Fare to Nowhere: My Checker taxicab trip across America

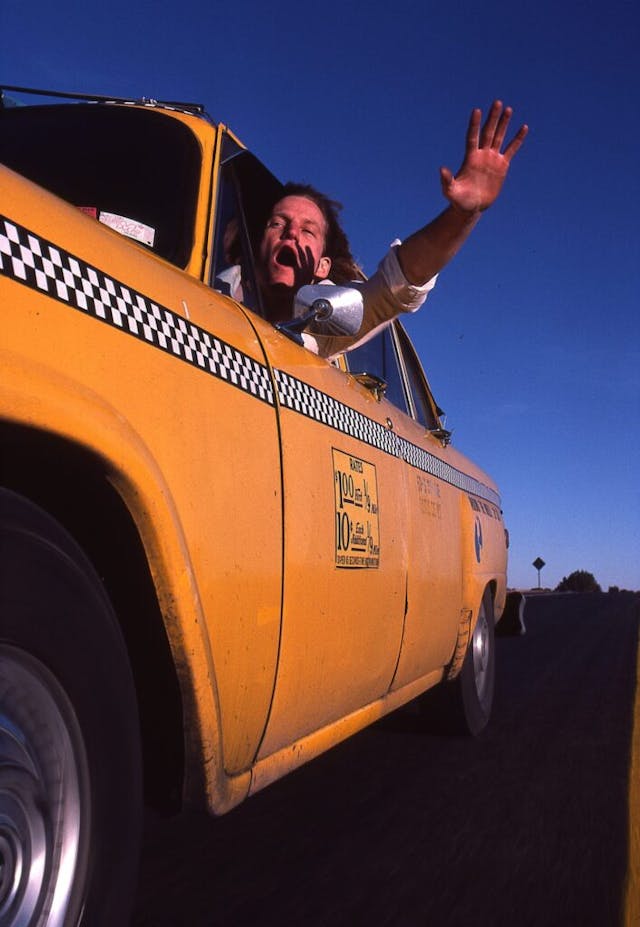

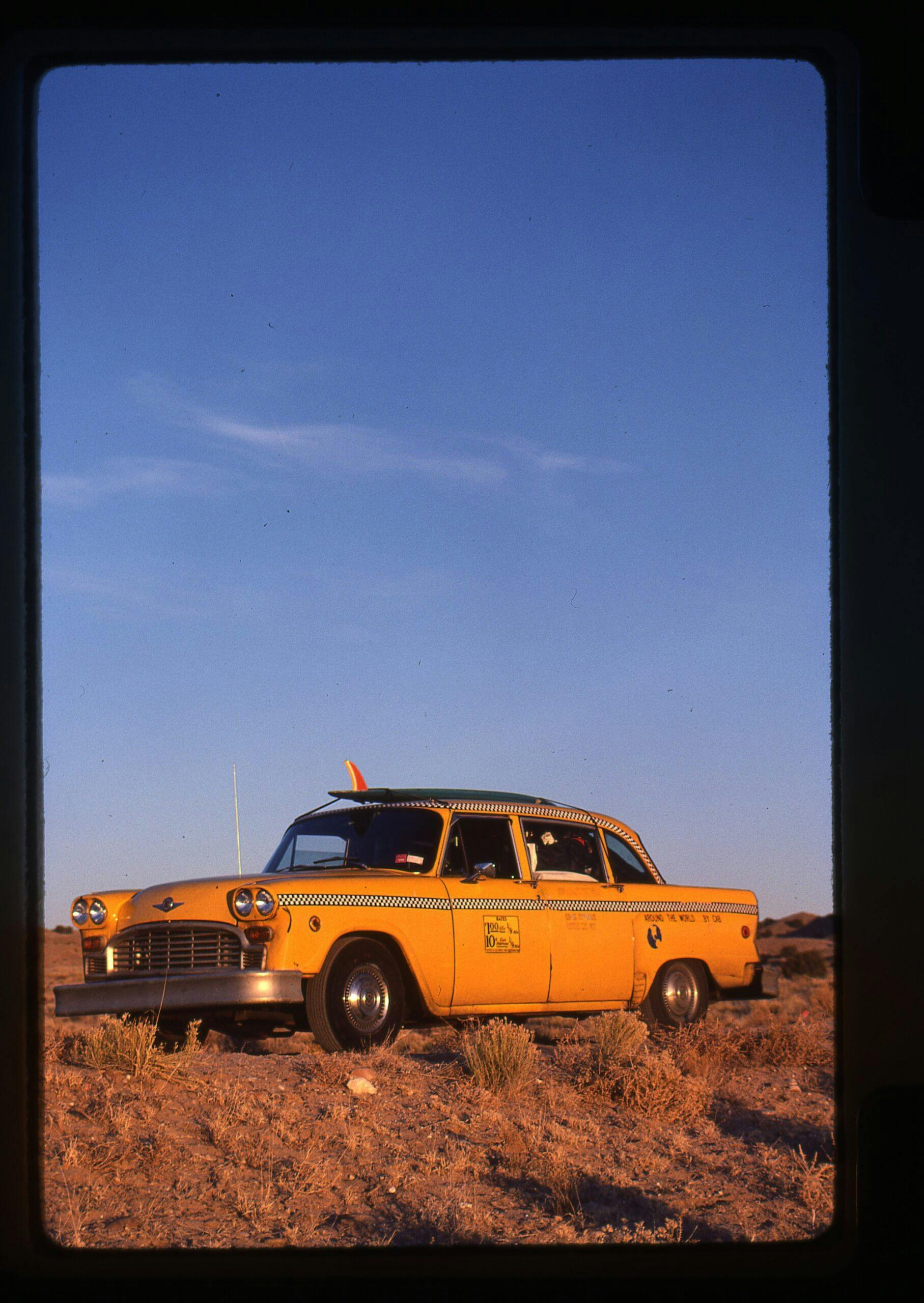

For a young California surfer, the gleaming walls of New York City were all kinds of wrong. Sure, they beckoned like a sparkling Pacific swell in a graceful sine curve of energy wrapping around a rocky point before jacking up and barreling onshore. But Midtown wasn’t Malibu, and in all fairness, I’d guessed the Big Apple would be a weird trip well before I moved there for work, coincidentally on the same day in December 1980 that John Lennon was shot. The city was fun—for a while. Eventually, though, the relentless traffic and sirens, a harsh business climate, and the seething, sweating masses packing every square foot of subways and sidewalks, elevators and offices blew my fuses. Homeward bound, I wished I was. But how? In the city, just one car merited an escape: a Checker cab.

Ernst the cabbie answered the door of his home in Queens. He invited me inside, where the bouquets of linen doilies, shag carpeting, waxed hardwood, and beef stew intertwined in an invisible olfactory waltz. Shortly, Mrs. Cabbie produced two cups of tea whitened with milk and sweeter than a box of Sugar Smacks. Advertised in a local paper, Ernst’s used-up 1976 Checker Taxicab was $800. It was also as large as a moving van, and, most important, it ran.

