Mud Wrestling: At some point in the ’93 Camel Trophy, we began naming the leeches

Back in 1993, I had just been fired as executive editor of Car and Driver. “Gross insubordination” was the charge, although I couldn’t see anything gross about it. I was demoted to staff writer and my new office was on the dark side of the atrium at 2002 Hogback Road. I spent several hermetic years therein, in what staffers—including Hagerty Drivers Club magazine editor-in-chief Larry Webster—called “The Cold Room.” Its purpose was to protect 50 years’ worth of C/D back issues.

I mention this dishonor because it enabled me to enlist in the 1993 Camel Trophy, then a worldwide competition in which four-person teams from 16 countries drove Land Rovers off-road in nations where there was no choice but to drive off-road. That year, the event was in Sabah, Malaysia, the northern state of Borneo. It would last three weeks. But first I had to undergo six weeks of training in Grand Junction, Colorado, at Land Rover’s headquarters in the U.K., and in Italy, for reasons I think related mostly to alcohol.

My off-road trainers were American mountain man Tom Collins and British ex–SAS sapper/survivalist Vince Thompson, who resembled actor Karl Malden in camo. “I don’t care if you die in Borneo,” Thompson informed me. “That’s easy. All that worries me is if you’re crippled or maimed. Know why? ’Cause then you become a bloody burden.” The U.S. team’s principal drivers were Mike Hussey, a geologist from Vermont, and Tim Hensley, a contractor from Oregon. Photographer Peter MacGillivray would occupy the left-rear seat. I was the relief driver and also the guy shouting out rally coordinates. What I mostly said was, “I don’t know.” All four of us first had to prove we could run 5 miles, swim a lap underwater, remove a tire from a wheel using an ax only (really), and fix any component on the Discovery Tdi.

I vividly recall a preparation rally on a plateau in the Rocky Mountains at 4 a.m., where I got us lost. I said to Hussey, “Let’s stop on that flat snowy place up ahead, and I’ll get my bearings.” He drove to the middle of that flat snowy place and said, “Why would there be a flat snowy place in the mountains?” Whereupon the Disco burst through the ice and sank to its door handles. I remember someone’s Nike shoe floating an inch below the steering wheel. This hypothermic pickle delighted our instructors, because it took four hours of winching to extract the Disco. Talk about fun.

There was no ice in Borneo. In fact, when we arrived in the capital city of Kota Kinabalu, the temp was 105 degrees. My One A Day vitamins swelled into flaky pellets the size of June bugs.

We would be sleeping on the ground for 22 days, sharing that surface with tiger and buffalo leeches; moths with 12-inch wingspans; poisonous centipedes; maybe 800 varieties of fluorescent snakes including a green banana viper that lunged at an Austrian competitor and whose bite, assured our Malay translator, “was not that bad—just three or four days of fever, then some heart trouble.” Further, there were carnivorous civets that actually can eat chrome off a trailer hitch; Sumatran rhinos; orangutans, one of whom a week prior had attacked a man and torn his pants off; a tarantula-like mygalomorph that eats birds; and dragonflies the size of drones. Oh, I almost forgot: fruit bats so big that the Malays called them “flying dogs.” In all of my travels, Sabah is the only place where, upon awakening in sickly fog every morn, my first utterance was, “F*ck.”

Just for starters, defecating in the jungle became a test of will. As you squat defenseless, you notice leeches inching toward your ankles. In one case, a mirror-shiny black snake slithered 6 inches from my Army-sourced Vietnam combat boots. You learn to perform a comical sideways duck-walk while excreting, a skill useful nowhere else on the planet except maybe on the side of an active volcano. Unavoidable splatter is involved.

Once a week, we ate our anti-malaria tablets. It was far and away the finest meal of the week, because the pills induced mild hallucinations. We had no liquor. I recall our photographer overdosing on Lariam, then insisting that actresses Sally Struthers and Suzanne Somers were the same woman, a notion he reiterated for 40 minutes. That was followed by a four-man argument about what day it was. We eventually drew palm trees on the Disco’s dash every morn to keep track.

