How to design an award-winning SEMA build

Every year, the Specialty Equipment Market Association, widely known as SEMA, takes over the Las Vegas Convention Center with its showcase of all things automotive aftermarket. The 3.2 million square feet of event space is packed to the brim with multitudes of vendors displaying their wares. Outrageous, fender-flared customs are the canvas.

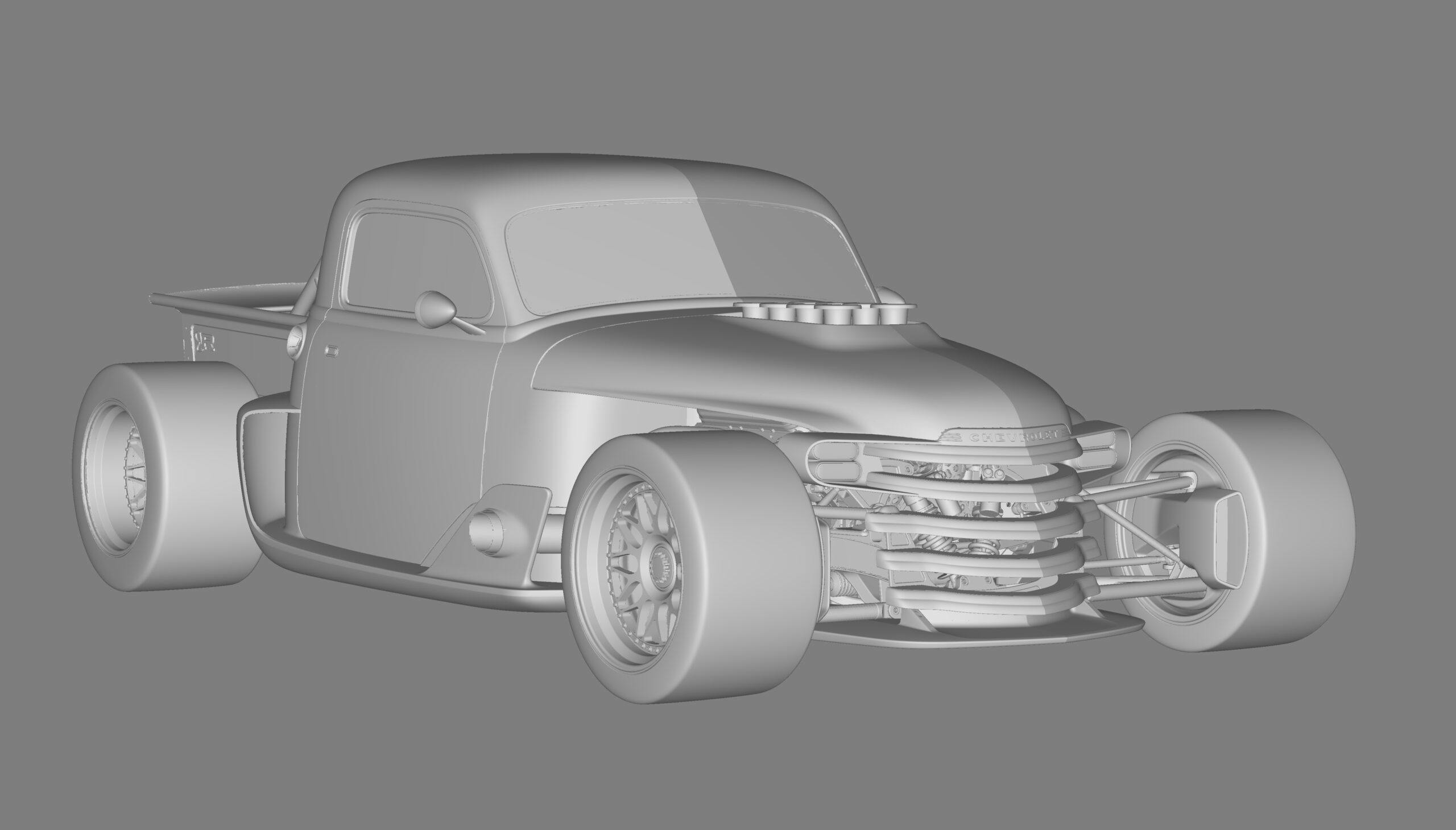

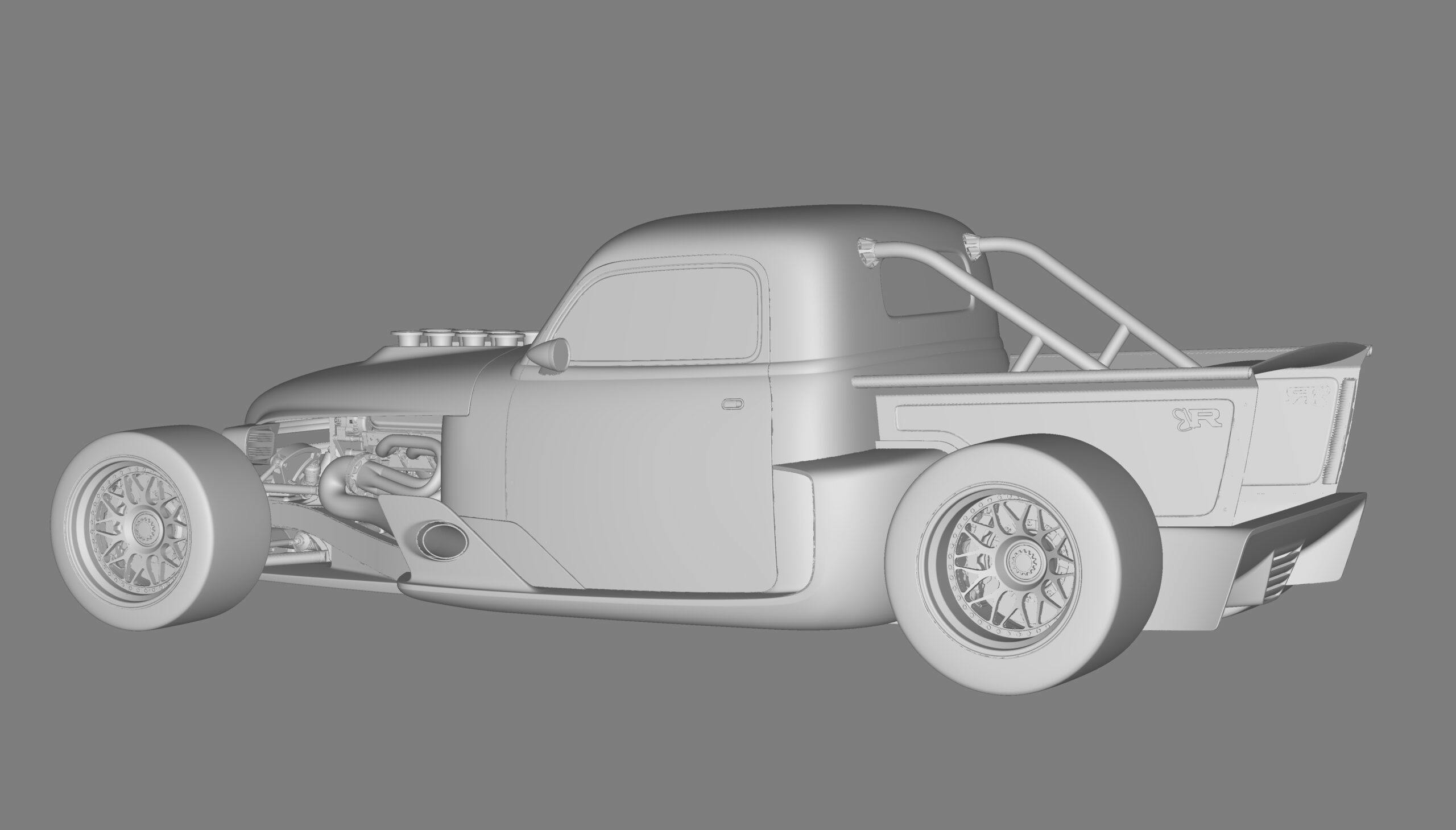

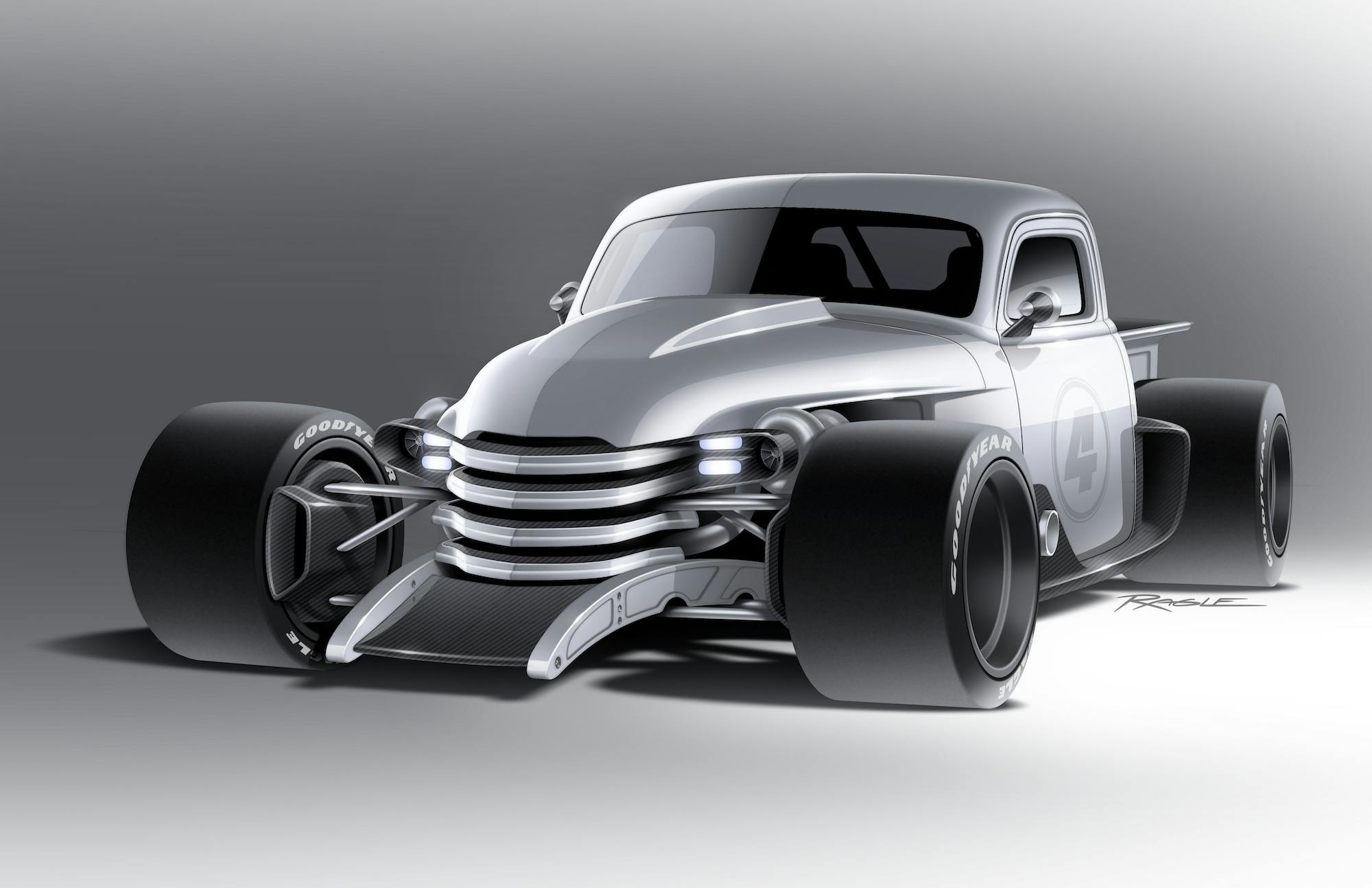

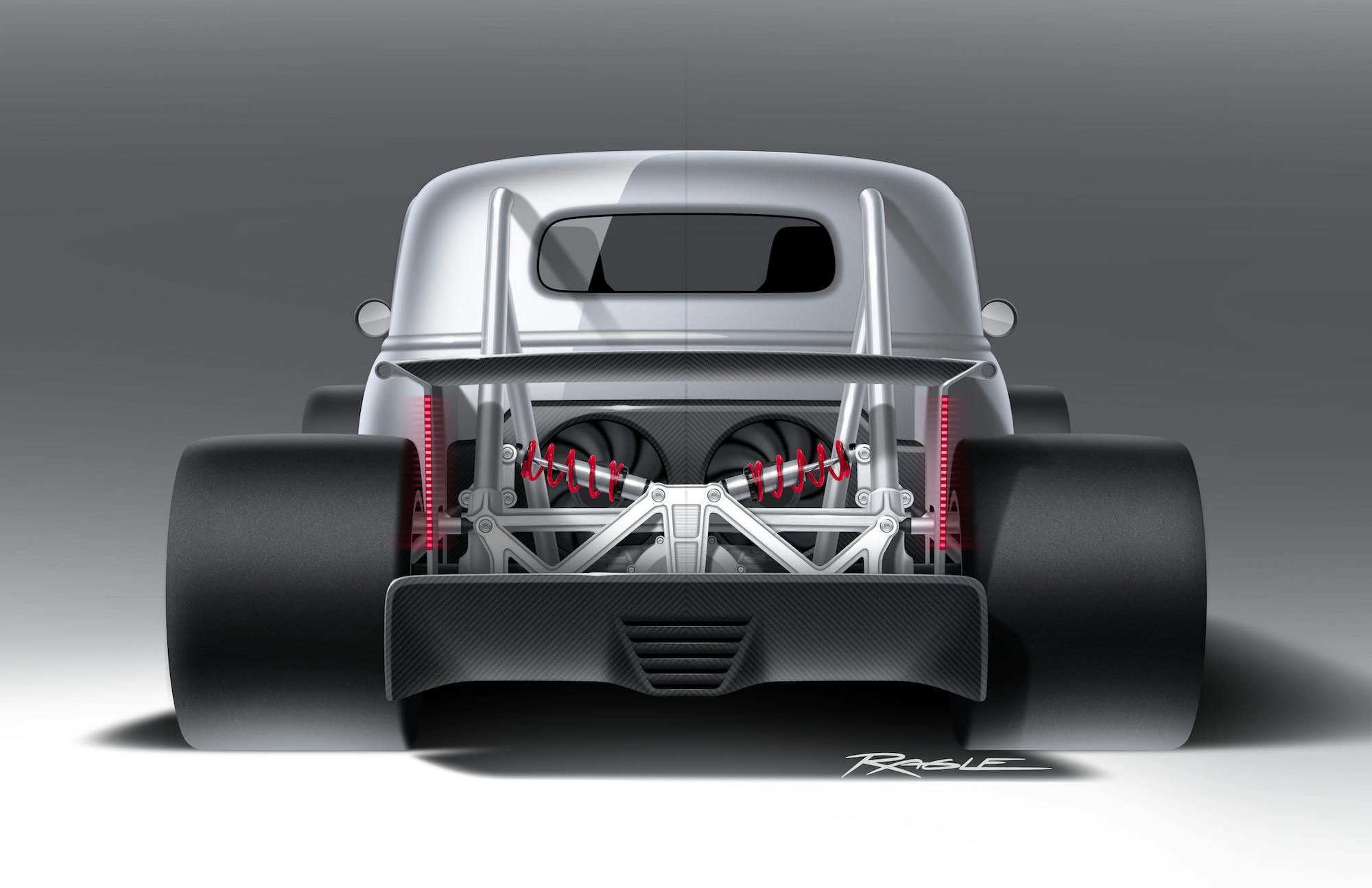

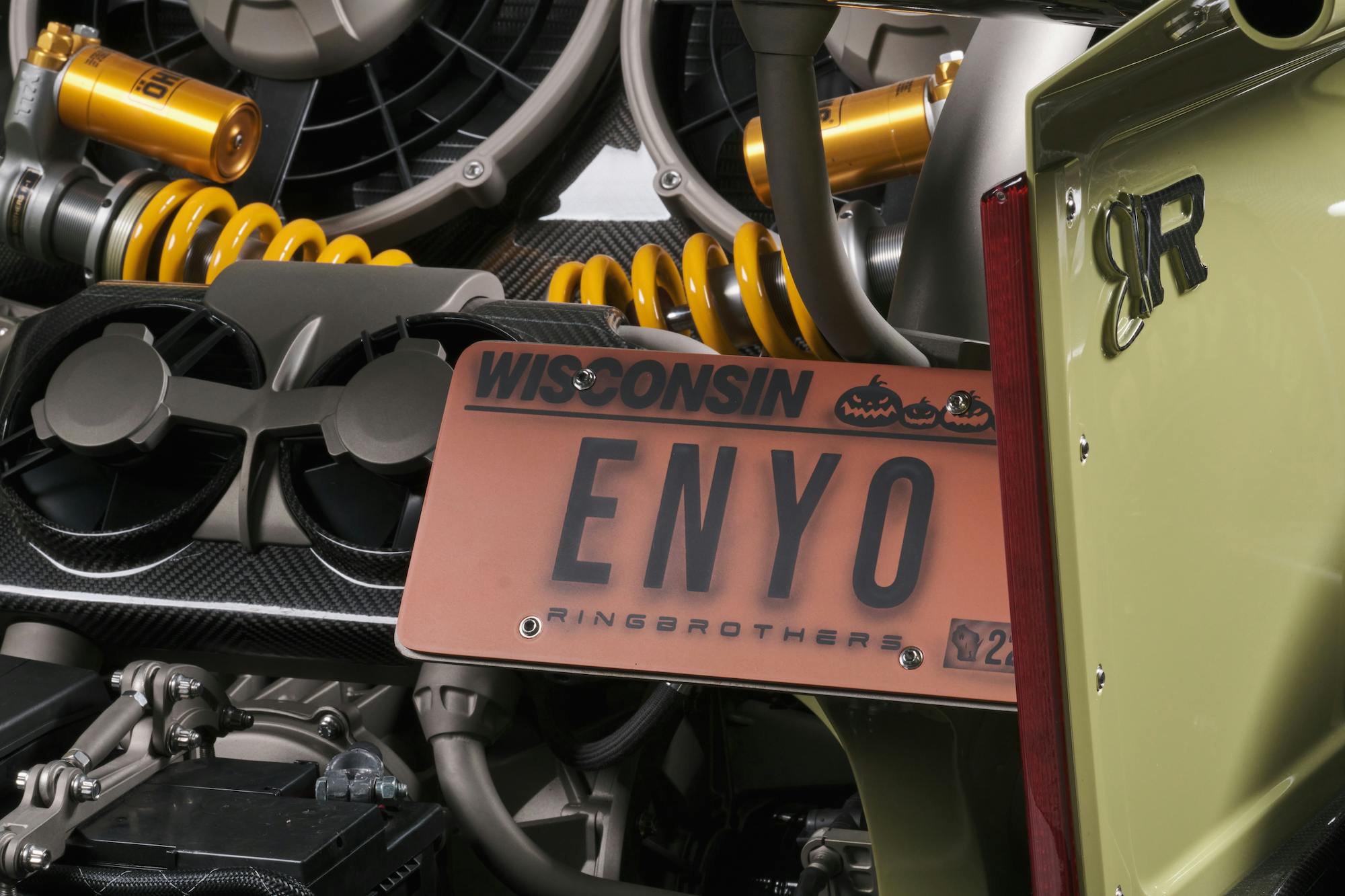

One builder that stands out from the crowd of cars at SEMA is the Ringbrothers. Riding the pro-touring (highly