The last Packard that never was: Dick Teague’s Predictor

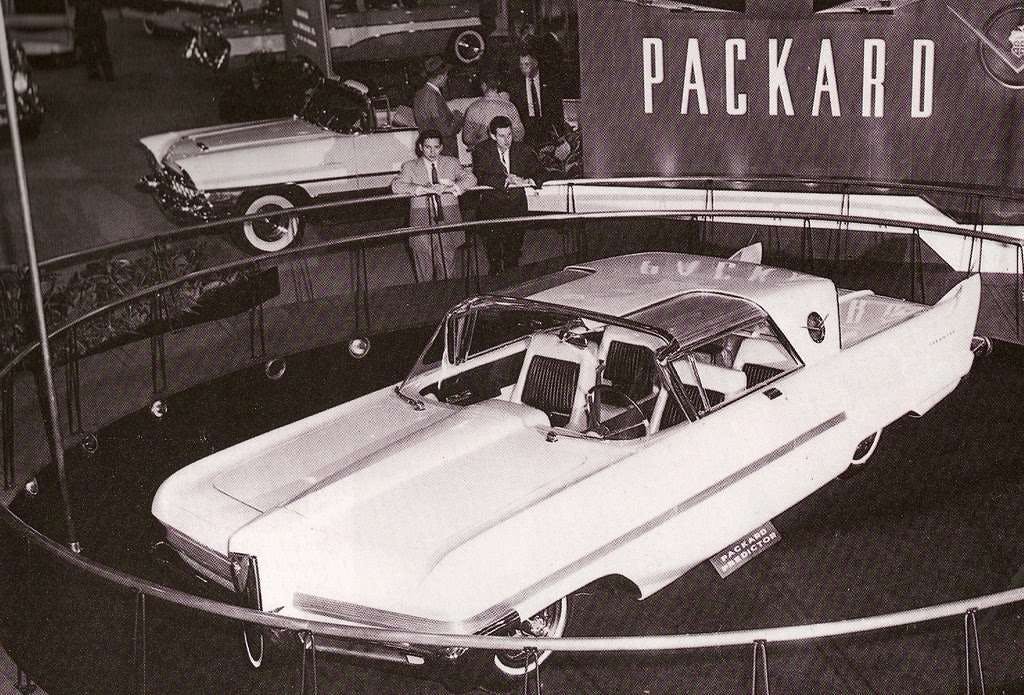

One of the events canceled this summer due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been the EyesOn Design Car Show, organized by Detroit’s automotive styling community to benefit the Detroit Institute of Ophthalmology and held at the Eleanor and Edsel Ford Estate. In many ways it’s a special car show, not the least of which is the fact that you get to see many of the cars actually being driven as they go up and down the quarter-mile-long driveway to the reviewing stand in front of the estate’s Tudor mansion. I was looking forward to this year’s show in part because I’d get to see the Packard Predictor, the 2020 show’s poster car, in motion.

For much of the early 20th century, Packard was arguably America’s most prestigious luxury automobile brand. Along with Peerless and Pierce-Arrow it made up the “Three Ps of Motordom” that sat at the pinnacle of American automotive luxury. Of course, just because you make luxury items doesn’t mean you’re immune from financial failure. Peerless and Pierce-Arrow didn’t survive the Great Depression. Packard made it out of the 1930s by introducing a line of less expensive cars, and while some Packard purists insist that tainted the brand, dooming it, the fact is the “junior” Packards and Clipper that followed likely made it possible for the brand to make it into the ’50s. By 1954, though, Packard was in terrible financial shape. Earlier, Nash’s George Mason and Packard’s James Nance had proposed a merger with Nash, Hudson, and Studebaker to create a company that would have been bigger than Chrysler and actually might have succeeded. Unfortunately, egos and Mason’s sudden death put an end to those plans. Packard did end up merging with Studebaker to gain access to a larger dealer network and achieve some economies of scale, but the South Bend-based car company turned out to be in worse financial shape than Packard. While the Studebaker Corporation, which was diversified, was profitable, its car-making division was selling about 80,000 units a year, when it needed to sell almost four times that number to turn a profit.

