The scale R/C world shrinks everything about off-roading—except the passion

Mike Lohmann is worried about his driveshaft. It’s nine in the morning, but the Florida sun is already marching across the sky, turning the air into a sweat-inducing roux. As Lohmann tells it, last-minute modifications to his 1985 Toyota Hilux had unintended consequences. “New front leaf shackles,” he says. “Bit more travel, but the added droop must have adjusted the geometry a bit, pulling the front axle forward.” Lohmann is the leader of our convoy, which scans like a Pure Moods album for classic 4x4s: There’s a Toyota FJ60 Land Cruiser, two more Hilux pickups, a K5 Chevy Blazer, numerous Jeeps, even an International Scout.

Lohmann positions his front tires to maximize purchase over a limestone boulder blocking the trail, then eases into the throttle. The crawler takes a lean and begins pirouetting over the obstacle, only to high-center on its frame. All four wheels spin. A small pop emanates from the front end.

“Ope,” Lohmann chuckles. “RIP front driveshaft.” He reaches down and scoops up the Toyota with a single hand, then ambles off to execute a fix.

Trailside repairs aren’t that bad when your rig fits in a backpack.

Welcome to the Ultimate Scale Truck Expo, USTE for short. For three days each February, a retired limestone quarry and a few cow pastures near Williston, Florida play host to nearly a thousand people, all of whom have gathered in celebration of radio-controlled “scale” rock crawling. Now in its sixth year, the show pulls around 40 vendors, representation from a dozen countries, and several thousand miniature versions of history’s best off-road vehicles.

The scale-crawling origin story resembles that of 1950s hot-rodding. Four-wheel-drive R/Cs have been around since the 1980s, but the scale movement owes much of its growth to a forum launched around 20 years ago. R/C hobbyist and life-size—what the community calls “1:1”—crawling fanatic Jason Hansel founded RCCrawler.com for those who preferred slow and steady dirt driving to circuit racing.

Dean Hsiao, a long-time RC hobbyist, was one of the first to chase scale realism in earnest. A mechanic by trade, he wanted to create a miniature version of the 1:1 1983 Toyota pickup that he crawled with on the weekends. He took a 1:10-scale Tamiya Bruiser R/C body produced in the 1980s, modified the kit’s ladder frame to accept 1:18-scale axles from an early 2000s Tamiya TLT kit, then cut down tires to fit and ditched the Bruiser’s three-speed gearbox for a single-speed unit.

Much like the first chopped ’32 Ford, Hsiao’s build was a watershed moment. His work quickly became known as the Chino Crawler, after his forum username, Chino63.

Lohmann was on the forum in those early days. “I see this thing,” he says, “and I’m like, ‘This is the most realistic R/C truck I’ve ever seen and it’s awesome.’ I wanted to build one.”

He wasn’t alone. In the months that followed, dozens of other forum members hatched similar builds, all proudly referred to as Chino Clones. (Lohmann built his own Chino clone, but he also eventually purchased the original Chino crawler from Hsiao.)

Those early days of scale building were mostly home-grown efforts. Naysayers abounded. “When [scale building] started,” Lohmann says, “a lot of people just thought it was a fad.” Manufacturers showed a similar skepticism at first, forcing the scale guys to get creative. As demand for scale parts grew, people in the scene began offering their day-job skills—machining, metalwork, welding, vinyl wrapping and more—and spare time to help conjure limited-run builds. This came to mean everything from frames and cages to hubs and entire vehicle bodies.

