CERV-1 replica pays tribute to one of Zora’s wildest rides

In the 1950s, my dad landed a job at Chevrolet Engineering, in the brand-new GM Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. Dad was one of two Chevy Engineering transmission techs.

One summer day in 1959, the department held an employee open house event, and Dad took me to the Tech Center. I was 7 years old. I remember the fountains, the Design Dome, and the turbine cars that looked like spaceships.

Near Dad’s work area, around a privacy curtain, propped up on a white platform, was the neatest little car I’d ever seen: the Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle No. 1, or CERV-1, sans body. Dad introduced me to two men standing nearby, Zora Arkus-Duntov and Mauri Rose, then plopped me in the car’s metallic blue driver’s seat. I played with the controls, and at that moment, I became a car guy. Nearly 60 years later, I built my own CERV-1.

The mid-engine configuration was state-of-the-art in 1959. It had taken over Formula 1 and was being considered for Indianapolis. Understandably, Arkus-Duntov wanted to investigate the performance of such a layout, and the CERV-1 was his mule. Tests at the GM proving grounds and several racetracks (including Sebring, as covered in Sports Car Graphic, May 1962) showed its potential. Arkus-Duntov campaigned for a mid-engined production Corvette, but manufacturing costs and conservative management halted his plans.

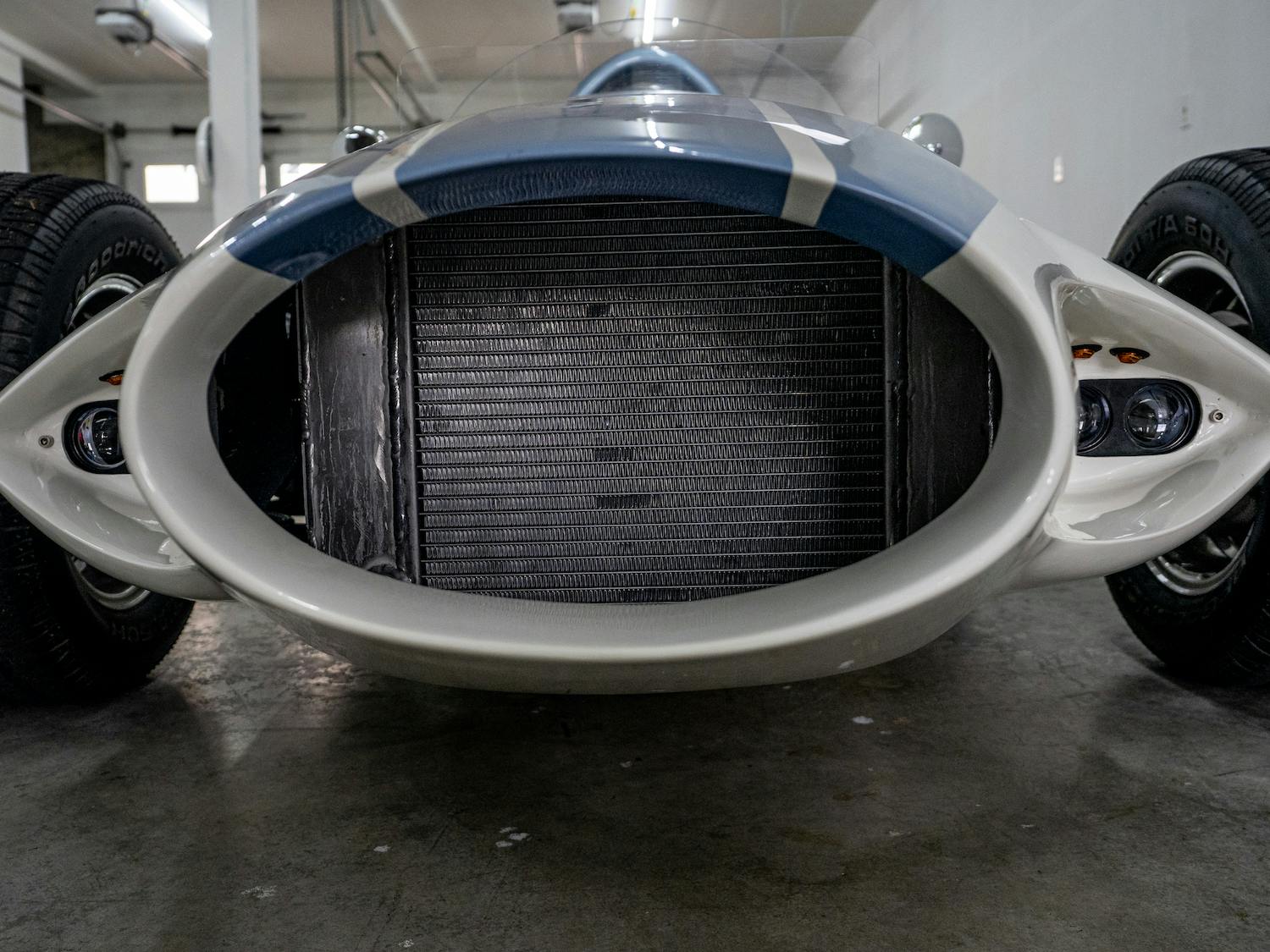

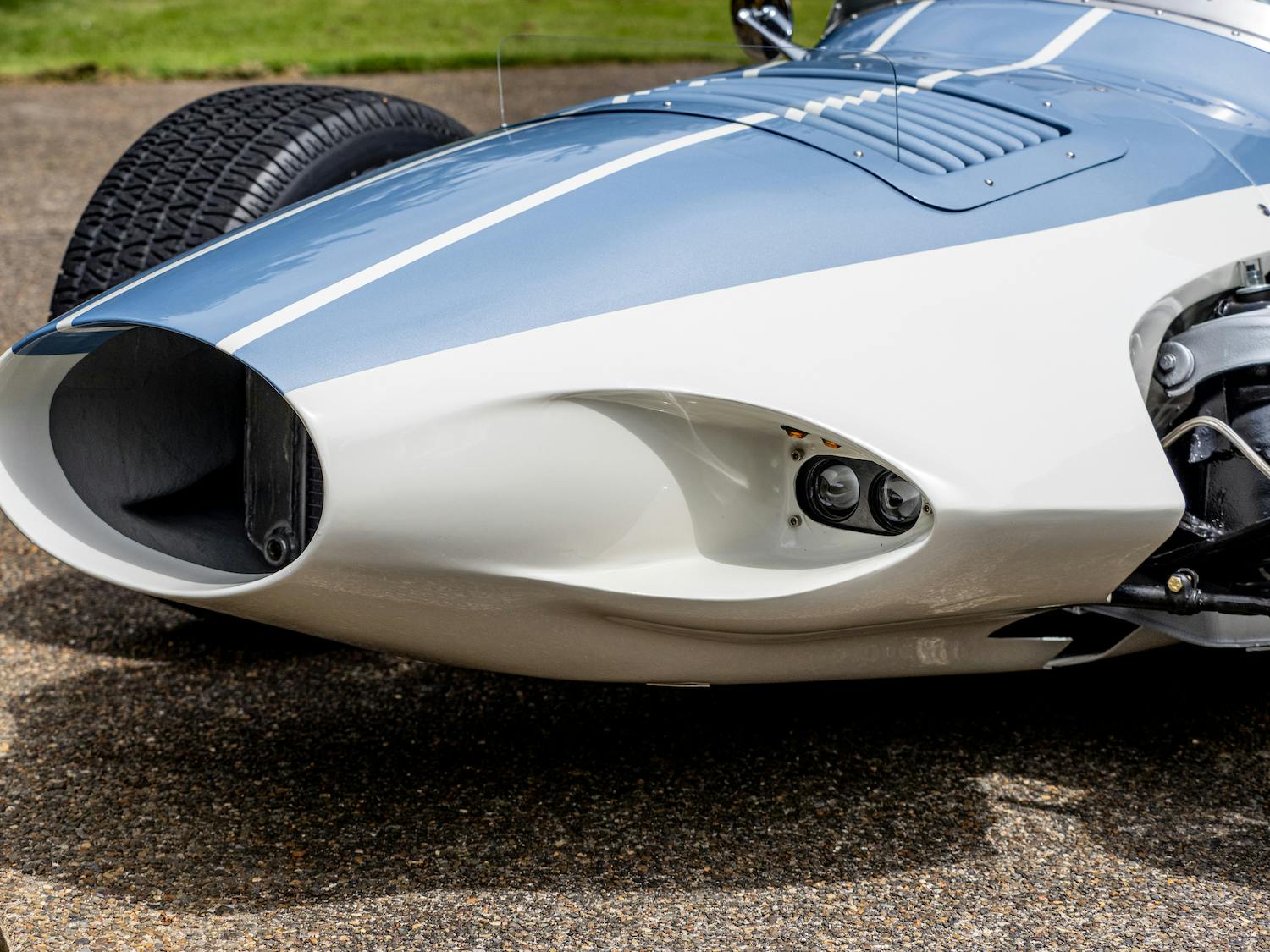

The CERV-1 had a body designed by Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine, with side pods, a headrest/air scoop, and a profile that resembled a stingray fish. Several first-gen bodies of slightly different styles and finish were installed on the CERV-1 chassis. My build uses the earliest body style, plus some artistic license. (This early body no longer exists; the car in the GM Heritage Collection sports a late body.) I mixed it up a bit more with a paint scheme of late nose blending to early tail. This Frost Blue Poly over Snowcrest White showed up for testing at Sebring in ’62.

