Rolling Evidence: Forensic Files reveals how cars end up at crime scenes

While binge-watching old episodes of the TV show Forensic Files, I began to notice that a lot of crimes involve cars. People were hit by them, kidnapped in them, and murdered inside them. Cars were stolen, wrecked, and set on fire. After searching a suspect’s house, the next place police always looked was their car.

“In the forensic sphere, cars are a major source of evidence,” explained Chris Palenik, a forensic microscopist (microscope expert) at Microtrace, LLC. “Whether cars provide the evidence, through losing paint or losing fibers to a suspect or victim; or the opposite, where the car picks up evidence because something hit against it, or a gun was fired in it, or hairs were lost in it.”

Chris and his father, Skip Palenik, have worked on thousands of criminal, civil, and industrial cases—many involving vehicles. Of course, not every car clue is microscopic; some are personal.

“I watch true crime because it teaches lessons about human nature,” Rebecca Reisner, true crime blogger and author of Forensic Files Now, told me. “But I’ve really come to appreciate forensic evidence, because people’s memories are a mix of things . . . and you can absolutely testify that someone was there and you could be totally wrong.”

The numbers game

Solving crime often boils down to “who?” “when?” and “where?” and license plates are the fastest way to identify a car and its owner. In one Forensic Files episode, a team of serial bank robbers was finally caught because a savvy witness wrote down their license plate, helping end their seven-year spree.

Today, automatic license-plate cameras administer everything from speeding tickets to highway tolls, and some police cars even have automated plate readers. Additionally, an endless number of security cameras at toll booths, intersections, businesses, and homes record traffic around the clock. Reisner told me of one episode where a landscaper robbed and killed a woman, then got caught on camera in her Cadillac Fleetwood on his way to use her stolen debit card.

Although license plates are over 100 years old, Vehicle Identification Numbers (VINs) weren’t even required by law until 1969. VIN databases include information on the vehicle’s current and previous owners, when it was bought and sold, whether it has been damaged, and if it has open recalls (important for civil lawsuits). Criminals often sell cars to get rid of evidence, but unless the vehicle is sold without a title—which makes it illegal to drive in most states—detectives can still track the car down by its VIN. They are stamped in multiple places, and although a car can be burned, crushed, dumped in a lake, or even blown up, unless it’s melted down in a blast furnace, at least one VIN will likely survive. In fact, it was a VIN from the rear axle of the exploded truck used in the Oklahoma City Bombing that led investigators to the killer.

The things we leave behind

After a vehicle flees a crime scene, it can still leave clues. A Florida serial killer once left just a few short tire tracks near a crime scene, and the expert who analyzed them realized they actually came from a tire he designed while working for Firestone! After narrowing down the shops that sold those tires, police tricked their prime suspect into trading in his rubber for a free new set. After matching the treads to those at the crime scene, they got him.

If tire tracks are clear enough, scientists can identify more than just the brand and model. From the moment tires hit the road—even identical ones—they wear in unique ways. These imperfections help single out a specific tire from millions of copies. The ringer for the case above case was a pebble stuck between the treads, which left a telltale mark in the tracks.

Multiple Forensic Files episodes focused on hit-and-run fatalities, where a single collision can leave thousands of tiny clues. Musing on what motivates people to flee the scene, Reisner said, “Just panic, fear, desperation. Those things kind of erode morality sometimes. Perhaps they’ve been in zero trouble in their whole lives and they think, ‘Maybe I’ll get away with this.’”

Frequently, they don’t. With just a few fragments of broken plastic, experts can identify a vehicle’s make and model. Vehicles can also leave marks on a victim, like when investigators matched a Square Body Chevy grille to identical bruises on a little girl’s body.

With millions of similar cars on the road, this evidence typically serves as a starting point. Law enforcement can announce what make and model they’re looking for, and witnesses can provide tips like, “My neighbor said he just hit a deer, but his truck perfectly matches the description from a hit-and-run scene.” Broken glass can also be matched to vehicles, although it’s not always precise. Palenik explained that scientists can’t always use glass to pinpoint a vehicle’s exact make and model, but if they already have a suspect’s car, they can match glass from the scene to that damaged vehicle.

When it comes to automotive paints, identification gets way more specific. “If somebody [or something] gets hit by a vehicle, there’s a decent chance paint will be transferred, whether it’s a smear or a chip,” Palenik said. “And if you find that chip and you can trace it back to a car, that can provide some pretty high-impact evidence in an investigation.”

