The chips are down: Why the semiconductor shortage is hobbling the auto industry

Today’s cars are merely the boxes that the computers come in—a fact painfully illustrated earlier this year when numerous automakers shut down assembly lines due to a shortage of microprocessor chips. A modern vehicle uses dozens of chips to run everything from its engine controls to its stability and antilock braking systems to its in-car infotainment center. You can’t make a car without semiconductors, and presently, there simply aren’t enough of the right kind of chips to meet the current global appetite for electronic devices.

The problem is so acute that industry-analysis firm IHS Markit predicted that nearly 700,000 vehicles were not built in the first quarter of 2021 due to semiconductor shortages. Even as vehicle demand rebounded this past January from the pandemic, Ford was cutting shifts at two plants producing the F-150 pickup. GM and Stellantis, the parent of Chrysler, likewise idled plants in North America. As automakers scramble to shift their limited chip supply to hotter-selling and more profitable models, they’re facing a shortage that will not be solved soon. Though the auto supply chain in general has struggled to recover from COVID-19 chaos, the semiconductor end of it is being slammed by both short-term mistakes in demand forecasting and long-term industry trends.

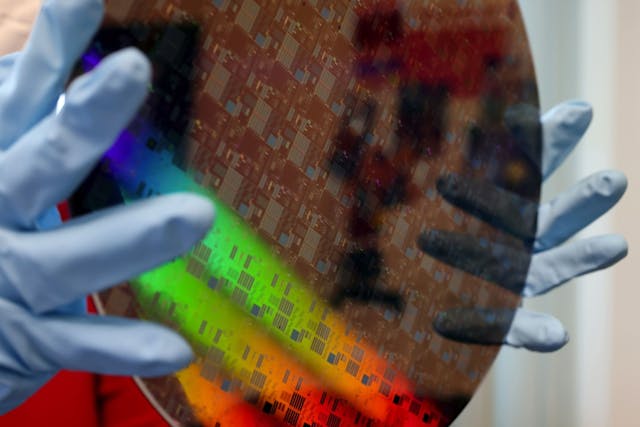

In mid-2020, the auto industry underestimated how quickly sales would rebound from the pandemic recession, causing chip capacity to go elsewhere—and especially to the flourishing work/school/play-at-home electronics market. Longer term, the auto sector is seen by the chip industry as having huge growth potential due to electrification and autonomy, but a production bottleneck afflicts the supply chain, especially for the types of leading-edge chips that automakers will need to make self-driving cars. These chips have tens of billions of transistors crammed on silicon wafers in circuits that are only 5 to 10 nanometers wide, which is the width of a few dozen atoms. The first 3-nanometer chips are expected in a few years. But while many companies around the world design chips, including Apple, Intel, Nvidia, and even Tesla, the actual manufacturing has been left to a shrinking club of fabrication facilities—“fabs” or “foundries,” in industry lingo—mainly in Taiwan and South Korea.

Pendulum swings between shortages and surpluses have characterized the semiconductor business since it started in the 1950s because the supply is, by nature, inflexible. It is considered the most expensive industry in the world to add capacity; while a new car factory might cost $1 billion–$2 billion, the price of a new fab starts at $15 billion and it can take five years to build one. There are single suppliers for some of the exotic tools and materials required to “grow” the salami-shaped ingots of silicon, slice the individual wafers, and etch them with their billions of circuits. The process can be extremely lengthy; some chips take months to make, with enormous cost penalties for mistakes. The toxic chemicals used—gallium nitride, sulfuric and hydrochloric acid, trichloroethylene—and the massive water and energy inputs mean it isn’t easy to locate a new fab. And the fabs have to be run flat-out to make a profit; they can’t afford to sit around with unused capacity.

Recently, U.S. producers of semiconductors begged the Biden administration to offer incentives to ramp up domestic chip-making capability, selling the subsidies as both economic and strategic security issues. But even if the U.S. does get behind the domestic chip industry (as governments in Asia have been doing for decades), the results won’t be seen for years. Meanwhile, chip makers are finding ways to stretch their capacity by eking out more production, in part by milking the older 200-millimeter-diameter wafer standard with fresh designs that can be made in existing fabs while more capacity for the newer 300-millimeter standard comes onstream later.

Chip making is an intensely complex business and now so concentrated in a few overseas suppliers that, like oil, its supply can twist with the political winds. But semiconductors are as vital to the modern car as wheels and tires, and without them, the auto plants won’t roll.