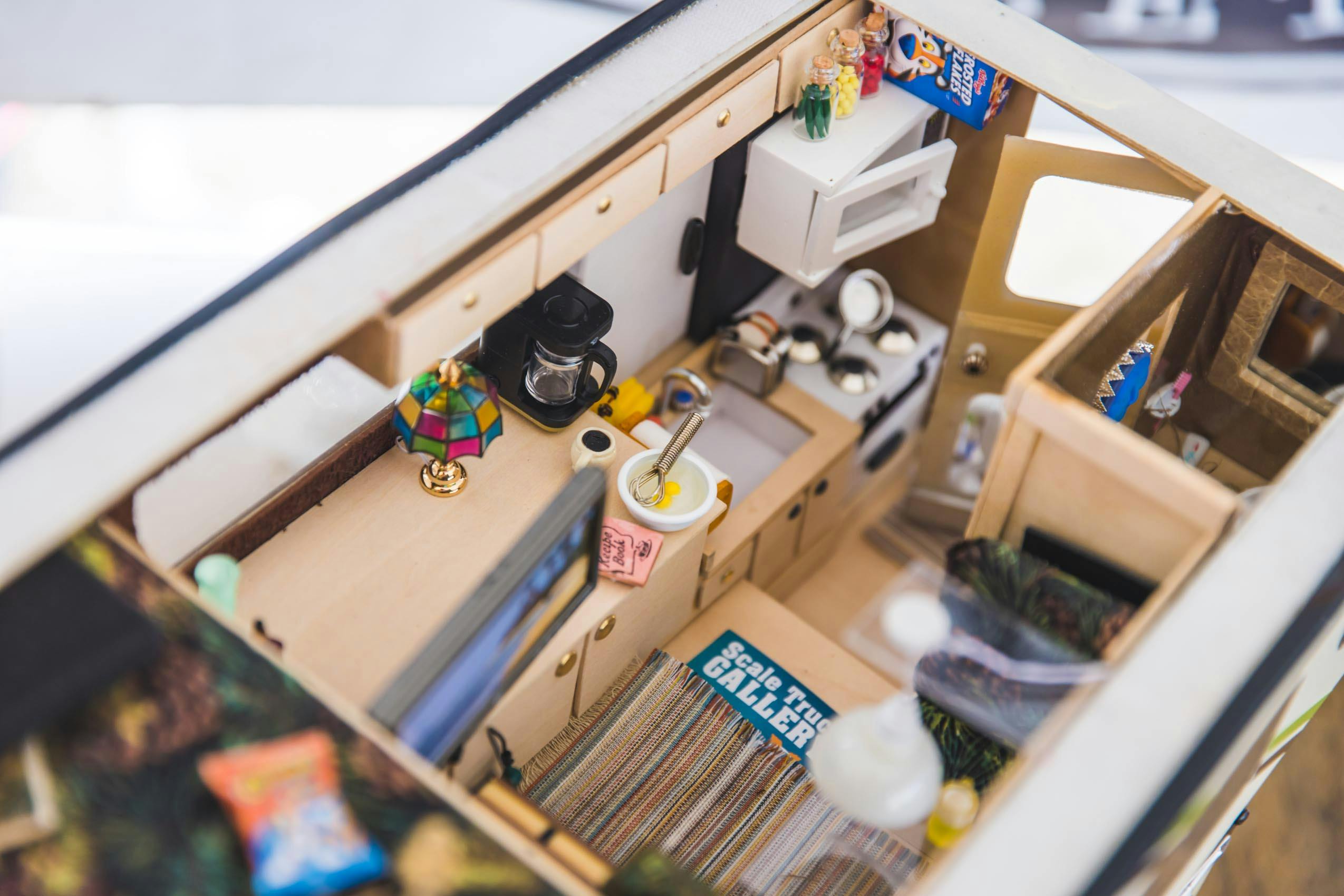

One-upmanship started early. Thin plastic bodies were peeled open to accept detailed interiors. Action figures were posed behind steering wheels. Toy dogs from Tractor Supply Co. became dutiful co-pilots. Auxiliary air tanks were fashioned from BB-gun CO2 canisters, then fitted with scale hoses made from, in some cases, a citronella bracelet wearing ballpoint-pen springs on either end. (Yes, really.)

The modeling side of things got longtime friends and R/C enthusiasts Rob Matthews and Cory Verne thinking about an event. In late 2015, the two men noticed that, although the scene held plenty of events dedicated to competition and recreation, no gathering championed scale craftsmanship.

Matthews is quick to credit Verne for the idea’s inception. “In those early days, none of this went fast because neither of us had a friggin’ clue what we were doing.” Verne’s day job as a first responder eventually led him to step into a supporting role a few months prior to the first event, which took place in 2017. Matthews was left at the helm, where he remains today.