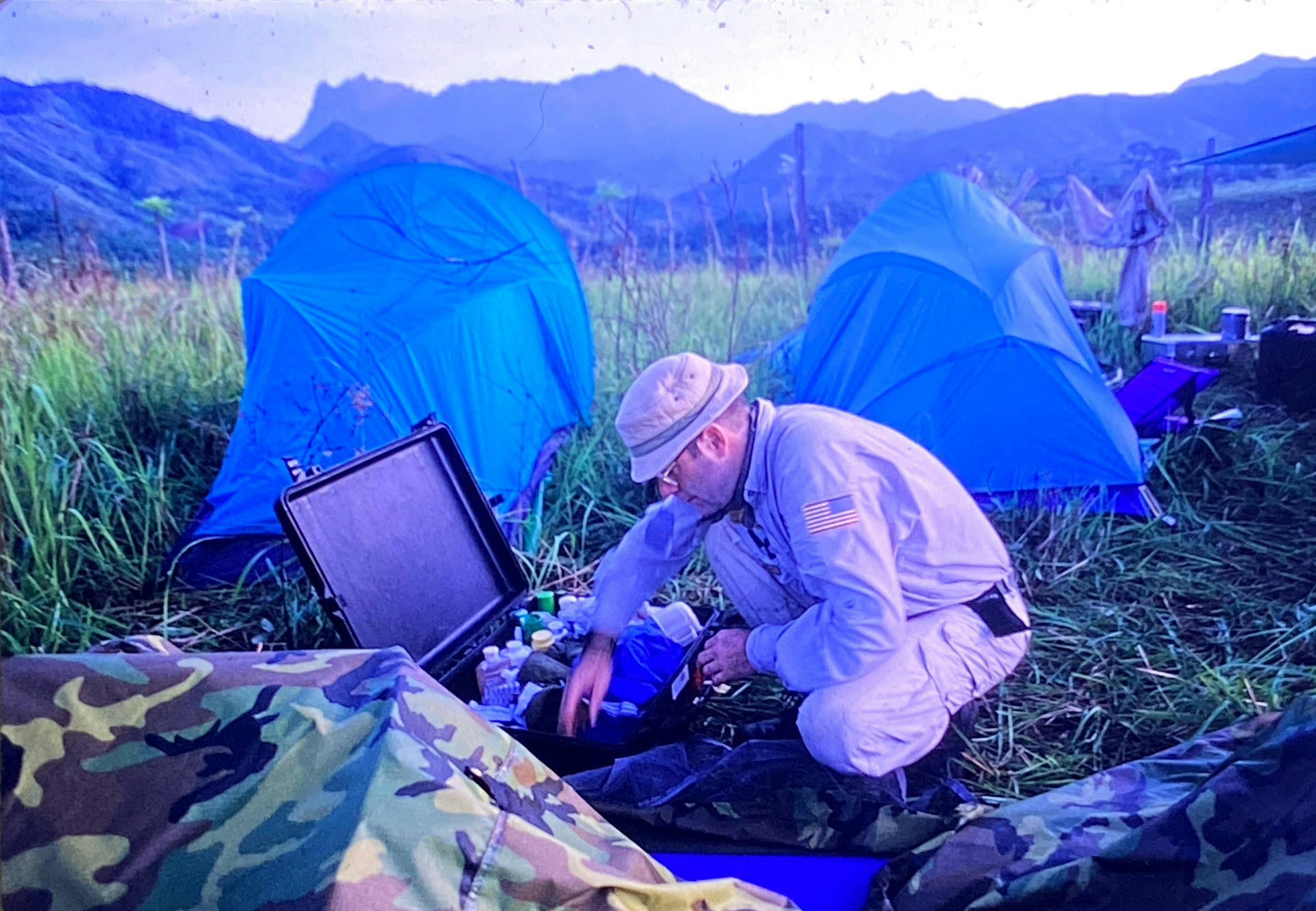

Sabah is famous for creepers, strangler ferns, orchids, carnivorous plants, palm oil, and mahogany. It is further famous for malaria; dengue fever; hepatitis A and B plus the rest of the alphabet; dysentery; leptospirosis; typhoid; water full of so many bugs that a cup of it can walk away; soggy piecemeal toilet paper; and Thompson’s infamous fire-dance sh*ts. I was pleased to learn that head-hunting had been banned. Each of us underwent a blood test so that, as the organizers kindly put it, “You might safely help a fellow competitor who needs a transfusion.”