As all car nuts know, paint colors vary by brand, model, year, trim package, etc. That paint isn’t just “red,” it’s “Ford Race Red” or “Chevrolet Radiant Red Tintcoat” or “AMC Vineyard Burgundy,” and scientists can tell the difference.

“Several decades ago, the criminal justice communities in the U.S. and Canada decided to build the PDQ, or Paint Database Query,” Palenik said. “It’s a collection of paint samples, and they reach out to manufacturers of vehicles and attempt to get a chip of every single paint of every single vehicle made.” Palenik and his team can then take unknown paint from a crime scene and match it to samples in the database, helping investigators narrow down what car they’re looking for.

It’s what’s on the inside

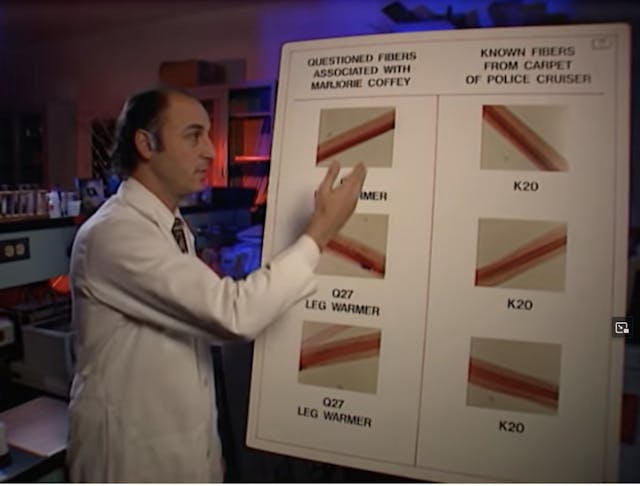

Not all evidence comes from the car’s exterior, of course. Vehicle upholstery and carpets often shed microscopic fibers that stick to clothes and bodies. In one Forensic Files episode, carpet fibers on a dead woman’s body were traced back to a police officer’s Chevy Caprice. In an ironic twist, the high-ranking officer drove the only Caprice with a fully carpeted interior, instead of the department’s basic cruisers, which only had rubber mats.

Just as automotive fibers left on someone’s body can prove they were in a car, evidence left inside the vehicle can do the same thing in reverse. “We see quite commonly that [dead] people are transported in blankets, or in some sort of rug,” Palenik said. Those items usually leave microscopic fibers inside the car.

“Cars are very good keepers of evidence, no matter what people do,” Reisner told me. “You know they tear up the flooring in the trunk and the cops go in there with Luminol and they find there was blood in there. Or even simple things, like it’s a 5-foot-3 person’s car, and the driver’s seat is moved way back, so they know the short owner was not the one who drove this car to the murder scene.”

Fingerprints on steering wheels, gearshifts, and various knobs are obvious clues. Bblood, hair, skin cells, or other forms of DNA can hide in cracks and crevices. Even the best automotive detailer in the world will overlook something, as was the case when a single cat hair found in a trunk helped solve a murder. In another hit-and-run episode, the perpetrator managed to clean, repair, and sell his Jeep Grand Cherokee to a dealership hundreds of miles away, but police tracked it down by its VIN and managed to find a tiny bit of evidence.

“It had to have been washed a million times,” said Reisner, recalling the episode. “But they still found arm hair from the victim stuck in the seam of the side view mirror.”

Vehicles collect all kinds of unexpected evidence in unexpected places, from tree seeds in a truck bed to bite marks in a rubber trim piece. As Palenik told me, knowing exactly what to look for can help investigators save time. Frequently, he searches car interiors for microscopic gunshot residue. “When you fire a gun, there’s a plume generated,” he explained. “Metals can precipitate in the gas and form these tiny particles that you can’t see.”

He’s even tested an interior for fireworks residue after three men were killed in a crash allegedly caused by lighting fireworks while driving. But his strangest automotive evidence came in the form of a dried vegetable.

“Were were given these crumbly gray chunks . . . We thought they were biological, perhaps human. Under the microscope, we determined the cellular structure was that of potatoes.” It turned out someone attempted to use a potato as a homemade gun silencer (which doesn’t really work). Bits of the vegetable were left in their car. Additional tests determined the potato did indeed contain gunshot residue.

