Stock Stories: 1967 Norton P11

With custom-bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of early two-wheeled machines are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

The Norton P11 is among the rarest and most sought-after motorcycles of the 1960s. At the time of its release in 1967, it was advertised by Norton’s U.S. importer, the Berliner Motor Corporation, with slogans such as “Dynamite on wheels!” and “The world’s finest all-purpose motorcycle.” It was a bike specifically aimed at a riding audience keen on both performance and adventure. Adapted from the Norton Atlas and Norton/Matchless N15CS and G15CS models, Norton envisioned the P11 as a motorcycle for desert racing.

The sport had been active in North America since the early 1920s, popularized in part by high-profile competitions such as California’s Big Bear Motorcycle Run. Desert racing only increased in popularity in the following decades, and by the 1950s events could attract 500 competitors—all in need of competitive motorcycles. At this juncture, British vertical twins (mostly Triumphs) were dominating the sport. Manufacturers could prove the durability of their machines as they tackled hundreds of miles of desert terrain and hard riding. Success in racing would inevitably result in more bikes sold to active competitors, cementing a model’s reputation and in turn better sales in the public.

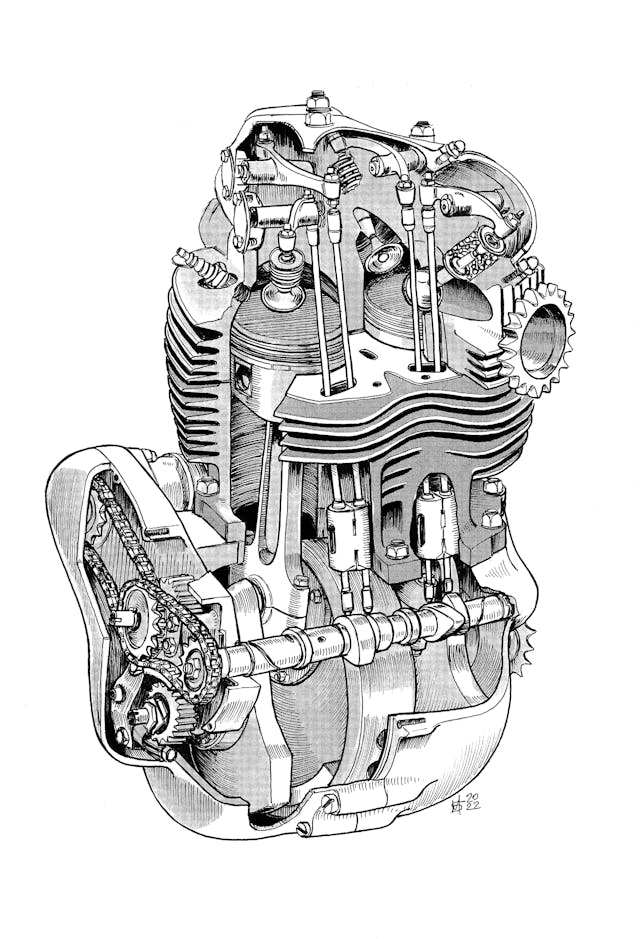

Norton produced a small run of a U.S.-specification desert racer, called the Nomad, between 1958 and 1960. Sold to privateer race teams, the Nomad used the reliable Norton 600cc engine, which succeeded in showing up the Matchless G12 CS scrambler that suffered issues with its three-bearing crankshaft. Norton then upped the ante and increased displacement to 750cc for its Atlas engine—a simpler and more rugged design which proved reliable and produced a decent amount of power. Norton’s ambitions were soon outgrowing the capacity of its Bracebridge Street works, which kicked off the search for a new factory. Parent company AMC (Associated Motor Cycles) had other ideas and moved Norton to the existing AMC facility in Plumstead in 1962. This decision had long-term implications; suddenly, all under one roof, AMC could add the Atlas engine, Norton gearbox, and Roadholder forks to its own bikes. Norton-AMC hybrid machines started to materialize from the London-based company.

For 1964, a batch of 200 Atlas scrambler models named the NC15CS were sent to American distributer Berliner Motor Corp. When the NC15CS hit U.S. soil it was the most powerful off-the-shelf desert racer you could buy. A fair amount of these scramblers were destined for desert racing privateers on the west coast, by way of Berliner distributer ZDS Motors of Glendale, California. It was an important step, and the Atlas motor put out a fair amount of power, but the the frame and overall considerable weight worked against the NC15CS. AMC’s next big leap came for 1966—a lighter version of its ten-year-old Matchless G80CS model, developed to compete in a televised scrambler event on the BBC’s Grandstand. Dubbed G85CS, the new bike used a lighter-weight Reynolds 531 frame which took notes from the Rickman design with a one-piece head stock and frame tubes that were pressed into the head stock and brazed. Together with all-aluminum tanks, lighter Teledraulic forks, and skimmed hubs, the weight was trimmed down to 318 pounds—some 40 pounds lighter than the G80CS. Despite all this, within Europe the G85CS was already being outclassed by the two-strokes which were dominating with high revving engines and lightweight frames. Only 96 G85CS were made and 70 of them immediately went to the U.S. West Coast, where the desert racing crowd would eat them up.

