In praise of the Ford nine-inch

Chevy folks relish pointing out that their beloved small-block V-8 often powers hot rods from other makes. Yet Ford fans have a riposte: Crawl to the back of many of those rides and you’ll spot the Blue Oval’s nine-inch rear differential. For years, it has been preferred among customizers. But why?

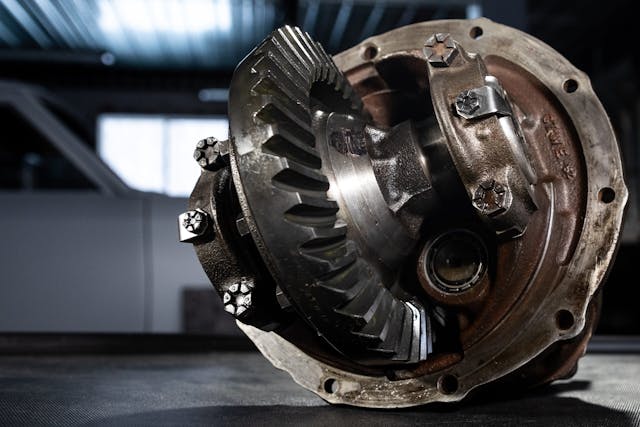

A rear differential, regardless of manufacturer, is a work of mechanical genius. Inside a bulbous metal housing known as the “pumpkin,” an intricate ballet of gears converts the driveshaft’s longitudinal rotation 90 degrees to drive the rear wheels. There are three main components: First, there’s a grooved-metal mushroom affixed to the driveshaft, called the pinion gear. It drives a ring gear, which looks like, well, a ring. In some drag-racers and rugged off-roaders, that ring essentially drives the wheels. But in most passenger vehicles, power is transferred via another set of gears that allow the wheels to run at different speeds—as happens when turning a corner—without binding. (Hence the word differential.)