Even simple soil can provide a wealth of information. In one Forensic Files episode, investigators used mud on the wheel wells of a Jeep Cherokee to tie the vehicle to a specific gravel parking lot where a gruesome drive-by shooting occurred. In the famous 1960 kidnapping and murder of beer magnate Adolph Coors III, distinct layers of mud on a car bumper helped prove it had visited multiple crime scenes in chronological order.

Reconstruction sites

Not every car accident is a true “accident.” The science of accident reconstruction helps find the truth. At the crash site, investigators record distances, road features, skid marks, and vehicle damage. These, combined with data on vehicle weights, tires, and road surfaces, can be used to calculate vehicle speeds and directions leading up to the crash.

In yet another episode involving a Jeep Cherokee, a police officer investigating a fatal collision was suspicious that there was too much blood inside the Jeep for the amount of damage done to the outside. Plus, the driver’s wife had died, but he had only minor injuries. Accident reconstruction proved the crash was too slow to be fatal, and the woman had been dead before the impact.

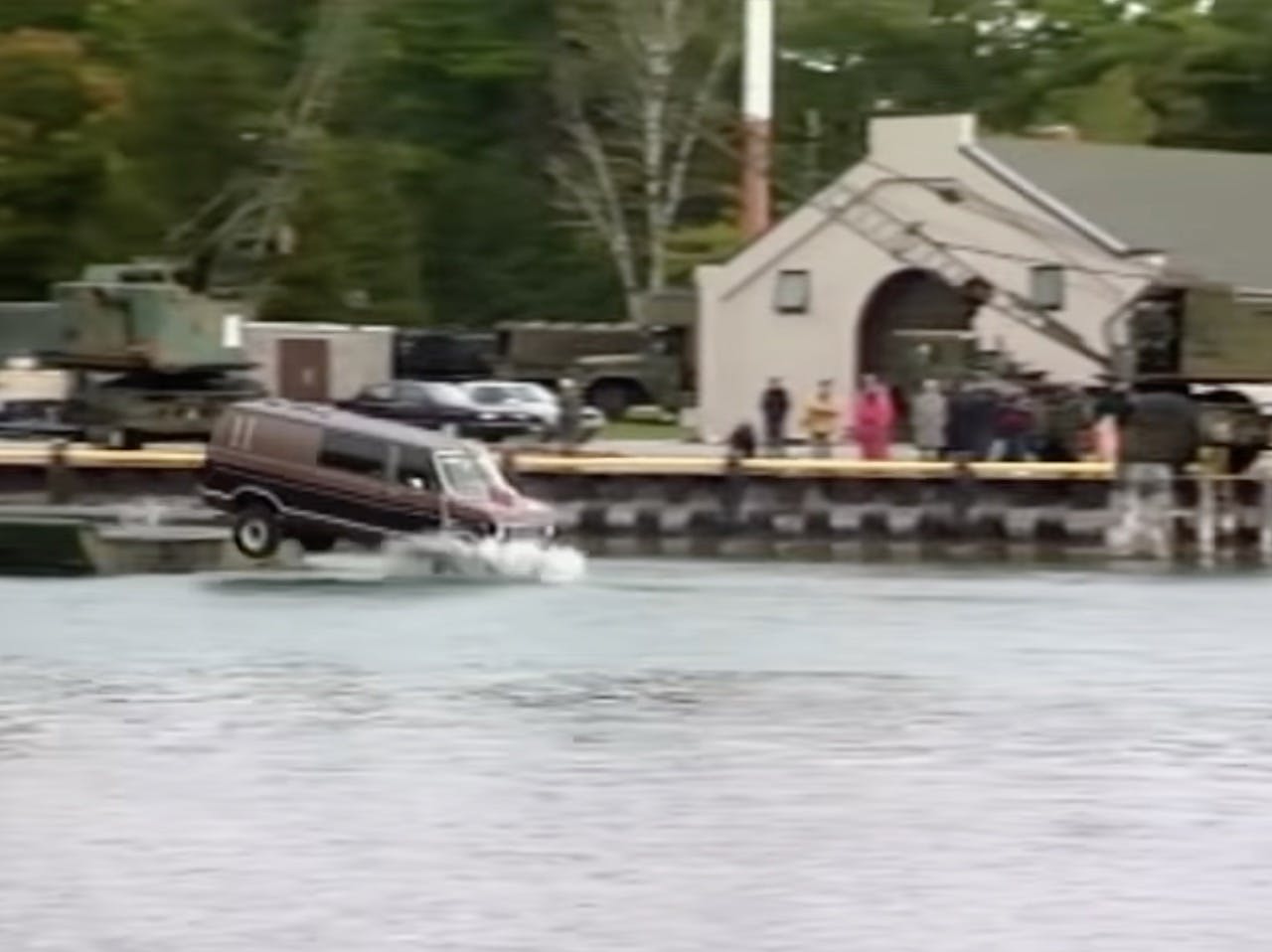

In one case, a lack of front-end damage proved a pickup truck was gently eased into a lake, rather than crashed into it at high speed. In a similar episode, police found a plastic bottle cap wedged in the throttle mechanism of a Mazda, functioning as homemade cruise control to cover up a murder. “They were trying to make it look like the driver drifted off to sleep and crashed into the water,” Reisner said. “But the car made a perfect 45-degree turn . . . a perfect straight line into the river.”

Some car crimes involve arson investigators, such as the episode where a mechanic tried to make a garage fire look like a fuel-filter change gone horribly wrong. But when investigators pointed out that a half cup of diesel fuel shouldn’t send an entire building up in flames, his elaborate insurance-fraud attempt fell apart.

The road ahead

Forensic Files originally ran from 1996 to 2011, although CNN relaunched the series in 2020. The old episodes may have outdated music and cheesy special effects, but the science holds up, and the driving reenactments are actually quite good. Today, the evidence generated by cars has only become more complex, as modern vehicles come with event data recorders that track when we accelerate, brake, shift, signal, use infotainment, and more. But solving car crimes still takes hard evidence and expert analysis, as Palenik can attest.

