Foxtrot: Winding roads, a giant fish, and an ’86 Mustang

The evening before my flight to Charlotte, North Carolina, my phone involuntarily updated and, in the process, wiped out thousands of photos. Numerous digitally preserved memories, scrubbed clean, all at once. Everything is temporary.

Should I have backed up my cell shots to the cloud? Absolutely. Did I? No. For some reason or another, the typically automatic backup process hadn’t triggered for about a month. By the time Cameron’s No Good, Very Bad iPhone Photo Massacre of 2022 (so named in the textbooks of future generations) struck, it was too late. Troubled as I was, there was no time to mourn; more pressing was the matter of packing enough clean underwear for a three-day road trip in my boss’s 1986 Ford Mustang GT.

The plan: Meet editor-in-chief Larry Webster and his son down in the Queen City. Spend an evening at Bowman Gray Stadium watching stockers circle one of America’s oldest—and most unique—short tracks. Drive the Fox-body home to Webster’s house, while he flew back to catch a meeting.

Saturday night, the day of the race, it rained. A torrential downpour soaked Bowman Gray’s grounds, washing away all hope for competition that evening. Imagine traveling to the Louvre only to find it closed because the sprinkler system had gone off. Despite the setback, we stuck to the plan. Webster handed me the keys to his Mustang that night. I would ride at dawn.

Ford unveiled its third generation Mustang in 1978. Lighter, shorter, and with much less chrome, the pony car riding on Ford’s new Fox platform was a radical departure from any previous Mustang. “Put everything you’ve learned about Mustangs into the Inactive file,” wrote Car and Driver in a review of the 1979 model.

The Mustang—along with its equally-fresh stablemates, the Fiesta, and Fairmont—received favorable grades from reviewers following its transformation. Ford had finally trimmed the fat and the new fighter was leaner and more nimble. By 1986, the Fox body generation was coming into its own. The Blue Oval had also ditched the carburetor in its legacy sports car, in favor of fuel injection. Another big boon was the GT trim that supplanted the short-lived Cobra Mustang. The Mustang GT’s 302-cubic-inch V-8, which was the most powerful engine in the 1979 model with 140 horsepower, now pushed past 200 and the venerable ’86 could lay down sub-15-second quarter-mile times.

Across the aisle, Mustang had stiff competition in the Camaro, which was experiencing a similar glow-up in the mid-1980s. Car and Driver pitted the two against one another in a performance test at California’s Willow Springs road course. Their conclusion: “Our overall feeling is that the 5.7-liter Camaro is more fun for blowing sludge out of your brain on a deserted two-lane, but the Mustang is the better all-around automobile. In all but the wildest maneuvers, it’s more coordinated, more comfortable, and more poised—in other words, a nicer car to live with.”

I left Winston-Salem early. The long commute back north to my home in Ann Arbor, Michigan, began with clear roads and clear skies. After a couple hours in the car, tossing through the gradual twists of Highway 89, I had to agree with that contemporary assessment, which has aged well. Less accurate is this bit of hyperbole from the same article: “Today, both the Camaro and the Mustang have enough power under their hoods to light a small city.” Imagine time-traveling back to ’86 with today’s 460-horsepower Mustang GT.

The Fox can still light up its driver, thanks to that engine. The deep growl from the set of Flowmasters out back helps. (And masks the creak of ’80s plastic.) As I shuffled through the gears of the Borg-Warner five-speed, leaving waves of V-8 noise in my wake, it certainly felt like I was setting land-speed records.

I stopped for lunch in Galax, Virginia. (The city’s intergalactic-sounding name comes from Galax urceolata, a leafy plant found throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains.) Galax’s primary industry is furniture, which means a turn down any side street often yields a pile of prepped lumber stacked stories high. The downtown is rather quaint, punctuated by small businesses like Canton Restaurant.