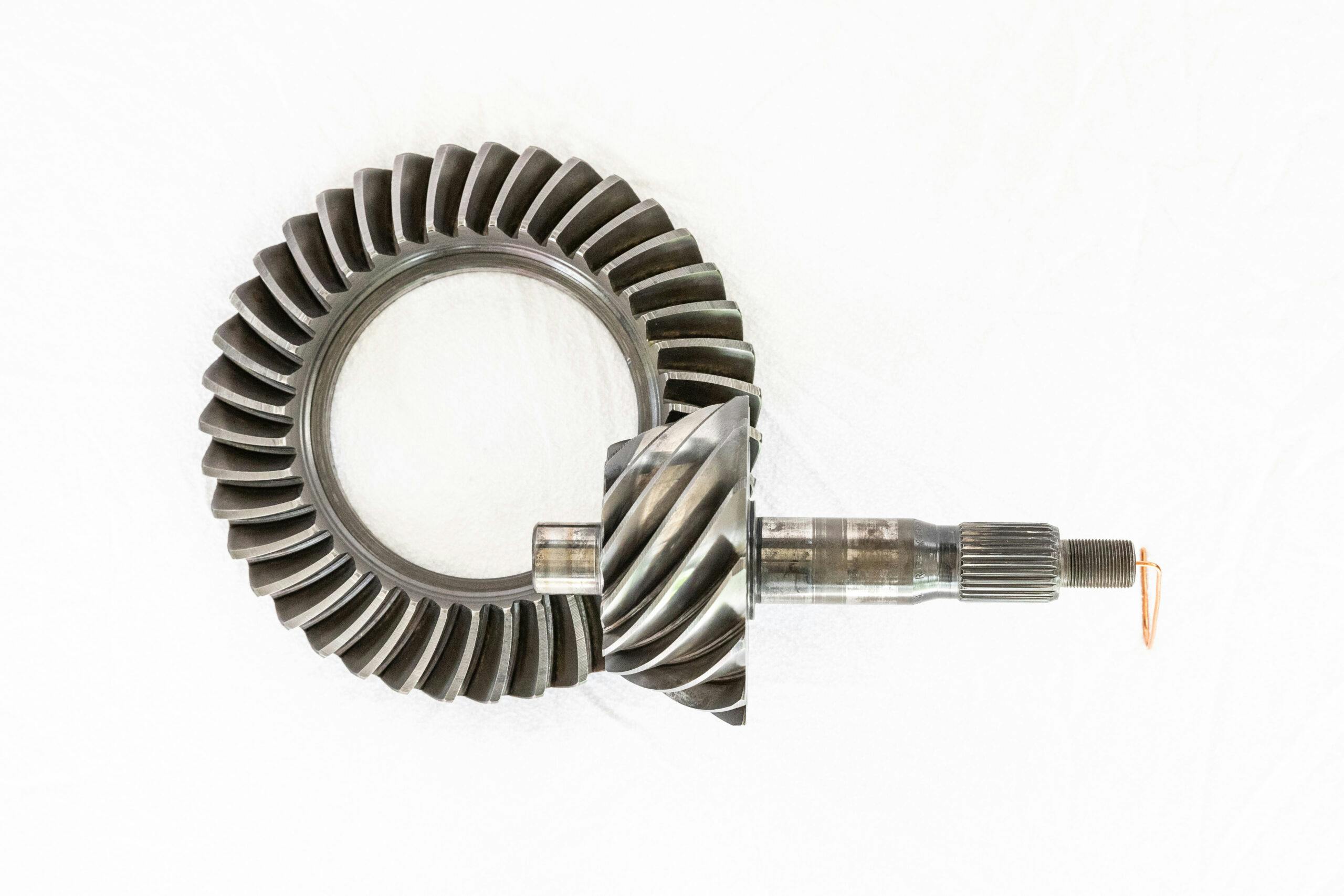

In early cars, the ring and pinion gears meshed at a 90-degree angle, with the pinion positioned at the ring’s 3 o’clock mark. However, in the 1920s, a Rochester, New York–based inventor figured out that angling the pinion’s teeth would allow more of them to engage with the ring at once, thus imparting more strength. This new setup (hypoid offset in engineering speak) also allowed the pinion to be mounted lower on the ring, meaning the entire car body could sit lower without a huge driveshaft hump inside. Middle-seat passengers everywhere can be thankful.

The Ford nine-inch, introduced in 1957, incorporated all that smart thinking but had distinct advantages. First, there’s the diameter of its ring gear at—you guessed it—nine inches. That’s larger and thus stronger than most contemporaries. Ford engineers increased the angle of the pinion’s teeth, as well. The diff was largely created at the behest of designers who were obsessed with lower floorpans, but the real benefit was quickly discovered by drag racers: The angle of the teeth imparted the strength to stand up to high-horsepower engines and fat rear tires.

Plus the unit was easy to work on. You access its guts by removing the driveshaft and 10 bolts, and the gearset drops out of the housing like a (heavy) printer cartridge. That means gear swaps can be done at a workbench rather than under the car. Some racers even carried multiple dropout diffs in their trailer for quick substitutions.

Ford phased out production of its nine-inch in the 1980s. Yet 30 years on, the rear end remains a favorite among enthusiasts for its strength, abundance, and convenience.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

One solid rear end. It is the only Ford part I have ever put in a GM vehicle.

In the late 60s . . . GM put Ford 3 Speed Top Loader Manuals in GTOs . . .

Still remember back in the day guys breaking their 10 bolts with an inline 6 . . . just by dumping the clutch!

You still have to remove the axles and the one great thing you missed was lash can be set on the bench rather than in the axle like the chevy 9 and 10 inch rears. There is also strength in the offset instead of the yoke sitting in the neck casting of other designs that are part of the entire axle casting.

Ford phased out production in the 1980s – but many new ones are still being built today…

Yes, indeed! Being built by many aftermarket companies. Non-Ford 9 inch rear ends may be coming close to the number of original ones built, by now. Love them and their aftermarket manufacturers, who will build a housing to fit just about anything for very reasonable money.!

Thanks, Cameron, for the simple-but-detailed explanation of this.

I had a decent theoretical knowledge of how differentials worked, but now understand them better.

Interestingly, the change of angle (that hypoid offset,) is also how VCRs manage to record more than the tape’s own width to the track. Plus, the heads rotate rapidly.

Great photography too.

Thank you! I had a great time putting the piece together. And my father enjoyed supplying—and cleaning—the 9″ for the shoot.

The biggest issue with a 9″ is noise if your vehicle doesn’t have mufflers louder than the whine that comes from them. Using factory original gears keeps the whine to a minimum but using any of the aftermarket sets can easily overpower your exhaust. Fortunately Gear FX is coming out with a modified 9″ carrier that uses 8.8 gear sets which are just as strong but don’t have the whine factor that a 9″ does.

Sounds like your gears are set up in correctly. I’ve run 9” rears in every vehicle I own. Little to no whine with any of them.

