Lou Rawls, “Tobacco Road,” and the night my father crashed the SS Chevelle

The song was “Tobacco Road” by Lou Rawls, and in those Saturday afternoons before Dad crashed his ‘69 Chevelle SS 396 convertible in a street race, he’d leave it on the record player to spin again and again. We started every weekend by cleaning his car inside and out. I was four years old in 1969, but I still had my tasks to accomplish: wheels and tires, bumpers and hard chrome parts, things I couldn’t mess up.

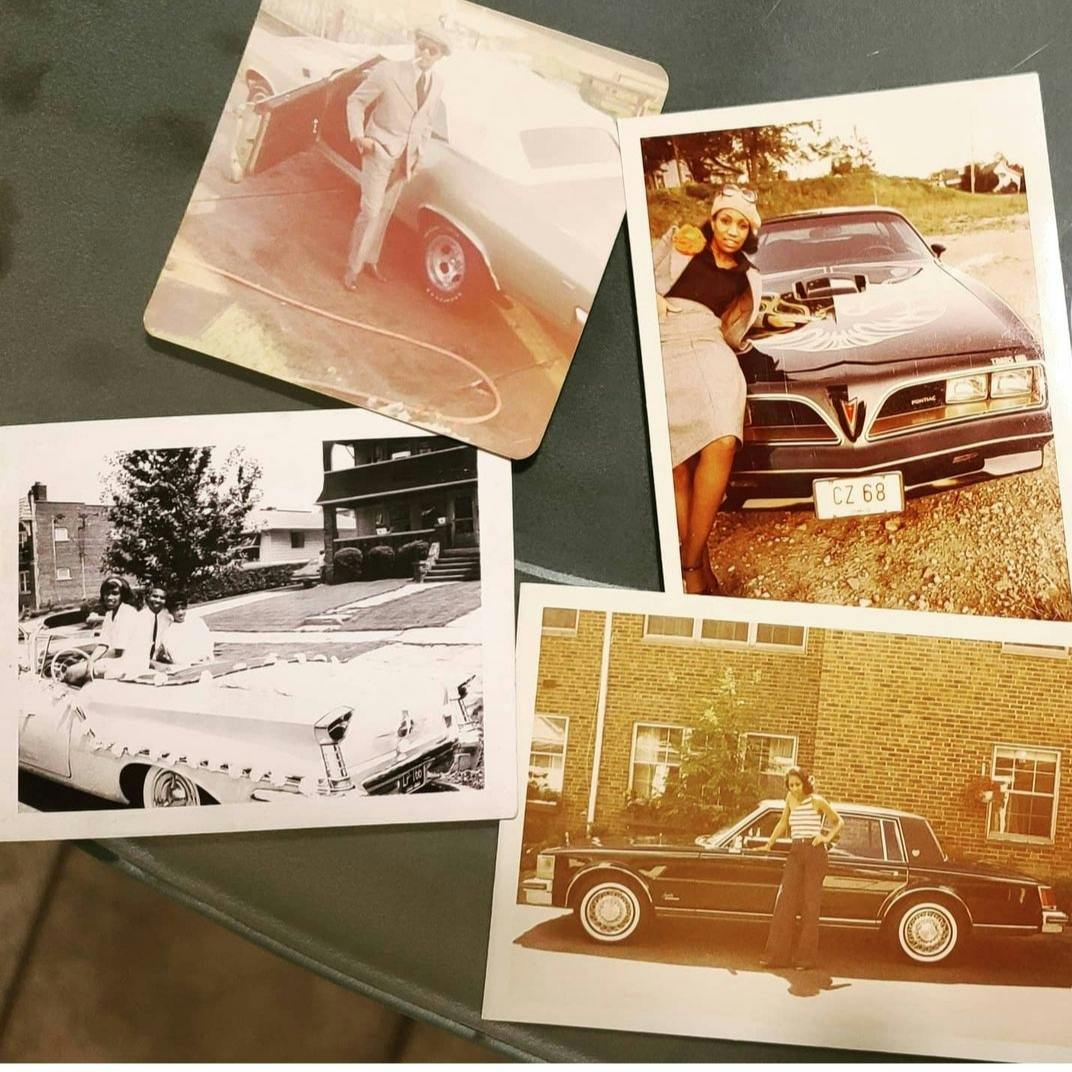

Our family was known for having clean cars. Maybe that’s not much to be known for. But it’s something. When I saw my father right before his death seventeen years ago, his Nineties Astro was clearly past its best days and there was rust at the bottom of every sill. Yet around the rust the paint shone with the deep gleam of multiple hand-rubbed wax applications. On his tires, the distinction between white letter and black surface was razor-sharp. He climbed out of the Astro and shuddered when he spoke to me. There was something killing him. I didn’t see much of the man I remembered from the summer of 1969.

Back then there was a muscle car scene in Cleveland, and there was also a Black muscle car scene. You have to think of it like two weather patterns interacting; sometimes the overlap was a place of calm and sometimes it was a place of storm. You could get a race in the late evenings. All that “pink slip” business didn’t really happen. The white guys might run for pride, but the Black guys would always run for money. Even if it wasn’t much. That was part of it. Made it real.

General Motors dominated the scene the same way they dominated the rest of automotive America. When the Camaro showed up it became omnipresent almost immediately. Hard to believe it now, but the Camaro had a big part in the Black scene because it was cheap. I don’t mean it was a piece of junk. Only that the cost of entry was low. Cheap to buy. Cheap to make them go fast. For my father to run against the Camaros successfully, he had to have a little something extra. It wasn’t necessarily about modifying the cars. You bought the best factory setup you could and then you kept it running right. Which wasn’t easy in those days, with carbureted cars and variable fuel quality and the fact that they’d just break.