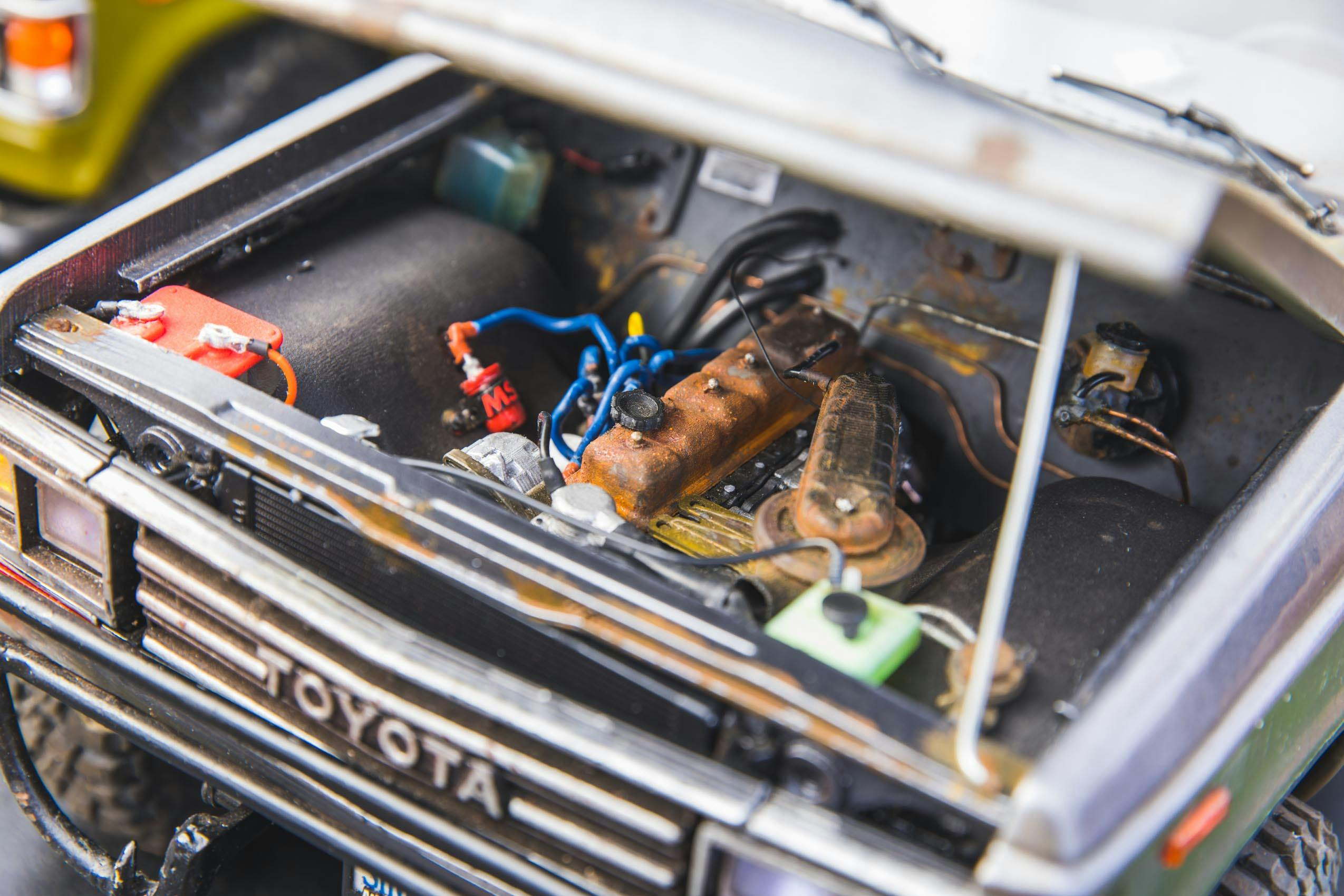

USTE’s goal is simple but compelling: connect manufacturers with those who spend hundreds of hours fretting a build’s lifelike details. The event features classes that teach skills like weathering, scale photography, styrene modeling, and more. Top builders compete in judged categories for awards like Best Detail, Best Accessory, Best Engine Bay, and the prime achievement, Best in Show.

