Stock Stories: Moto Morini 3 1/2

With custom-bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of early two-wheeled machines are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles. -Ed.

Alfonso Morini founded his namesake motorcycle company, Moto Morini, in Bologna, Italy, in 1937. Bouncing back after WWII, production resumed and the company’s T125 two-stroke, based on the successful DKW engine design, was so successful that that many marques copied it—the most famous being the BSA Bantam. Throughout the next two decades, Moto Morini would fulfill Alfonso’s passion for motorsport and win hundreds of races.

However, it wasn’t until after Alfonso’s death in 1969 that one of his company’s most celebrated bikes came into existence: the Moto Morini 3 1/2.

The heroic Heron

Daughter Gabriella took over control of Moto Morini. In 1970 she hired 25-year old designer Franco Lambertini. Born in 1944, near Moderna, Franco Lambertini took on an apprenticeship at a young age as a mill operator and technical draftsman of mechanical gears, presses and tools. He next worked for Ferrari, where he bounced around various departments designing engines, gearboxes and car chassis. During this time he found that his passion was in design, and he considered himself an artisan.

At Moto Morini, Franco was tasked with drawing up designs for a Heron-type combustion chamber for the Corsaro Regolarita set to race in the 1971 International Six Days Trial (ISDT). It marked the first time a Heron-type chamber had been used in a series production motorcycle, and this design would ultimately become integral to the 3 1/2 story.

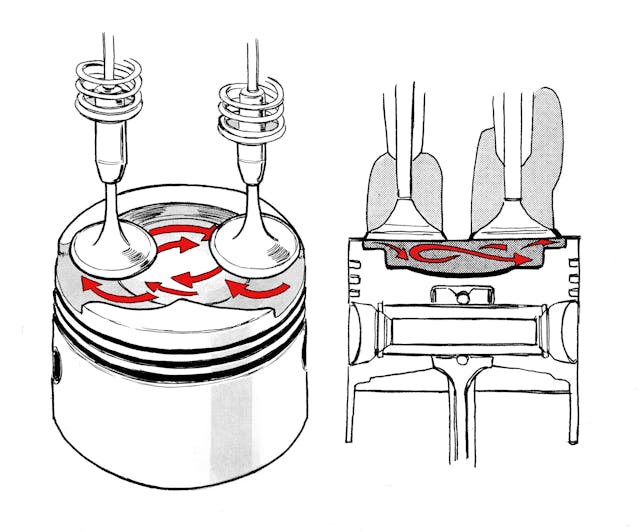

A Heron-style chamber incorporates the combustion chamber in the top of the piston rather than casting it within the head of the barrel. The design uses a main bowl at the center of the piston top, along with two half moon squish areas. These squish areas compress the inhaled mixture, forcing it across the chamber and creating a very turbulent mixture which in turn allows for excellent combustion and thermodynamic efficiency. Manufacturing Heron chambers is also efficient; the barrel head is simplified and the machining is all within the piston, which can down the road be easily refined and replaced without changing the manufacture of the cylinder head.

The Heron design had seen success in the Repco Brabham 3.0-liter V-8 engine that dominated the F1 scene from 1966-67, beating the Ferrari 3.0-liter V12. Franco must have been very aware of the efficiency of the Heron design having worked for Ferrari and would have most certainly taken note.

Morini entered 12 single-cylinder machines into the 1971 ISDT, with a mix of 125cc and 160cc machines. Out of the full contingent Morini achieved six Gold and two Silver medals. With the success of Franco’s design work on the single, he went on to work with Gianni Marchesini (general manager) on the company’s first v-twin engine. Also using the Heron-style chamber, this 350-cc, 72-degree engine would go on to become Morini’s most successful powerplant.

V-twin for the win

In the early ’70s the European market were lapping up 350cc motorcycles, the most popular being sporty singles. Franco nevertheless identified the v-twin for the basis of a flexible and adaptable engine that could power wide range of motorcycles. Its modularity would ensure a longevity to the initial design and make the investment in tooling, production, and parts support cost-effective.