Canton has been a staple of Galax since the Seventies. It’s owned by a couple who divide and conquer when it comes to orders and food prep, and the restaurant is one of several Chinese-cuisine establishments owned by the family throughout the United States. I arrived on Sunday, sharing the dining room with the church crowd. As families discussed the local happenings and ran through the upcoming soccer practices and appointments for their children, I took note of a giant fish in a tank on the other side of the room. He didn’t have a name, the owner said, but he was a 13-year-old dragon fish. I asked how long dragon fish live. “I don’t know. You never know. They’re just like people.”

While waiting for a plate of chicken, I searched for a place to stay along my wandering route back to Michigan. I figured a couple hours more in the Mustang would be a great way to get more acquainted and close out the first day. Looking at the map, I found southern Virginia and the town of Pulaski. Another cool name. Once there, I located the Jackson Park Inn—a 1920s grocery warehouse renovated to house weary travelers such as myself.

Pulaski is nestled against Virginia’s portion of the Appalachians and is situated just a few clicks southwest of Roanoke. According to an ornate sign in its cute downtown, Pulaski sprang up at the coming of the railroad. Initially called Martin’s Tank, the town was renamed after Polish nobleman Casimir Pulaski. “The Father of the American Cavalry,” Pulaski saved George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

According to the National Library, “The British caught Washington in a precarious position with a clever flanking maneuver. It appeared that the Americans might be routed and Washington captured, but Pulaski—possessing no rank—asked Washington to give him temporary command of some cavalry. Washington assented and Pulaski skillfully led a counterattack, helping delay the British enough for the Continental Army to retreat and regroup.” Casimir was given chief command of the American Light Dragoons.

Monday morning, I made like a dragoon and rode my pony out of Pulaski. The new-for-’86 sequential port fuel injection, which provides one injector per cylinder, keeps throttle response lively. The Mustang and I bounded from stoplight-to-stoplight, finding an easy rhythm. I was a pair of taillights and Ford mud flaps.

I planned for this day to be pretty cut and dry. Once I was clear of the Appalachians, I completed a four-hour rush north along I-77, so that I could reach Pennsboro Speedway in West Virginia before sunset. Inspired by an episode of NBC’s Lost Speedways, where Dale Earnhardt Jr. and his cohost visit the famous abandoned race track, I decided to indulge my own proclivities for automotive archeology and pay a visit.

I-77, despite its status as an interstate highway, is an excellent ribbon of pavement for a road trip. Its somewhat dramatic curves and length connecting Virginia and West Virginia remind me of Pennsylvania’s I-80—a tourist’s expressway. There’s plenty of roadside beauty, especially through the Mountaineer State’s undulating countryside, and traffic hustles along fast enough to cover solid distance in a day of driving. I relished each opportunity to pass and watch the needle dive toward the speedometer’s 85-mile-per-hour terminus.

Time in the Mustang allowed me to reflect on the importance of those iPhone photos lost. Why did it sting? I ate the food, I watched the sunset, I did the thing. Yet there was comfort in saving those moments in a tiny black box. Why? Shouldn’t the memories in my own head be enough? Would losing some of them be so bad?

On my way up to the track, I passed a funeral procession with a Red Bull van bringing up the rear. I wondered if it was it part of the motorcade, giving the departed wings. Drive long enough by yourself and truly stupid thoughts like that start to sound witty.

Unlike today’s speedways, the Pennsboro is shaped like an imperfect egg, which would be fine if horses were still racing there like they did from 1887 until the 1960s. Even after years over overgrowth, you can still see the variances in banking, width, and turn radius. Eventually, auto racing took over the venue as far-flung speed freaks flocked to watch dirt all-stars battle for checkered flags. “The Hillbilly Hundred” and “The Dirt Track World Championship” garnered national attention. Now, the track lies dormant, year-round.

