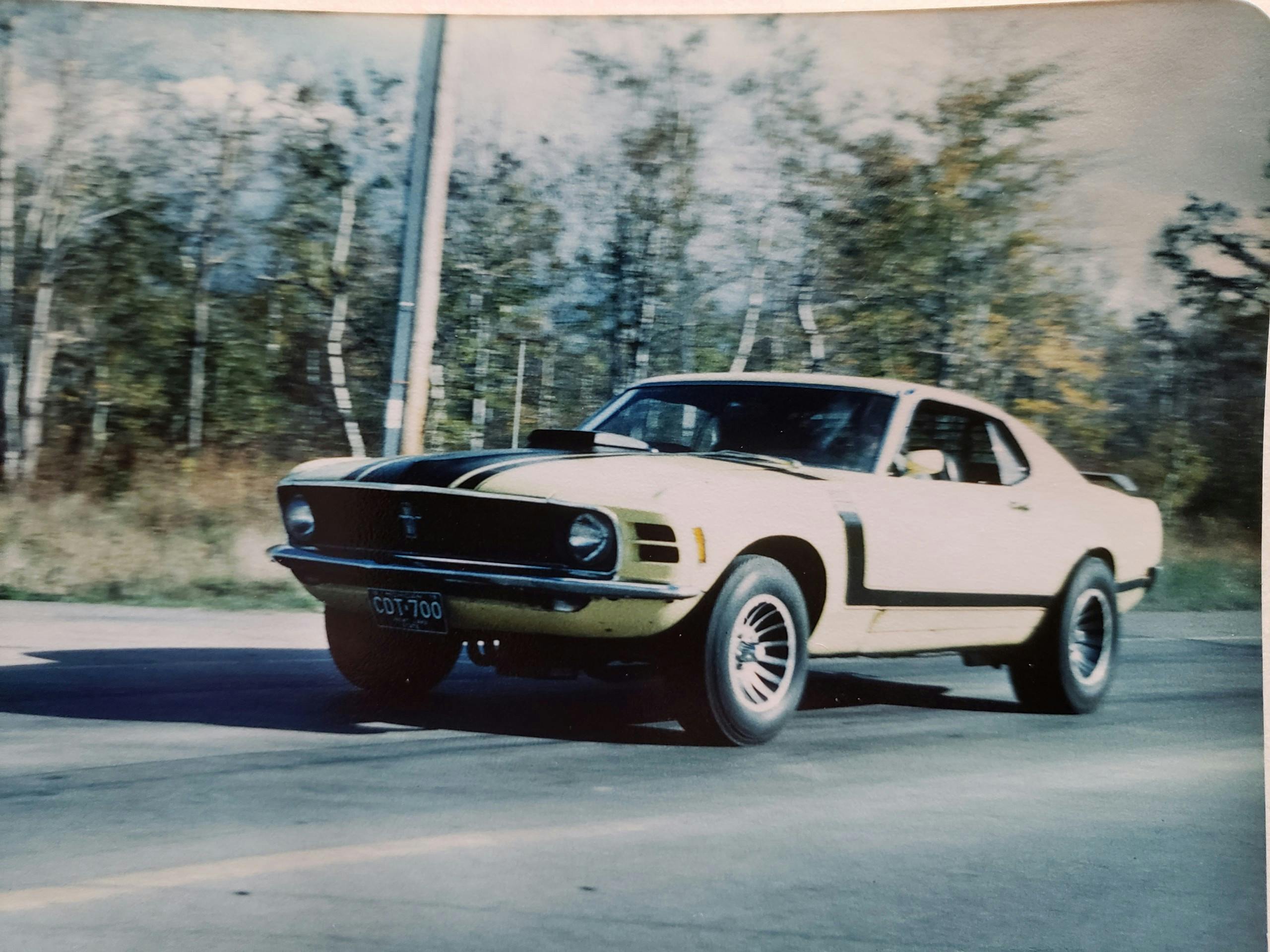

This 1970 Boss Mustang packs a 427-cubic-inch secret

Two Hagerty Drivers Club members, Doug Miller and Joseph Sprague, connected by way of a very special muscle machine. It might look like an ordinary Boss, but under this Mustang’s hood is a little 427-sized something by way of Holman-Moody—and Le Mans. When it came time for Doug to pass the car on, he made sure it landed in good hands. To join the Hagerty Drivers Club, click here.

