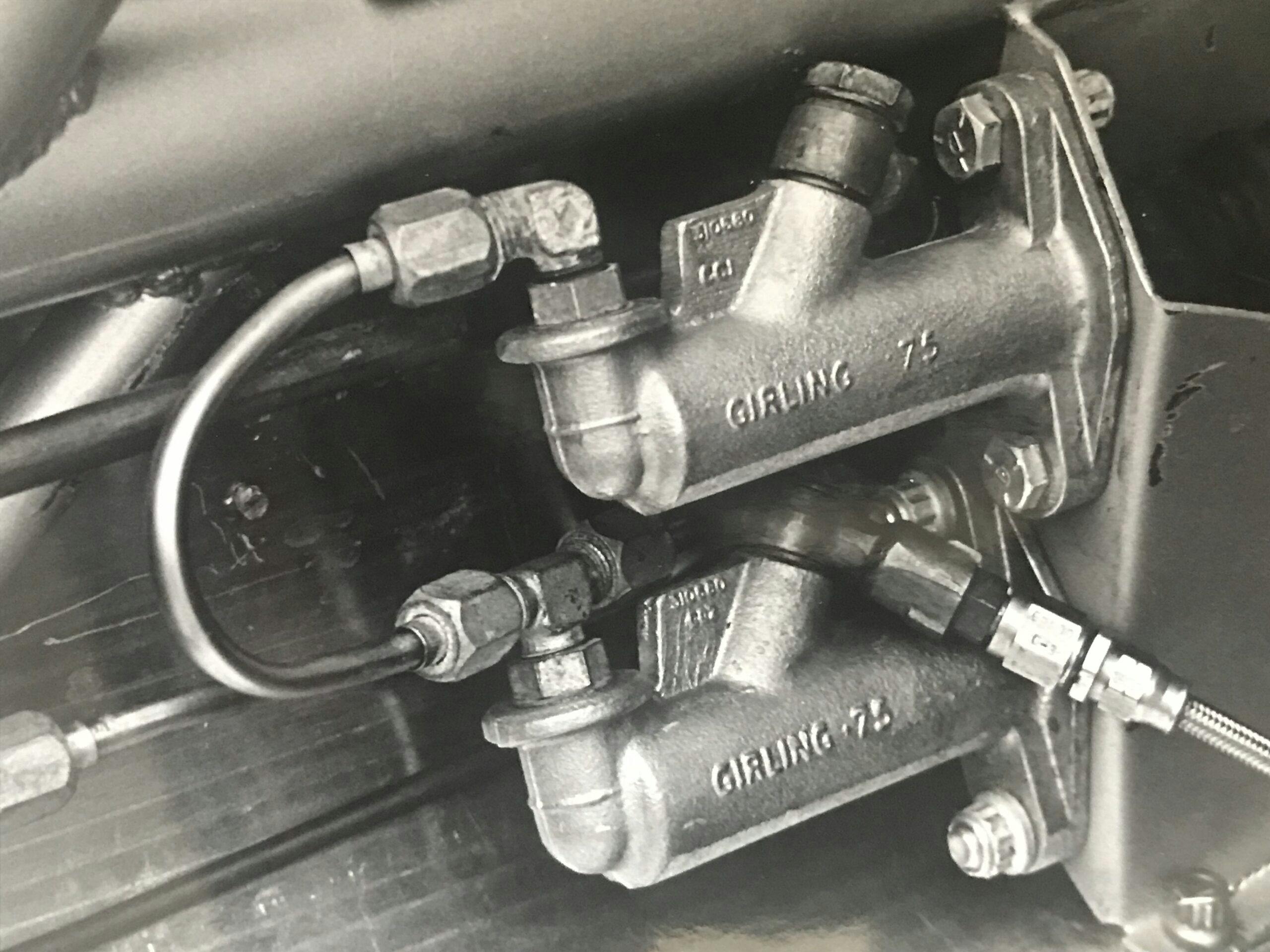

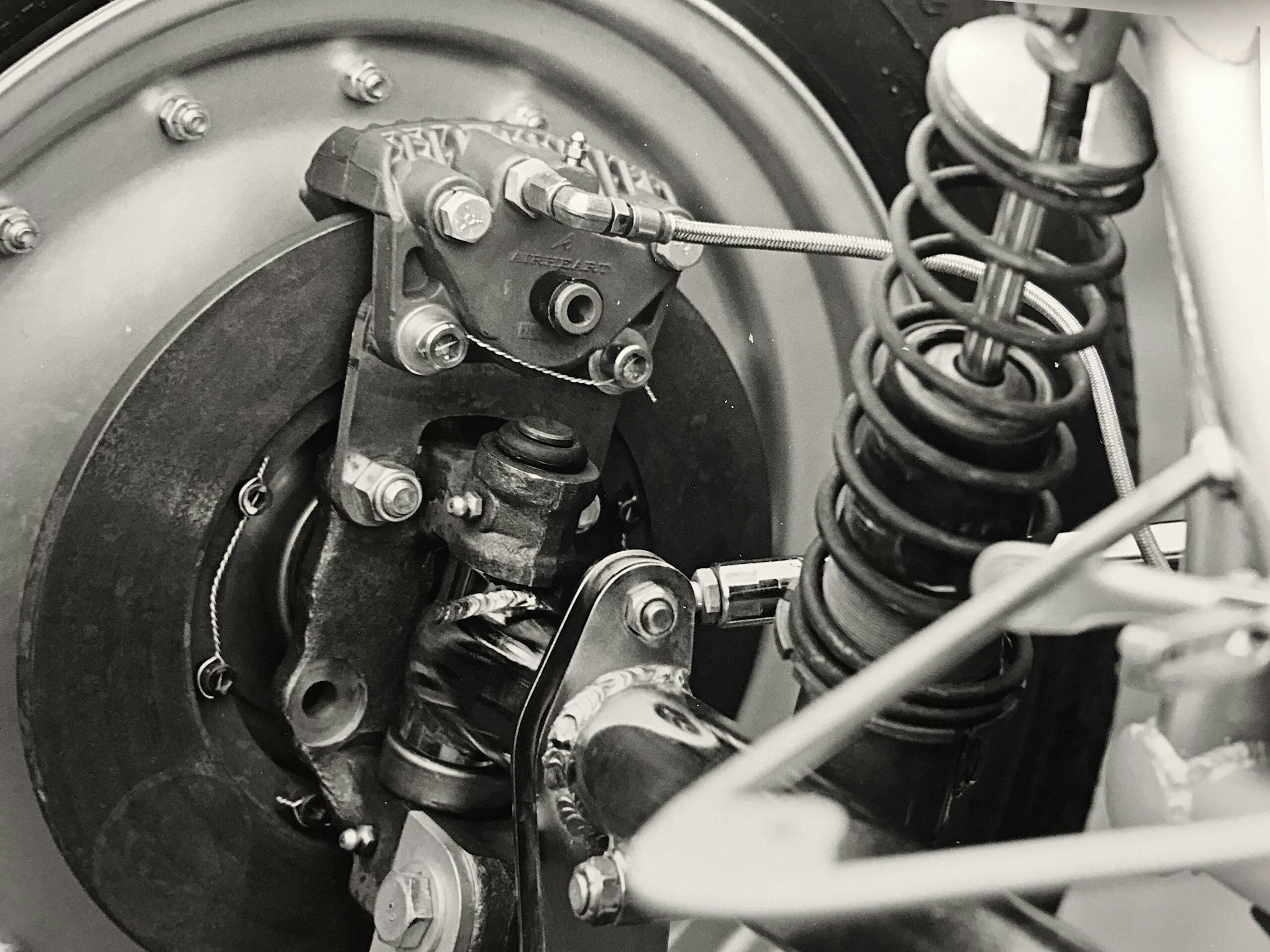

Mears had the machine to do it, too: a VW-powered dune buggy equipped with two braking systems, one to pinch all four rotors, and another that allows the driver to brake each rear wheel independently by pulling a handle that is hooked up to two more master cylinders located in the cockpit. The fiberglass body of the buggy was handmade, with the center section molded from a Lola T300 Formula 5000 car. Mears then fabricated his own front and rear sections to produce the three-piece body. His work paid off: Mears took the win in Open Road Class in 1972 and 1973, placed third in 1974, and finally won overall in 1976 driving a Newman-Dreager Porsche @ 12:11.88.