The first step in reverse engineering is to gather all the data you can find on the subject. Fortunately, GM shared development photos with journalists throughout the ’60s, and I was able to find all the CERV-1 pictures and articles I needed.

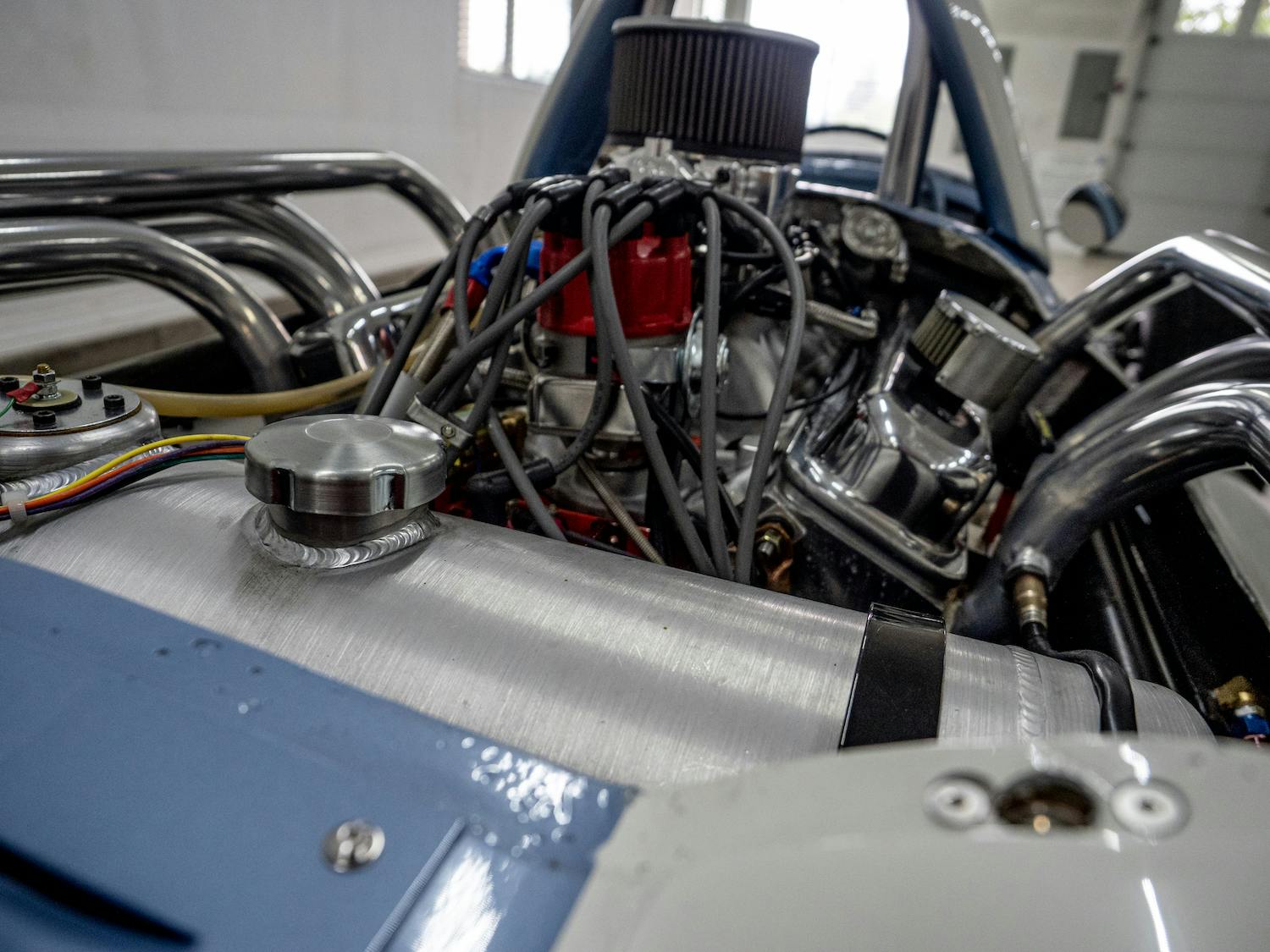

Period photos show the tubing layout, but before I could design the chassis, I needed the key parts: engine; transmission and quick-change differential; front and rear suspension; seat; and suitable wheels. The engine and seat were easy—a small-block Chevy and a Kirkey. The CERV-1’s independent rear suspension (IRS) made its way into the 1963 Corvette, so I picked up an early IRS and rebuilt it. There were no transaxles available to Arkus-Duntov that could handle a hot V-8, so his team replaced the tail-shaft housing of a four-speed with a Halibrand V-8 quick-change differential. I designed and machined an adapter mating a Saginaw case to a Champ IRS quick-change. My quick-change is narrowed to Corvette IRS dimensions using Speedway Engineering Bells, with a Detroit Locker, custom forged axles, bearing retainers, and through shaft. It looks and works just like Arkus-Duntov’s, but stronger.

