Long believed lost, this historic BMW 328 race car was hiding in plain sight

Across the digital world, most published content is bite-size, designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears. Pour your beverage of choice and join us for a Great Read. Want more? Have suggestions? Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: tips@hagerty.com

A photo from 1939 snapped just as the cars roll out from their angled parking positions at the start of the 24 Hours of Le Mans underscores what an intimate affair this storied French enduro used to be. The 4.5-liter V-12 Lagonda of Arthur Dobson and the Bugatti Type 57C of Jean-Pierre Wimille lead the charge down a pit straight barely wider than a country lane, while the Talbot-Lago T26 of Luigi Chinetti, who later forged an empire hawking Ferraris to Americans, gives chase. Picket fences and a hedge are all that separate the roaring machinery from the capped and woolen-coated crowd, a tragic lack of safety that wouldn’t be corrected until after the horrible crash of 1955.

Unseen in the photo, way off in the hazy clutter of the backmarkers, are three white cars from a small Munich firm that had entered the race for the first time, its six drivers having never been to Le Mans before. In those days, journalists writing about the Bayerische Motoren Werke put periods after every initial of its name, such that devoted readers of the motoring magazines and sports pages knew the firm as “B.M.W.” The company had been building automobiles for only 10 years and was better known for its motorcycles and aircraft engines, but BMW was intent on changing that.

Competing in the event’s 2.0-liter class were three factory-prepped BMW 328s that survived a crash- and failure-prone grind to finish first, second, and third in class—or fifth, seventh, and ninth overall. The little BMWs with their snarling inline-sixes vanquished much faster and more seasoned opponents, in part just by not breaking. This was the first chapter of an epic tale, a tale of 2002s knifing through the forests of the Nürburgring, of art cars and M1s and 1500-hp Brabham F1 engines and everything BMW has ever done on a track with an automobile.

It would be many years and a world war before that BMW would come into existence. This BMW was still small and humble, and somehow, miraculously, one of its white racing cars is sitting before us in a nondescript office park in Boca Raton, Florida, bubbling on its raspy idle. The car’s current owner, Stephen Bruno, curates a private menagerie of the rare and unusual, his tastes running particularly toward one-off, special-bodied Ferraris. However, he’s latched on to this obscure nugget of German racing history like a dog with a bone.

“I always look for the rarest of the rare,” he explained. On a rally once, he saw a BMW 328, the cycle-fendered Morgan-like roadster that was the company’s first production sports car. Fewer than 500 were built between 1936 and 1940, and Bruno wanted one. But, as usual, he wanted “the rarest of the rare.” Well, he got it, and the story of how he got it is pretty interesting.

Back in 1939, the cover art of the programme officielle for the 24 Hours of Le Mans depicted a racing driver hoisting up a pole a few flags of the world, including Old Glory and the red-and-black swastika ensign of the Third Reich—obviously some wishful sentiment on the eve of war about nations uniting in motorsport. Though it was BMW’s debut at Le Mans, the factory had been entering the 328 in lesser events since the car’s unveiling in 1936, including endurance races at the Nürburgring and at Montlhéry in France.

The 328 won its class in the blood-soaked 1938 Mille Miglia, during which a Lancia Aprilia plowed through a crowd of spectators in Bologna, and prospects were good for 1939, when BMW planned to enter every major sports car event on the European calendar. BMWs swept the season-opening British RAC Rally in April 1939, a fact that did not sit well with the Brits, who by then were developing a healthy grudge against all things German. The cars, including this one, also performed well in the Mille Miglia Africana, a 1000-kilometer dash held in the Italian colony of Libya after Italy banned road racing—briefly—following the ’38 tragedy.

Thus, even though the BMW team was crewed by six Le Mans rookies, they were primed for the race with tested equipment and a well-lubricated group. Post-Libya, the No. 27 car I’m sitting in—after I receive some instruction from Bruno’s chief technician—was sent to Le Mans to be helmed by a motorcycle racing jockey named Ralph Röese and his co-driver Paul Heinemann, the son of a building contractor who had started with BMW’s factory sports car team back in ’36.