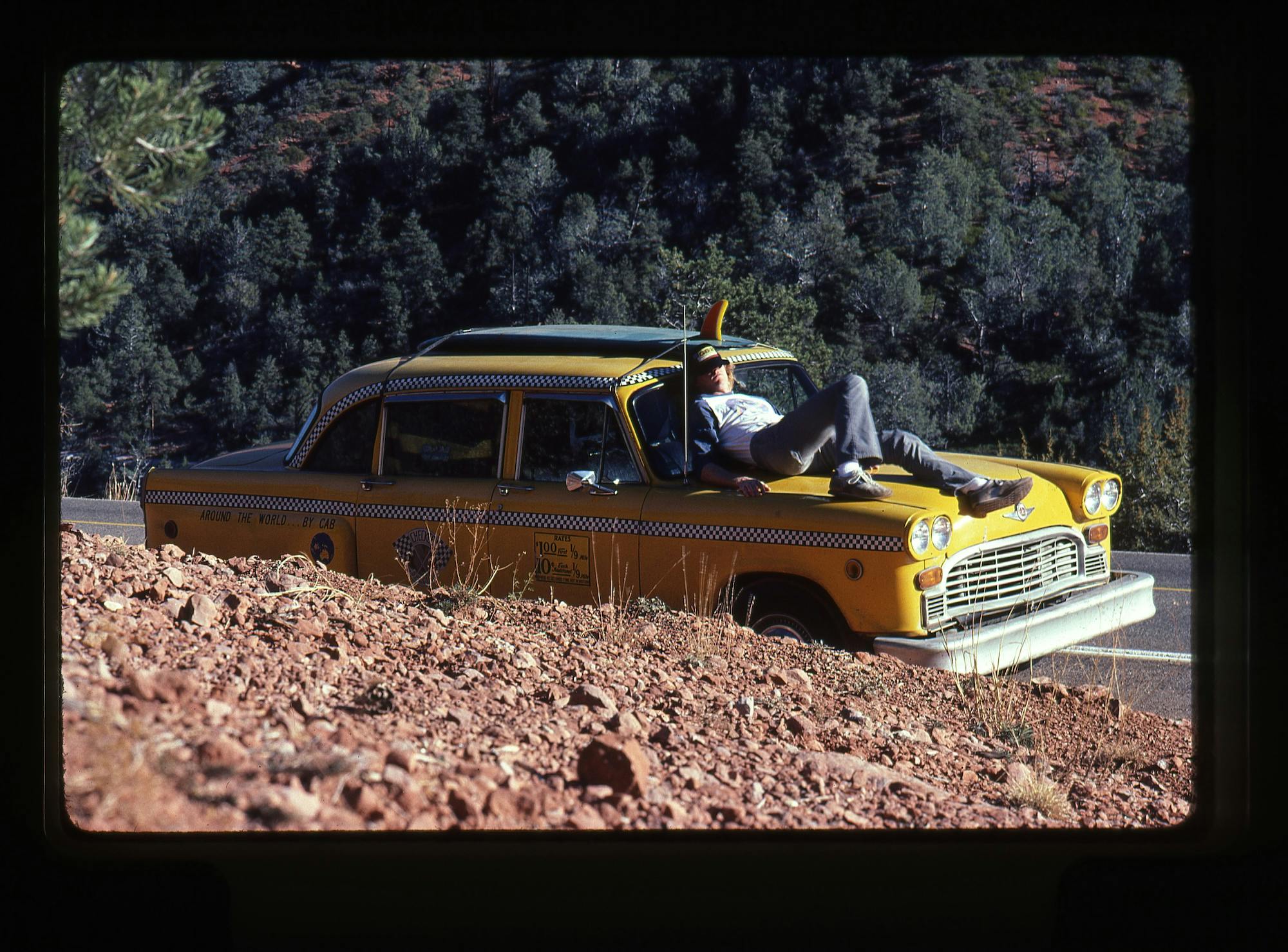

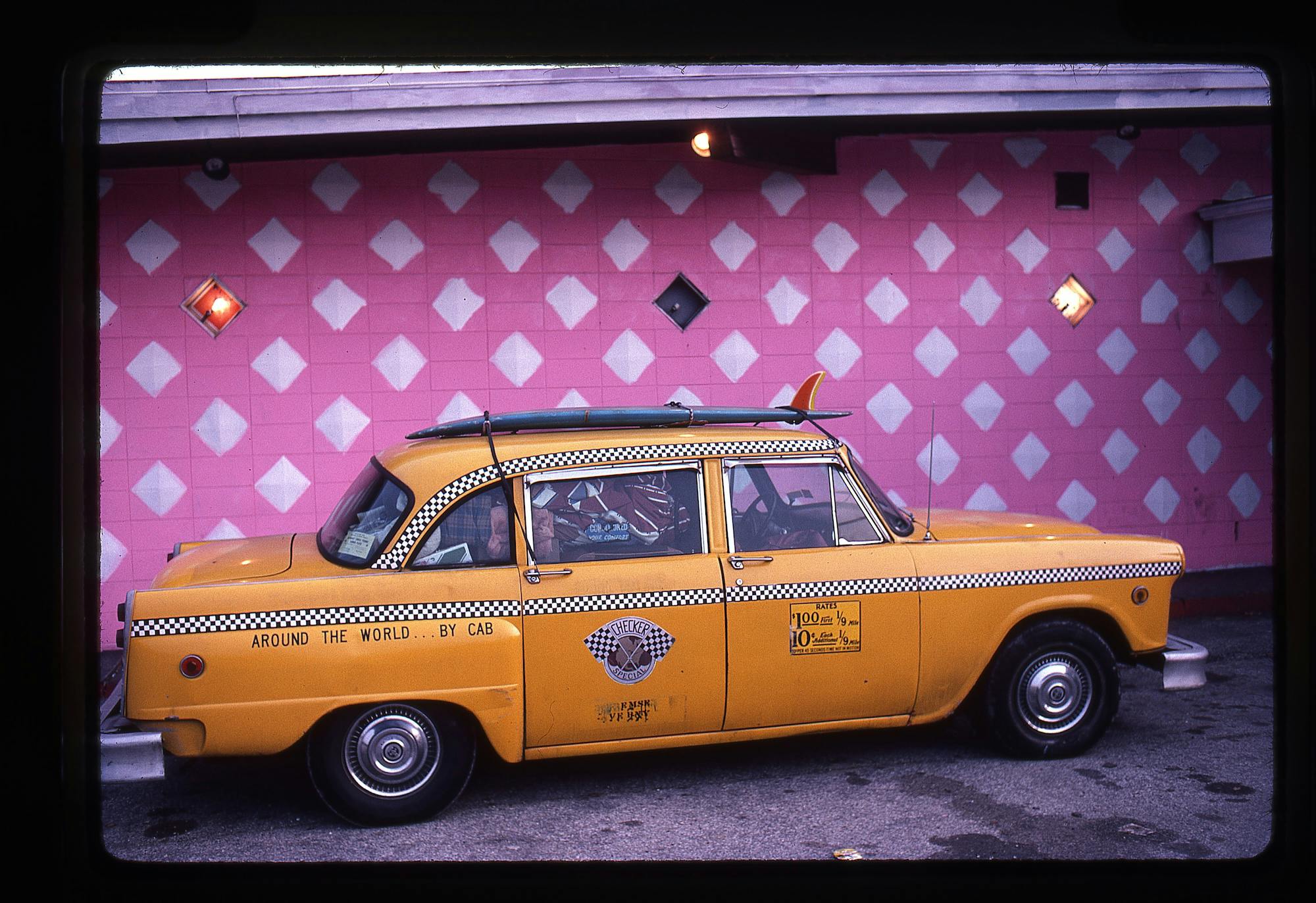

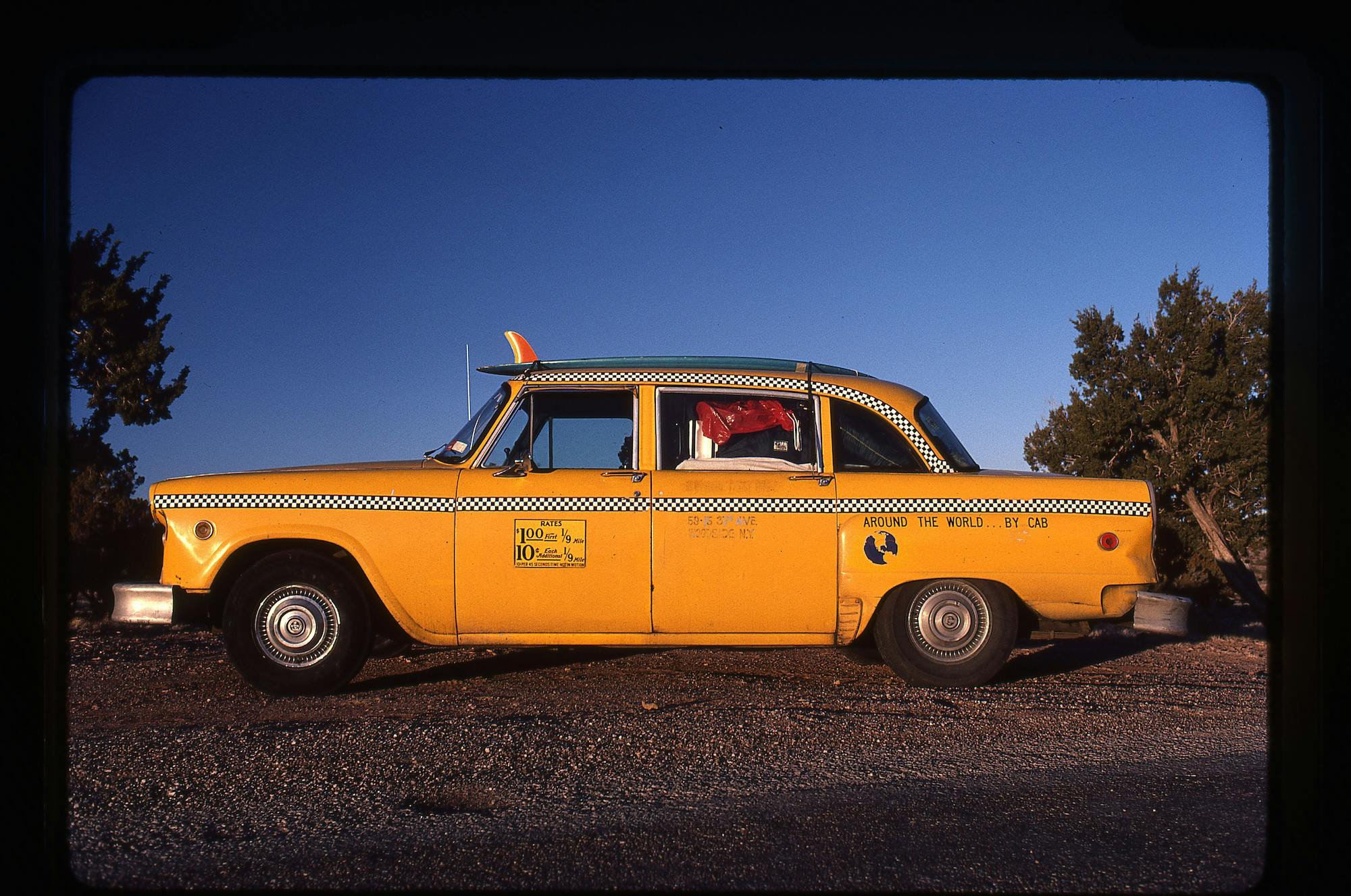

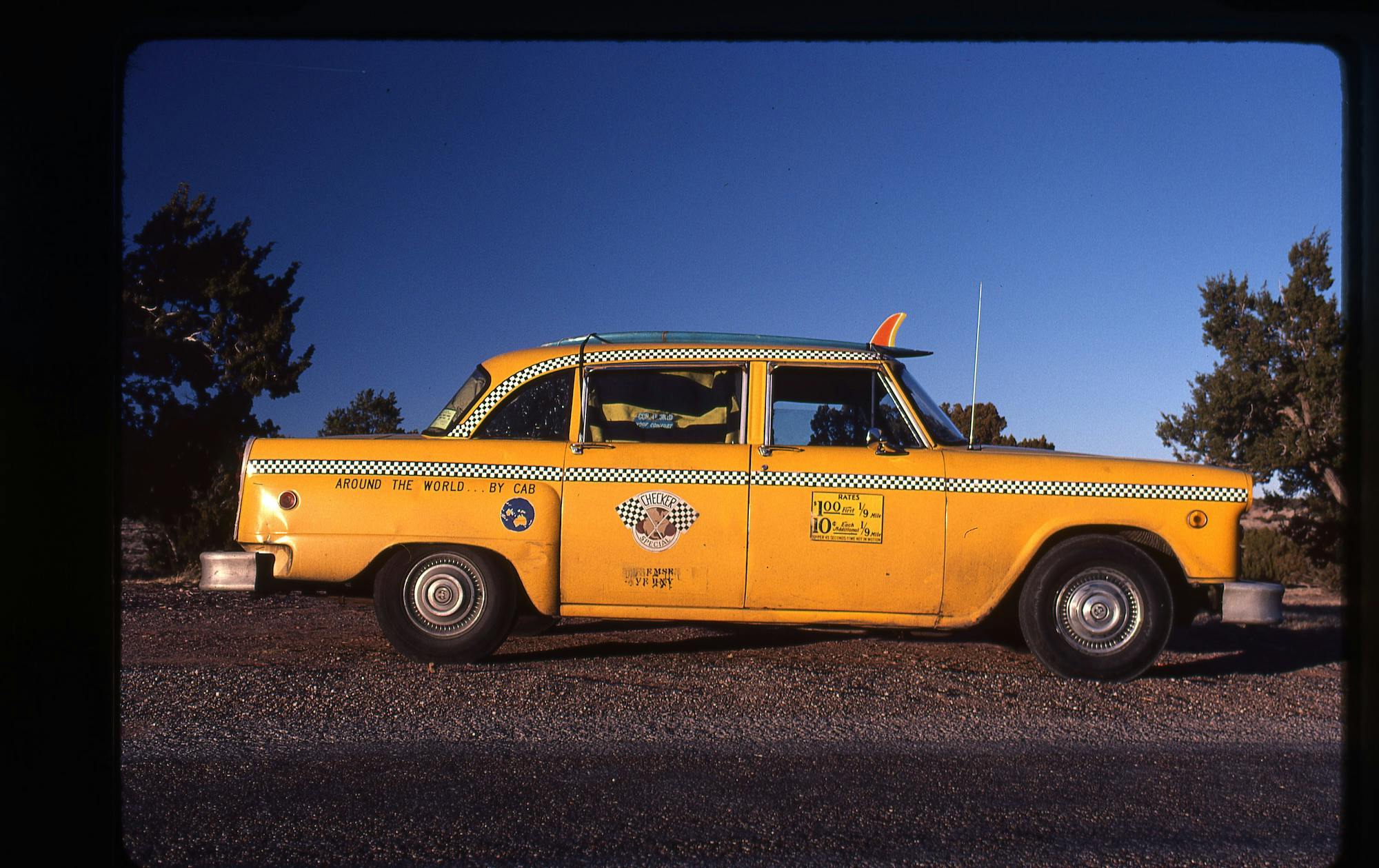

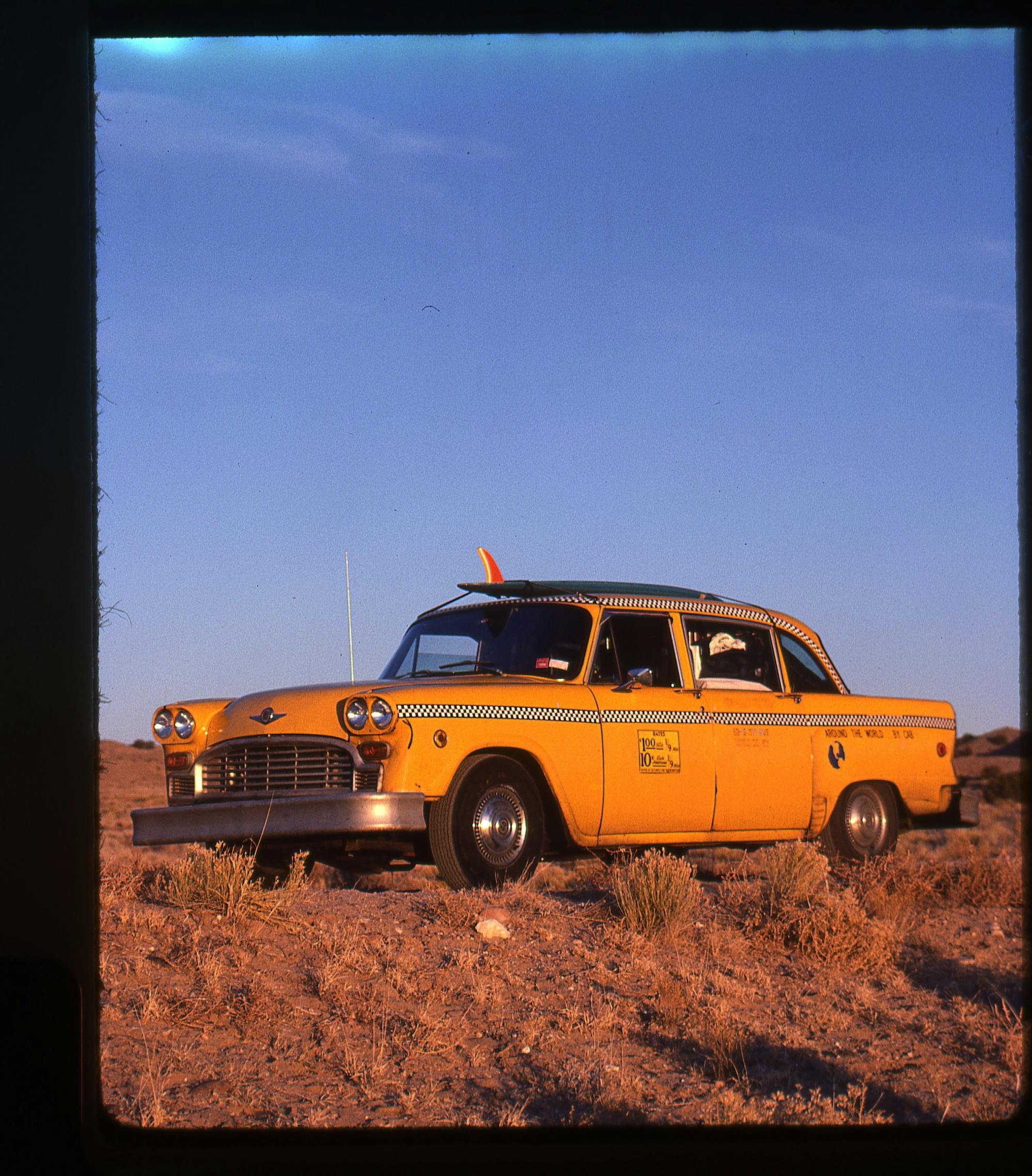

While we talked, the Checker sat curbside looking like a beached, sunburned rorqual awaiting rescue. Its enormous front bumper, which could easily double as a Darlington guardrail, was twisted down as if smashed by Cale Yarborough’s 427 Galaxie during his massive ’65 crash there. The precious “medallion,” New York’s operating permit for cabs, had been prised from the hood, and the roof light and taximeter were likewise switched to Ernst’s new ride. “Rates: $1 First 1/9th Mile,” read the chipped door signage. “10¢ Each Additional 1/9th Mile; 10¢ PER 45 SECONDS—TIME NOT IN MOTION.” Huh. As a passenger, NYC to LA penciled out to $2511.36—not including charges for any delays. Owning looked way better than renting.

Inside was purposefully banal decor, including black vinyl bench seats front and rear, shabby rubber floor mats, and a pair of swing-up jump seats. Separating the quarterdeck from steerage, a bully-proof, bulletproof, Life-Guard clear partition spanned the cabin, with a pass-through for cash located below. “For our families’ peace of mind,” promised a 1976 Checker brochure; in 1981, when this tale happened, New York City was rough. Elsewhere were signs of wear and tear, indicating relentless use over the car’s six years of servitude in America’s biggest burg. Ernst added that he had shared it with his son, each driving 12-hour shifts so the car literally had zero downtime.

The Checker Motors Model A-11 Taxicab debuted in 1961 and was built in Kalamazoo, Michigan, until production shuttered in 1982. This one listed for $5274.54 and featured the base 250-cubic-inch GM inline-six engine backed by a robust Turbo-Hydra-Matic 400, all nestled inside a cavernous engine bay and X-braced ladder frame with a breathy 120-inch wheelbase. It was equal parts Sherman tank and stagecoach and built for hard work. Get this: In 1999, the last New York City Checker Taxicab finally retired, a 1978 model with nearly a million miles on the clock from hacking through nearly 4000 miles of city traffic per month continuously for 21 straight years. Insanity.

Who knew how many times my new ride’s odometer had rolled over, but on November 24, 1981, it read 54,170 miles as the cab navigated toward the apartment of a young lass I’d met at an Upper East Side party. She needed a lift to Wisconsin for Thanksgiving, and since that was reasonably en route to good surf, I’d offered her the right seat. Paula must’ve had a screw loose to trust what was heading her way on that cool, clear Tuesday. Rattling across Midtown, its suspension juddering and body shell booming whenever the tires slammed a pothole, the bandit cab must have been a sight.