By the time I arrived at the old fairgrounds, the sun was low, casting an eerily beautiful glow across the field where the track once stood. As if it was a sign from the still-angered racing gods, a black cloud moved in over the sun the moment I set foot on the property, and with it came a sprinkling of rain. I walked the track, undeterred, imagining what it would’ve been like to be a fan—or even a driver—at Pennsboro. A river runs through the track and mid-corner bridges used to usher cars over the water. The front stretch buts up next to a knoll where fans would dig their seats into the soft hillside. Some of the structures like the ticketing booth, the Skoal Tobacco sign, and the bridge guardrails still stand. They aid in creating a mental picture of how Pennsboro looked in all of its glory. Tracks with this kind of character don’t get built anymore.

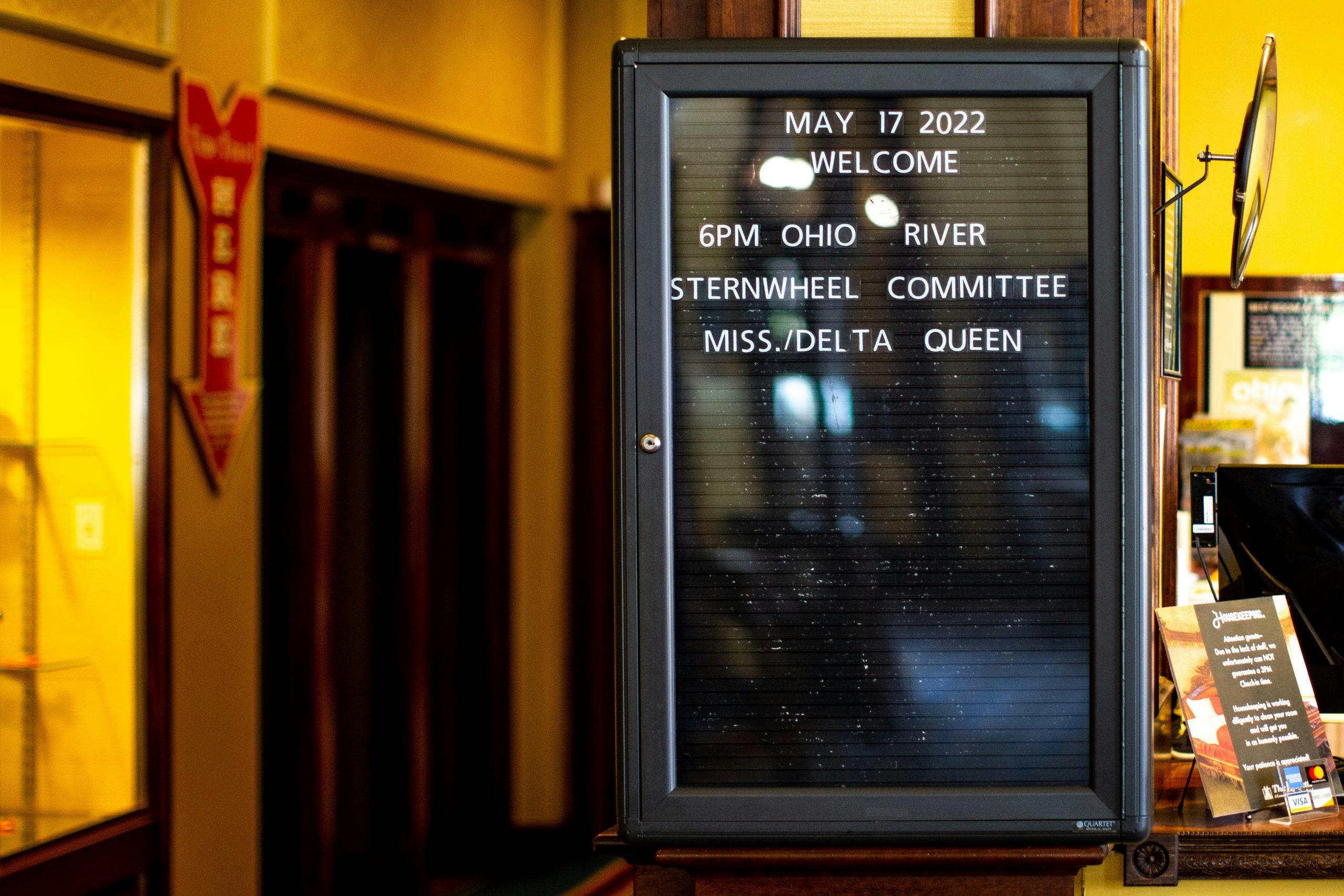

The rain picked up, pelting the vestiges of the old speedway, so I hopped back in the Mustang and took off for Marietta, Ohio. I planned to stay at the Lafayette Hotel on Webster’s recommendation. “The place floods a bunch because it’s right on the Ohio River,” he said. “Old and musty. It’s great.”

Indeed, Lafayette smelled like grandmother’s basement and was just as cozy. I took the cabin room, which was the size of a water closet and featured ornate, hand-carved wooden furniture as well as oxblood tile in the bathroom. At the hotel bar I met Steve Simpson, an engineer from Milford, Michigan, who helped develop the 1984 Corvette. Much like the Fox-body Mustang, the Corvette enjoyed dramatic improvement throughout the ’80s; by the time the ZR-1 rolled out in 1990, the C4 Vette was a dagger.

Simpson and his group of boomer buddies had just retired from a day of riding the curves of Southeast Ohio. They were now bellied up to a bar, trading stories about love and loss. “Even a blind hog finds an acorn once in a while,” said one of Simpson’s buddies, showing the group an iPhone photo of a love interest. Sleep that night, which doves cooing in eaves outside my window helped invite, felt well-earned.

Tuesday—my final day in the Mustang. I liked it enough to not care that it burned oil and refused to charge my phone through the cigarette lighter. I planned to visit the Peoples Mortuary Museum in the morning, but after dialing up the number on the back of the pamphlet, I was informed that the museum was closed on Mondays. Even death needs a day off.