As the seemingly endless daylight of the summer solstice neared, Europe’s sporting automakers headed for the ancient seat of France’s Plantagenet kings to race in the annual “double 12” on the narrow farm roads south of town. Favored at the start of the 16th running of Les 24 Heures du Mans was Jean Trémoulet of France, who had won the event the previous year in a Delahaye 135CS. However, three hours into the race, the 4.0-liter straight-six of Trémoulet’s Talbot-Lago SS roadster started bleeding out oil, causing chaos behind him as cars skidded and spun. The marshals tried to flag the Frenchman in, but he ignored them for several laps as he turned the 8-mile-long circuit into a skating rink.

At the 90-degree right-hander at Arnage, one of the race’s two female drivers, Anne-Cécile Rose-Itier (her co-driver, Suzanne Largeot, was the other) slid into the embankment and her Simca 8 rolled over. Jean Breillet, in another Simca, spun wildly and was thrown from the car 20 feet over a hedge. He miraculously survived with only bruises. Le Mans rookie André Bellecroix lost control of his Delahaye at 120 mph, hitting several trees and slamming into a house. He also survived, but with more serious injuries, and was taken away in an ambulance that had to circle the track among the race cars. When Trémoulet pitted at last, the crowd booed him long and hard.

The BMWs raced on, their white faces bearded with black gunk. Their only real competition in class was an Aston Martin 2-Litre Speed, a bigger version of Aston’s 1935 class winner. However, at the finish, the Touring-bodied BMW 328 coupe of His Serene Highness Prince Max von Schaumburg-Lippe and Fritz Hans Wenscher led the class, finishing fifth overall and just three laps behind a far more powerful Lagonda. Röese and Heinemann took second in class, seventh overall in the No. 27 car, and the No. 28 car of Willy Briem and Rudolf Scholtz wrapped up BMW’s sweep of the 2.0-liters, finishing ninth overall. The average speed of the race winners, Jean-Pierre Wimille and Pierre Veyron in a supercharged Bugatti Type 57C “Tank,” was 87 mph.

The Werke was riding high that summer of 1939. On the Friday before Le Mans, its motorcycle team had taken the top two spots in the Senior TT class at the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy, with winner Georg Meier’s supercharged 492cc BMW Type 225 RS hitting 132 mph on the island circuit’s notorious Sulby Straight. Meier was the first non-Briton to win the event since its founding in 1911, yet another cause for anti-Teutonic grumbling in the British press. No matter—BMW had made its mark and was rapidly ascending into the top tiers of European racing.

Three months later, Germany invaded Poland and the world fell into war. The problems of three little racing BMWs—to borrow the great line from Casablanca—didn’t amount to a hill of beans in that crazy world. As the bombs fell on Germany, two cars survived the conflagration with recorded stories, including the class-winning Touring-bodied coupe, No. 26, which is now in BMW’s museum in Munich. The No. 28 roadster also survived and was owned for a time by British racing journalist Denis Jenkinson, who famously navigated Stirling Moss to his 1955 Mille Miglia victory. Today it belongs to a private collector. However, the team’s middle car, the roadster numbered 27, disappeared for almost eight decades.

Well, actually, it didn’t. Somehow, in a manner that is as yet unknown, the No. 27 car made its way to America and into the hands of an owner whose tastes obviously ran toward the obscure. Few Yanks had ever heard of a BMW in the late 1940s or early ’50s, when the company was clawing its way out of the rubble making kitchen utensils and bicycles, and when this 328 is thought to have arrived stateside. The car passed from grandfather to grandson, undergoing a restoration in the 1990s that disguised it as “just another” roadgoing BMW 328.

By 2017, the car’s then-owner had become aware that it might be the missing ’39 Le Mans team car and Mille Miglia Africana veteran, rather than simply another BMW ex-competition car hiding under a handsome coat of silver paint over black disc wheels. He approached Daniel Rapley, a classic car dealer in Connecticut, about possibly selling the car. Rapley had a buyer, Stephen Bruno, if the car’s provenance could be authenticated. So as an initial investment, Bruno paid to fly Klaus Kutscher from BMW Group Classic in Munich over to inspect the car. He spent hours underneath it and with his head in the dark crevices. There he discovered that, besides the competition-spec rear axle and oversize fuel tank, the original Le Mans fuel-filler hole and special air vents were all there, covered over during the previous restoration. He pronounced the No. 27 car found, and Bruno unholstered his checkbook.