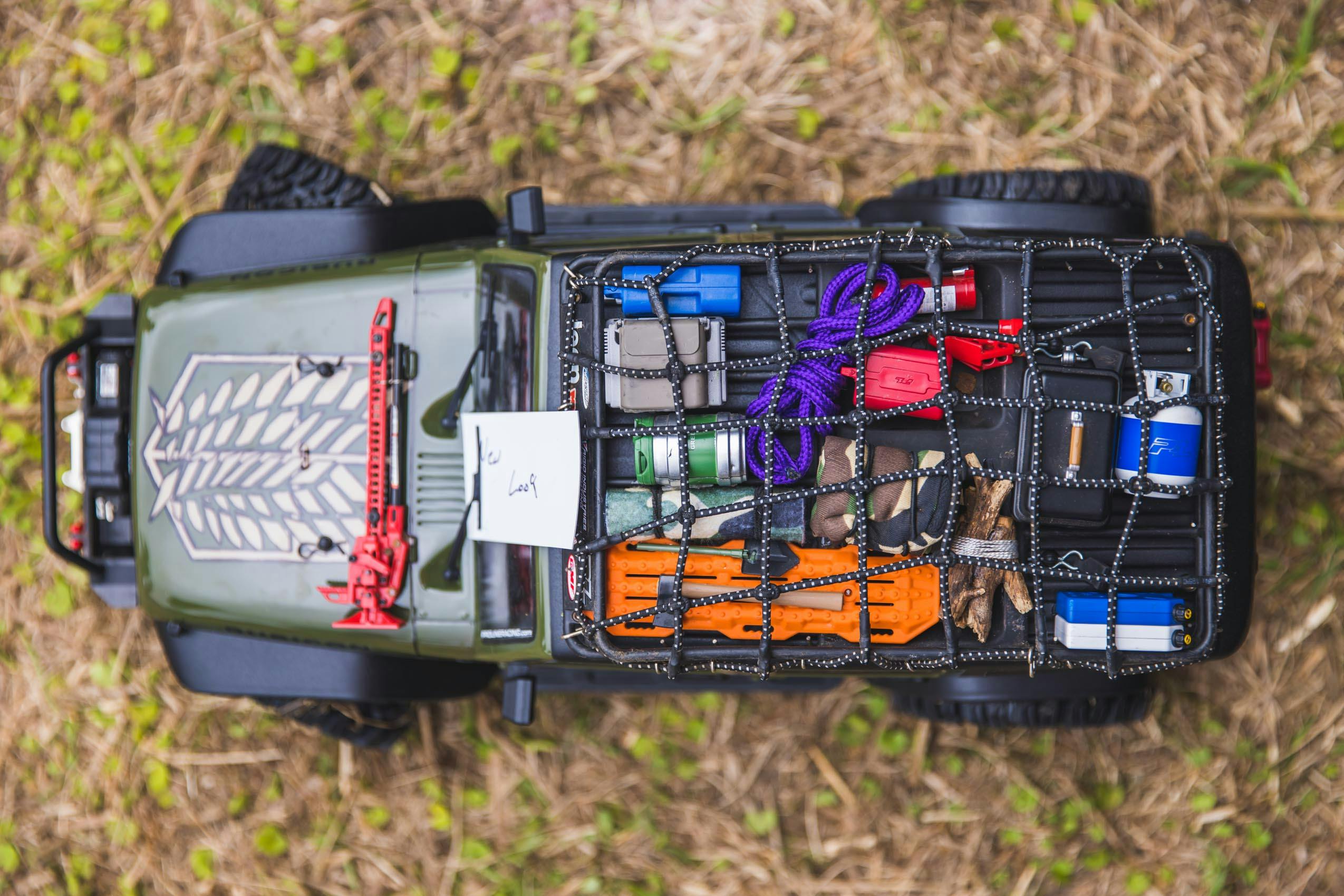

Several hundred builds were entered for judging this year. Top honors went to none other than Lohmann, whose pickup, christened Too Rad, blended exquisite paintwork with a cargo bed that could lift and tilt sideways under servo power, just like the flashy show trucks that prowled Miami beaches in the 1980s. Too Rad was the runaway favorite but also one of Lohmann’s most impressive builds—which is saying something, given that his personal R/C fleet numbers north of 100 vehicles.

While the builds are a draw for many, USTE is far from static. Matthews and his team spend months prior to each event carving more than 13 miles of crawling trails through the woods around the main show field. This means rock gardens, a mud pit, hill climbs, hundreds of individual and flag-marked obstacles. There are massive suspension bridges, the longest of which span more than 90 feet. Scale buildings and props are scattered throughout each course to enhance photo ops and add atmosphere.

The whole place buzzes with the same feeling that hangs over the best and most egalitarian car shows. Thousands of R/Cs zip about the showgrounds and pines, builders in tow and dodging cow pies. Families make a weekend of it, kids spotting for parents and vice versa. Vendors prop up tents, cheerfully answering questions about builds and new tech.

