In the Moment: Sweet lord, it’s the Rollie Free shot

Welcome to a new weekly feature we’re calling In the Moment!

This all started in Slack, the messaging software we use for staff communication. Several weeks ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each photo he dropped into the conversation was accompanied by a bit of caffeine-fueled explanation.

We liked these drops a lot, so we’re sharing one here each Thursday. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

**

Bonneville is one of those places you do not forget. The salt is so wide and white and uniform that depth perception goes momentarily hinky. If the flats have not been flooded by recent rain, they will look like snow. The surface is hard and crusty when dry, a spreadable paste when moist, and a Dead Sea soup when in flood.

People have used it for engine-powered record-breaking for almost as long as we have had engines and records.

In the Moment usually lingers on one image, but the shot at the top of this post is unique. It carries story but lacks detail. Let’s briefly switch to another photo.

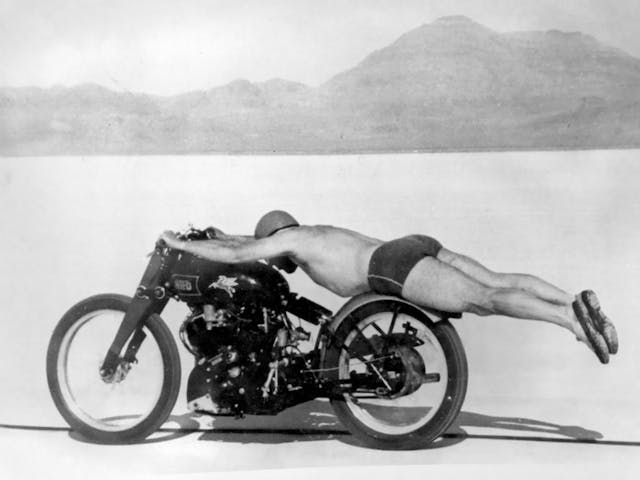

The man in dark clothes is the same one from up top: Roland “Rollie” Free. In 1950, when this picture was taken, he was 49 years old. He is at Bonneville, in front of a Vincent Black Lightning, the same model of motorcycle he is riding in the top image. It is a two-cylinder, chain-driven, girder-fork, 70-hp English device. The moment captured by this photo was not the first time Free had taken a Vincent to the salt.

Four decades later, an Englishman named Richard Thompson wrote a piece of music. Sharing that music while discussing Vincents is stout cliché, but to hell with it, life is short, we don’t cover Vincents often. Plus, it’s a good song.

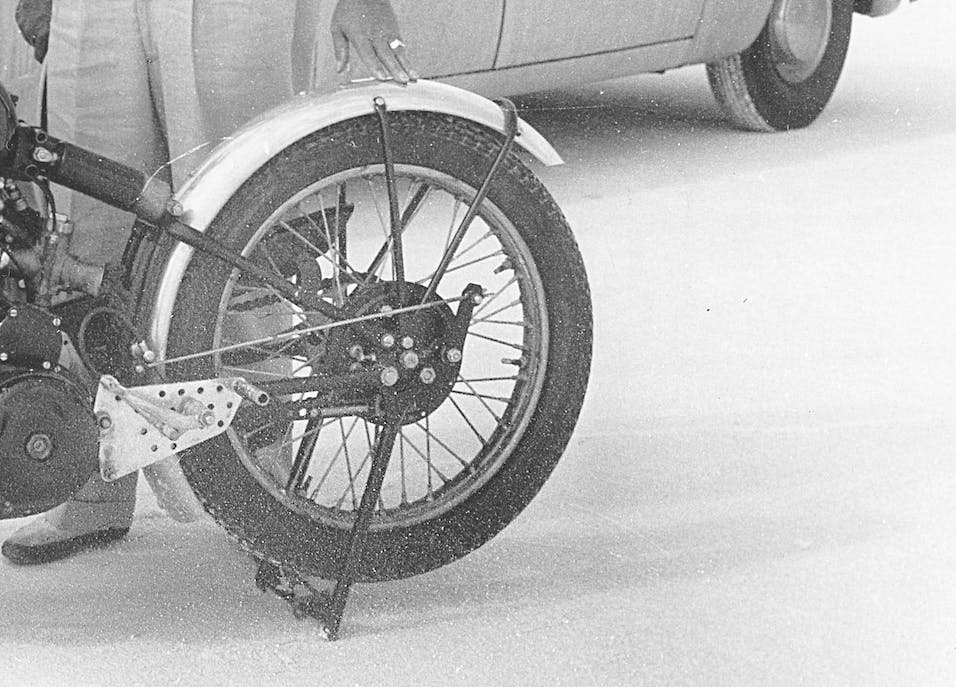

I suspect Thompson could look at Vincents forever. So could I. This Vincent, double forever. Note the Mobil “pegasus” on the tank. Note, also, how there is no seat or front brake. The cylinder between rear fender and fuel tank is the rear spring-shock assembly.