customized muscle cars with race-car level handling capabilities) wave that started in the early 2010s, the Ringbrothers have gained a reputation for delivering high-dollar, modern takes on American iron. This year, the company displayed four cars at SEMA: “Bully,” a 1972 Chevy K5 Blazer; “Patriarc” a 1969 Mustang Mach I; “Strode,” a’69 Camaro; and “Enyo,” an open-wheeled, F1-inspired 1948 Chevy pickup. The “Enyo” took top honors at the Battle of the Builders—a SEMA Show competition in search of the best modified vehicle.

After looking at a fenderless, center-lock-wheel-equipped farm truck, a reasonable question would be, “Who even comes up with this stuff?”

Meet Gary Ragle. He designed all four of the Ringbrothers’ rides showcased at the 2022 SEMA show.

Ragle is a seasoned industry veteran, with over 20 years of professional automotive design experience. After graduating from the University of Cincinnati’s transportation design program, he spent seven years working at Mitsubishi’s California design studio. He left Mitsubishi around 2009 and started to take freelance design work from local hot-rod shops while looking for new employment. He eventually found short-term gig at Ford’s Dearborn studio, but he became frustrated with the bureaucracy and sheer attrition of the corporate design process. After his contract was up, he decided to move back to Cincinnati and become a full-time freelance hot-rod designer.