Although early builds like the Chino Crawler made do with piecemeal mechanicals, the contemporary scene bursts with manufacturers churning out crawling-specific versions of every component imaginable. Tiremakers employ brand-specific tread patterns and proprietary rubber compounds that deform to terrain like 1:1 rubber. Scale ladder frames house electric motors, transmissions, and transfer cases. The most common suspension setups employ solid axles front and rear, usually with three or four locating links, though some models sport independent front suspension, often if the 1:1 machines they replicate feature a similar setup. Depending on complexity and cost, differentials are either open, locked, or, in some newer models, selectably lockable.

The radio-control hardware is unique in places but would nonetheless be familiar to anyone with time in the hobby. Steering and other modular functions are handled by servos—small radio-controlled motor-gearbox assemblies that provide calibrated, steppable movement. Power comes primarily from lithium-polymer batteries, with most packs outputting between 1000 and 3500 milliamp-hours. Drive comes from compact electric motors no larger than a shot glass. Crawling motors have more wire wrappings than most R/C drive units—“turns,” in the parlance—so they rotate slower and offer more torque. (Context: Drag-race R/Cs often use 12-turn motors; crawlers can employ 35 turns or higher.)

The R/C components not found on 1:1 rigs—batteries, receivers, and so on—all have to go somewhere, and scale appearance means tucking them out of sight, which means ingenuity. Some builders opt for smaller battery packs, which are easier to hide, while others toss a scale “toolbox” in their truck’s bed to add concealed volume. Work like that affects the cohesion of the entire package and helps separate premier work. Go far enough with the hiding and detail, your build will be referred to as a “dollhouse truck,” the hobby’s highest compliment.

For realism and capability in equal measure, you can’t do much better than a call to GCM Racing. The Ontario firm specializes in CNC-milled, billet-aluminum drive and chassis components, all designed to replace or supplement the plastic mechanicals in most modern R/C kits. Touches like married transfer cases and front drive shafts that descend on the proper side of an “engine” for a specific marque (left for a Jeep, right for a Toyota) are common.

“We want the trucks to look as realistic as possible,” explains Chris Robinson, GCM’s founder. “We want to be able to say to a guy who’s building a ’79 Bronco, you need a Ford axle with a Dana 44 cover on the front, it needs a driver’s-side drop for North America, it needs a driver’s-side-drop transfer case, and we have all that stuff. You don’t have to compromise the look of [your build].”

At USTE, GCM loaned me one of its most famous rigs—a 1989 Jeep Comanche Sport Truck, built on the company’s most popular chassis, the CMAX. “Neat to heck,” Robinson said. “Straight from Ohio. Except for the rims—I put new ones on it, so they’re a bit too shiny. Feel free to dust them up.” The Comanche looked like a transplant from a Pennsylvania Christmas-tree farm, from the carefully weathered bodywork to the set of 3-D-printed Crocs in the bed. It was somehow just as endearing as a full-size Comanche, a cheery little snapshot into a modest agricultural life from a different time. I wanted to hug it.

Brent Gila, the volunteer behind USTE’s massive suspension bridges, invited me to join him at the trail hillclimb the night before the event kicked off. By day, Gila is the director of a nanofacility at The University of Florida in nearby Gainsville, but he spends nights and weekends futzing with scale R/Cs. His Wrangler led the way up the trail, the Comanche close behind.

Small doesn’t mean simple, and scale rigs have a full-size learning curve. The throttle was meted by a trigger on the Jeep’s pistol-shaped transmitter and took a delicate touch—if I squeezed my finger a millimeter too far, the Comanche would go rocketing off the hill. Ditto for steering inputs. Some obstacles required me to change location, and the resulting perspective shift proved disorienting in early going.

Still, the process was fun and rewarding. You start thinking like an off-roader immediately, tracing the same decision tree as you would in a 1:1 truck: Place your front tire carefully. Watch the approach angle. Set the inside rear up to pivot on the tip of a rock over here, clearing the way for a clean departure over there. Within minutes, I’m caught up in a miniature world, ambling past a scale horse farm, then a fire lookout, laser-focused on placing the Jeep for a tight switchback ahead. Landing a difficult maneuver brings fist pumps and laughter. USTE people make the same noises and gestures you’d see at Hell’s Gate in Moab, they’re just walking over a pile of dirt in a Florida field.