At Chevy, Arkus-Duntov needed an approved program to bill CERV-1 expenses. The only program in development at the time was the Corvair, and Ed Cole, then general manager, apparently allowed Arkus-Duntov to use some of the Corvair budget. For front suspension, the CERV-1 used a “leftover” handmade piece from the defunct Corvette SS program, with upper control arms that closely resemble those from a Corvair.

Period photos show the CERV-1 with a Corvair steering wheel. I recalled the column and steering box were also from a Corvair, so I junked one to get its front suspension and steering, which I modified to eliminate bump steer. I changed the ride height, improved damping, and added GM disc brakes. My CERV-1 re-creation should handle and stop better than the original.

Using the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) rulebook as reference (and with help from Bonneville tech inspector “Kiwi” Paul Gilbert), I designed a frame in 3D CAD to meet or exceed land speed record specs. My CERV-1 development used 3D models extensively, from the frame and body to the transmission and quick-change adapter.

My frame design looks like Arkus-Duntov’s but has much larger tubes; a full SCTA rollcage bolts on, as well. A lot of time on the computer meant I saved countless hours, frustration, and a bunch of money in fabrication. It’s far easier to cut and throw away a virtual tube than a real one. It took 83 iterations and three years to get it (mostly) right.

From my 3D model, I crafted a body master “plug” and a mold. Starting with the belly pan, I laid up the CERV-1 body panels, trimming each and scribing the mold with wheel cutouts and the like. The wheel wells and headrest/air scoop were separate molds, some being designed quickly for single use.

My test engine was a 355-cubic-inch small-block Chevy with ported Vortec heads, a custom roller cam, 10.5:1 static compression, and several other tweaks. I made stainless-steel upswept headers and had them ceramic-coated, inside and out. Overall, it had more power than the original’s 283. I used the 355 for the initial testing and found it to be quite adequate.

Then I upgraded to a 388 stroker with 12.5:1 compression, aluminum heads, a comp roller cam, and a Holley Sniper EFI. It’s cooled with two large aluminum radiators up front and two auxiliary units in the tail. It was modeled after a 500-hp build and absolutely rocks this little one-seater.

In fact, it’s a hoot to drive. A V-8 go-kart. A 1960s Indy car. Visibility is great, and watching the suspension work is a blast. The cockpit is roomy but short, so your knees are brought up a bit, under the Corvair wheel. The hydraulic clutch is light, and shifting via cables from a modified Hurst Competition Plus is smooth.

Aggressive use of the throttle causes wheelspin—any time, any gear. It’s much faster than I thought it would be. In August 2020, I took my CERV-1 to Portland International Raceway (with the 355) and re-enacted Jerry Titus’s 1962 Sebring test. My test driver complained that he pegged the tach at the beginning of the back straight at 165 mph and wanted a taller gear. With the bigger V-8, this car will do 200. Someday I plan to prove that at Bonneville.

In the meantime, you can see my CERV-1 for yourself, on loan to the National Corvette Museum through late next year.

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

This is a master piece of work. It is one thing to build a customer car but to try to replicate a historic car that really becomes a challenge due to critics like me on those who do not get it right or close to right.

He did a wonderful job here and if it has period correct tires on it could fool many people till they see the dash. Even then many would remain fooled.

I noted the Corvair front suspension bits. While many become critics of parts bin cars it just depends on the parts you use an how you use them.

I am often hard to impress but this more than impresses me. In fact I am down right envious.

“He did a wonderful job here and if it has period correct tires on it could fool many people till they see the dash.”

Yes, the digital instruments had me scratching my head. After Tony Briski took such pains to make it period correct, I’m puzzled why he went with 21st Century gauges.

But I certainly agree that this is an incredible piece of work that commemorates an important car. It’s a shame that the original no longer exists.

Very cool car. I love the look and the details on it.

Had the pleasure of seeing this up close at a cruise-in in Vancouver, WA. Very impressive.

I remember the various press releases of that car. (Yes I am over 75). That car and growing up in the LA area in the 60’s made me a car guy for life. It amazes me how someone can build a car like that using pictures. A friend of mine built a “Bugatti” from a dune buggy chassis in his one car garage.