In 1956, Nance resigned and Curtiss-Wright—seen as something of a saving angel—acquired control of Studebaker-Packard. As it happens, Studebaker was a highly diversified and profitable company as a whole, but its car-making division was a financial black hole. Curtiss-Wright shifted Packard’s government contracts to its own defense companies, closed the remaining Packard factory, and for a couple of years tried to sell piscine-looking monstrosities as Packards, although they were really Studebakers with very badly executed face lifts. The last true Packards were 1956 models. Ten years later, Studebaker was dead as well.

Fast forward six decades. Going up to the third floor of the Studebaker museum in South Bend is like entering an alternate automotive universe. There is a display of some mid-’60s Studebaker styling proposals that never came to fruition, like a four-door Avanti by Raymond Loewy and some very sharp-looking sedans by Brooks Stevens that might have brought customers into Studebaker showrooms. Those make a visit to the museum worth the trip (though it’s pretty neat to see Abraham Lincoln’s carriage as well; Studebaker was a very old company), but only a few feet away is possibly the facility’s greatest attraction, and it’s not even a Studebaker.

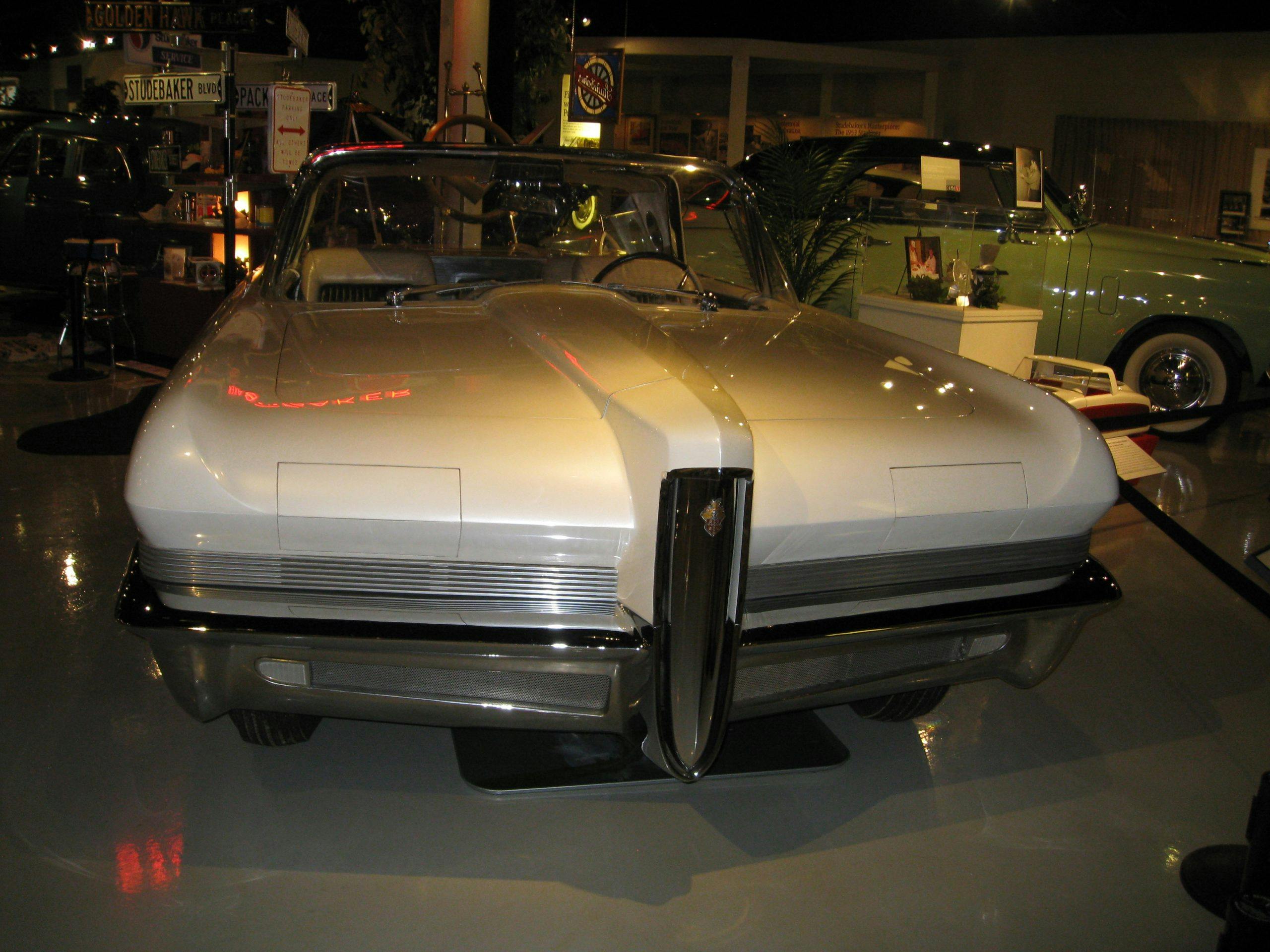

That would be the Packard Predictor. I don’t know if the Predictor would have saved Packard, but in many ways it succeeded in predicting the path that automotive styling took in the late 1950s and into the ’60s.

The Predictor was first introduced at the Chicago Auto Show in early 1956, and in a year that many now-legendary concept cars were introduced, the idea car was an unqualified hit. I’m personally a fan of the last real Packards, particularly the ’56 Patrician. Dick Teague, head of styling at Packard, who would later helm design at American Motors and create the AMX and Javelin muscle cars, had done a masterful job of turning the stodgy body of the early ’50s Packard into something that doesn’t look out of place next to a ’56 Chevy. As classy as I think the last Patricians were, the Predictor looked nothing like the production Packards, in which gentlemen could wear fedoras behind the wheel with plenty of remaining head room. The Predictor was long and low and sleek and stylish.

The idea for the Predictor was from William Schmidt, who came over from Ford in 1955 to become head of styling for Studebaker-Packard. Schmidt was no stranger to forward looking concept cars, with the Lincoln Futura on his resume. The Futura is better known as the basis for the Batmobile used in the mid-’60s television series. In an article in the February 1956 issue of Car Life magazine, Schmidt said, “The Packard Projector is a portrait of styling