A lot has been said about how you can judge a person by what they drive, and it seems even more true when it comes to solving crimes. A single paint chip or carpet fiber can be the thing that sends someone to prison (or gets them out). But beware, if you think you’re smart enough to pull off the perfect crime after reading this, Rebecca Reisner says otherwise: “People have been doing that for years. Cops will figure it out! We’re not all the geniuses we think we are.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Interesting article! The only one that made me scratch my head was the fuel filter. I mean, yeah, there’s not a ton in there… but then it could light my oil/grease covered frame on fire, which would then light the rest of the car, which could burn pretty well, and then my garage could go up. Saying there’s not enough fuel in the fuel filter to burn a garage down is discounting all the other fuels that fuel filter fire could ignite.

The key word is “diesel” in the fuel filter. Diesel fuel’s flashpoint is much higher than gasoline and will not light unless above a temperature of about 125~200 degrees Fahrenheit (Mythbusters even did this in an episode I believe, trying to light a trail of diesel fuel on the ground). Below that, you could hold a lighter to the diesel and it would not just burst into flames like gasoline (flashpoint of -45F, the reason gasoline ignites well in cold weather, and diesels can struggle). Hold the lighter there long enough to raise the temperature above that threshold, sure, but it would be nearly impossible to “accidentally” or “spontaneously” start a garage fire with diesel as the first thing burning started by say a spark. I would guess this was the key in the article’s investigation, that the guy tried to claim a spark or something lit the fuel in the filter, which is not possible or at least nearly improbable.

So if you are going to commit a crime, ride a bicycle?

Or TG put on a pair of skates & skate away!

Amazing article! Very interesting. Thank you.

Very cool article. If you do the crime, someone will be looking to find you.

Very interesting article for us crime / drama / mystery writers (both novels and screenplays in my case). I’ve actually utilized a number of these forensics in my books / scripts. Great stuff, Joe!

Forensic Files was a great show. I’ve seen every episode at least twice. They really should resurrect this series.

Now if I could just find the vehicle that knocked my fence over the other day. Clues: Bumper is about three feet high with a long overhang. Damage likely on the rear.

I find it interesting when you said that it can still be possible to track a vehicle that is used in a crime as long as it has a title through its VIN. I can imagine how that kind of information is one of the useful details professionals can use to have a forensic crime scene reconstruction process. Then they can use all of those to actually tell who the suspect is and what really happened. https://www.bevelgardner.com/crime-scene-reconstruction