Have had several cars with 9″ rears . . . never heard a whine . . . perhaps it is your kids in the back seat!

I would change mechanics man . . .

Interesting to notice that there is no mention of the ’55 to ’64 Oldsmobile and Pontiac rear axle, which Ford obviously copied. The early dry lakes and drag racers would use those rear ends almost exclusively up into the late ’60’s until the nine inch became more common.

Hudson used the concept long before Oldsmobile, pre-war Hudsons had pumpkin rears . . . did Olds steal from them? The concept has been around far longer than suspect and a number of makes have used the concept . . .

And once again Ford did it Best ! ! !

J’ai eu quelque pick up ford (5) de 72-76-80-83-85, et toujours été obligé de les UP grader, parce que le transfert autoblockant ne fonctionnaient pas a merveille, obligé de remplacer l’huile a presque tous les 20k milles, et d’ajouter un additif de ford, pour qu’ils fonctionnent selon leurs specs, comparativement a un différentiel de Doge, et même GM, oui plus facile a travailler a cause du carrier arrière, mais pas suppérieur aux autres produits de c’est années là!!!!

Another strength is the extra bearing at the rear of the pinion gear. Most other pinion gears are cantilevered from the front bearings which can allow more deflection under heavy load.

I have one question. If the Ford 9″ is so good that Chev lovers install them in their muscle cars/ hot rods etc. why didn’t GM manufacture their own 9″ differential?

Easily the most popular rear end for drag racers. I’ve seen them on a few imports also.

Succinct explanation, yet another example of Chevy/Fordism, because the hypocycloidal curved gearset was first used by Packard throughout their range in 1926, a decade before the rest of the industry. It was designed in 1925 by the Gleason Gear Works, Rochester, NY. Because Packard shared the sorry, inevitable decline of all remaining independents in the 1950s, many today do not understand Packard was in their heyday world renowned for their technical prowess, cutting edge engineering aero, marine, land.

DP pointed out the biggest design difference between the 9″ and almost all other R&P diffs–the extra bearing on the nose of the pinion gear. This reduces the deflection of the R/P mesh AND reduces the side load on the pinion bearings and pinion housing.

To others’ comments about noisy 9″ diffs: I’ve set up a number of these, and if you pay attention, they will be quiet. After all, they were quiet when they came from the factory.

Another advantage consists of the carrier adjustment collars, which do not use shims, so you don’t need a collection of different thickness shims to set them up.

Good point, PK, but Packard’s ring gear deflection bearing was adjustable 85 years ago. And again, Packard introduced the hypoid rear axle a decade before the rest of the industry.

For the aging boys here gathered unable to grasp anything predating the Ford Mustang and Chevrolet Camaro, Packard was an enormous automaker in Detroit, Michigan, the biggest of the independents, the mostly widely held automotive stock after only General Motors (Ford Motor Company stock did not go public ’til January 17th, 1956), by far the leading choice of the world’s embassies through the ’40s, exported more automobiles the first half of the 20th Century than all other luxe automakers c o m b i n e d, building every configuration of internal combustion engine conceivable, the first domestic automobile to have a steering wheel, automatic spark advance, H-pattern gear shift, aluminum pistons (Walter Owen Bentley installed them in War I aero engines), air conditioning, produced the engines for our entire War II patrol torpedo boat and Army rescue boat fleets, as well as the two-stage, two-speed supercharged, liquid cooled Rolls-Royce Merlin V-12 used in the fastest Allied planes of the war, whose 1932-39 Twelve inspired Scuderia Ferrari president Count Felice Trossi and Enzo Ferrari’s nascent postwar V-12, owned up to 42% of all domestic fine car business (above $2,000 base FOB) through 1936.

We now return to breathless discussion of reskinned Ford Falcons and Chevrolet’s complete stylistic rip off of the 1962-64 Ferrari Lusso, already in progress.

You are the MAN!

Added to the above, the differentials in Packard’s senior (biggest-engined) models through 1950 used the further quality of an adjustable ring gear deflection bearing. The only other product to offer this in the day were the heavy duty GMC trucks, but they were not adjustable.

Underscoring Packard’s overbuilt quality was that in the 1960s, when the Cad-LaSalle transmissions in Don Garlits’ 1,000 hp Top Fuel blown Chrysler 426 rail dragsters blew apart—hence scatter shields — he switched to Packard’s j u n i o r version (that in their 245-ci six and smaller 282-ci “One Twenty” eight) of their 1939 R-6 transmission, and problem solved.