Stock Stories: 1958 Honda Super Cub

With custom bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of the two-wheeled machines that first rolled off of the production line are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

“You meet the nicest people on a Honda” is by now a tagline synonymous with the Japanese company’s two-wheeled golden age. For good reason, too: The Honda Super Cub, for example, was a small-capacity wonder with big-time ambition to go with its friendly personality.

After WWII, many countries set to work repairing their infrastructures. With fuel in short supply, people had to commute to work on a budget. A solution, in many countries, was the manufacture of motor-powered bicycles. Japanese companies began buying up power units from abroad as a quick solution, but the cost of importing these motors raised the price of the final product out of reach for the average Japanese post-war buyer.

Soichiro Honda, who founded Honda Motor Co. in 1948, had a vision for making these machines more accessible. Using an in-house two-stroke engine design, Honda released its first powered bicycle, the Cub F, in 1952. It was a solid success that helped establish the brand’s position in the marketplace, and other experiments followed, Larger-capacity machines were suitable only for a limited number of riders, and lower-capacity offerings like the 1954 Juno scooter proved underpowered and overly complex.

By the mid-1950s, demand was rapidly shifting away from powered bicycles. In order to revive the Honda stable, Takeo Fujisawa, co-founder and business mind of Honda, seized upon the idea of a small high-performance motorcycle. Out of it would ultimately emerge the Super Cub, a now-iconic bike that would prove essential for Honda’s long-term expansion plans around the globe.

For Honda and Fujisawa, the essential goal was to produce a motorcycle on a large scale that could be used by anyone, throughout the developed and undeveloped world, in both rural and urban areas. During their research trip to Europe in late 1956, Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa witnessed the popularity of mopeds and lightweight motorcycles, but their visits to showrooms—including those of marques such as Kreidler and Lambretta—convinced Fujisawa that Honda’s revolutionary bike demanded several key changes.