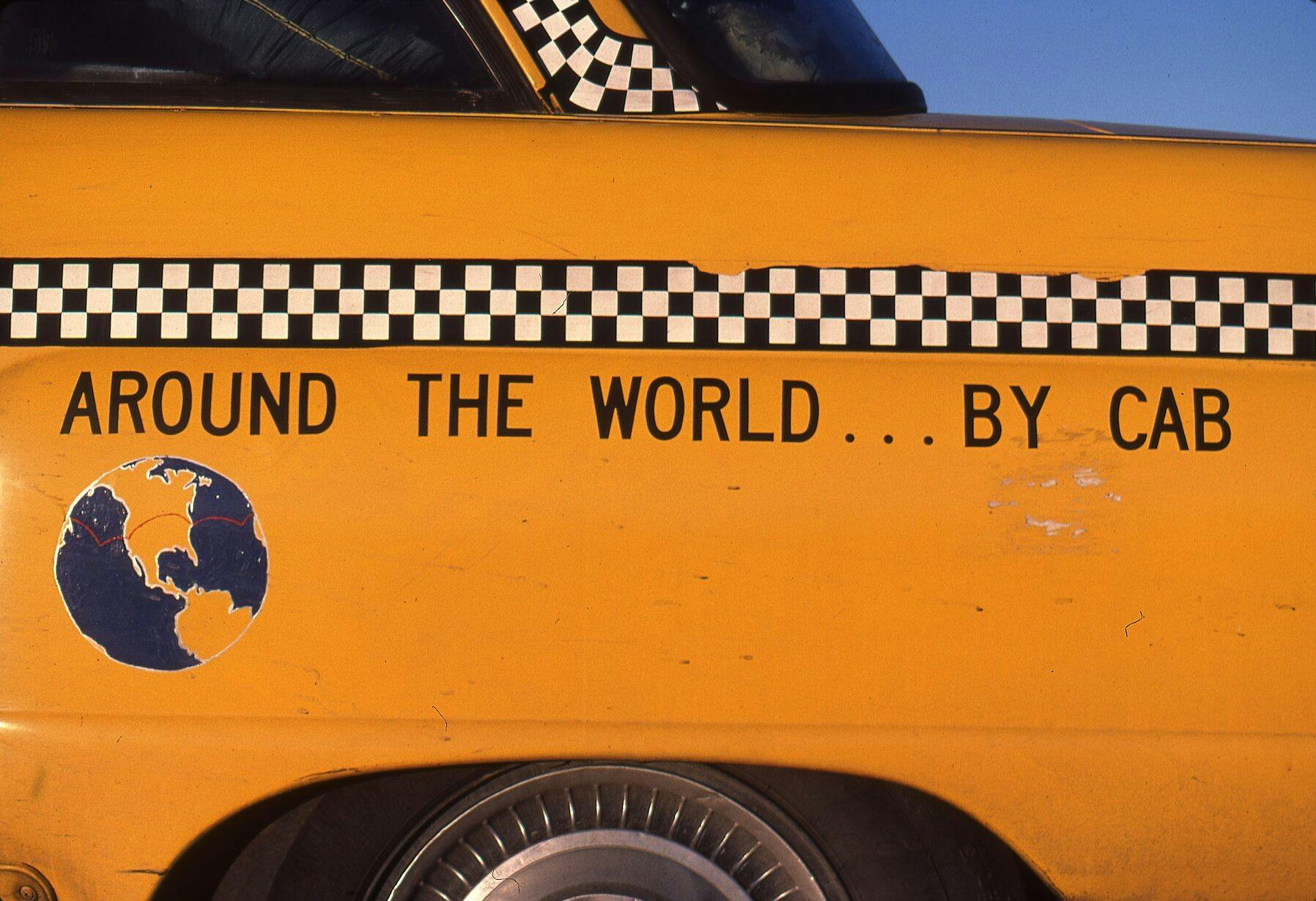

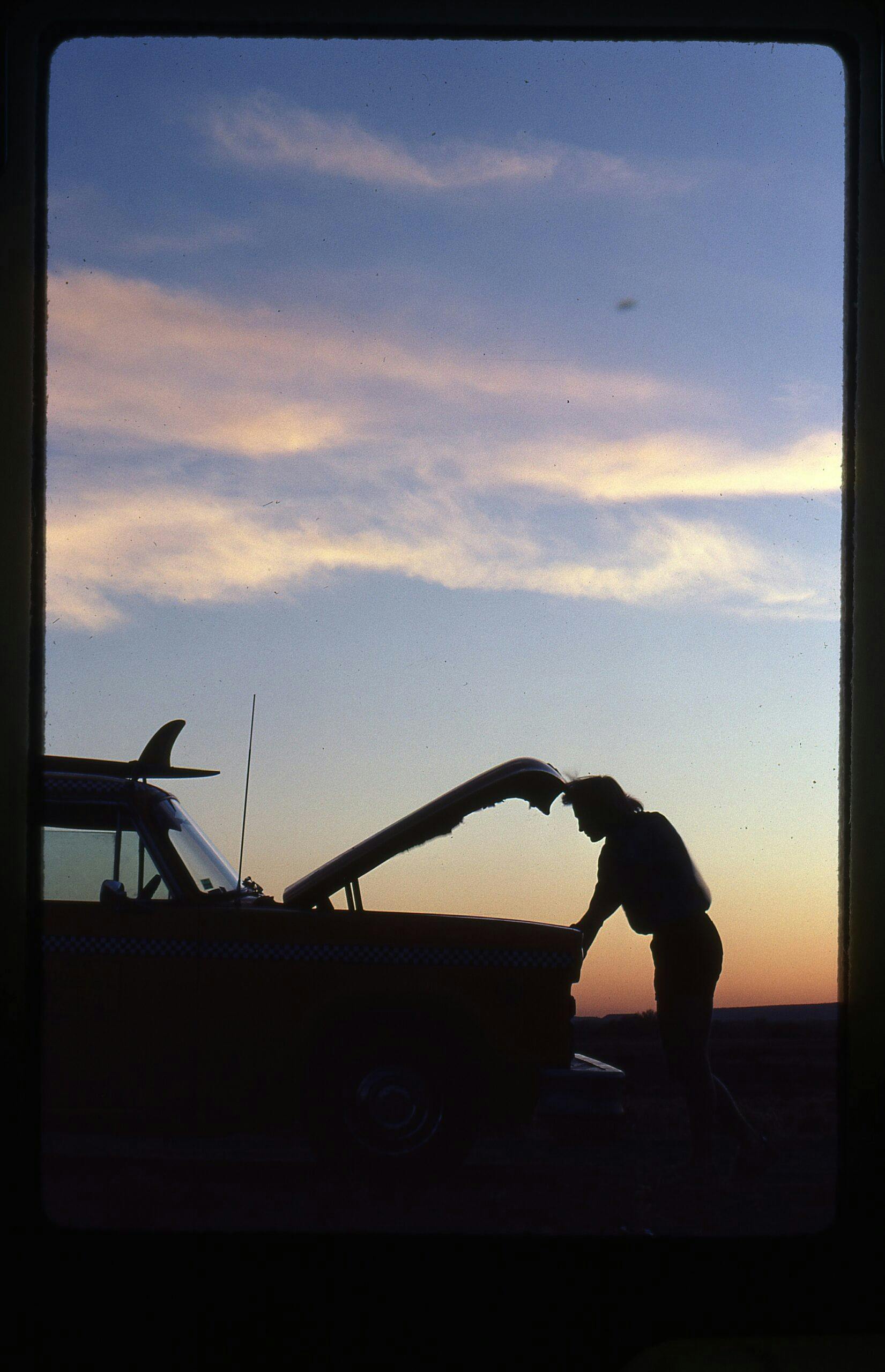

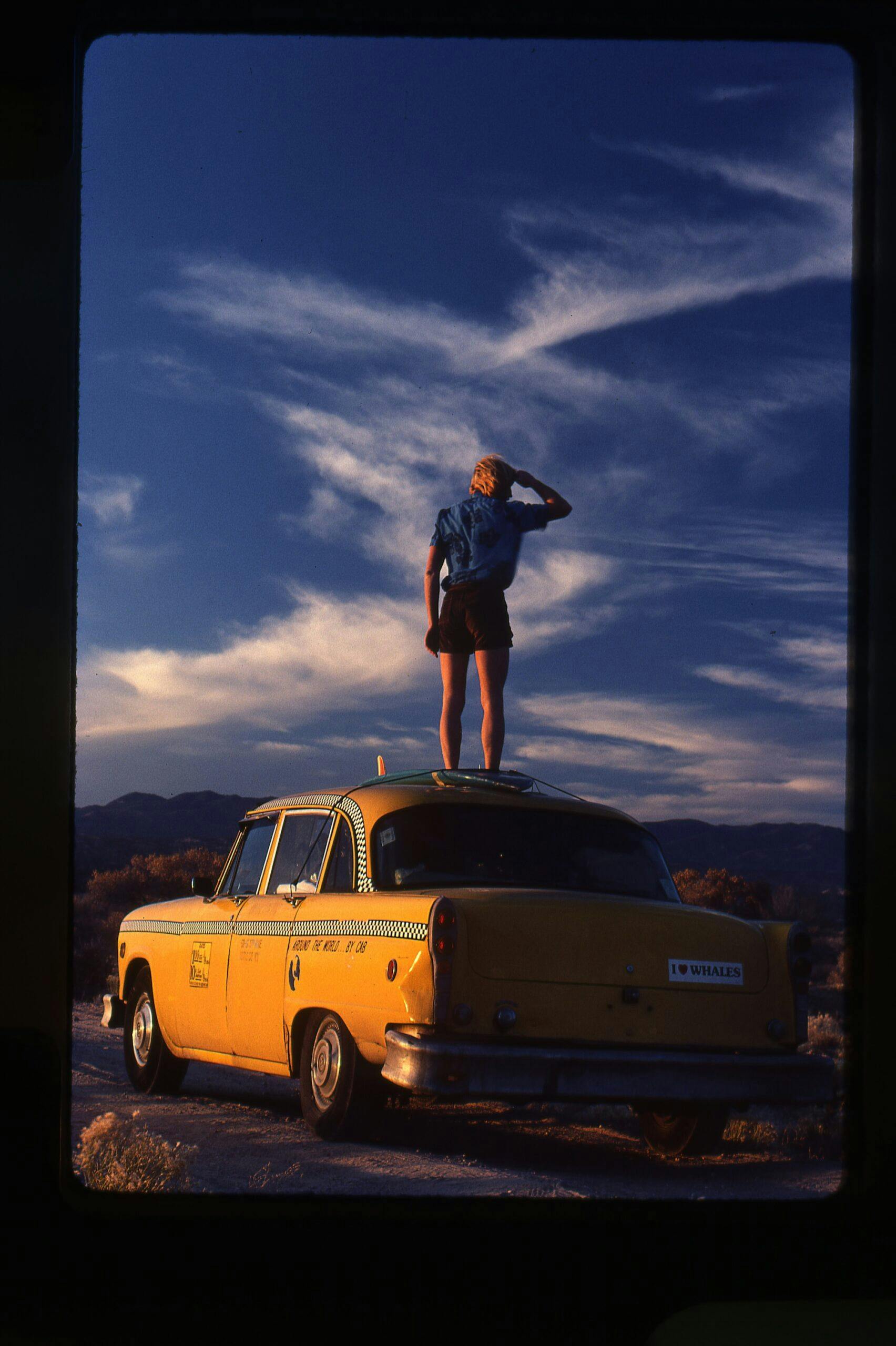

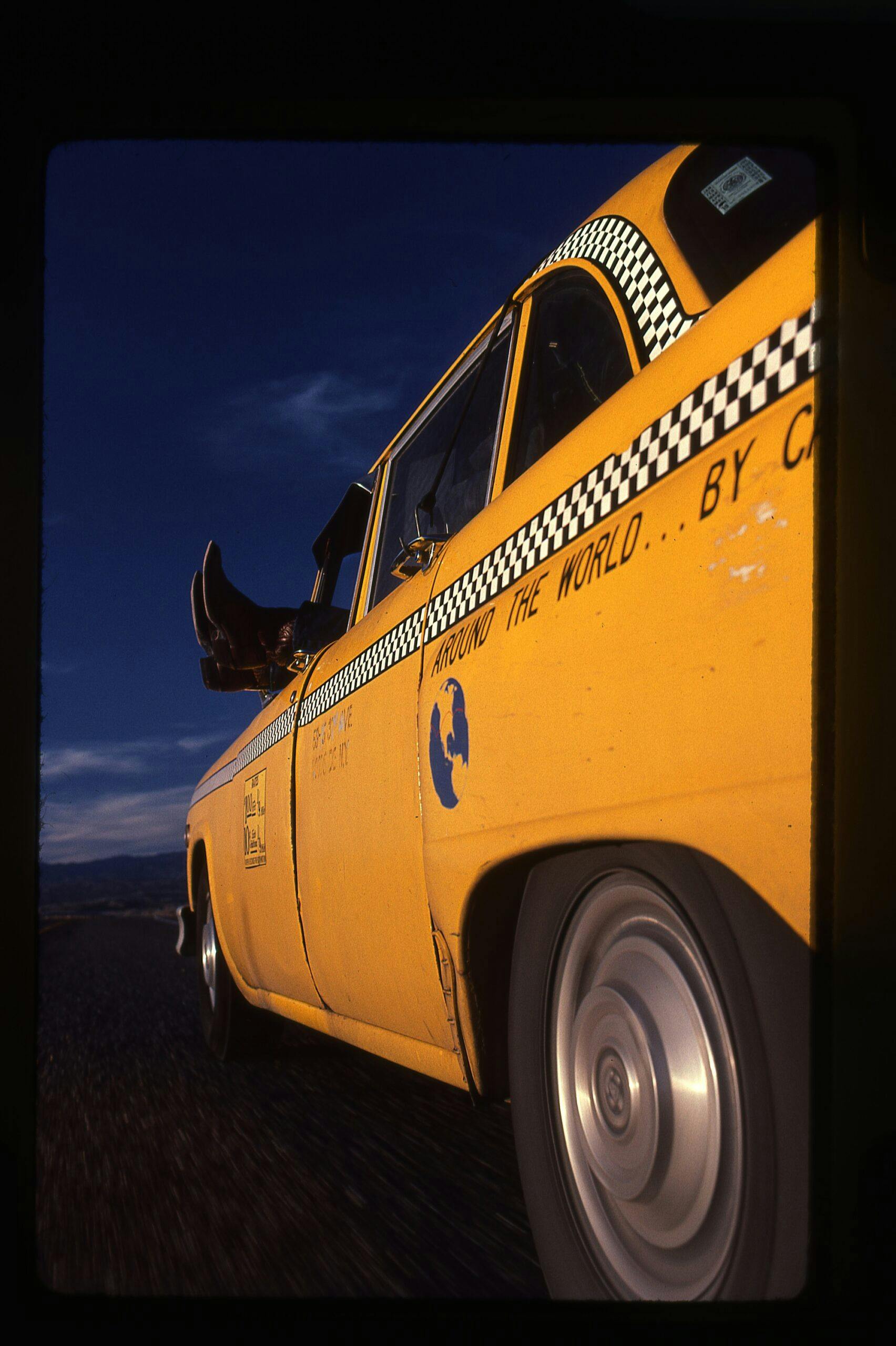

Literally, because I’d stuffed all but one of my possessions inside, right up to the ceiling, while lashed to the roof with trucking bungees was my surfboard. To mess with folks, I lettered “AROUND THE WORLD…BY CAB” on the rear fenders and slapped an “I LOVE WHALES” sticker on the trunklid. I’d unwittingly created a freak show with me as the star, but I really didn’t care; this was the starting line for adventure.

Frankly, it made no sense to leave my highest paying and possibly best career-starting job yet for such a wretched, reckless, and temporary ride. I had been working as senior editor at Adventure Travel magazine, right next to offices for Car and Driver, Flying, Cycle, etc., in the old Ziff-Davis headquarters on Park Avenue. When I reconsider it now, the trip—and, moreover, my about-face to the West Coast—was purely instinctual, driven by youthful myopia, money in the bank, and a congenital disdain for authority. Broadly, Aesop’s “The Wolf and the House Dog” fable called it. In the fable, a fat house dog meets a scrawny wolf and extols his pampered life. Wistful, the hungry wolf nearly signs on, until he spies a worn patch on the dog’s neck where collar and chain attach. “‘What! A chain!’ cried the wolf. And away ran the wolf to the woods.”

Oh, and that last item not packed in the cab? It was my apartment’s telephone, which I discarded on the sidewalk nearby. Don’t call me, New York, I’ll call you.

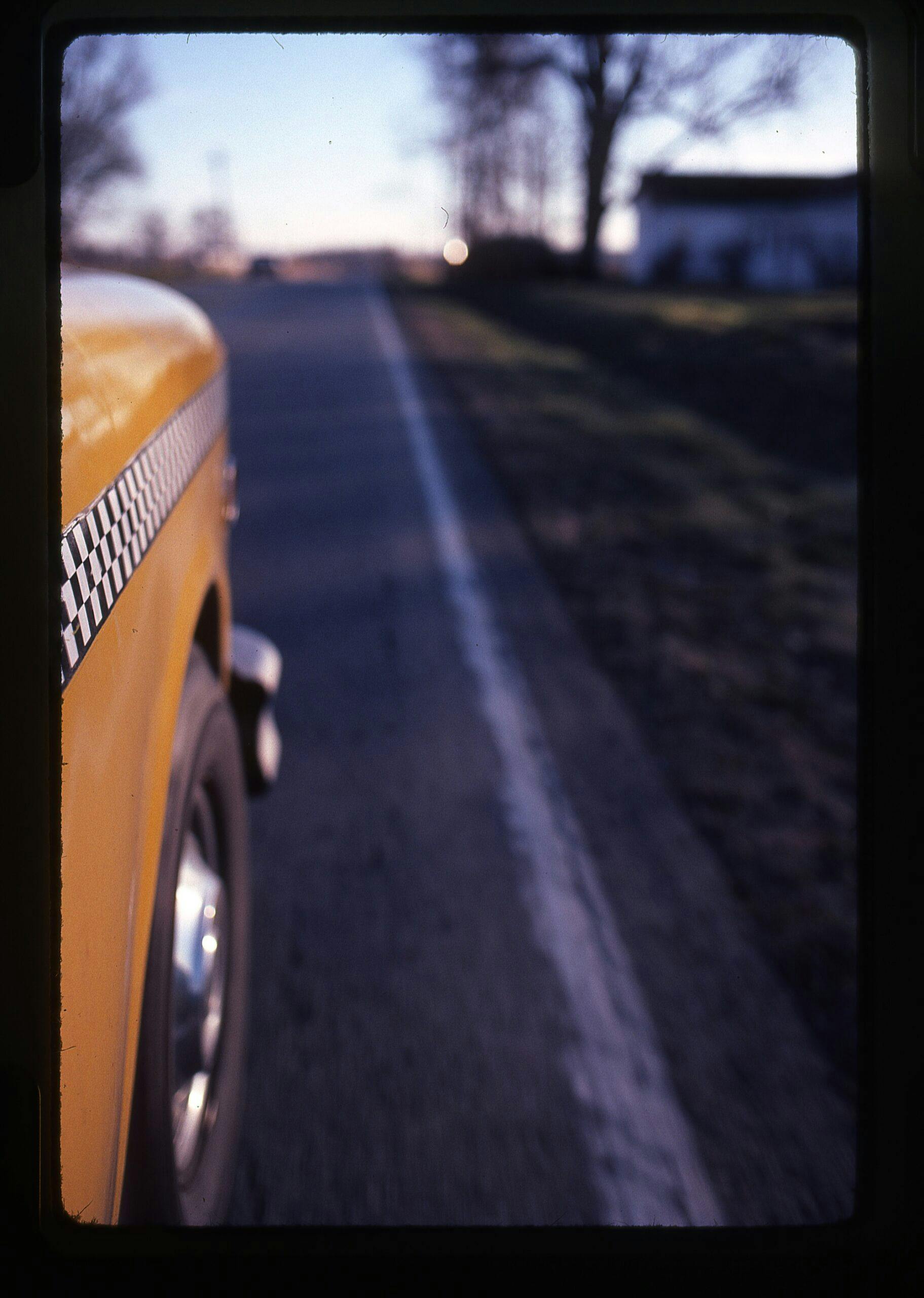

The old Checker certainly did run well, so I didn’t worry about the powertrain. What troubled me was whether the bulging retreads could withstand nearly 3000 highway miles with the car loaded to capacity, and how it would all work on the open road. Luckily, Paula didn’t mind the creaky, shuffling gait; she even wanted to drive. Trading places in the afternoon, her smooth hands explored the wheel delicately, and her unfreckled complexion was softly backlit by the low sun, which refracted through a garnet ring into dozens of miniature green streaks. We made Cleveland by nightfall.