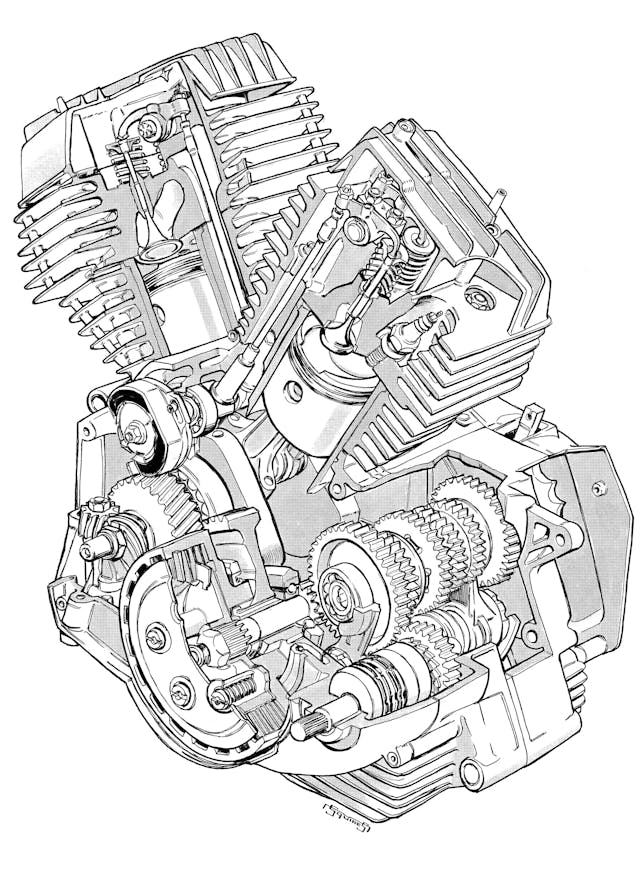

The chosen v-angle was 72 degrees, a value only really seen in aero radial engines at the time. This allowed for a shorter and more compact footprint, and the good balance factor also meant the front barrel was at a sensible cooling angle should they convert the design to a single. Franco also made the engine compact, with the layout including short pushrods with the cam centrally located and positioned as high as possible. The cams were originally driven by a toothed belt, but later variations of the engine would use gears for the timing—an innovative design.

The v-twin design incorporated a close-ratio six-speed gearbox. This transmission allowed the rider to be in the right gear at the right time to maximize engine performance.

V-twins, however, suffered the age-old problem the cooling of the rear barrel. While Harley Davidson used alloy to improve cooling, Franco employed a more cost-effective solution: 50mm offset for the barrels, so that the rear would receive sufficient cool air (rather than the majority of the air being warmed first by the front cylinder). In the 350 v-twin, the difference in temperature between the front and rear barrels was never more that 15 degrees.

With all these innovations Morini insisted that some traditions stayed, including a righthand gear change and kickstart that were nods to classic British off-road singles. Though technically antiquated at a time when other motorcycles would have offered electric start and left had change, the old-school aspects of the 350 had specific appeal, particularly to the large U.S. market.

The 3 1/2 emerges

The first incarnation of the Morini 350 twin used an over-square barrel of 62-mm bore and 57-mm stroke. This large bore size was intentional; it helped the Heron piston work efficiently when paired with appropriate valve sizes, with inlets at a large 30 mm and outlets at a relatively small 22.5 mm. This design allowed a positive scavenging effect and maintained the speed of the exhaust flow. The fuel mixture came courtesy of a pair of Dell’Orto VHBZ 25BS concentric bowl carburetors, which also worked well with the efficiency of the Heron piston. The twin used a noteworthy high compression of 10:1 in the standard engine and 11:1 in the Sport version, ratios which were high for an air-cooled engine of the time.

First shown at in 1971, the prototype motorcycle first wore “350” on the oil tank rather than the now-established “3 1/2.” Morini made sure that not just the engine and chassis were Italian, but that all the ancillary parts such as the clocks, Grimeca brakes, Borrani wheel rims, and Marzocchi shock absorbers were all domestically produced.

Moto Morini formally made the 350 available in late 1973 as the 3 1/2 Strada (touring) model, distinguished by its conventional handlebars and blue paintwork. The more famous Sports model was red with dropped handlebars and a steering damper for a more athletic feel. Both models were fitted with a solenoid which switched on the fuel tap with the ignition. The Strada used a twin leading shoe brake to go with the milder tuning of its engine.