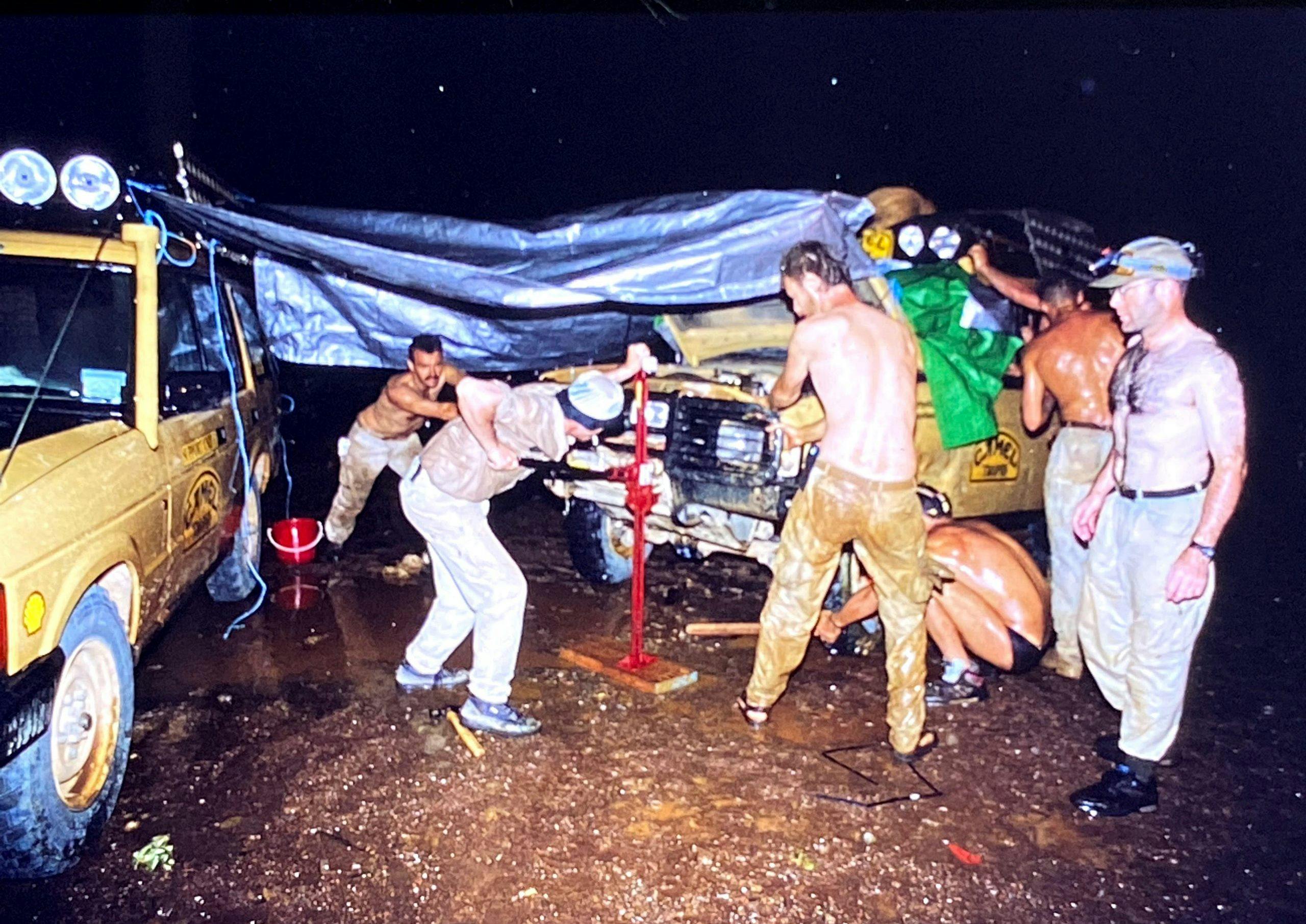

In fact, we had an actual physician, Dr. Mike Irani, who followed our 64-man convoy. His job mostly was to remove leeches and tend to the two-dozen bottles of single-malt Scotch he had smuggled aboard his jury-rigged 4WD ambulance. There came a moment when the Dutch team rolled their Disco, sprinkling the jungle with a front differential, one door, one wheel, the windshield, six Pelican cases, and two Cibie lights. Dr. Irani was summoned to affix a cervical collar on the Dutch driver’s filthy neck. Hussey said, “Guess the guy broke his cervix.” For that sparkling bon mot, we were sentenced to seven hours of mechanical assistance. Hensley performed some arc-welding while standing in 6 inches of water.