I had the pleasure of catching up with Ragle after SEMA, and we delved into—among other things—his process for dreaming up high-end hot-rods, customs, and muscle cars.

***

Chris Stark: What’s does the design process for a typical custom build look like?

Gary Ragle: Typically, the Ringbrothers will have a customer that knows what type of car they want to do, like let’s say a ‘65 Mustang fastback. More often than not, that’s their only requirement. But I’ve built such a good relationship with the Ringbrothers that they don’t feel like they need to hold my hand on every design choice.

After the car is picked out, I start doing typical design process—rough sketches; find something that works a little bit better [and] run it by Ringbrothers; more finished renderings and show those to the customer. From there, I might tweak the design a little depending on their feedback. If Ringbrothers are fabricating a complicated shape, like a hood or a fender or a body shape, we’ve been doing CAD modeling for them. They’ll 3D scan the vehicle and I’ll use that scan to create the part in Alias [a professional CAD program].

All the carbon-fiber body and everything are done from those molds from my data out of Alias. But yeah, that’s how we’ll tackle the muscle car. There may be fenders, hood, lower balance or something like that. Done an Alias along with a number of sketches and renderings, and Ringbrothers will take it from there.

CS: With your muscle-car reimaginings, are you changing the proportions? Are you widening things? What goes into that creative thinking process?

GR: Yeah, it depends on the car, of course. I always tell my customers, “Let’s make changes for improvements. Let’s not make change for the sake of change.” A ‘69 Mustang Fastback is a pretty badass car the way it is. We all like it for a reason, so there’s no need to change what works. It’s about pinpointing those areas like where can it be improved. On some cars, that’s a real challenge because they’re so nice. On other cars, it’s a lot easier because they’re ugly or have some strange proportions. That can be addressed.