It was only the beginning of the spending, as Bruno wanted to return the car to its racing condition down to the single windshield, center driving light, and peculiar curlicue flourish adorning the 2 in its racing number. For that, he turned to D.L. George Historic Motorcars in Cochranville, Pennsylvania, which did the ground-up restoration. Fortunately, some of the competition parts that had been stripped off in the ’90s restoration had been packed away in attic boxes. The owner thought they were mods added to the car in the ’50s or ’60s but, thankfully, saved them. In fact, they were on the car when it raced at Le Mans in 1939.

One troubling aspect of the restoration that was was the headlight covers protecting the lenses from damage during the daylight hours of the race. The originals were gone, and no color photos of the car from that time are known to exist. So Bruno gambled that they were the same deep red as similar hard-shell covers used in the day by Alfa Romeo and other teams. “We just went with what we thought was correct, but we pontificated for months,” he said.

Because literally everything was politicized in prewar Germany, BMW’s racing cars bore the NSKK logo of the Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps, or National Socialist Motor Corps. It was basically the Third Reich’s equivalent of the Auto Club, charged with educating new legions of drivers for industry and the Wehrmacht and supporting competition events. The logo, which was on the cars in Libya, depicts the Third Reich eagle underneath a banner that reads “N.S.K.K.” and clutching a laurel wreath with a swastika in the middle. Mindful of modern sensitivities toward the image, Bruno exercised one bit of creative license and left the logos off the doors.

Otherwise, the 328 is just as Ralph Röese and Paul Heinemann drove it, or as near as Bruno could make it given the limited amount of documentation and archival photos available. At first glance, it’s easy to mistake it for any number of British roadsters from the 1930s, except that the dual-kidney grille is a giveaway that the car is a proud son of Munich.

The rear-hinge doors swing just wide enough for people of average girth to slide through. Sitting in the car is akin to sitting in an MG TC or other roadsters of the era, in that the large black steering wheel with linguine-thin spokes is up close and always brushing your lap, and the close-coupled foot pedals seem to be made for people who drove in nothing but stockings.

Giant, white, clockwise-rotating gauges read out the speed (max 180 kph) and engine revs (max 5000 rpm), while a brace of uniformly small instruments report the fuel state and health of the engine’s oil and cooling systems. One of the handles on the dash activates the slide-out trafficators in the body, which return to the stowed position with a satisfying thunk. You turn a small key marked with Bosch’s familiar armature-in-a-circle logo, then push the starter button marked with the same logo, and the inline-six lights right off with a raspy syncopated snore that instantly defines the car as something other than a clattering British side-valver.

BMW had evolved from its start in 1917 as an aircraft engine maker to motorcycles in 1923 and then cars in 1929 with the acquisition of Dixi, a company that was burning through cash while building British Austin Sevens under license in Eisenach in central Germany. That was just in time for the national economy to collapse in sync with the global Depression, which helped launch fascism in Germany. Considering the titanic obstacles that any carmaker needed to overcome in the 1930s, it’s something of a miracle that the 328 was ever produced, much less produced with such a dramatic increase in sophistication over the company’s previous cars.

Although a car company today employs thousands of engineers, back then, the 328’s existence was largely down to the work and persistence of two men, Rudolf Schleicher and Fritz Fiedler. The former had come to BMW in 1922 to help launch motorcycle manufacturing in Munich. In 1927, he left for a job at Horch, where he met Fiedler. BMW, having entered the car business and wanting to take a big technical leap from the Dixi, lured Schleicher back to Munich in 1932. He persuaded his friend Fiedler to go with him.

The small company didn’t have much in the way of resources, just some guys standing at drafting tables day after day over the better part of a year, sketching out their idea of a lightweight two-seater with a tubular steel chassis, flowing contemporary lines, and a novel overhead-valve inline-six. The suspension hewed to late-1930s convention with a single transverse leaf spring up front supporting independent control arms, and a solid rear axle on semi-elliptical leaf springs. Fiedler handled the frame and body development, while Schleicher, along with his colleague Rudolf Flemming, fleshed out the new engine.