Doug says:

That Mustang was a rocket, I tell you, a rocket. What a blast. I had the motor of my dreams and a car that was made to handle it. The thing tracked straight as a string and it was as safe as being in your bed at night. Never squirrelly, just outrageous.

Back in 1973, my buddy and I found a 1970 Boss 302 Mustang on a used-car lot in our town of Midland, Michigan. It didn’t sound very good when we started it up, and it read zero oil pressure. So before buying the Mustang, we took it to the Lincoln-Mercury dealer across town where we worked, ran it up on the hoist, and dropped the oil pan to check the internals. The oil pump drive was twisted in half, and there were lots of tiny aluminum pieces in the pan. We gathered the metallic bits up in a nice oily shop rag, went back over to the used-car lot, and dropped them on the salesman’s desk. “Let’s deal,” I said.

Right after I bought the Mustang, my buddy and I pulled the 302. We rebuilt the motor, dropped it back in the car, and I drove it for the next year. That 302 was great for racing streetlight to streetlight, but I wanted to go faster. I had always dreamed of owning a 427 Cobra, from the time I read about one achieving something like 0-to-100-to-0 in like 10 seconds. Well, in summer 1974, a local guy named Mike had this Shelby Mustang with a 427-cubic-inch V-8 in it. All the gearheads around town thought it was a 427 “Cammer” engine. I knew better. This mystery motor was Ford’s 427 FE overhead valve V-8, like the one used in GT40 race cars. The exhaust tube on the third cylinder, each side, crossed under the engine and over to the other collector. It made such a unique exhaust note.

Well, the 427 had started to make a little rattle or something, and Mike decided he didn’t want to mess with it anymore. He was tight with his money, and it was going to cost him big to send it down to Holman-Moody for a rebuild. Instead, Mike decided he wanted to trade the engine for something less radical. We ended up making this convoluted engine swap between three cars—nothing short of a backyard mechanical miracle. In the end, Mike ended up with a K-code 289 in his Shelby, and I had a 427 big-block, the motor of my dreams, in my Boss Mustang.

I still remember the way I was shaking from excitement the day I dropped the 427 into my Boss. Since those ’70s Mustangs could be ordered with a Cobra Jet engine, the engine bay configuration and all of the motor mount locations were ready to handle a big-block.

Midland was a Chevy town back then, and nobody knew what I had. I’d pop the hood, tell them it was the Boss 302, and they’d stare at that big motor, having no clue that it wasn’t. I kid you not. I had so much fun with this car. I think back to my time street racing on Monroe Road, 2 miles out of town. There were a lot of fast cars racing out there—396 Chevelles, 396 Camaros, plenty of pretty fast small-block cars, too. Whenever I’d race my Mustang, I’d let the other guys pull away a little, and then right at the end, I’d zoom right past them. Just nose them out. They’d say stuff like, “Man, that was a great race!” I’d nod and agree, knowing I was sand-bagging the whole time.

To this day, I think back in amazement to some of the things I did with that car. But time passes, and eventually I reached a point where I could see that the car’s future was not with me. A few years ago, I chanced upon Joe Sprague through a mutual friend. We hit it off immediately. I looked at Joe and saw a lot of myself back in the day, when I had the energy to come home from work and go right out to the garage and start wrenching on stuff. We agreed on a price for my Mustang and made the deal.

When Joe gets that thing back up and running, he’s going to have a smile so wide. No matter what I did with small-blocks, it never compared to the big 427. You’d stand on the gas, and this thing, without a hint of hesitation, would roar. I can still hear it. Before long, Joe will know that sound, too.

Joe says:

I was on the road for work, in a hotel room in Houston, and my buddy Randy called me. He told me about a 1970 Boss 302 Mustang with a non-original motor and gave me Doug’s phone number. I remember talking to Doug for the first time, and he’s like, “Well, it’s got a 427 in it, and it has the aluminum heads.” We agreed on a price, and I immediately started researching the car.

I looked up VINs and part numbers, and I interviewed people who worked on the car. It was so much fun reconstructing the car’s history and tracing the engine back to 1967. After two years, my conclusion is this: The 427 was one of 10 blocks sent to race in France at Le Mans with the 1967 GT40 J cars. The engine was unused in the race and sent back to the States. Somehow it ended up at a speed shop in California, and eventually under the hood of a 1967 Shelby GT500. The owner of the GT500 swapped the 427 for a K-code engine, and that’s how it ended up with Doug’s friend, Mike, in Midland. Even though the intake was replaced with a tri-power setup, the big motor has its original aluminum heads, Holman-Moody water pump, and aluminum crank pulley.