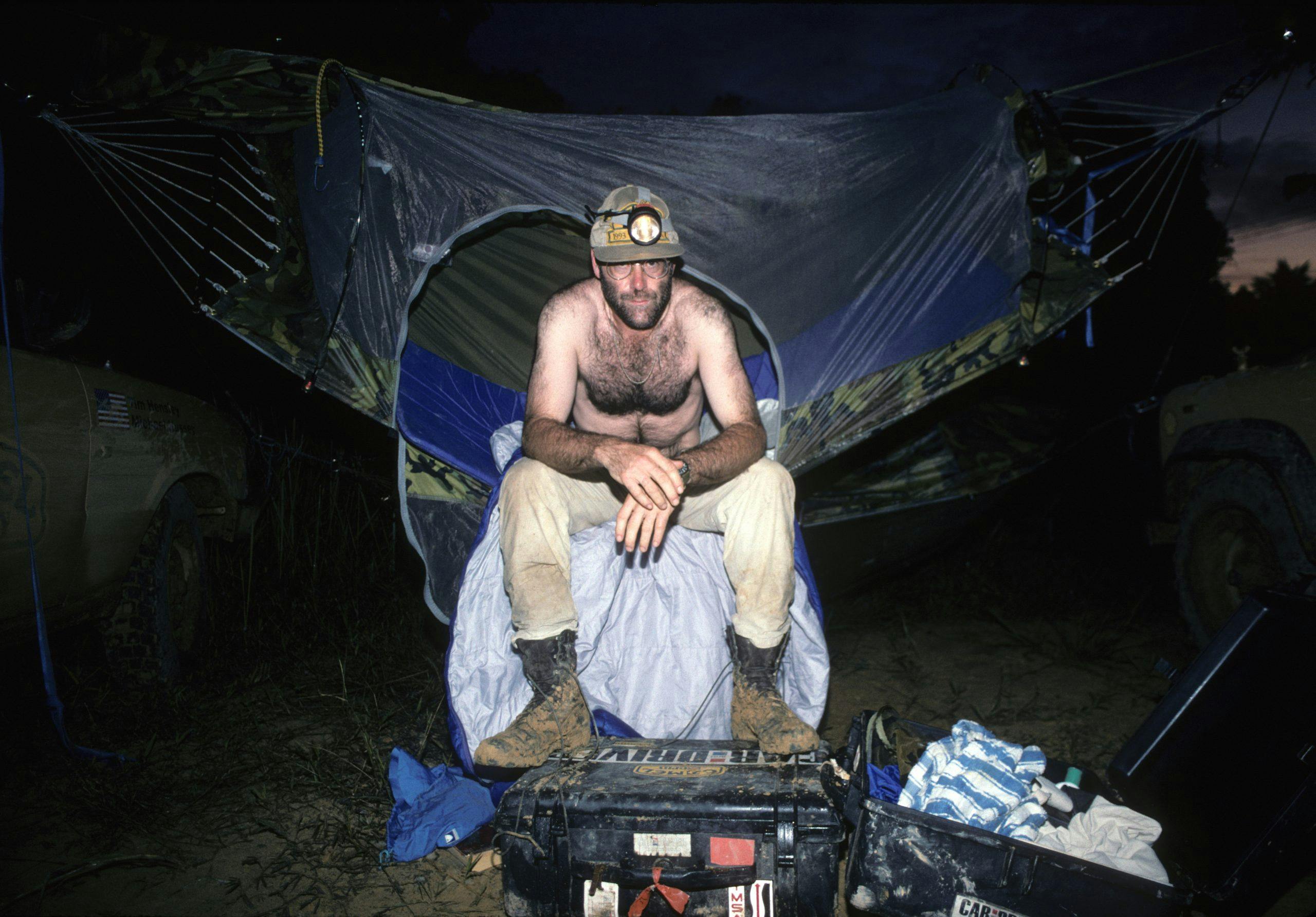

Sabah hugs the equator. Each day is a replica of the former. By 10 a.m., the temp hovers in the high 90s. Precisely at 4 p.m., rain falls in globules, hitting the windshield with a splash the size of a Post-It note, easily overwhelming the Land Rover’s wipers. The rain then turns to steam, which turns to fog that lingers until dawn the next day. Nothing has a chance to dry. Nothing, including the Disco’s seats. Before every dinner, I stripped to my Y-front Jockeys to dry my shirt and pants on the Disco’s exhaust manifold. My shirt was imprinted with black burns, as if it had been on a grill. Because it had. Hussey developed a case of athlete’s foot that could have felled all of the Detroit Lions. His toenails fell off. We all grew red zits over our chests and thighs, then brown boils erupted in our armpits. Hensley once had three leeches simultaneously sucking his left calf. He didn’t even know—had to be told. His pants were soaked with blood for a good 10 inches. Dr. Irani prescribed Scotch.