In moments between obstacles, Gila and I discussed how he found R/C. “I used to own a four-wheel-drive, and I’d go hunting, fishing, play in the mud. But then I’d spend all day Sunday fixing it to drive to work on Monday.” Constant upkeep on his ’77 Chevy stepside grew tiring, he said, so much that he and the truck eventually parted ways. “When this breaks, it goes in the trunk, I take it home, and it sits on the shelf until I get time to fix it. I don’t have to drive this to work.”

The final challenge of this year’s USTE hillclimb was a zipline platform that, once crested, whisked your rig back down to the beginning of the trail. As if to prove his point, Gila misjudged the speed of his approach. His Jeep Wrangler careened off the platform’s edge, falling end-over-end the entire length of the hill before coming to rest on its cage. He laughed, scrambling down the hill to scoop up the crawler. Damage was limited to a bent cage and a broken body connector, plus a few interior details strewn in the dirt.

He laughs. “Guess I’m firing up the 3-D printer tonight.”

The next day, I followed Lohmann and a few others out for a morning run, our cavalcade of tiny trucks scrambling over roots and off-camber switchbacks. The Comanche’s smaller tires were a boon to realism, but I quickly grew jealous of the larger rubber and longer-travel suspension on other builds. The moment was instructive, the same discovery of theory and application I’ve had exploring unpaved Michigan in my 1998 Montero—except here, I’m refining the same skills in a truck that costs less than a set of the Mitsubishi’s tires.

Our trail run intersects with a handful of others. I meet Gary Yokley, who’s quick to make it clear that he’s only involved in RCs for the driving—his grandson Brett Levan handles the construction, he says. (“I’m not intelligent enough to do that,” Yokley jokes.) Brett’s white and red Hilux is a riff on the wonderfully preserved, 1:1 1986 Toyota Pickup he brought to the show. The Hilux’s bed holds a scale dirt bike, a nod to one of Levan’s hobbies. Yokley’s Land Rover Defender is just as impressive—less weathered, but tidy and simple, like a lot of full-size Landies.