Bobby Unser Jr., joined the Hill Climb brigade in 1976, 1977, and 1978 driving an open-wheel Chevy 327 and managed to place second in a Chevy 350 in 1977 with a time of 12:16.90. In 1981, ’82, and ’83 he piloted an ’82 Wells Coyote and placed a few times.

In the 1980s, pro racing cars made the scene including Audi, Peugeot, Subaru, Suzuki, Mazda, Porsche, Lancia, VW, and Toyota, each manufacturer ready to make its bid to the “Race to the Clouds.” Audi became a serious competitor at this time building versions of the Quattro rally car. History was made in 1985 when a French woman, Michèle Mouton, broke the overall record with a time of 11 minutes, 25.39 seconds. In 1994, Rod Millen chopped 40 seconds off that record in his Toyota Celica.

One name resonates when you refer to the Pikes Peak Hill Climb: Jeff Zwart, noted still photographer, film-maker, Porsche collector, co-founder of Racer Magazine in 1992, and graduate of Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. Zwart entered the Hill Climb in 1989 in production division driving a Mazda and in 1994 he drove a 1990 Porsche and nabbed first place. For many years Zwart has challenged the Hill and has claimed multiple division wins on America’s Mountain. “Pikes Peak is a living organism,” he said. “There’s never a year that has been alike. I favor the dirt road. Just much more fun to drive on a road that makes a car move under you.” He was inducted into the Pikes Peak Hill Climb Hall of Fame in 2018.

At the 2023 Hill Climb, Zwart drove a 2019 Porsche 935/19 to a ninth-place finish (9:46.131), but Robin Shute drove his 2018 Wolf TSC-FS to the top in 8:40.080 and grabbed the win.

Pikes Peak champion Rod Millen once said, “Paving the road would be dangerous. It’d be like running the Long Beach Grand Prix with no barriers between the track and the spectators.” However, as of 2011, the road is paved and thus grippier. (The Sierra Club spurred the change when it claimed that using dirt as the race surface was causing serious environmental damage.) The cars have become lower and faster, and their aerodynamics have changed. They race on slicks rather than treaded tires. The overall record is held by Romain Dumas, who piloted his all-electric VW ID.R to a time of 7.57.148 in 2018.

The 102th running of the Race to the Clouds—officially known as the Broadmoor International Pikes Peak Hill Climb, presented by Gran Turismo—is scheduled for June 23, 2024. You can find more info at www.ppihc.org.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I still remember my drive up Pike’s peak. It was an enjoyable drive and the scenery at the top is amazing.

I lost interest in this when they banned motorcycles. Paving all the way to the top didn’t help either.

Too many riders were killed.

Kind of a no-brainer.

Labour day would make more sense as all the snow would be gone by then.

Oh, no. By then you’re due for *next year’s* snow. I have been stopped and turned back at the Glen Cove Inn, halfway up, on July 31 because there were snow squalls from there to the summit. They let me back the next day, and it was summery and beautiful all the way. There is no time when there is no snow there.

Incorrect, but yes, snow is sometimes is a problem.

Yes, it’s just in the shaded areas by then.

Check out this year’s videos.