The record holder, however, was a funny Russian man named Yuri Strofilov, who endured 20 leech suck-a-thons. Dr. Irani said, “The trouble is, he won’t stop bleeding.”

I began sleeping on one of the Disco’s aluminum sand ladders, to keep my backside free of muck and biters. On any given night, I’d sleep three hours, with a bonus hour of mild delirium, then awaken at 5 a.m. to the horrifying screeching of howler monkeys. We were always tired. One day we traveled 2.8 miles in 14 hours of bridge-building, winching, and shoveling mud out of the wheel wells. In just a week of this festival of filth, we resembled mud-encrusted barbarians. Dr. Irani called us “arboreal Hannibal Lecters.”

We’d been trained to make our bodies go limp inside the truck, because tensing up to counteract the relentless bouncing is overwhelmingly exhausting. I bungee-corded my head to the roll bar—a stroke of genius, because that night we had to sleep in the truck. For ventilation, we left the doors open, but then the overhead light was blazing. Hensley punched the thing in a blow so powerful that the lens and bulb splintered into sharp confetti and there was a fist-size concavity in the roof the next morn. “F*cker’s out now,” Hensley declared with satisfaction.

You will not believe this, but when anything major broke beneath our 111-hp diesel Disco, the accepted procedure was to tip the vehicle on its side so we weren’t struggling in mud. Once it was fixed, we’d winch it upright and try to sort out why MacGillivray’s sunglasses and Hensley’s compass were in my drinking cup. All four of us became all-star miracle masters of Warn winching: sideways, backward, underneath. We once deployed a newly invented jack that abused the laws of physics and required a spiderweb of cables and pulley blocks that could easily have killed all of the Flying Wallendas. This pig-on-slime contraption actually lifted a competitor’s 2.5-ton Disco out of the muck. I expected a cable to snap and decapitate someone, so I ran to the end of the convoy to summon Dr. Irani. He was snoring. I startled him. His first words were, “Does this have anything to do with Madonna?”

Our food was freeze-dried gloppola that tasted like rabbit intestines with chemical gravy. So, we became desperate for fruit. We picked some green bananas and developed the fire-dance sh*ts. We stole a pineapple and stored it in our cooking bag, where it broke a can of cooking fuel and marinated into a Molotov fruit cocktail. We ate it anyway. “A grisly gut wrench,” Hussey predicted, but, no, just more fire-dance sh*ts, although this time with a chance of real fire.

I learned some Malaysian words: “Buaya” means crocodile, a word handy while we were mired on the banks of the Padas River. I further learned “katam tebu”—black and yellow water snakes, whose venom can kill a man in 20 seconds. Also “kumbang,” which is a beetle the size of your thumb. The Malays deep-fry kumbangs for lunch. By then I’d become so fatalistic with end-of-times digestive eruptions that—I swear this is true—I ate one. Tasted like Doritos.

The Polish team hit a stump that ripped off a wheel. It tore all five lug nuts through the steel. I didn’t know that was possible. One of the Canary Islanders shattered his arm and lacerated his buttock. The chief driver of the Swiss team, Markus Graf, began driving in figure eights because he’d unknowingly contracted dengue fever. He was airlifted out. So was Italian driver Matteo Ghiazza, whose foot had swollen until he couldn’t remove his boot. “Bitten by something,” was Dr. Irani’s insightful hypothesis. Then a final airlift for the Turkish team’s Hakan Dalokay, who’d collapsed from dehydration.

At breakfast on our 17th day, photographer Peter MacGillivray put an arm on my shoulder and led me out of camp. “John, buddy, I haven’t told anybody this,” he said in a whisper, “but I knocked up my wife back home.” I nodded. “And, well, if you make it back, could you take care of her?”

It occurred to me that we had become Army Rangers but with weapon training confined to Swiss Army knives. If you’re a real Ranger, feel free to write a letter of outrage. But I bet $50 we could have joined your unit undetected, apart from our phenomenal personal body stench, and outdriven any of you in the jungle. Plus, by then, I could whip up some sautéed beetles.

On the final day, we halted on a beach facing the South China Sea, where there was actual wind, something we had not felt for three weeks. We swam, lit a driftwood fire, then incinerated our clothes and boots. The uppers of my boots had separated from the soles two weeks prior. My socks had long since been discarded in mushy pieces resembling oatmeal. We purchased khaki shorts from a sidewalk vendor, the salesman demanding 14 Malay ringgits (less than $6). We drove back to Kota Kinabalu barefoot and naked except for our new shorts.

