Midget racing invades Indianapolis Motor Speedway

For a testament to the popularity of circle-track dirt racing in the United States, look no further than the clay oval carved into the infield of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. While attendance has dipped among some of the country’s national racing series, both spectator count and purse values are trending up in the dirt-racing world. Despite the cost of diesel, car count remains steady. The scene is so hot—and critical for the future health of premier divisions—that even America’s most popular venue, a squeaky clean mecca of speed, is getting in on the mud-caked action.

First constructed in 2018, the track was a joint venture between the United States Auto Club (USAC) and the IMS. The banked quarter-mile was erected just inside the apex of the 2.5-mile speedway’s third turn, with permanent barriers installed around the perimeter and temporary grandstands lining the front stretch. A ceremonial yard of bricks was mortared into the wall below the starter’s stand. The event was christened “The BC39” after Bryan Clauson, an accomplished dirt racer who made three Indianapolis 500 starts before he was slain in midget competition.

Over 100 drivers showed up to that first race.

The race quickly became a crown-jewel event for dirt racers. Every summer, contestants flock from numerous states, multiple countries, and several disciplines to try to tame the bull ring aboard their four-cylinder powered open-wheelers. Now in its fourth year, the midget race held in the shadows of Indy’s iconic pagoda is bigger than ever.

For 40 years, USAC was the sanctioning body for the Indianapolis 500. Then, in 1996, it was booted from the race following the advent of Tony George’s Indy Racing League. Still, the club continued to call Indy home—literally occupying an office outside of the Speedway’s first turn—as did nationally sanctioned road racing, karting, and other open-wheel disciplines, including dirt midgets.