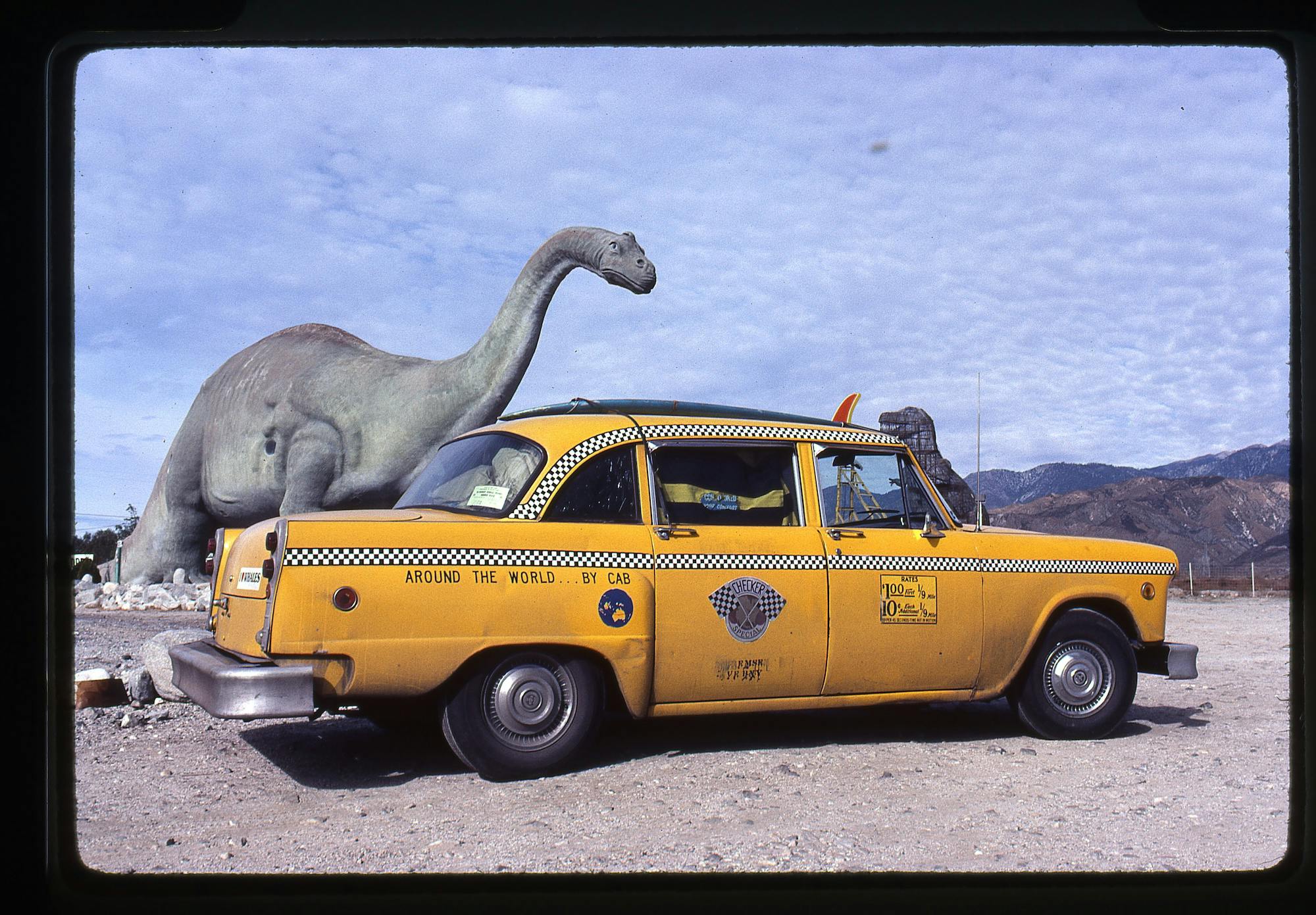

While hoofing west toward Lake Michigan, like a horse sensing its stable, the cab suddenly—well, OK, figuratively—pulled hard right into Kalamazoo, Michigan, its hometown. It was a gray Wednesday before Thanksgiving, dark and bleak as befitting the Midwest. Six miles off I-94, there stood the dingy water tower and headquarters of Checker Motors Corp., then winding down production of cars. “Checker Motors rises out of the murk like a dinosaur from a swamp forest,” I scrawled in the logbook. “Weeds choke the executives’ parking places, and across the road, multicolored shapes sit, awaiting sale or delivery.” I’d bought the car as a tool, but spontaneously visiting this troubled place was like seeing the Chicxulub crater in the Yucatán, the impact point of the asteroid that doomed the Mesozoic era. Within a year, Checker would also be extinct as an automaker, except this time obsolescence was the asteroid. The old triceratops just couldn’t adapt to the times.

Even so, it was a good run for an independently owned specialty automaker. The company began in 1922, when Morris Markin, a Russian immigrant, merged struggling Commonwealth Motors with the Chicago taxi fleet. Postwar, Checker Motors’ forte was building taxis for New York City and, naturally, Chicago. The iconic quad-headlight design we all know launched in 1959 and flourished for over two decades.

An estimated 4000 to 5000 were manufactured annually, including the Marathon model for families, a station wagon, an executive limousine, and two extended “Aerobus” airport limos. A more upscale taxi, if you’ll pardon the term, was the A-11E, which featured a 9-inches-longer wheelbase and rear doors, a standard 350-cubic-inch GM V-8, and optional forward-facing auxiliary seats instead of the side-facing jump seats of this base A-11 model. Today, about 2000 Checker taxis are estimated to have survived.

What had been decent front tires 900 miles ago in New York were flat-out roached when I dropped off Paula and shot down to Chicago to pursue what was left of Route 66. At the time a smarter motorcycle guy than car guy, I didn’t quite know what to make of the tires’ odd wear pattern; mysteriously cupped and bald on the inside. But a Montgomery Ward store had a solution, sort of, and levered on a new G78-15 Runabout Belted and a used Vogue whitewall. Seemed like problem solved.

And then, as Kenneth Grahame wrote in The Wind in the Willows, “Toad, with no one to check his statements or to criticize in an unfriendly spirit, rather let himself go.” Answering to nobody and desiring to make the escape from New York more meaningful, I found a hobby shop and bought some Testors model paint, a brush, and thinner. So equipped, I went to work on the Checker’s body sides, painting a globe featuring the Western Hemisphere on the left and another showing Australasia on the right. Intending to further spoof the general populace, I detailed these with lines showing cities where the cab had allegedly been—or would ultimately visit. “I’m such a clever Toad,” remarked Grahame’s protagonist with conceit.

For all my “cunning” at the time, today the artwork seems dumber than the worst cartoon storyline, but my clumsy choices were just beginning. This I was about to learn as I traded heaven for hell at Chicago O’Hare International Airport, where I picked up high school friend Hunter for companionship on the Mother Road. To illustrate that a blind pig doesn’t always know a truffle when it finds one, consider this: Paula had been smart, sweet, agreeable, engaging, fun, pretty, and more. So naturally, I’d traded her in without cause. Forty years to the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, “Hunt” flew to Chicago to join the drive to LA. He’d come at my urgent request. “Old buds on the loose!” I’d enthused. “On Route 66! In a real taxi!” However, since graduating, he had become a grouch, a whiner, and an accomplished hypochondriac. Bluntly, Hunter was a boil on my backside from the moment he in his puffy orange Eddie Bauer parka with his battered American Tourister suitcase climbed into the cab—which, as if in retribution, still carried the last delicious traces of Paula’s perfume.

Despite his experience as a motorcycle desert racer and explorer, Hunter tired of the ride a mere day into our 10-day plan. “John, your cab is so f****** slow,” he complained from the passenger seat, valuables packed around him like gilded offerings in Tutankhamun’s tomb, including: a wrinkled bag containing a half-eat-en Filet-O-Fish; a Sanka coffee can full of prescription meds; and a formerly white handkerchief, now stained with who-knows-what. On the bridge of his nose perched wire-framed prescription glasses, their broken hinges soldered solid at the temples. “And the miles out here—they’re not normal miles, they’re country miles!”

This point, I had to concede. The Checker was acceptable in the city—coarse, clunky, and cumbersome, maybe, but dammit, the thing worked. At highway speeds, the game changed entirely. Sucking hard through its one-barrel downdraft carb, the thrifty overhead-valve six struggled to keep up with only 105 horsepower. The cab’s blocky shape, which excelled at ferrying passengers and luggage in urban environments, meant aero drag and noise—lots of it. The window seals proved nearly useless, letting the wintry, rushing air in like Jack Nicholson splitting the door open with an ax in The Shining and leering, “Heeere’s Johnny!”