Every weekend, my father’s group would meet up at my uncle Johnny’s place. He was 33 against my dad’s 24, drove a Coupe de Ville. My aunt Betty had a bit of a hot streak so Johnny bought her a ‘69 Nova with the 307, sky blue with black vinyl top and interior, automatic on the column. We’d all sit or stand in the kitchen, talking about the races from the week before, who’d picked up money and who’d blown an engine. Betty would pour the men VSQ brandy into tumblers, never more than two fingers’ worth at a time, and they’d sip it slow.

I don’t know how exactly Dad totaled that Chevelle. He went out one night with the car, looking for a race, and came back on foot. Uncle Johnny knew, but he didn’t share those details with me. All I knew was that it was time to find a new car, one that could run heads-up with whatever else was out there.

We didn’t have new-car money to spend; the Chevelle hadn’t been insured against collision. So Dad and I picked through what was available, reading the newspaper ads, making careful calls, always conscious of the idea that not everybody in Cleveland’s ritzier suburbs would want us showing up on their doorstep for a test drive.

After a lot of false starts we found a 1965 GTO convertible, maize yellow with a four-speed manual. The left rear quarter panel had been crumpled by the owner’s kid. In 1969, a four-year GTO with body damage wasn’t worth much. Particularly if it wasn’t a Tri-Power, and this one wasn’t. Dad bought it and set about making it right. There was an underground economy, men whose bosses would let them keep a body shop open after business hours, that kind of thing. That was how we got the GTO straightened out and ready to run.

By the time the Goat was worthy of appearing at Uncle Johnny’s, Lou Rawls was off the record player, replaced with something else I don’t remember. And the street race scene was starting to cool off. Lot of attention being paid by the cops, a season’s worth of cars coming out that didn’t seem to run as hard as last year’s models. The fleet parked outside Johnny’s house started to change. In 1973 my father called it quits for good. Bought a ‘74 Thunderbird. It was all show and no go.

The ‘Bird was a reflection of my father’s new economic status. He had a hustle going on. And in the years that followed, the old man would pay cash for a lot of serious hardware, everything from Stingrays to Sevilles. But that’s a story for another time …