Sure, I own the car, but it’s Doug’s story. I still keep in contact with him. Every time I find a new tidbit of information about it, like when I got the Marti Report, I share it with him. I feel like, in a way, it’s really his car and I’m just holding on to it for him. The Mustang meant a lot to him. Anytime you sell something, you’d like to think that whoever gets it after you will appreciate it as much as you did. That’s what I’m trying to do.

Thank you for sharing this great story. I grew up….no, that’s not correct…I was a teenager in the ’60’s. There were awesome cars everywhere. I couldn’t afford one, and didn’t have the knowledge or the tools to work on one even if I did have the money. But, I sure remember the guys who had both. The sights and sounds and odors are still in my head. It was a wonderful time to be young. Thanks again, good luck to you.

Ditto…One of my greatest regrets is that by the time I had the money I didn’t make the time to learn the craft.

All the best..

Unrestored original cars are so much more interesting. I normally prefer unmodified cars, but this is one of those exceptions.

I’d take a boss with a 427. But I’d clean up the car.

They’re called 180-degree headers. Kind of a poor man’s flat-crank engine.

It always amazes me how awesome backyard mechanics can just drop a different motor into cars and fabricate what’s needed to make it work. Probably doing it on their backs with jack stands and no lift! So nice to be young.

“Midland was a Chevy town back then, and nobody knew what I had.”

After a friend who used to race at the local dirt oval switched from Chevrolet to Ford he would tell me he could cheat like crazy like everybody else did and the Chevy guys didn’t have a clue because they knew nothing about his 351W. Of course the Chevy guys cheated as much as they could get away with too but it was harder because all the other racers knew Chevys. Not to rag on Chevy guys but many of you guys need to know this if you ever work on a Ford. Ford cylinders are not even on one bank and odd on the other, they are numbered 1, 2, 3, 4 on the passenger side and 5, 6, 7, 8 on the driver side. I felt compelled to explain that because of the time repairing a misfire on a customer’s Ford I found a new #3 coil installed by another shop to fix a P0303 DTC was installed on the #6 cylinder or another time a Ford was towed to my shop having plug wires crossed because the mechanic at another shop who was an expert Chevy mechanic couldn’t comprehend this. Heck, I think that guy is still wondering why the distributor was in front instead of the back. Of course these are isolated incidents and not all Chevy guys have tunnel vision when it comes to working on brand X. We all have our preferences on our cars so go ahead and cuss at them, I do, but be aware not every engine is a SBC or LS.

This story reminds me of my own adventures with sleepers with 427 engines. Back in the late ’60s, I was a student intern in Ford Engineering in Dearborn. I had a 1968 Cougar with the 428 CobraJet, which was a rare option in the Cougar. It weighed 3650 lbs. and turned low 14’s @ 100 in the quarter. Over time, I replaced the original engine with a 427 Medium Riser, keeping the 428 crank for an added 20 cubic inches. With headers, hotter hydraulic cam and 3.90 gears, it turned high 12’s at 110.

One day I was hit in the rear by some teen running away from the cops, nearly totaling the Cougar. A friend of mine who worked in the Ford Experimental Garage, Ernie Macewen (who built drag cars for Doug Nash including the famous Bronco Buster), suggested that the driveline from the Cougar would be a good fit in the then-new Ford Maverick. I went to a dealer and bought a new Maverick with the money I received from the insurance company, and gave both cars to Ernie so that he could work his magic.

When he finished, there was no indication that anything was different about the car; the stock hood even fit over the 4 bbl. carburetor and air cleaner. The headers were custom, of course, and in order to fit, the two middle pipes on each side had to cross over to the opposite side, giving even firing impulses into the collectors (true 180 degree headers). What made it even more of a sleeper was the sound; the even firing impulses made it sound just like a six cylinder engine. I had some fun with that car, a daily driver that could turn 12 flat @ 120 mph and pull the left front wheel off the ground on take-off. That was a really fast street car 50 years ago, still would be today I guess.

Side note: I had a set of the 427 Le Mans aluminum heads. They had smaller valves than the Medium Riser heads due to the room taken by the stellite steel valve seats. They also had a reputation for bowing head gaskets, so I didn’t use them. Probably worth a fortune today.

Remember this story when it first came out and now wonder, what happened to the Mustang once Joe got the car? Hagerty, please do a follow-up, if you can – would be great to see the Mustang all cleaned up!