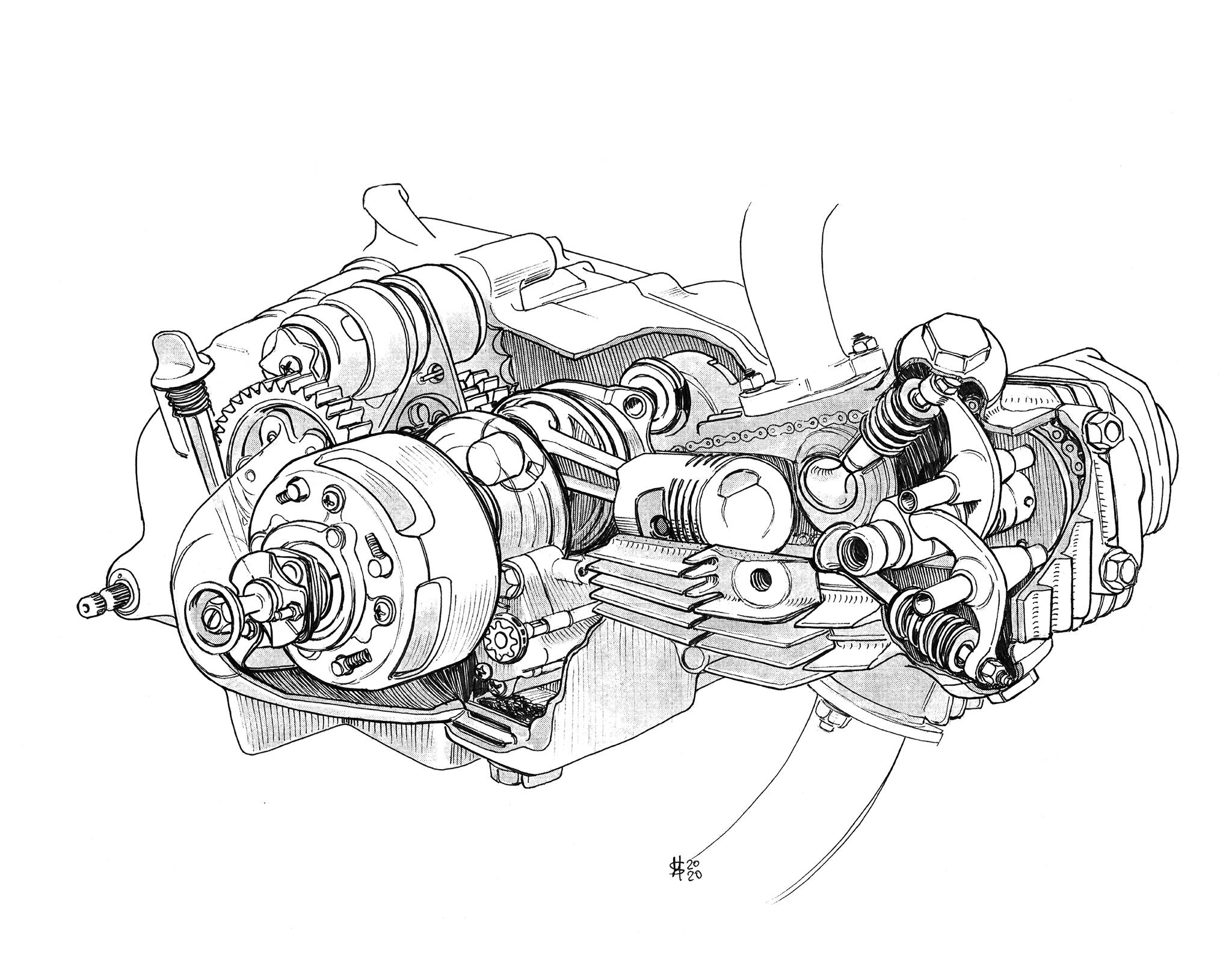

For one, Fujisawa successfully lobbied for a four-stroke engine, mounted in a more traditional way, that promised quieter operation, ease of maintenance, and super reliability compared to a two-stroke. Bigger wheels were essential as well, given that a scooter’s small wheels would never suffice on Japan’s relatively undeveloped roads. It was decided that a happy medium of seventeen inch wheels would be ideal, even though such a size was not an off-the-shelf option at the time. When Honda approached major tire manufacturers, they refused to develop a tire for a single model, deeming it commercially unviable. After a while Honda found a local small manufacturer to take on the task, but until the tires were available the team at Honda had to sew existing eighteen-inch tires to fit to the seventeen inch hubs for the prototype. One of the many examples of Honda’s can-do attitude.

A quite specific—and now famous—requirement was that the motorcycle could be ridden with one hand so that the other could carry a tray of soba noodles. (Similar to the Citroën 2CV having to carry a basket of eggs across a field.) Honda wasn’t being cute, either. This prescription was practical: Delivery riders at the time in Japan were riding bicycles one handed whilst carrying orders with the other in precisely this manner. Another practical development to this end was that of a centrifugal clutch which would provide automatic gear changing without the use of a clutch lever, freeing up said hand. In a wider context, these development targets simply made the motorcycle easier to ride for more people.

Another innovation was the use polyethylene resin for the bodywork, rather than the FRP (fiber-reinforced plastic) employed on the Juno scooter. The Super Cub became the first motorcycle to use a plastic fairing, running from the handlebars down below the feet to protect the rider. The fairing also enclosed the engine, making this a very clean machine to ride, and a lighter footprint meant better fuel economy.

When the Super Cub mock-up was completed and presented in the Honda cafeteria in December of 1957, Soichiro asked Fujisawa how many of these he expected to sell. The very confident answer? 30,000 units—a month! Sales figures in Japan hovered around 40,000 motorcycles examples sold each month in total. It must have seemed like a joke to employees, but Fujisawa was deadly serious. Honda (which was selling 2000-3000 motorcycles a month) didn’t even have the means to produce 30,000 machines a month let alone sell them, but Fujisawa had big plans to address that problem. Honda planned to build a new factory in Suzuka—at a risky cost of 10 billion yen—with the capacity to make 30,000 Super Cubs per month; on a double shift, the factory would be able to up that figure to 50,000. Completed in 1960, Suzuka was at the time of its opening the largest motorcycle factory in the world.

Fujisawa also pushed the boundaries when it came to marketing and sales. Super Cub sales were hugely successful for the first three years, with word-of-mouth and the small chain of local dealers handling the initial rollout. The customer base rapidly increased, and by 1960 Honda was selling well beyond Fujisawa’s predicted 30,000 Super Cubs a month.

But in 1961, Honda sent its Super Cub publicity into high gear. At a time when advertising for motorcycles was primarily placed in motorcycle media outlets, Fujisawa ran a large-scale advertising campaign in general interest publications and women’s magazines, in particular. He also instituted a mass mailing operation that involved contacting businesses with community connections, such as grocery stores other merchants. In addition to getting the word out to customers, businesses like these were themselves in need of cheap and usable transport for their employees. Honda’s small, locally focused dealer chain was carefully considered, as well. The design of these shops was intended to make women feel comfortable shopping for a motorcycle, and the Super Cub’s inherently practical design made it appealing to ride.

Success in Japan was one thing, but Honda had its sights set well beyond its own borders. The year after the Super Cub’s release in 1958, American Honda was founded in order to get a foothold in a much bigger, more challenging market. Sales of such a relatively small-capacity bike weren’t great at first; a culture accustomed to big, tough-looking motorcycles was an entirely different animal. Not put off, Honda introduced new models (including a mini-trial, among others) to cater to the American market, although the Super Cub had to be called the 50 because of trademark conflicts with the Piper Super Cub aircraft. Again, mass mailing and advertising campaigns were a major strategy for getting the word out beyond the traditional motorcycle fraternity.

The most famous of these advertisements appeared in North America 1963, in major publications like LIFE and Time, with the slogan: “You meet the nicest people on a Honda.” Images of regular people in clean clothes riding this new, affordable machine actually instigated a change in the way motorcycles were perceived in America. Sales to both men and women increased and 84,000 units were sold in America that year, just five years after the Super Cub’s original debut in Japan. After the boom subsided and fizzled out, Honda ultimately discontinued the Super Cub for the U.S. in 1974, before bringing it back in 2019.

By 1964 Honda had truly gone worldwide, expanding to Europe and then Asia, with factories in Taiwan and South Korea and a distribution base in Thailand. The Honda Super Cub range has become the most produced motorcycle in history, continuously manufactured since 1958. Cumulative volume hit 100 million in 2017. Not only is the Honda Cub an incredible success story in terms of its ambitious volume, but it is truly a great example of how engineering, design, marketing, and sales came together in a truly groundbreaking package.