In civilization that night, we ate fried ox lung in coconut rice with star-fruit pulp. To us, it tasted like chateaubriand from Escoffier. “Lung Fu,” I named it. At the hotel, I weighed myself: 143 pounds.

Here’s the thing: We won. We were the first and only U.S. team to conquer any of the 19 events, for which we received a sparkling bronze trophy; TAG Heuer watches (mine lasted eight months before dying and it was too expensive to fix); a scar on my nose from an unplanned speed-of-sound hammock dismount; and a 1-pound lump of amber I found in the volcanic Maliau Basin, whose first American visitors were us, or so the Malays said.

I’ve never known whether this self-inflicted gambol was wonderful or disgraceful. Logistically, it closely resembled a military invasion, with all of us wearing identical uniforms, and residents of the interior jungle villages certainly viewed it as such.

In the end, the U.S. team was better prepared than 15 others, and to this day, I remain proud of that. But what we mostly did was inflict 1000 miles of meter-deep ruts, build 25 rickety bridges that collapsed within weeks, convert a ton or two of aluminum sheetmetal into wads of Reynolds Wrap, and deplete a cigarette company’s PR budget by $4 million ($8 million in today’s dollars).

Six years later, Land Rover and Camel decided they wouldn’t do it again, either. Too many environmental concerns. I concurred.

I still have a copy of the “you might die” waiver I signed. And on my dresser rests the Camel Trophy patch that fell off my rotted uniform. Twenty-eight years later, it still stinks.

***

Not exactly a race

If you remember the former International Race of Champions (IROC), that’s what the Camel Trophy resembled, except in muck. Competitors drove identical Land Rovers—in this case, Euro-spec diesel Discoverys—modified by the company with rollcages, winches, snorkels, heavier-duty suspension/shocks, roof racks, larger fuel tanks, and a couple-hundred pounds’ worth of recovery gear: snatch straps, sand ladders, farm jacks, and so forth. Land Rover and Camel-brand cigarettes paid for everything, costing them millions every year.

The event ran for 19 years, with Land Rover’s finest off-road engineers and test drivers tutoring teams they deigned to invite. Each team comprised four men, with as many as 16 teams per event, one per country. Competitors originated from most major European countries, plus the U.S. and Russia. Each was given six to 10 weeks of training beforehand, in their home countries, in England, and in Italy. The events’ organizers and planners were either LR employees or plucked from the British military, with ex-officer Iain Chapman the putative commander—think General “Monty” Montgomery, here. Chapman and colleagues selected a different far-flung locale every year: Sumatra, Madagascar, Papua New Guinea, Guyana, Mongolia, Tanzania—any country where off-roading was an isolated and persistent nightmare.

At each event, the half-dozen LR organizers rated competitors on an arithmetic scale, noting skills at winching, retrieval, bridge-building, willingness to help stricken colleagues, driving precision, and time/speed/distance rally placings. Score the most points and you’d win.

The vehicles were always a distinctive school-bus orange, what LR called “Sandglow.” The Disco that won America’s lone victory was shipped to the States and was sought after by off-road aficionados, despite having been beaten to orange marmalade in Malaysia. That one and only “real” Discovery could be identified by the hand-drawn palm trees on its dash—its occupants’ method of counting days. It was said to have been destroyed in a crash with a bridge abutment. But that was never confirmed.

That was an outstanding story! I’m grateful that I didn’t participate. The story caused me to recall a seven day canoe trip with a friend to the Boundary Waters area, between Minnesota and Ontario. While we didn’t encounter the horrors that the Camel folks did, An entire week without seeing people was blissful.

I have done week-long excursions to the Boundary Waters, too. Unforgettable experience, but definitely up there in the scale of the term “Roughing it”. My father nearly lost his finger on one trip when he slipped with a fillet knife, and it became infected. The finger was saved, but the tendon was severed, and he cannot bend it anymore.

Trip across the humid mosquito infested Jungle? No way, Houston is bad enough.

I absolutely love John Phillips’ writing style. Too bad that he didn’t go into further detail regarding his “Gross insubordination” episode at C/D. Always looked forward to his articles and was bummed when his stories no longer appeared in the magazine. Fairly recently, after an editor change at C/D with Tony Quiroga in charge) John has resurfaced with a couple of new articles. It has been a long time since his absence that I’d laughed while reading C/D … just like I did while reading this article. Keep it up John!

Thoughts: 1) Glad nobody died (I think)

2) Sounds like it would make a great movie (certainly would have been a top viewed youtube vid)

3) What was the point exactly??