philosophy. While futuristic in the sense that it features many advanced styling and engineering innovations, the Packard Projector is not a ‘dream’ car. Many of its features are on present Packard models, and those not of the present are in every case practical and under serious study for production models.” Projector? Back in 1956, monthly magazines had lead times of up to three months between a story being written and the date of publication. Just before the concept’s introduction, the name was changed to Predictor. I haven’t yet been able to find out the reason for the name change, but coincidentally Dick Teague wanted to call it the Javelin, a name he would go on to use at AMC.

The, ahem, concept of building forward-looking one-off prototypes that could be displayed to the public in order to sell more mundane production vehicles goes back a long way. GM styling chief Harley Earl’s Buick-based Y-Job, introduced in 1937, is generally credited as being the first concept car produced by a major automaker, although it followed 1929’s Auburn Cabin Speedster. Virgil Exner liked to called them “idea cars,” and Chrysler’s first two, the Chrysler Newport and Thunderbolt debuted in 1941. During World War II, automotive designers were more likely to be drawing concepts for tanks or missiles than for passenger cars, but General Motors was back in a big way with its Motorama exhibition, which was introduced in 1949 and ran to ’61. The Predictor was hardly Packard’s first concept vehicle. The production Caribbean was based on the 1952 Pan American, styled by Richard Arbib, and Dick Teague’s 1953 Balboa had a reverse slant rear window that may have been borrowed by Lincoln and Mercury stylists later in that decade.

By the mid-1950s, Packard sales had slumped seriously and, combined with Studebaker’s financial shape, rumors were circulating of Packard’s impending demise. To demonstrate that Packard was still a viable, forward-thinking company, Schmidt and Nance wanted a show car that could excite dealers, potential buyers, and, most importantly, bankers who might extend the company some badly needed credit. A two-door hardtop was considered to have the widest appeal, so that was the design brief Teague was given. At the time, Packard was considering making a deal with Ford to use a Lincoln platform as the basis of its next line of cars, so the concept had to be long. The completed Predictor was 222 inches in length. That’s six inches longer than a ’57 Cadillac coupe. Ironically, Teague used a Clipper chassis as the basis for the Predictor, as he thought the larger Patrican frame would have made the car too long. He told Special Interest Autos in 1978 that the Predictor was “long enough to package the things we wanted to get in the vehicle.”