For example, there was a blue ‘69 Mustang Fastback, the Ringbrothers just showed at SEMA. The rear quarters were widened, but the front was left alone. If you look at the design of the vehicle originally, that’s almost what it wanted. It had the big, strong rear haunches and shoulders over the rear wheels. It’s almost like you could see [how] the original designers wanted that to be emphasized, whereas the front is a little bit more straightforward and linear and it wasn’t necessary to change. That car was a good example of just finding those areas that needed to be amped up a little bit and leaving everything else alone.

But with the Enyo in particular, that was really design intensive. It was easily two to three times the work of any normal build, like a Mustang.

CS: What went into the Enyo and what made it more challenging than a typical Ringbrothers build?

GR: You’re taking something that was never really meant to be open-wheel and making it open-wheel.

I wanted to have a lot of sidewall on the tires to make it look like an old ’80s Formula 1 car. We had to pick the tires first because that was the only part you can order from a catalog. Everything else was custom. I talked to Mike and Jim Ring [owners of Ringbrothers] and I was like, “Well, we’re trying to do a race car, so I think slicks would be pretty cool.”

They agreed, so I started looking online for the biggest set of tires that I could find for an 18-inch wheel, which happened to be Goodyears. And then the second biggest size available, we just put on the front.

Once we had the tire size established, I mocked everything up in CAD. They had a scan of the original ‘48 Chevy truck cab, and we brought that in, placed it in between the wheels. I had a rough side view sketch at that time and then just started slicing and dicing and moving the cab around.

The width of the vehicle was basically established by the opening in their trailer because wider is better, right? I said, “Okay, well, what’s the maximum width we can do,” and they’re like, “Well, we got to fit it in this trailer.” I was like, “Okay, give me the width of the trailer and I’ll subtract an inch and give you a half-inch clearance on either side.”

CS: That’s hilarious.

GR: Right. Isn’t that awesome? The cab was completely scaled down to look right with that tire size. The top was chopped four inches. It was narrowed down the middle four inches, and six inches of the bottom of the cab were cut off. We had some discussions once it was mocked up about the height of the owner and he was little on the tall side. Even though we lengthened the cab two inches to give him a little bit more leg room, it looks proportional. I don’t think people realized just how much it’s been cut up.

CS: I had no idea. That’s cool that you can make all those changes and still have it look like the original truck. I figured there was some custom work, but I didn’t know it was so extensive.

GR: Yeah, the cab is the only original steel body panel left on it. Everything else, body wise, is carbon fiber. The doors are carbon-fiber, the hood, the grille, the bed. The bedsides were made to look like the old flat metal bedsides, but they’re all carbon-fiber.

CS: Was it a struggle to balance the needs the engineering and the chassis setup with what you were going for aesthetically?

GR: Not so much in this case. It is in any type of OEM setting, or when you’re working for a car company, that’s always the challenge, of course, designers and engineers. But because I was trying to make it look like a race car and the engineering side of things was no-compromise race car. There was a race-car engineer with a background in IndyCar and Le Mans who laid out the chassis and suspension. I worked with him on all the aerodynamic stuff to make sure it was realistic. We’ve never had it tested per se, but it is all real, functional stuff. The only thing I wanted but didn’t end up on the final car was a super deep offset on the wheels. That’s not always ideal from a performance standpoint but nixing the wheel specs wasn’t that big of a deal.

CS: Yeah. That’s a big plus side for doing hot rods rather than working with OEMs is not having to worry about crash safety or CAFE standards.

GR: Everything is basically like a concept car. If they can cut it and weld it and the money and the time is there, everything is possible.

CS: I mean, that sounds ideal.

GR: Yeah, it is my favorite thing about doing the hot rods. I miss the blank sheet of paper approach that you to futuristic concepts or advanced production in a studio, but it got very old making warehouse filler. Ninety-nine out of a hundred things that you do at a car company are never going to see the light of day. You pour your heart and soul into it and it gets killed for whatever reason. And then it’s just, “Okay, that model’s going to the warehouse and here’s the next one.”