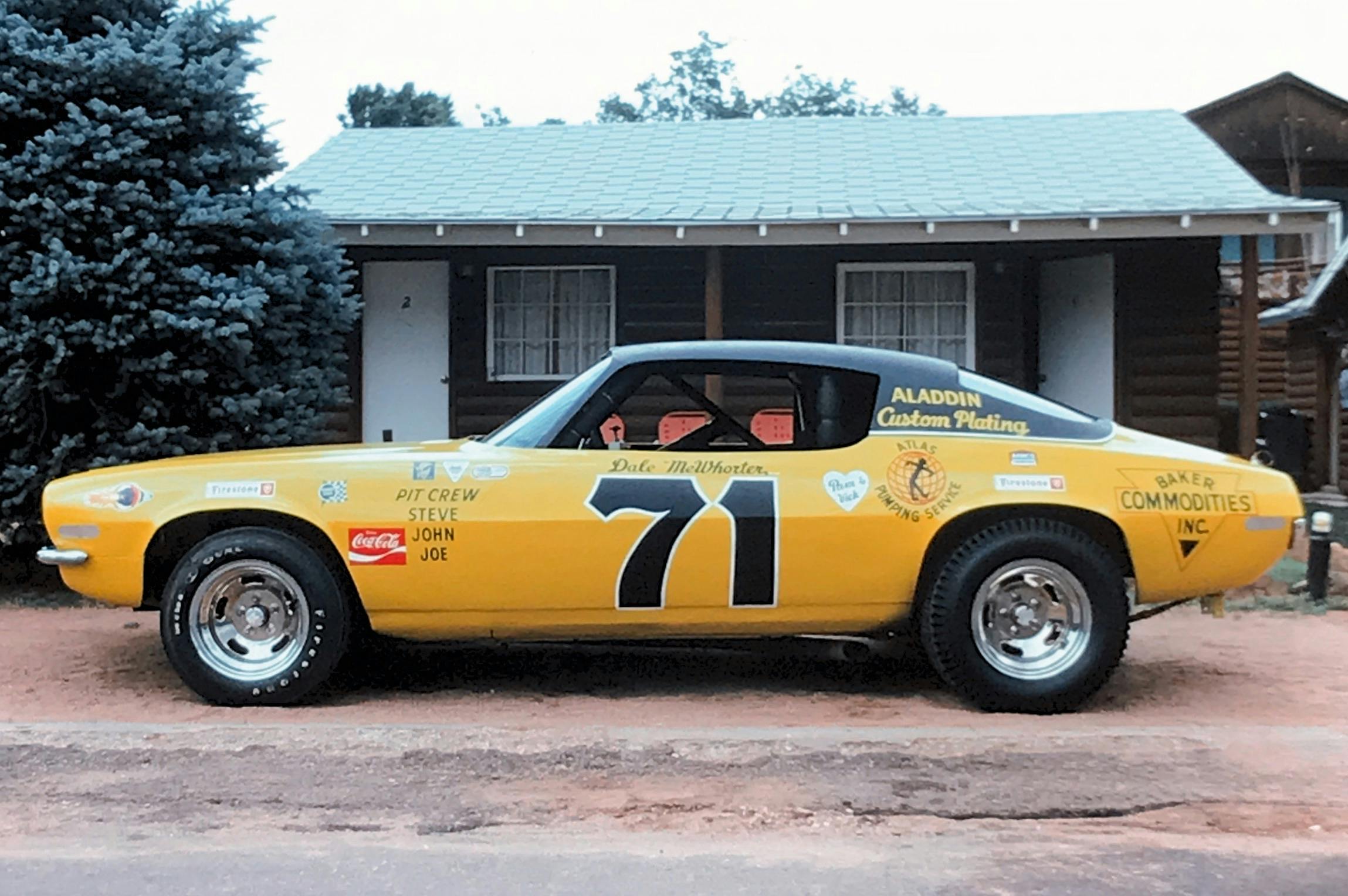

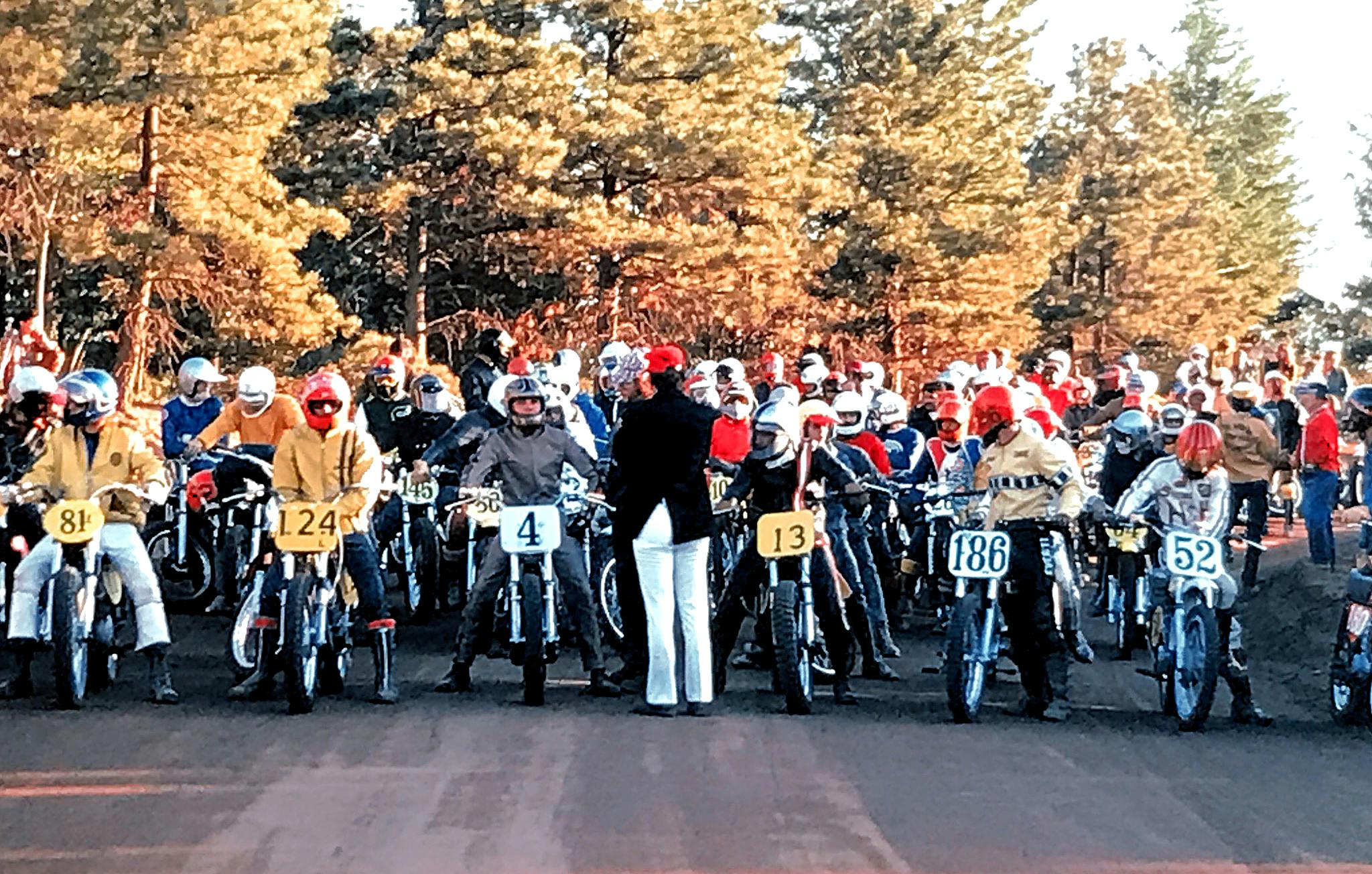

Cool pictures but who’s idea was it to have pictures without captions? Who’s car? Who is the driver. Who took the pictures is secondary after you describe what’s in the picture.

My first thoughts at each picture were: Who’s the driver? and what’s the car? How annoying!

The major races of the world are run on courses that are alive. LeMans and Indy are very large tracks and change accordingly. Pike’s Peak is a freakin’ mountain and you have to have huge cahones to try to conquer it. Some say you have to be nuts to try. Others say you have to be fast. It ought to be televised! The folly of competition at it’s finest.

How you can write a “brief history” of Pikes Peak without mentioning Ari Vatanen,or Rauno Aaltanen beggars belief.

@ Peter Edwards : I agree, it is amazing to not mention Ari Vatanen and his famous “Climb Dance” :

https://youtu.be/UEuZG37gFdM?feature=shared

This is really cool! I never knew these facts!

Make more like this please! oh and can you please disable the thing that says your posting to quickly being fast is kinda my thing (just like sonic LOL)