One such customer was Steve Zabaro, mechanic and parts manager at ZDS Motors, who rode his G85CS extensively until he hit a rock in the Mojave Desert, collapsing the front wheel and bending the forks. Understanding the potential of both the powerful NC15CS and the lightweight G85CS Zabaro and Bob Blair (owner of ZDS Motors) deduced that a combination of the two could be a winner. AMC thought it wasn’t possible, but Berliner was happy for Blaur and Zabaro to build a prototype. Just in case.

They got to work on what would ultimately become the Norton P11. Zabaro donated his defunct Matchless G85CS as a donor for the frame, rear magnesium hub, handlebars, and seat. New Teledraulic forks were installed with an Akront 19-inch rim laced to the Matchless hub. The engine and gearbox came from a brand-new N15CS with various spacers and plates fabricated to get the Atlas engine to line up perfectly. Whereas the G85CS had a fiberglass tank, Blair deemed the Norton Steel tank a nicer-looking piece. Most of the parts were off-the shelf apart from the oil tank, which was made by local racer and fabricator Paul Crowell; Zabaro welded up the high-rise exhaust system. The build took three weeks and the initial tests showed great promise. Seasoned racer Mike Patrick put it through its paces in the desert and was very impressed with the prototype, finding it very capable. He suggested AMC change almost nothing for final production.

The prototype was called “Project 11” and displayed at the Earls Court show in 1966, where it caught the attention of Dennis Poore, the new owner of Norton-Villiers. He was so taken with the P11 that he pushed it into production in 1967. Norton developers implemented some changes for the production version, largely for the better. Modifications included a switch from magneto to twin coil capacitor ignition—a first for Norton. Amal Concentric carburetors were also used instead of the older Monobloc units, all in the name of better performance and reliability. “Cheetah 45” was tossed around as a possible name in pre-production, but the Project 11 prototype name was soon abbreviated to P11 and that was that.

Those high up saw the obvious financial advantages of using up existing stock to build the P11. With essentially all the parts on the shelf already, there was no costly development to be done—just some assembly and marketing. Less investment meant more profit, which was essential for struggling AMC. (As production went on, the P11’s specifications changed slightly depending on available stock, which makes tracking subtle model updates tricky for historians and restorers.)

Buyers in 1967 must have been chuffed to be able to lay their hands on the same lightweight frame and engine arrangement as the prototype, along with a solo seat and high rise exhaust which maintained the P11’s iconic off-road look. The tin work was coated in a candy apple red and the tank had the round Norton badge with grey pin stripes. Less obvious improvements were the weight-saving skimmed hubs and forks with off-road internals; after all, this was an “all-purpose motorcycle” and Berliner was advertising it to the public with capability front and center.

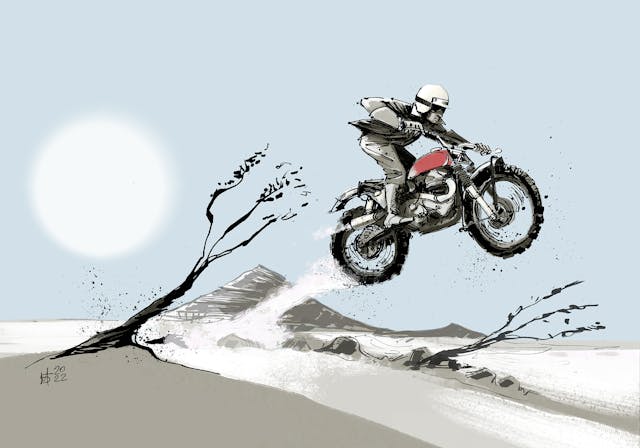

With the first batch of P11s delivered to ZDS, test rider Patrick got his pick of the bunch for the P11’s desert run in which it could prove its worth. Patrick made his own modifications, including changing out the Teledraulic forks for his preferred Roadholders and extending the rear swinging arm by an inch and a half. Both changes improved handling, with the latter helping with stability at speed. Larger, more serviceable air filters were fitted at right angles to the carburetors while a more rugged oil tank was fitted to handle abuse in competition. Patrick was clearly on to something, because he went on to win the heavyweight championship in 1968 on his P11. His victory proved the ability of both rider and machine, and blooming P11 sales certainly made Berliner pleased.

1968 would be the final year for competitive four-stroke twins in desert racing. Having ridden out the last of the desert competition with the P11, Norton looked to improve practicality for its successor, the 1968 P11A. Designed primarily as a road-going machine, the P11A benefited from low-slung pipes with an upswept back section—an aggressive styling decision which was a first for Norton. The exhausts also featured removable end caps and baffles, and Norton extended the seat to a wide dual seat for more comfortable touring with friends. Initially the P11A retained the alloy front mudguard that tended to crack under stress, so dealers would often replace them with chrome versions; it wasn’t long before AMC did the same on the production line. Like its predecessor, the P11A was another exercise in using up parts from the AMC bins. It came in a non-chromatic blue as well as the standard candy apple red.

The P11A became known as the Ranger by the end of 1968, but Norton only built it until November of that year. It is distinguished by the painted Norton decal on the tank and its stainless steel mudguards.

These are rare bikes built over an extremely brief span of time. With 2500 P11s made over a 20-month period, the P11 can be seen as a flash in the pan. But with its roots in desert racing and its superior power-to-weight ratio, the Norton P11 is a seriously desirable motorcycle among those with an affinity for off-road racing. Its hybrid components are also a fascinating example of Norton’s tie-in with AMC, all of which planted the seed for the Commando that followed.

I remember Mike Patrick winning on his Norton in the Mojave desert. He could make it sing. I am 87 and still remember it.