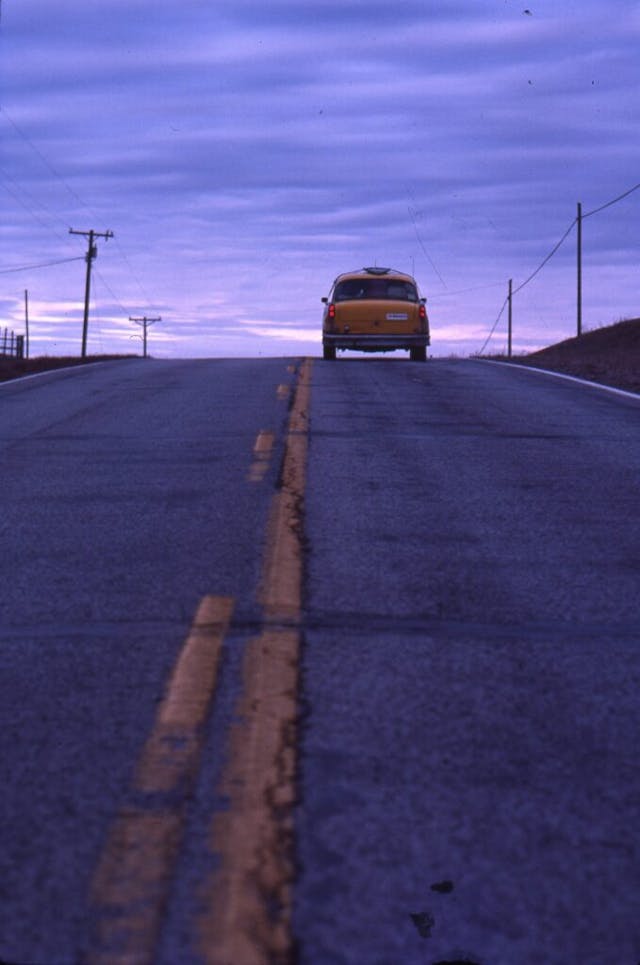

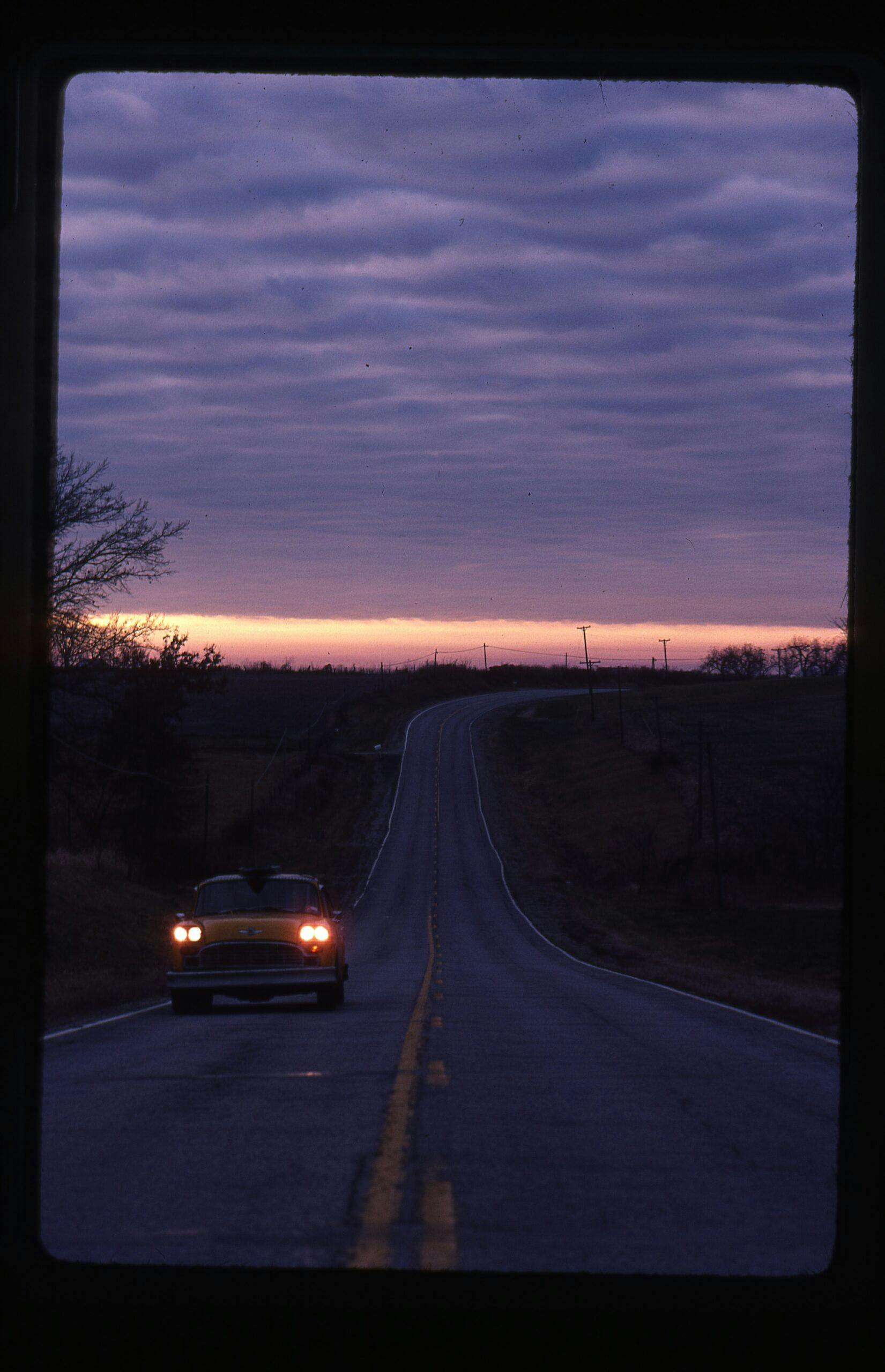

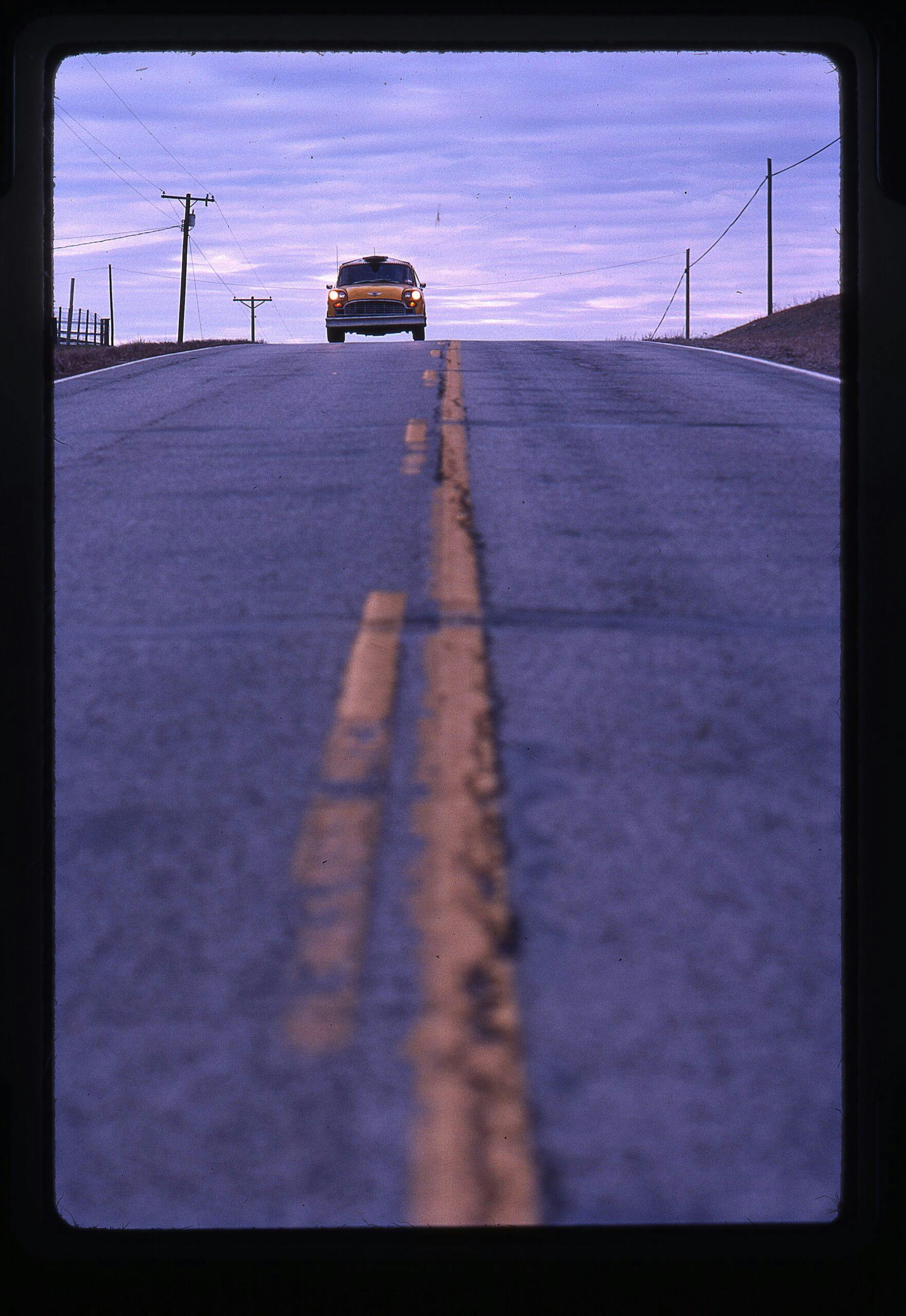

Besides the wheezing engine and arctic blast, the cab also wandered all over the road. At 65 mph, it proved almost impossible to steer straight down its lane. Slowly but surely, over mile after grim, resolute mile, a theory emerged: In the slow lane, where thousands of heavily loaded truck tires had compressed the asphalt, these sunken tracks caught the tread and steered the cab in a drunken, meandering weave. Option A was to slow to 50 mph to lessen the weave; Option B was to merge into the flatter fast lane, which would block real drivers in real cars. Neither was attractive, given the nearly 2000 miles left to go.

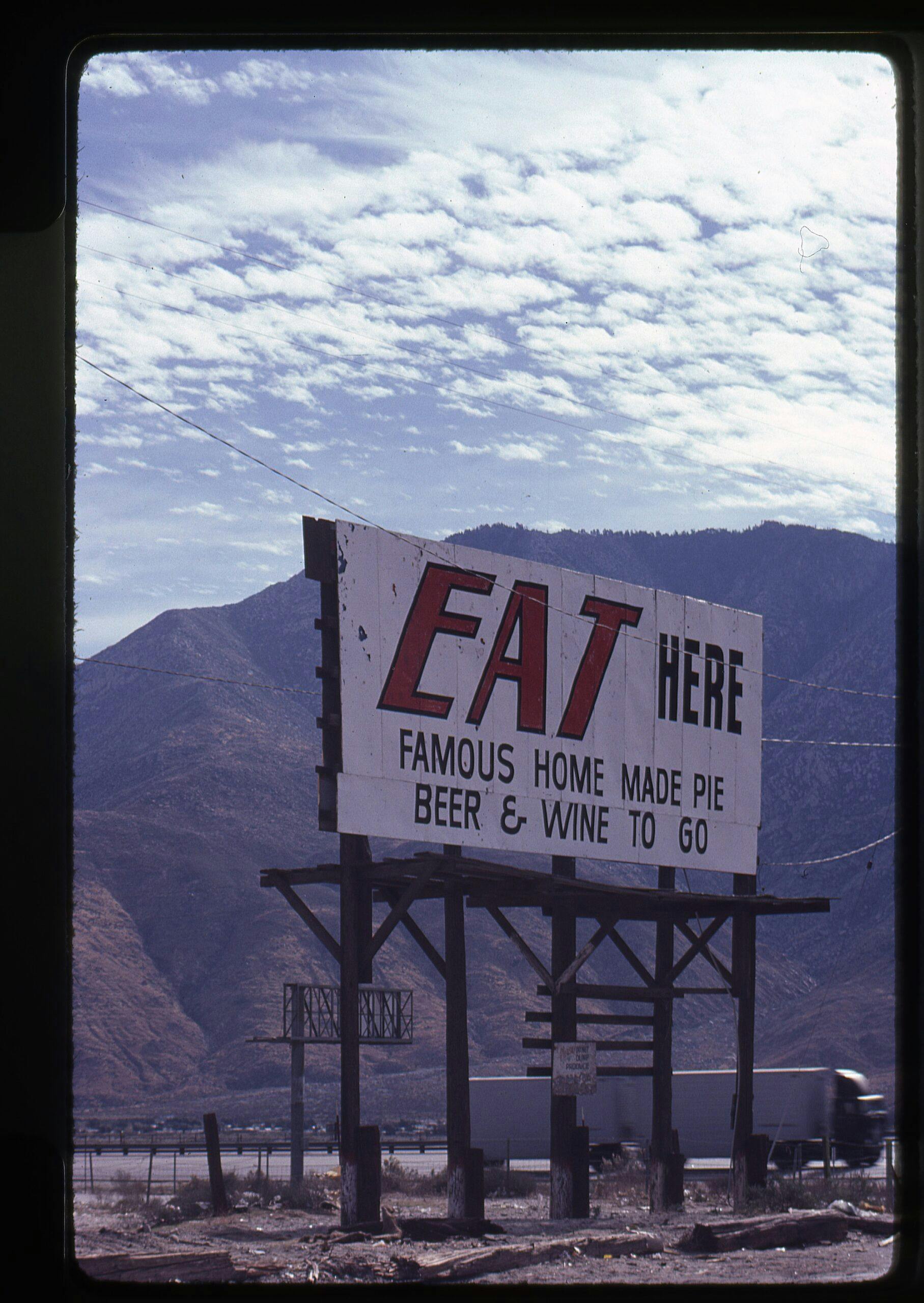

After two days of battling adverse factors (including a stop for no license plate by the Illinois State Police, who released us after seeing the temporary permit), Hunt and I found ourselves nearing Kansas City. By late afternoon, the road, barren trees, and fallow farmland had melded into a dreary gray-brown mud. But above that, the sunset countered with an atomic blast of red, orange, and yellow that ignited the entire horizon. We were pissed at the situation and at each other and, as card-carrying nitwits, decided cocktails and calories would help. Which is why, I suppose, a bright green sign for Houlihan’s Old Place looked so attractive. Like a couple of punchy moths, we bumbled into the parking lot and flitted inside.

“Who’s a Houlihan’s girl? She could be you!” read a period want ad for hostesses there. Well, Marcy wasn’t a hostess, but she was hilarious, into kitsch, and dug the cab—which, gritty from the road, loomed out there in the gloom, like the antichrist of lighthouses. Somehow, she found her way into our booth, and somehow, a few hours later, we found our way into her apartment. Friendly local, check. Need a place to stay, double check. Largish beverage consumption, checkmate.

Hunt had the better instincts, curling up in a blanket on the dining room floor. But elsewhere—was I still heading to hell or already there? In the middle of the night came a loud crash. Hunt had rolled over in his sleep, knocking down a stack of closet doors leaning against the wall and gaining a huge knot on his head. In the morning, we were both happy to be alive and back in the same cab that had caused such misery the day before. Our headaches were the same, but different.