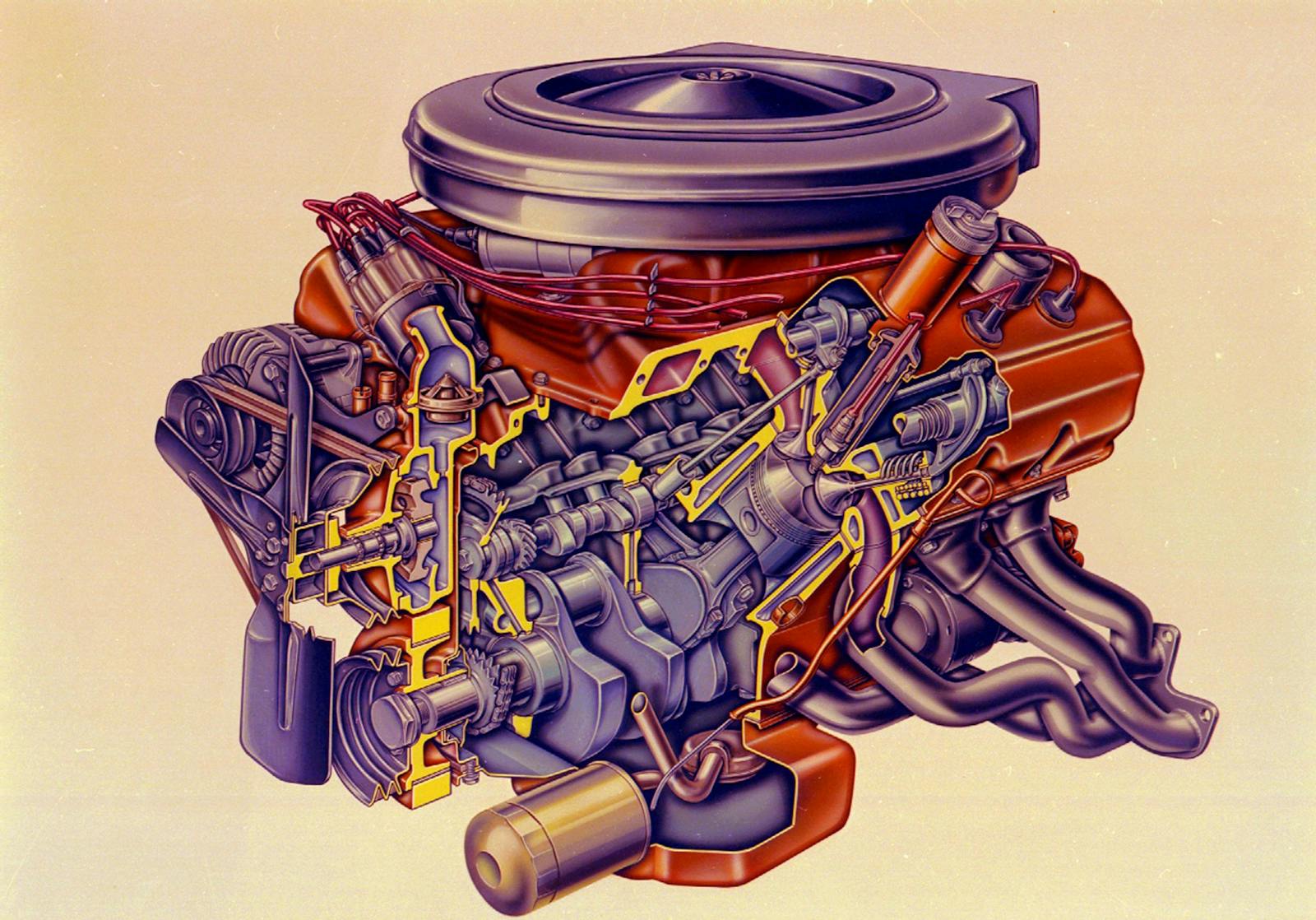

There is so little to the thing! The engine is the engine, obviously. Two finned cylinders with a gearbox and primary drive underneath. But there is no frame beneath that assembly. There isn’t much of one above it, either; the frame on a postwar Vincent twin is mostly just the oil tank, which lives under the gas tank. It looks like this.

In load-bearing terms, that tank is trivial; the engine literally holds the bike together. Its case was designed to be fed suspension load, steering load, the heft of a rider, everything. Remove the powerplant from certain Vincents, you have no more Vincent.