I traveled north on I-77. Rather than make a highway haul like I had done the day before, I took an impromptu exit and tore off into the wealth of tight corners and steep drops. The Mustang is poised on the road, especially for its age. The short wheelbase and humble track width were ideal for the squirming roads of Southeast Ohio. The rear end gently pivots through long corners and the body roll is relatively minimal. From the driver’s seat, the car feels like a compact by today’s standards. Compared to this old Fox, a 2022 Mustang is a leviathan.

I arrived home that evening, having covered more than 700 miles from Winston-Salem to Ann Arbor. The wound of losing all those photos was healing over. I had made a bounty of new memories, anyway. Will what my camera captured present the same way when I come back to this webpage in a decade? Two decades? Definitely not. But there’s no forgetting what I saw over the hood of that Fox-body, windows down and twin pipes roaring.

Had an 89.5 LX 5.0, and it was a delight: light, adequate everything, great seats, and unencumbered by the nonsense found on today’s cars. The ’97 GT I have now comes close, but I actually prefer the Fox: Icould (and did) drive that car all day long…

I had one the same year, GT drive train under an LX body. Had a problem when the steering went south. The car had a GT sport handling package that I didn’t know about. Took three tries before the mechanic found the right parts.

An epic recap of what sounds like an amazing road trip. I’m fortunate with my “day job” to be able to cover some of the same roads and areas you wrote about, although usually in a rental car. No matter – I find that rental cars handle better anyway, haha! Having recently relocated to the Southwest corner of Virginia, I am find it easy to explore back roads, small towns, and forgotten landmarks like those you documented. Two Lane Therapy, we call it.

Something about those old Ford stereos with their CrO2 and Dolby NR buttons brings back lots of memories.

The Chrome tapes were fi def back in the day for Bryan Adam’s Reckless or Styx Caught in the Act….

Interesting car for sure, but also an interesting perspective on enjoying the scenery and not being as focused on capturing everything through the view finder. Memories in your head are just as (or more) important.

Foxbodies had the styling of a Dodge Omni with a 5.0 put in it. Worst looking Mustang by far. Camaros and Firebirds of the era blow it out of the water as far as styling goes.