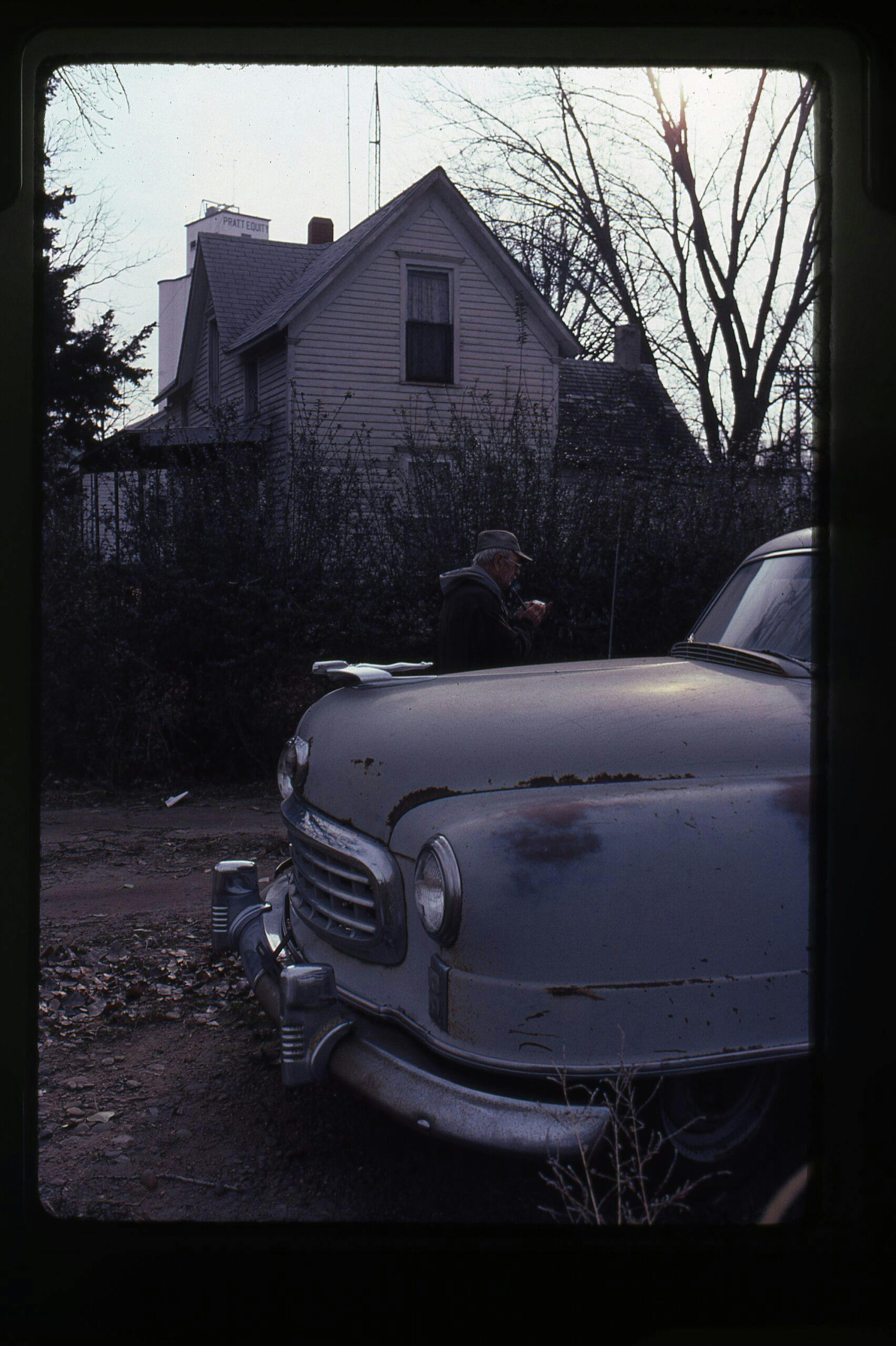

For Hunter the Adventurer, the damage was done. “I’m through,” he said later in Pratt, Kansas. That required only a quick (ahem) 200-mile detour south to Oklahoma City for him to catch a jet home. But hey, anything for a friend. Outside town, evoking Andrew Wyeth’s famous Christina’s World painting, stood an old farmhouse and barn set back from the two-lane, with a “bathtub” Nash Airflyte 600 in the grass nearby. I turned onto a dirt driveway, bounced past a weathered gate, and approached a farmer working near hewn oak doors. He was pushing 80, meaning that he’d been born around 1900. Emaciated, wearing dirty coveralls and smoking a grubby pipe, he meted out praise for Nash’s aerodynamic entry in the “lower-price field.” “Fifteen-hundred dollars,” he croaked. “Runs, too.” Tempting, but nope. (The same money, invested in Apple stock instead, would be worth $2.4 million now.)