This practice is known as stressed-member construction. Done right, it saves weight. It has been used in motorcycles and racing cars for decades. In 1948, however, the idea was not widely trusted or understood. Most motorcycles then used “cradle” frames, the engine carried in a perimeter of load-bearing steel tubes.

So. The Black Lightning. On one hand, we have that forward-think layout. On the other hand, there is that lightly prehistoric front suspension. Those two long vertical pieces on each side of the wheel—the “girders”—are tied to each other by two horizontal links running forward from the tank. One shock lives behind each girder, angled to the rear.

Seen from the side, the girders and their links form a box. On a Vincent, a coil spring sits in that box, above the bottom link and between the girders. Remove the spring, the front suspension will collapse.

Those circles on the fork and its links, silver in the black, represent the pivot points.

If none of that makes sense, watch this.

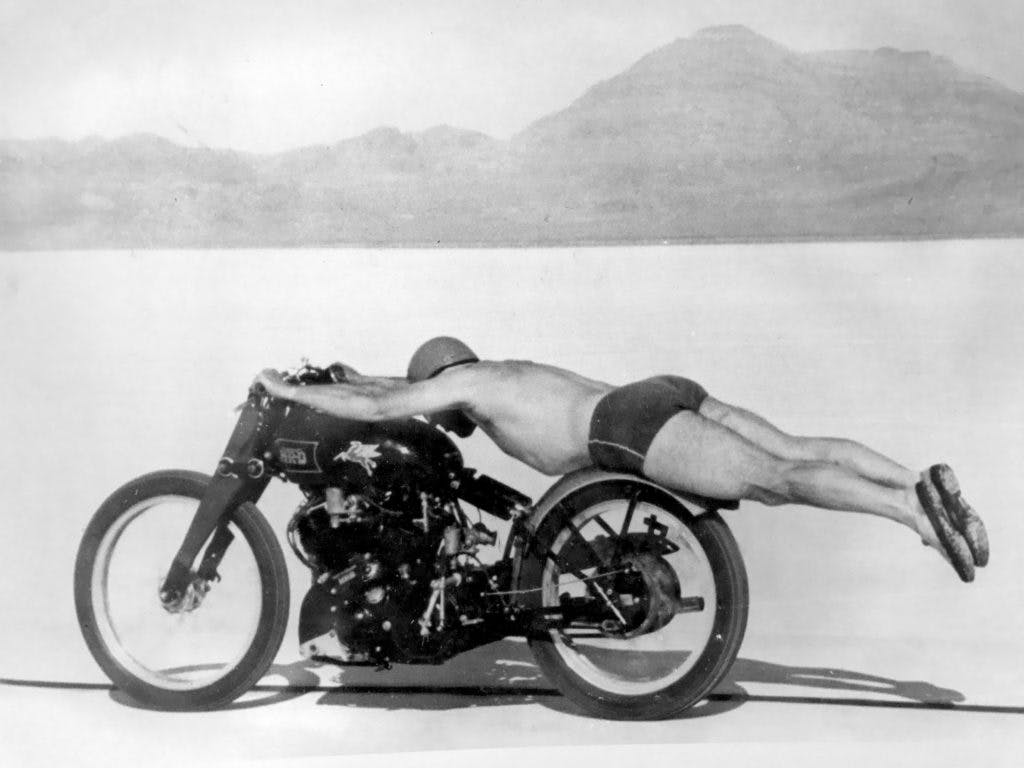

Back to the top photo. Again, that is Free, in 1948, same salt, same model of bike. This image has been called “the most famous picture in motorcycling.”

Back to the top photo. Again, that is Free, in 1948, same salt, same model of bike. This image has been called “the most famous picture in motorcycling.”

Look at the salt stuck to the bottom of his shoes! Look at the helmet! The helmet is comical! The man is virtually naked, riding across what might as well be the world’s largest piece of sandpaper, and he is so concerned about safety, he is wearing a helmet.

As a young man, Free worked in motorcycle retail and began racing. In World War II, he was stationed in Utah, with the Army Air Force, and he saw Bonneville for the first time. After the war, he went back to competition. He grew familiar with Vincents and developed a relationship with their maker.

Philip Vincent grew up in a wealthy family of cattle farmers. In 1925, while in school at this place, he began building a bike of his own design. Three years later, he decided to make motorcycles for the masses. He bought a defunct English bikemaker, HRD.

British motorcycles of the time were often designed around bought-in parts. A marque’s engineering head would call an engine company for engines, a gearbox company for gearboxes, and so on. Vincent did this at first. His bikes were used hard, however, and they broke. In the early 1930s, he hired a man named Philip Irving as chief engineer. The two men grew tired of all the breakage. In 1934, in a moment fit for the movies, they entered three factory race bikes in the Isle of Man TT. Mechanical trouble downed all three.