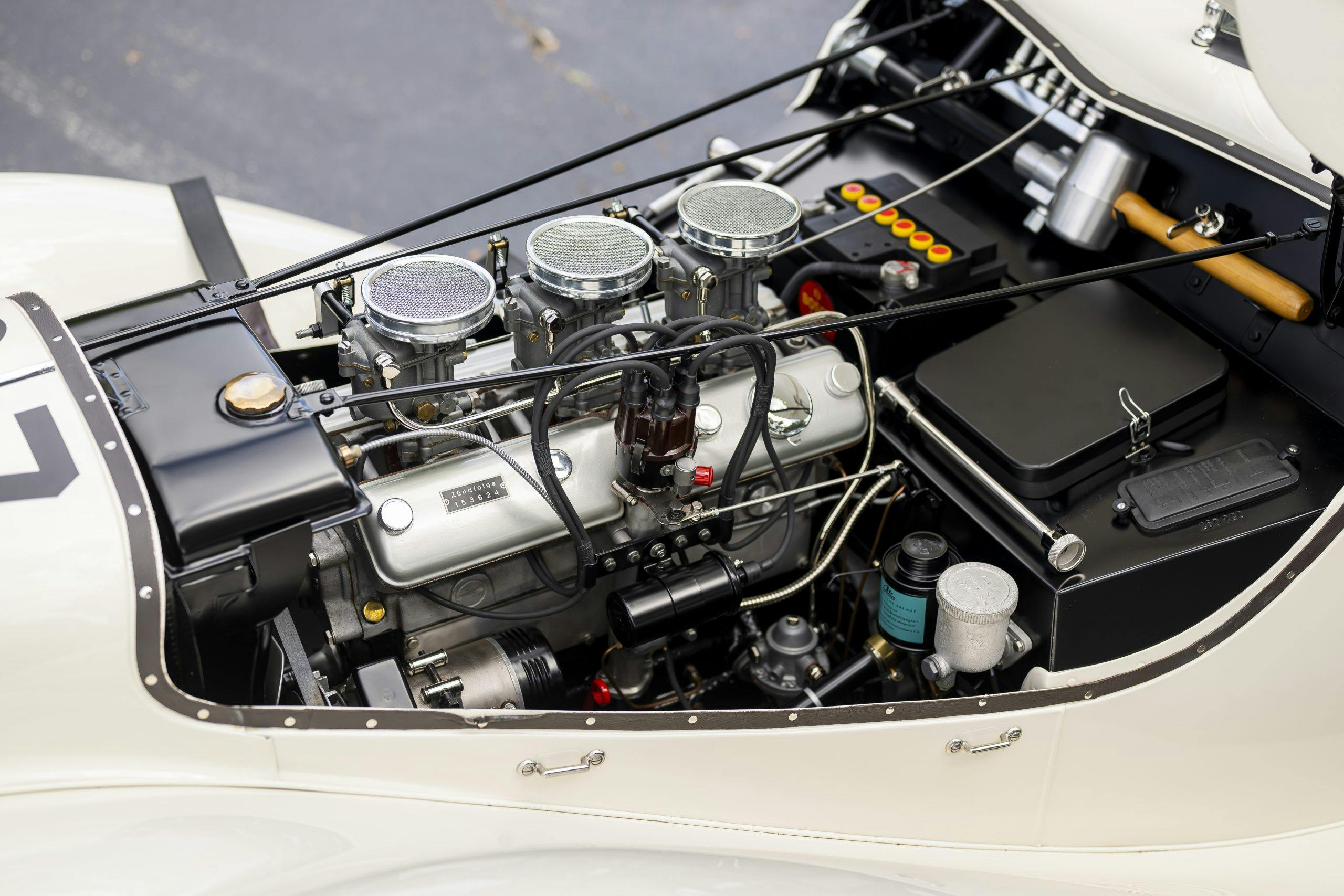

The 1971-cc six used the iron block from an earlier production sedan, but with a new aluminum cylinder head to produce the higher output befitting a sports car. It featured semi-hemispherical combustion chambers that splayed the valves at a wide angle and placed the plug in the center for better breathing and combustion. The arrangement demanded that the engine have either two separate camshafts or some novel way of actuating both the intake and exhaust valves from one camshaft. Overhead cams were rejected because it would require the development of an entirely new engine, something BMW couldn’t afford. Since the whole project was being done on a shoestring, the team was stuck with a single-camshaft block from the previous BMW 326 sedan. Thus, the solution was to incorporate three sets of pushrods: One conventional vertical set moved the intake-valve rocker arms; another parallel set moved bell cranks on the rocker shaft in the head; and a third set of short, horizontal pushrods reached across the head from the bell cranks to move the exhaust-valve rockers.