At the time in the early 1970s, the 350 twin was at the top of the charts for four-stroke power. The Sport put out 41.7 hp at 8500 rpm and the standard model made 37.5 hp at 8200 rpm. The Sport easily revved over 10,000 rpm—pretty high for an engine of this type—and paired with the six-speed gearbox the bike could easily hit 100 mph.

Dialing up the performance

Later ‘versions of the 3 1/2 would wear cast wheels by Grimeca with disc brakes up front and drum brakes retained at the rear. The 350 twin would go on to become the basis for developments for privateer racers as well as Moto Morini itself. First attempts by tuners were to increase the capacity to over 400 cc, and it wasn’t long before Franco followed suit, taking the factory engine up to 478 cc and fitting it into the Sport chassis.

Further adjustments to the engine resulted in the Moto Morini 507, which was developed for the use in Enduro bikes. The result was the Camel 501 with 71-mm Nikasil-plated bores and updated short skirt pistons, allowing the engine to rev like its predecessors while providing increased capacity and power. The larger capacity made the 507 taller than its predecessor but the weight remained about the same. With larger cooling fins and a design that stuck to 350’s lightweight and compact philosophy. In the case of the Camel 501, the dry weight was 335 pounds—lightweight when compared to one of the forefathers of enduro motorcycles, the BMW R80 GS that weighed in at 410 pounds.

Franco’s final evolution of the twin was a 500-cc turbo which produced 80-hp-plus. Unfortunately, in part due Gabriella Morini’s declining health, she didn’t want to take on any new developments. Amid struggles in the early 1980s that included falling sales, the company sold to the Castiglioni brothers’ Cagiva Group in 1987. The brand withered under Cagiva, but to this day there are Italian bike enthusiasts that enjoy and fondly remember the golden days of the Moto Morini 3 1/2.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

My biggest mistake was selling my 31/2 sport and 31/2 Strada. Oh well.

Hi Steve,

I was just reading your comment on this forum and I wanted to reach out to you and say that IF you are interested I have a 31/2 that has been in storage for 15 years plus and looks like it is in really good condition. Obviously it is not running but for its age it is in really good condition.

For more information . pictures etc drop me an email. larrymuller157@gmail.com

I am in the Netherlands.

Regards

Larry

The combustion chamber moved to the top of the piston is very unique! This Heron design should be looked into by more hotrodders! I love this story

You say “The cams were originally driven by a toothed belt, but later variations of the engine would use gears for the timing—an innovative design.” I’m not sure which you mean – a toothed belt would certainly have been innovative at the time, but sets of gears to drive the camshaft were certainly passe. My ’66 Ducati had an overhead cam driven by two sets of bevel gears. The flathead Ford V-8 (which came out in ’32) had gears driving the camshaft.

Talking of the right-hand gear change as being British is incorrect. Only Japanese bikes had left-hand gear changes at this time, though the standards of controls act was about to force it on any manufacturer who wanted to export to the United States.

A couple of things:

I don’t believe any of the 3 1/2 engines ever had gear-driven cams, belt from the beginning of production to the end as far as I know.

Right-side gear change on early models, but left-side kickstart on all of them.

“…the prototype motorcycle first wore “350” on the oil tank” No oil tank – wet sump. The 3 1/2 badge was on the sidecovers.

I’ve restored one Sport for a customer and the second is in progress. Total restoration of my own ’77 Strada. Have owned two 350 K2s and a 500 Strada.

Moto Guzzi used the Heron head design on it’s own line of small bikes, but never as successfully. Morinis can get phenomenal gas mileage (80 mpg) and make very good power for the displacement. Not so for the Guzzis.

BARN FIND !!

If this forum is still active I have discovered Motorini 3 1/2 in my father in laws gargae which has clearly been stored away for atleast 15 years plus. It is currently not running but for the overal condition I am really impressed. I have no time to get this beauty running unfortunatly so it is for sale. For more information or pictures. Please get in contact with me – larrymuller157@gmail.com

I am located in the Netherlands.

Thanks

Regards

Larry