Screw it, Vincent said: He and Irving would make their own engines from scratch.

The bikes were called Vincent-HRDs. Later, they would simply be Vincents. At first, they wore relatively durable single-cylinders. One day in 1936, however, Irving was working in his office. Two engineering drawings of a company single, he noticed, had been casually laid over each other on a table. Their shapes made a V.

Ah, he thought: a V-twin. And so that engine soon appeared, in a new, 1.0-liter Vincent, the 45-horse Rapide.

War paused everything. When Vincent production restarted in 1946, the Rapide had been improved. The engine and gearbox, formerly separate components, now shared a single, stiff case. Critically, the bike had lost most of its frame—that stressed-member idea—and 1.5 inches of wheelbase. Ads called it “little big twin”: the size of a 500-cc bike, the power of a full liter.

There was a hot-rod model, because of course there was. It made such a dent in humanity that good examples are now worth six figures. The 55-hp Vincent Black Shadow, launched in 1948, received more compression, polished rods, larger carbs, and so on. The engine cases, once bare aluminum, were now black enamel. Top speed went from 110 mph to more than 125. It was the fastest production bike on earth.

At this point in history, the world’s popular motorcycles essentially fit into two groups. American bikes were durable but generally heavy, built on cubic inches. European bikes were mostly lighter and more nimble; the English in particular placed a priority on healthy power from small engines. The Black Shadow was essentially the two ideas crashed together.

My favorite part of this lore: In 1948, many motorcycles could not reach 100 mph, the myth-laden “ton.” The Rapide’s speedometer stopped at 120. The Shadow’s main clock was this five-inch, 150-mph Smiths pie plate used on no other bike. The 100-mph mark wasn’t even labeled. It wasn’t a destination.

The Black Shadow gained a reputation. People saw it as a mystical idea, a figment. It was in reality a locomotive, Harley grunt plus good handling and brakes, with virtually unbelievable numbers. Add to this the traditional British motorcycle aesthetic—deep plating, artful castings—and people went nuts. Californians in particular.

Back to Rollie Free. In the late 1940s, he is friendly with a West-Coast racing enthusiast named John Edgar. He convinces Edgar that a tweaked Black Shadow would demolish the American motorcycle speed record, then 136 mph. Free writes the Vincent factory and proposes another hot rod. Vincent the man is interested. Irving engineers and builds the bike in just ten weeks. Edgar pays for it. It is stripped and massaged and runs on methanol. George Brown, in Vincent’s comp department, hurries to a nearby airfield for testing. He comes back and tells Vincent that he saw 143 mph, engine still pulling, before he ran out of runway.

The machine is shipped to Los Angeles. Free takes it to Bonneville. Mobil kicks in funding. The world does not get excited, because almost no one is told. On the salt, stretched across the bike’s rear, Free lays flat, to minimize drag. He wears motorcycle leathers.

An early run produces 147 mph. This is deemed too slow. Nonplussed, our man sets those leathers aside.

Remember: The previous record was just 136 mph.

What followed beggars belief. If photographs did not exist, the specifics would have long ago been chalked up to hype and tall tale. But our man . . . our 47-year-old man . . . that barrel-chested and balding American . . . my dude in the fantastic leather boots . . .

Well, this dad-bod bad-ass simply got back on the bike. In a bathing suit.

Clarification: There was also a pair of sneakers.

One hundred and fifty miles per mother-of-God hour on that seatless motorcycle, mostly naked, at a time when ordinary citizens did not, could not, easily go that fast or faster by simply walking into the nearest Honda dealer and putting a CBR on some overheated credit card. Free had laid on a bike in that manner before, but this was different. He reset that land-speed record. Shortly after, Vincent made Free’s hot-rod spec a production model, the Black Lightning. The new fastest in the world, replacing the other fastest, the thing from which it was built.

Several weeks ago, I walked into my kitchen and saw a glass of orange juice I had left out, overnight, by accident. I grabbed the glass out of habit, raising it to my mouth, then paused.

“Probably shouldn’t drink that,” I thought. “Bad odds.”

Modernity has made us all weenies.

We all choose to take risks. A select few of those risks are compelling enough to be remembered after we are gone. They stand apart from their background, dense with story, like that vast pan of salt. The salt is shrinking, but it will still outlive us all. The choices, on the other hand, are only around while we have time to make them.

It is enough, I think, to simply be reminded that we should, to coin a phrase, occasionally just drink the juice.

Have a good day, guys!

—Sam

Rollie Free and Burt Munro, two wheeled legends at the salt.