CS: Were there any other difficulties with the Enyo?

GR: The other thing that made it so involved and such a long process was that it [the build] is almost like a motorcycle. You can’t hide anything. Everything had to be finished and made to a high standard because there was no fenders or hood sides or anything to hide all of the mechanical elements.

CS: What’s your design philosophy?

GR: More aggressive is better. Every time I sit down and sketch something, I just want it to be as badass as possible, personally, and typically, that’s the goal for any type of hot rod too. It’s just supposed to be a loud, hot, tire smoking, badass machine. That probably informs more of my design style or philosophy than anything else when it comes to these cars, just maximum badassery.

CS: With the Ringbrothers in particular, or maybe just any customer build, are you aiming for it to win at SEMA or are you just trying to give the customer the best car you possibly can?

GR: Yeah, usually we just give the customer the best car we can. Sometimes the customer’s goal is to win some award. The Ridler Award at Detroit Autorama is a big one that you have to build and design a car specifically for that award. I’ve been involved in a couple of those cars, and you have to design them with that award in mind if it’s a goal—just because [the judges] are so specific about what they’re looking for. But most of the time, I don’t design for any specific award. The customer is the one paying the bills, so they need to be happy.

CS: You’re known for your muscle car work. Is that typically what you’re into or is that just where the market is?

GR: I’ve made a name for myself when it comes to more design with these modernized muscle cars or pro-touring cars or whatever you want to call it. That’s really hot right now, so most of my clients come to me for that type of work. It’s not to say that’s all that I would do. I tell people, “I’ll do anything with wheels.” That’s where I draw the line. I don’t want to do product design.

When it comes to my own garage, I like more traditional hot rods. I don’t want my personal cars to be trendy because, in 15 years when I actually get one of these things finished, I want it to still be cool.

CS: If one of your clients gave you a blank check and told you to design something cool, what would you pick?

GR: I’ve got a few things in my mind that I’ve sketched over the years. One is a Shelby Cobra. That’s all I can say about it. I don’t want to give anything away of what I’d want to do to it, but that is one that I would like to play around with. And then honestly, if I ever had actual money to do it, my capstone project from back in college. I always thought there was something there and I think that would be a fun car to dive into again, having 20 years experience beyond the point when I did that.

CS: What was your capstone car? I don’t remember seeing that.

GR: It was hot rod inspired, this tandem seat roadster. It had fenders, but more of an open wheel type vibe to it.

CS: Speaking of college projects, do you have any advice for young people trying to get into car design?

GR: I’m pretty old-school, so I would say, “Just do everything you can and just sketch cars, take figure drawing classes, just learn to draw.” You spend almost all of college learning to draw cars properly because it’s so hard to draw a car.. There’s almost no time to learn to design cars. At least with me, I spent those five years learning to draw properly just so I could get the ideas in my head out onto paper. I didn’t learned to design until I was at a car company.

It’s not a big philosophical bit of advice, but your life is going to be easier in college the sooner you can draw better.

CS: Is there anything you have in the works that you can talk about? What’s the next big thing?

GR: That I can talk about?

CS: Yeah.

GR: I’m working on a couple projects for Ringbrothers right now that should be pretty cool. It’s going to be hard to top what we just did.

I also have a customer overseas [for whom] I’m working on a Porsche project. That’s about all I can say about it.

CS: That’s exciting.

GR: Yeah, it’s cool. I’ve never been personally into European cars or vintage Porsches or other vintage European cars. It’s something different than a ‘69 Camaro or a Mustang or one of those typical cars. It’s been fun for me to dig into that.

***

That truck is by far the ugliest thing on four wheels. Way too much of everything. Out of all the vehicles I have seen built by the “Brothers” only their F100 shop truck was worth looking at, the philosophy of “If some is good, more must be better” is not always tasteful in car building. Your opinion may vary.