Three center-mounted Solex type 30 downdraft carburetors do the breathing as well as make the engine look pretty. With a 7.5:1 compression ratio, brake horsepower was listed in the catalog as 80 at 4500 rpm, but competition models were almost certainly above 90 horsepower, with the Le Mans cars thought to make in the neighborhood of 135 horsepower. Which is one reason the early racing cars were fragile; the running gear lifted straight from the sedans wasn’t up to handling the power of the 328’s engine. From its first race in June 1936, the 328 underwent continuous development as bits broke and were reinforced.

Luckily there’s some decent driving within blocks of Bruno’s office, and I was able to run the car’s Hurth four-speed through its gears. The clutch is light and the takeup exceptionally smooth. The car immediately makes friends and is easy to drive. A conventional shift pattern with reverse left and up, the selector feels direct, with an obvious and satisfying engagement. The car was fresh out of the restoration shop, and some more miles on the gearbox would probably loosen it up. Indeed, the whole car feels a bit like a new saddle not yet worn in. Maybe, as with many valuable classics, it never will be. But you can easily picture yourself getting comfortable enough with this benign and predictable machine to make fast midnight runs through Maison Blanche or down the Mulsanne, living life to the fullest in the last happy moments before the abyss.

Neither Röese nor Heinemann ever raced at Le Mans again, and their nation burned to ashes in a war that consumed many of the people and vehicles they raced against that June weekend in the French countryside. Jean Trémoulet, whom the crowd jeered so viciously, died in a motorcycle accident in 1944, it was said while on a mission for the French Resistance. BMW’s Munich factories were bombed to dust, its operations in Eisenach seized by the Soviets. The company was prohibited by the occupying Allies from making cars until 1951, though the British Bristol Aeroplane Company recognized the value of BMW’s engineering and launched itself into the auto industry in 1947 with cars and engines pilfered from BMW designs, replete with the split-kidney grille.

As we all know, BMW was irrepressible, and it emerged to flower as an automaker and to race again at Le Mans—finally winning it all in 1999 with its V12 LMR prototype. That was a feat for sure, but this charming little roadster managed to pull off an even greater triumph: It outraced the clock and, thanks to its various caretakers (some known, some unknown), it survived the past 83 years to bear witness to a moment when a world was just about to end but a really good story was just getting started.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Now there is a car to drool over – especially for those of us who enjoy the ‘rare’. Great article and very interesting photos. Thanks for this story!

The first time I ever saw one of these was in a sixties war movie, being driven by a German U-boat commander on leave. In my eyes it’s one of the most beautiful prewar roadsters ever built, sleek ,small and fast.

I love these kind of stories. Hagerty has filled the niche once occupied by Road and Track and Automobile Quarterly.

A couple years ago, I answered a Craigslist ad for someone selling his collection of Automobile Quarterly magazines. He first subscribed in 1969 with his last issues arriving in 2006. That’s 151 issues. He was asking $5.00 per issue but I felt that was a bit steep. A month or so later he relisted the collection. I told him that I was not a collector but that I wanted to read all of them. I offered him $2 per issue. He accepted because he was glad someone was going to actually read them.

After I read the first couple issues, I liked them so much that I decided to acquire all of the issues, which I did. I started over at reading the first issue from 1962 and am currently reading issues from 1993. I still have nearly 30 years of issues left to read, so I am a little over halfway through the collection. I was a history major in college and have always enjoyed reading the history of various cars I have owned. The Automobile Quarterly issues have made for very enjoyable reading where I have discovered things I never knew existed in automotive history. I am so glad I bought those initial issues.

Interesting to read about the rocker arm actuation. In the ’80’s, Arias used the same solution to make their 8.2 litre Hemi-Chevy cylinder heads work with a production located camshaft. The design was later updated to accept a much longer exhaust rocker arm which eliminated the need for the horizontal pushrod.

What a neat story about a winning race car!

Very interesting story. I had not known about BMW’s pre-WW2 history.

Wouldn’t the BMW 315/1 roadster, produced from 1934-1936, have been the company’s first production sports car?

The restoration is amazing. Everything looks new. After amateur restoring/building cars, I now realize how much work that is (might be, I’ve never done it ha). Impressive.