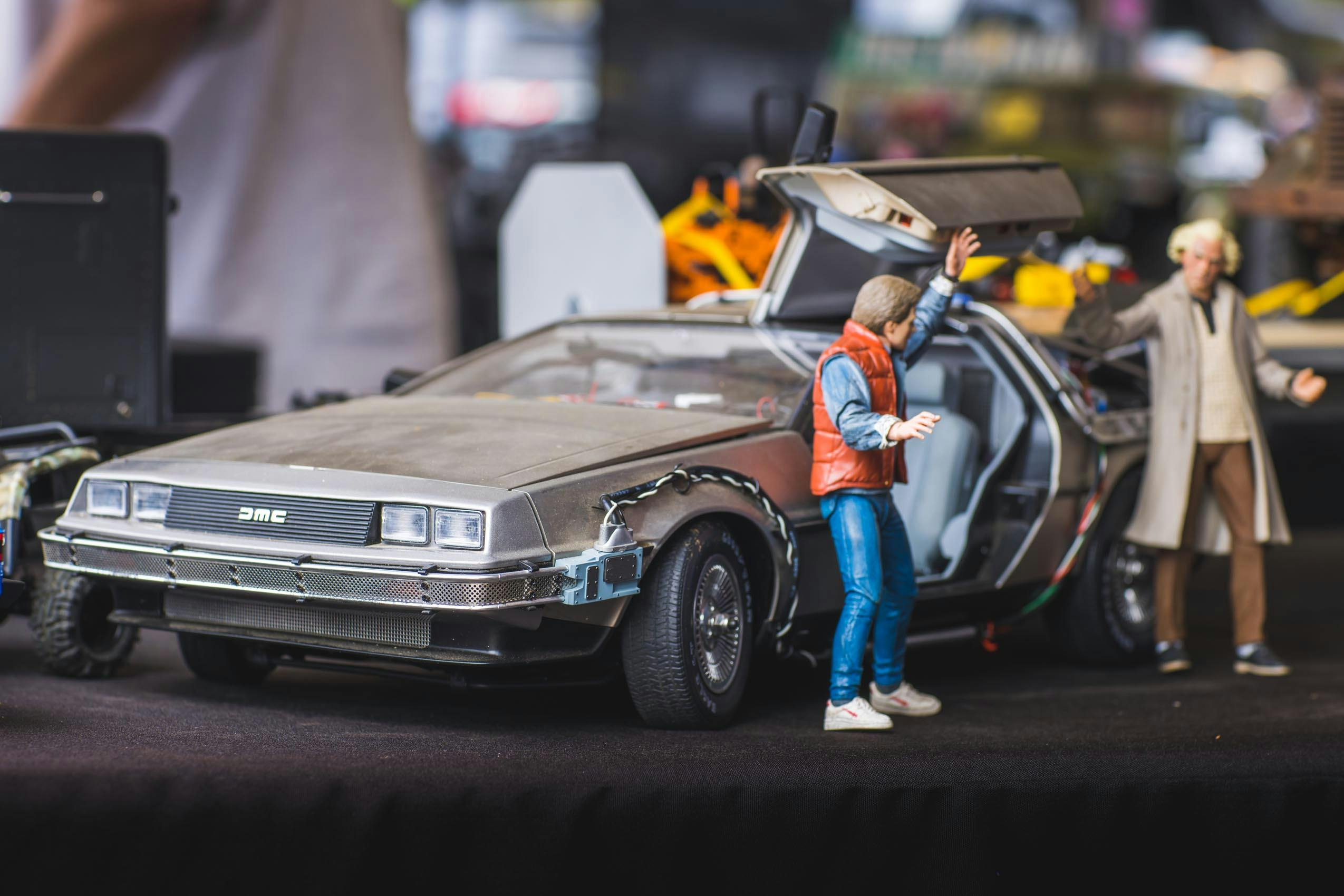

While countless builds are inspired by roadgoing rigs, many USTE trucks are simply vessels for enjoyment, basic stock kits slapped together and pointed at the nearest obstacle. The dichotomy recalled the varying levels of commitment seen at full-scale car shows. But where 1:1 shows often hold unfortunate gatekeeping and ranking, USTE seemed absent condescension. Every interaction I caught a piece of carried an undercurrent of positivity and support. Veteran builders fist-bumped ten-year-olds chasing new Broncos through the pasture. High-end manufacturers patiently walked through the steps of a basic servo upgrade with a teenager about to hack apart her first Wrangler. A respected Japanese specialist enthusiastically pulled the body from his 1:10 Land Cruiser for an awestruck bystander, then explained how he wired a tiny TV in the trunk to play Back to The Future at the press of a button.

The common thread is accessibility. A 16-year-old can scoop a ready-made crawler for a few hundred bucks, and it’s possible to create an advanced build for less than $2000. A scale rig can be pulled apart at the dinner table, then run in your backyard on any given Tuesday. Scale R/C’s affordability is also a boon for many folks who would otherwise find the full-size car hobby cost-prohibitive. Matthews reckons that less than a quarter of those at USTE have any 1:1 off-roading experience at all, a claim backed up by my casual chats with attendees.

That accessibility plays out another way, too. Vintage 4x4s have recently become one of the hottest things going in collector vehicles. With real Land Cruisers, Blazers, and Rovers rapidly appreciating, scale crawling offers young enthusiasts a simulacrum of the 1:1 machinery that their parents enjoyed on the cheap.

Here’s GCM’s Chris Robinson again, who put it perfectly:

“You’re a 16-year-old kid on your grandpa’s farm, and he’s driving a K20 around. It’s full of hay and guns, and that’s what you’ve seen for most of your high-school life. And then you get out of college, and at Christmas, you go to visit the farm and there’s the truck, rotting to death. Next thing you know, you’re looking up pictures of K20s on the internet, and what shows up? Probably a picture of a really awesome R/C truck. And so you find this [scale] K20, or Blazer, or old Bronco or whatever, that you can just go and buy, right now, for under a thousand bucks.”

Maybe that kid remains enamored with the K20 and can one day spring for the real thing. Maybe through R/C he stumbles onto a different 4×4 model, and that becomes the dream ride. The possibilities are both attainable and endless. Want to burn a Saturday crawling half an acre of woods with your friends? Want to turn wrenches but short on floorspace and budget? Scale R/C is a conduit to the broader automotive hobby worth celebrating, the same as driving video games or Hot Wheels. USTE boiled over with a familiar energy, the same fuel that compels us to wake up before dawn on Saturdays for cars and coffee, that helps rationalize an afternoon drive instead of heading out to mow the lawn.

Though the subject matter is small, the passion is anything but.