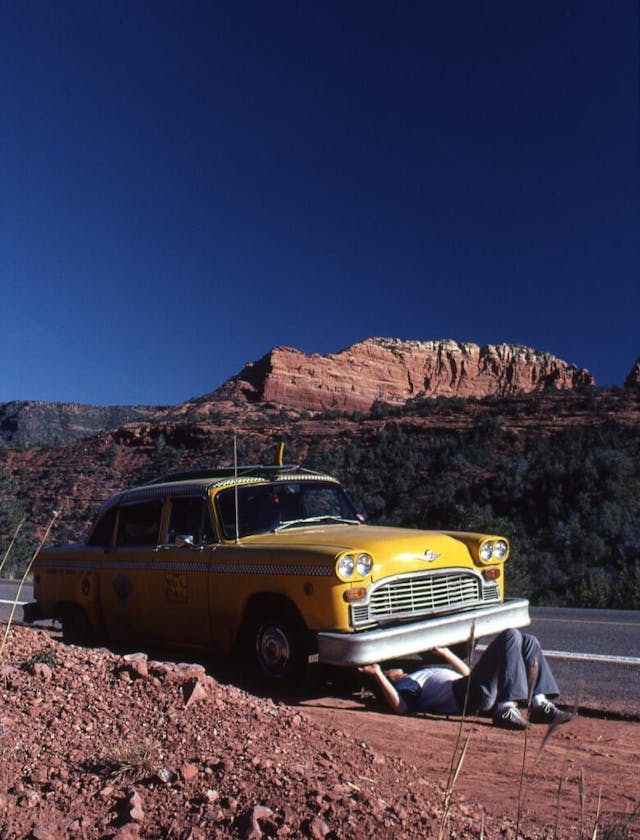

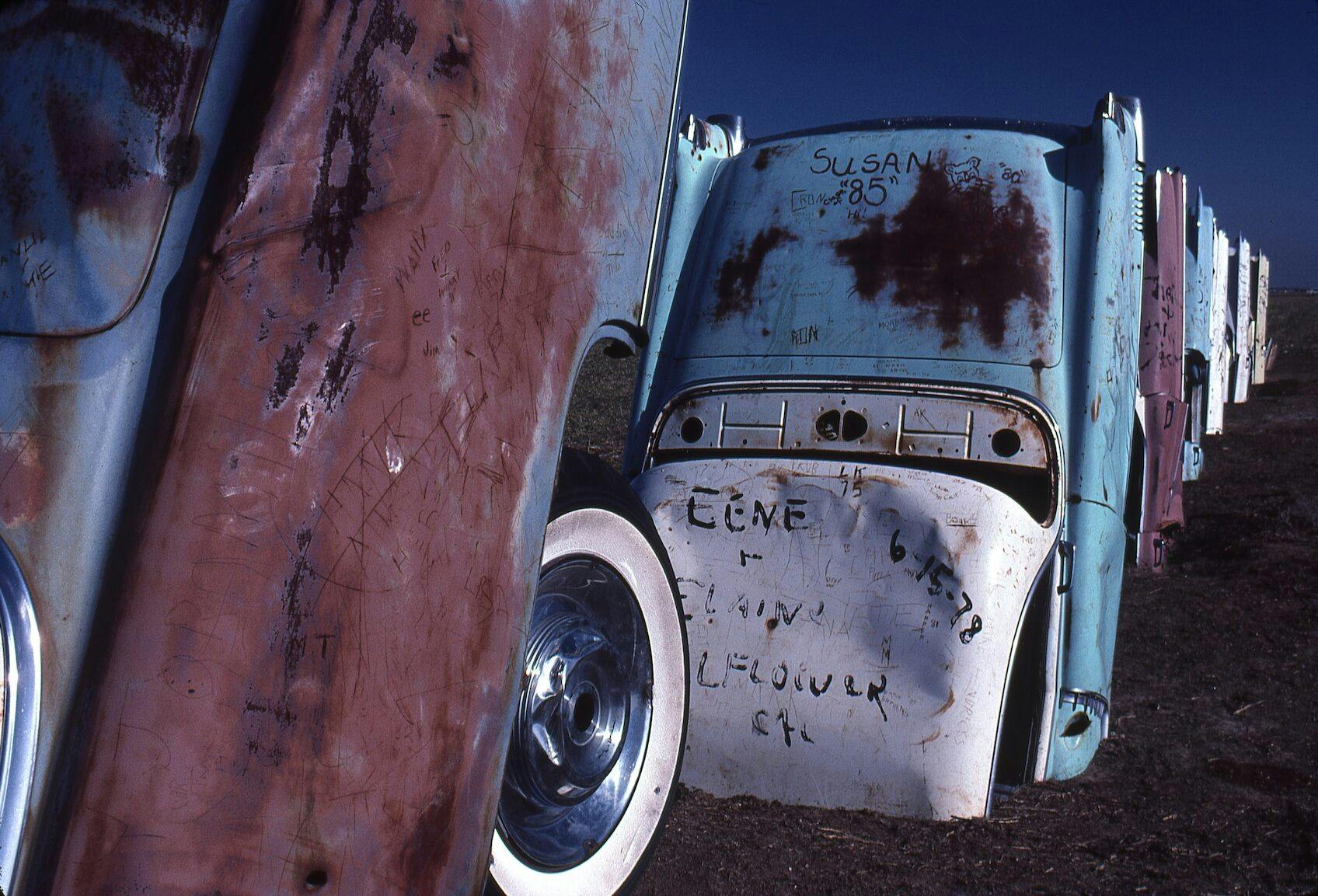

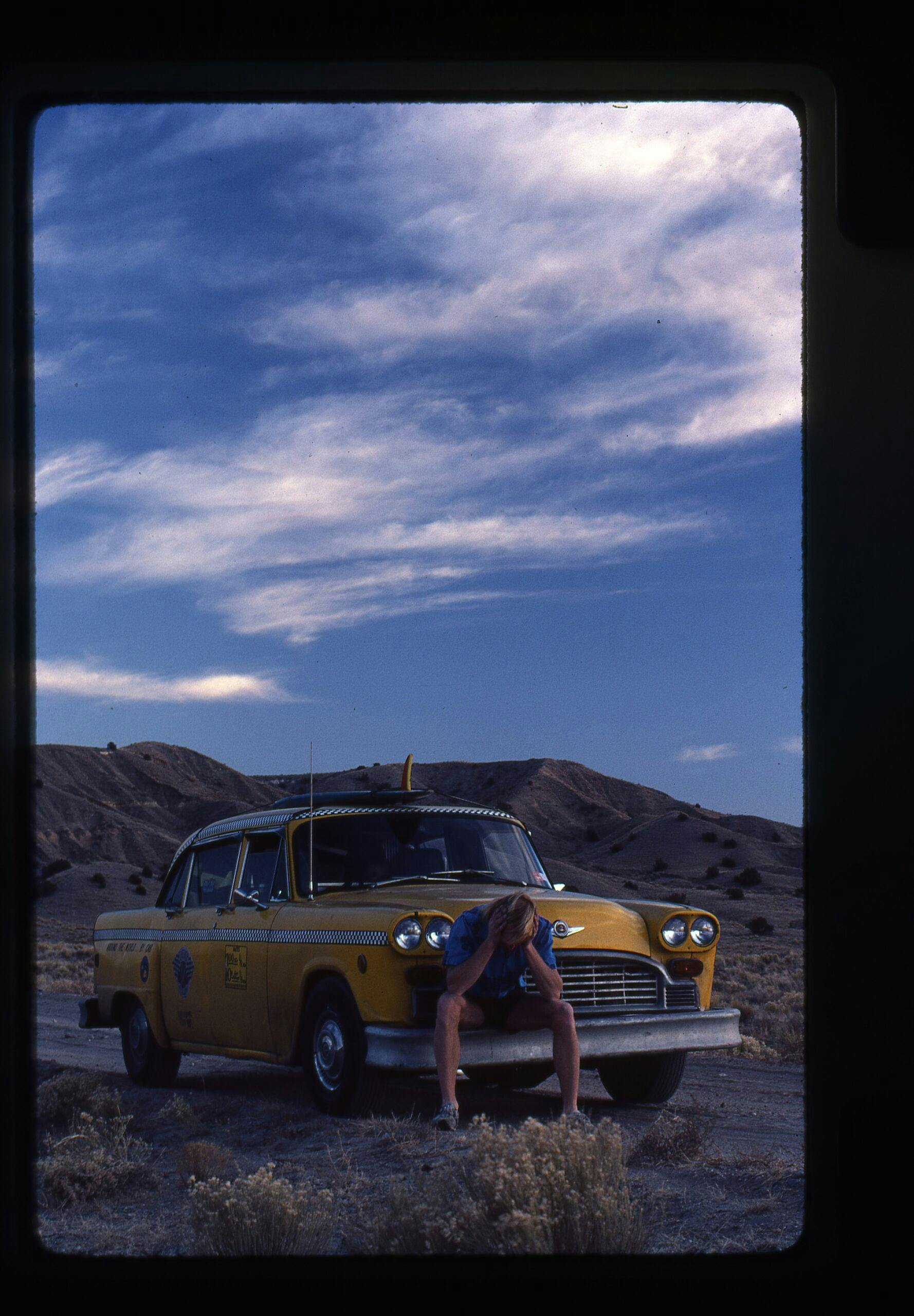

After dispatching Hunter, the Crown Prince Sourpuss, the cab and I wandered up to Tulsa, scouting thrift stores for an imagined $75 Gibson 12-string guitar (no luck) before vectoring toward Cadillac Ranch near Amarillo, Texas. By now almost three weeks into this listless sojourn, I began thinking I’d also had nearly enough. My tail hurt from sitting on the bench seat all day, every day. The engine seemed to be losing power and the chassis’ dynamic hijinks were worsening. Indeed, by Clovis, New Mexico, one of the newly replaced tires had already worn to the cords. The local Ward store lacked replacements, but it had a fine mechanic, who immediately put the Checker on the alignment rack and found the settings to be way off. The old cab had driven toe-out most of the way across the country, causing the scary handling and wear. He worked all morning sorting it out and charged a paltry $13. Across town, a Firestone store had the right rubber, and with those mounted, why, the Checker drove almost like new.

Glen Campbell sang “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” in 1967 and probably had fun doing it. I fared worse, because by the time I got to Santa Fe, loneliness had crept inside the Checker and grabbed me by the gut. How needy can you get? So far, I’d enjoyed a cantankerous best friend, encountered several curious cops, chitchatted with gas jocks, clerks, and waitresses, been kicked off Pueblo tribal land, met some women, and forged deep bonds with tire shops in Illinois and New Mexico.

You might guess that was ample company. Nonetheless, in Santa Fe I went looking for one more soul to share the remaining push to the coast. Anyone with a pulse would do. Apparently, in the rush for personal freedom, I’d failed to consider the value of personal relationships. No luck, though I did wander into a dealership selling brand-new DeLoreans, next to which the Checker looked like a Super Chief locomotive beside tins of sardines.

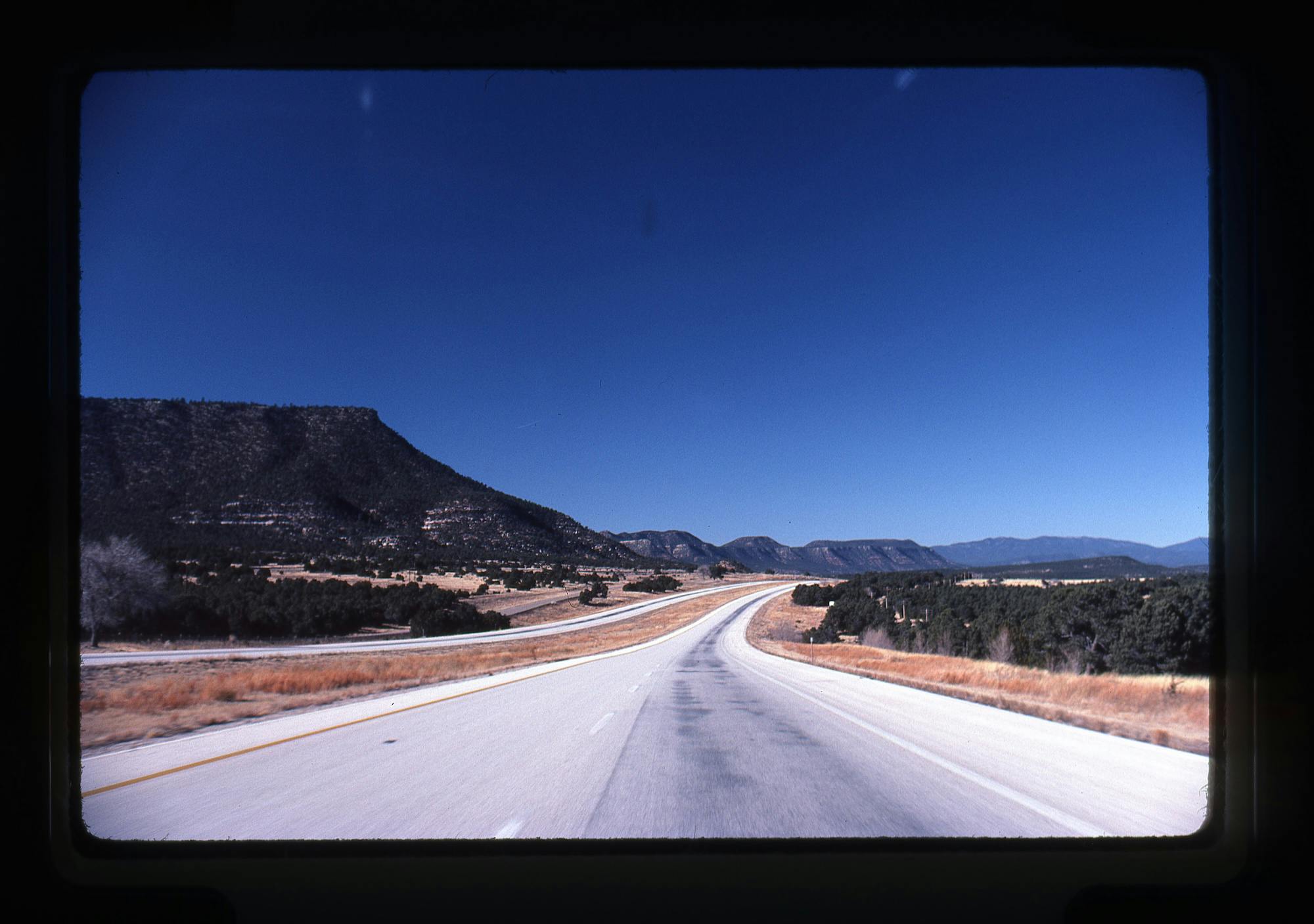

Nearing Flagstaff, Arizona, the reddish tones and sinewy shapes of vaulted sedimentary rock formations, the hardy green junipers, and the clear, powder-blue skies offered a welcome change from the drab midwestern landscape as winter neared. And later, chugging up serpentine State Route 89A past the old mining town of Jerome, the laboring of the taxi—and, by extension, myself—felt heavy. “Above Jerome, a town destined for some cataclysmic event, the elevation is 6000 feet,” I scrawled in the log. “The car is being pursued by a Coors truck, and it is gaining. It’s a slow-motion, dreamlike race. Trying to run, but I can’t. Creeping, crawling, ever so slowly, with a beer truck closing in, the monster behind.” The alone time had germinated an inkling that I was running from something. But really, a Coors truck? That’s pretty poor paranoia.

After summiting at 7023 feet, the taxi began coasting toward Prescott, but even this glide path wasn’t exactly easy. “The left-front brake is surely worn out,” I added. “As I put on the brakes, sintered brake-pad dust flows freely through the Checker interior. I can hear the pad base wearing and tearing into the rotor on hard stops.” More resigned than concerned, I turned the cab onto a wide shoulder to look for smoke, flames—whatever this next drama held. Nothing. Just the utter quiet of the rocky terrain, a light breeze, and a wispy flight of cirrus clouds assembling to the north.

Per the odometer (highly optimistic, possibly to overcharge passengers?), the Checker had covered over 4000 miles since New York. It was tired and, at least emotionally, so was I. Luckily the Sanyo cassette deck installed before the trip still worked. I hit play and absorbed Glenn Frey and Don Henley’s masterpiece: “Desperado, why don’t you come to your senses?/Come down from your fences, open the gate.” Alone, cold and vulnerable in the mountain air, the verses woke me up, and I reached in the window and spiked the volume to the 6×9 coaxials buried behind the Life-Guard partition. Within seconds, the end, “You better let somebody love you/Before it’s too late,” had me sobbing. At that moment, I decided to gather up my s***, and commit.

Epilogue

The erstwhile Checker Taxicab soldiered on to Route 66’s terminus in Santa Monica on December 18, 1981. The next morning, I jumped in it to run errands, but the transmission rebelled and the car would barely move. I sold it soon afterward, sharing the repair cost with buyer Eleanore, an artsy LA lady who loved the Big Apple. We remained friends, and three years later, the cab became the getaway car at my wedding; a much cheerier Hunter was the chauffeur. Eleanore enjoyed it for a decade before selling it for $400 to Villa Roma Sausage Company president Ed Lopes, who wanted a fun prize for his company’s annual golf tournament.

Lopes concealed it with a blue cover at the event. “Under the tarp, the cab looked like a Mercedes-Benz!” he said. (For added drama, Lopes hired Shannon Rae, a model and later star of the tribute band Rondstadt Revival, to reveal the taxi to the winner. No lie, the band’s song list includes “Desperado.”) The winning golfer was stunned to find that the cab started and could be driven home. He did so and later gifted it to his son’s high school auto shop class, where, after fixing it up, the school used it to carry the principal and dignitaries to football games.

That’s the last I heard of the Checker, and now three decades later, the trail is truly cold. But if you should ever find it rotting in some SoCal carport, approach with caution: I left my old demons inside.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

What a well-written, clever, erudite and enjoyable tale of youthful, risky, highway travel adventure. The Road Trip. John Stein, you have a beautiful mind.

This was my dream in 1980.

I did not have the courage to follow it.

Instead just kept working the good paying job i hated.

Maybe in the next life. . . . . . .

The cab’s styling seems to be a mix of 50’s Chevy to me. Great story!

What a great story.

Excellent writing, and pictures too. Even early in your career you show a good sense of story and composition in your logbook and photographs. Not many people have a high quality narrated slide show of their early-adult adventures such as this.

Cooler than the other side of the pillow. Great adventure and pictures.

The artsy lady, Eleanore, who became the next owner of the cab after the author’s road trip, was my mother. Ever the non-conformist, she delighted in driving it amongst the upper crust luxury cars that populated our West LA neighborhood. It also became the car my younger sister first learned to drive in. Sometimes people would try to hail it for a ride, and after it got passed down to my younger brother, he would often pull over and negotiate a fare with the surprised “customer” to earn some extra money. Definitely the most memorable family car we ever had.

I’ve had a couple of friends who owned Checkers as private transport. They loved them, but strangers just getting in was a constant hazard. People saw them, no matter what color, and just wanted to pay to ride.

Great story! Someday I’ll have to write about my solo trip to (and back, wihout incident!) Mexico City –in a 28hp Renault 4CV…

Ed Cole, formerly of Chevrolet and GM, headed up Checker for a number of years

Shows how a journalist operates, packing a camera with a self timer and keeping a log. My craziest cross country adventure is relegated to my feeble memory.

Nice story and tribute to the automotive bygone for city folk.

As a kid I remember these Checker taxis, can’t recall them ever not rattling, or smelling “weird”. They used to have two little fold down jumper seats that mounted against a driver’s compartment divider – this was an era before they were bulletproofed.

It was a rare sight to see any Checkers left on the road as taxi’s transitioned to Ford, Chevy and Plymouths.

But noteworthy, back in the late ‘70’s, one sparkling Checker rolled up next to me at a traffic stop downtown Chicago, a head turner because very few if any civilianized Checkers were about, even de-badged taxis.

I was surprised to see Illinois Governor Thompson in the back, took time to wave hello from the back of his official State vehicle – an all black late model Checker Marathon I think with chromed bumpers too…and governmental license plate # 1.

What a great story. Occasionally, you can find one that is still running in sites like Hagerty, Auto Trader, etc., but there are only a few across the lower 48.

Loved this story

You had me at Checker and wow, that story just sucked me right into that road trip. Get working on that screenplay! Thanks for crafting a beautiful painting of a story and taking all of on that adventure.

Great story!! I love a good road trip. Since nobody asked….what became of Paula?