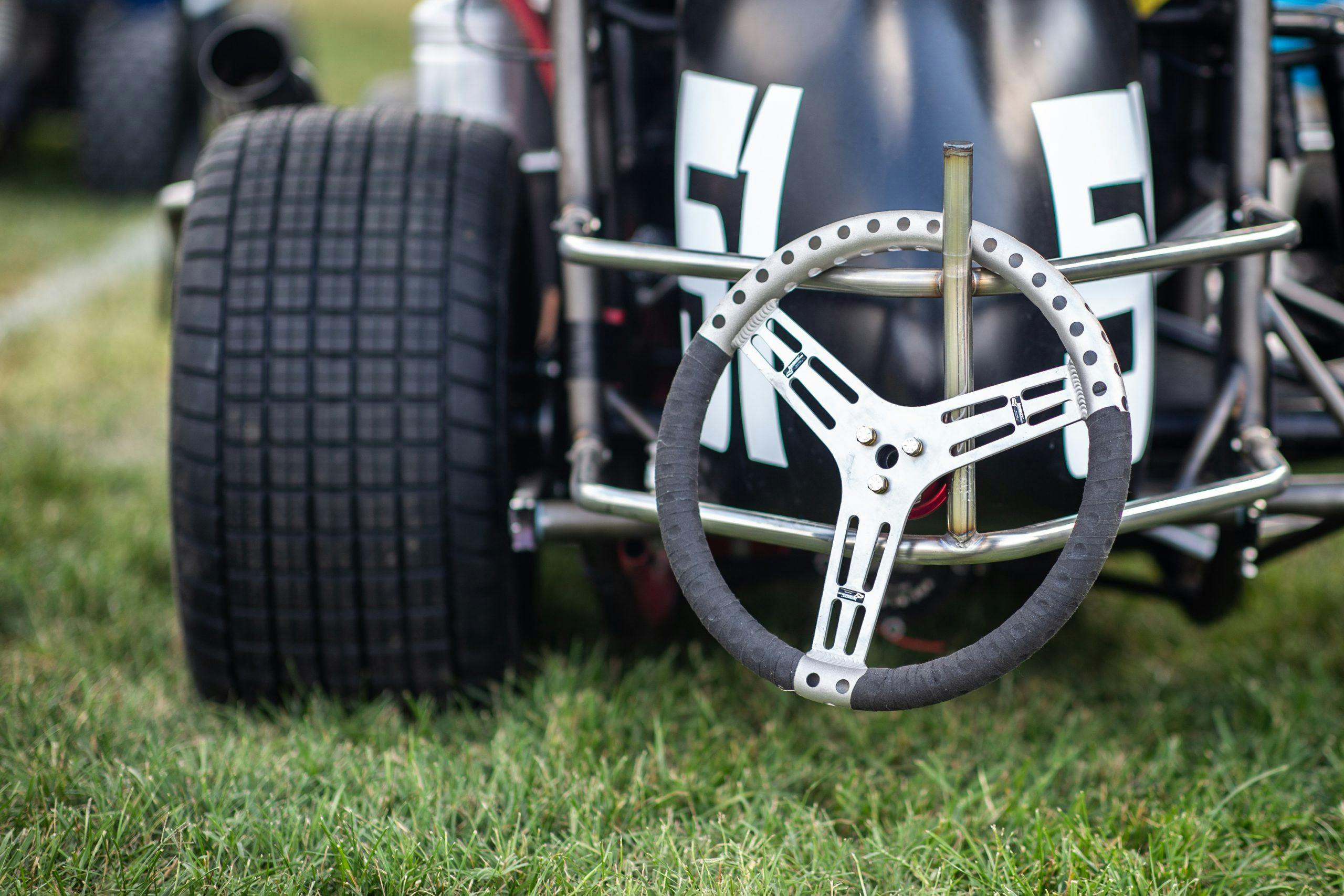

USAC’s national midget series is a hot bed for young talent. The tube-frame cars weigh less than 1000 pounds, have 400 horsepower, solid axles, and no traction control—a recipe for burgeoning drivers to sharpen their control. NASCAR stars like Kyle Larson and Christopher Bell first cut their teeth in these pint-sized buggies on the bull rings across the country. Prior to them, Tony Stewart, Jeff Gordon, and A.J. Foyt each found victory in midgets early in their hall-of-fame career. This year’s roster featured a few current NASCAR drivers, IndyCar veteran Zach Veach, and ten-time sprint car champ Donny Schatz. The diverse field also featured seven female racers.

Midget racing’s most prestigious race, ironically not sanctioned by USAC, is the Chili Bowl in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Last winter, editor-in-chief Larry Webster made his dirt debut at the annual indoor contest, slicing and dicing with nearly 400 other entrants. If the Chili Bowl is the Daytona 500 of midget racing, consider the burgeoning Brickyard battle a close second.

“Next to Chili Bowl, this is the hardest race to make,” says NASCAR Cup Series regular Chase Briscoe. “You’ve got 80-something drivers here. I feel like it just keeps getting bigger and bigger every year.” Briscoe, an Indiana native who race midgets long before he strapped into stock cars, affirms that the venue definitely plays into the prestige.

“Any time you can race here—whether it’s the oval, the road course, the dirt track, the parking lot—it’s just special. I think everybody in motorsports dreams of getting to race at Indianapolis.”

In addition to enticing unique drivers into the fray (ones who might not make more than a couple midget races all year), a unique subset of fans were also in attendance. Some declared that the dirt track at IMS was their only experience with short-track racing. It’s a reminder that some fans follow the track itself and support the venue regardless of the racing that takes place on the grounds. New followers are good for both parties, USAC and IMS.

Those in attendance are treated to an epic, two-night schedule of racing, sliding, and tumbling. As the night matures, the surface evolves. Loose dirt packs against the wall, forming a “cushion.” Only the most precise—and often the fastest—drivers place their right rear against the embankment which guides the car around the corner. Climb too far up the clay curb, and calamity ensues.

Each year, the venue produces some of the season’s best finishes. “The track was purpose-built for midgets, so that definitely helps,” says racer-turned-reporter Dillon Welch, who temporarily traded his NBC mic for a helmet and a shot at Indy glory. “The guys who prep the track are the best in the country, in my opinion.”

IMS employed Reece O’Connor of neighboring Kokomo Speedway to oversee the track layout and supervise the construction. Unlike a pavement course, surface work never ceases on a dirt track, so every year IMS brings O’Connor back to prep the circuit ahead of the show. Keeping the right level of moisture in the clay is the key to an exciting race, and it takes an experienced groomer like O’Connor to maintain a track, especially amid the unpredictable weather of August.

Competition was electric in 2022. 16-year-old Dominic Gorden held off a slew of veterans for the biggest win of his young career on the first night. During the second evening, IMS treated fans to a special exhibition run by Indy 500 winner Tony Kanaan. IndyCar veteran Kanaan suited up for several laps aboard a midget, a task that made the Brazilian superhero look human. “The sensation of speed is 10,000 times that of an IndyCar,” he said following his first laps in the car. Buddy Kofoid, a rising star destined for Sunday racing, took the feature win that night.

The dirt oval is part of a larger trend at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. For decades, the track lay dormant for most of the summer. NASCAR arrived in 1994. Formula 1 followed for a spell. Now, the track is consistently humming with the sounds of race cars—a second IndyCar date, NASCAR’s Xfinity Series, GT World Challenge, and the IMSA WeatherTech Series in 2023.

IMS President Doug Boles has been responsible for much of this growth, the dirt race included. Before this year’s contest, he told reporters that the BC39 is his second-favorite race of the year, runner-up to the Indy 500.

“It’s a way to connect to heartbeat of our sport,” Boles said in an interview with FloRacing. “Our sport doesn’t survive without the local racetrack and through the national level of drivers who support those tracks.” During the event, the hands-on boss Boles was true to form, holding court with drivers and shaking hands with seemingly everyone in attendance. After drivers retired from the race, it was often Boles who commended the driver for their valiant effort before any team member.

With support from Boles and the rest of the IMS crew, it’s no wonder that this burgeoning dirt race is experiencing such immense success. Paired with the celebrity status of the Speedway and the disciplines’ momentum, the dirt race in Indy’s third turn has a bright future.