As far as using a concept to introduce production features, the Predictor had features which Packard had recently introduced, such as the company’s own modern V-8, in the Clipper’s 352-cubic-inch, 260-hp version, and Packard’s exclusive self-leveling Torsion-Level suspension, along with lots of push buttons. Push-button operation was big in the ’50s. In terms of aesthetics, Teague eschewed the literal pounds of chrome that typically adorned luxury automobiles in the 1950s, though the Predictor still has fairly massive chrome-plated bumpers and a wide brush-finished aluminum or stainless-steel belt circles the front two-thirds of the car. “This car proves that chrome is not a must for making an automobile look attractive, that beauty can be sculptured in steel,” Schmidt hyped. “The Projector accomplishes this in fine proportioning, flowing lines,and beautiful radiuses, and integration of surfaces in pleasant shapes.”

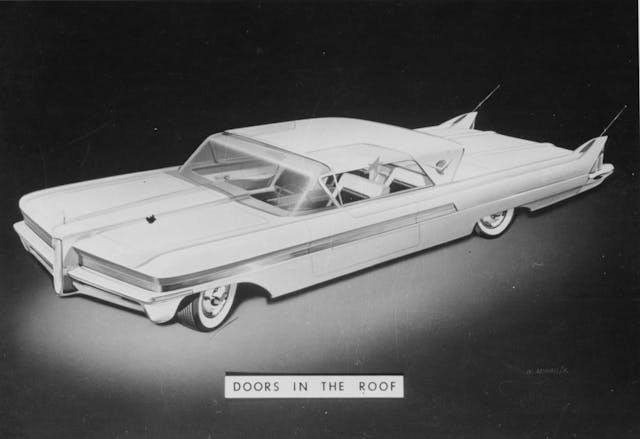

It’s hard to choose which feature stands out the most. While some people think the Predictor’s “nose” looks a bit like the Edsel’s infamous grille, Teague was giving a nod to Packard’s traditional “horse collar” or “ox yoke” radiator grille. That prominent proboscis fronts a power bulge in the hood that flows through the bottom of the windshield, creating a binnacle for instruments, a clever and unique design. Above the side windows were one-of-a-kind retractable roll-top steel panels that give the Predictor an al fresco feel and predated T-tops. The oversized Plexiglas windshield had an extreme dog-leg that extended into the passenger compartment. Packard hyped the “picture window” glass, but in fact visibility was restricted by the roll-top roof panels which extended below the roof line. On the other hand, a gentleman could probably wear a fedora in the Predictor with those panels retracted. The C-pillars were cantilevered both fore and aft, reprising Teagues’ Balboa backlight, which, as implemented in the Predictor, could be lowered at the push of a button. The rear end featured the ultimate version of Teague’s “cathedral window” tail lamps (first seen on 1955 production Packards), smartly integrated in flow-through tail fins.

The backlight wasn’t the only feature operated by push buttons. Postwar consumers had their choices of labor-saving devices at home, and with the market success of automatic transmissions and power steering, automakers were big on making everything on their cars easy to use. Schmidt said the Predictor reflected Packard’s “basic development goals, which call for elimination of the human element in motor car operation.” That may fall harshly on enthusiast ears, but Packard was just responding to the market of the day. In addition to the rear window, the side glass, roof panels, hidden headlights, Ultramatic transmission, and other features were operated by buttons, although the swiveling front bucket seats to ease entry and egress were manually rotated. Apparently, to get the seats to swivel meant dispensing with adjustable seat tracks so the Predictor is a bit uncomfortable to drive if you’re very tall or very short.

Fabrication was jobbed out to Turin’s Carrozzeria Ghia, which also was responsible for building many of Chrysler’s concept cars in the 1950s. Chrysler picked Ghia because it was impressed with the quality of the Italian coachbuilder’s work and prices lower than what UAW labor would have cost in Detroit. While Packard was struggling financially, it was committed to the Predictor project, eventually spending $70,000 on it (about 10 times that much in 2020 dollars), so money wasn’t an issue. Perhaps Ghia’s promise to complete the job in three months was a deciding factor. Packard executives wanted the car ready for the 1956 auto show circuit. It’s also possible that Schmidt was just comfortable working with Ghia, which had fabricated the Futura while he was at Ford.

Ghia delivered the Predictor by the promised deadline; it just wasn’t completed. “The electrical system … was an absolute mess. We had all kinds of shorts and fires and smoking wires and noises,” Teague said, and the interior still needed to be fitted. Teague’s team came up with a sharp-looking black-and-white interior trimmed with reversible upholstery, cloth on one side and leather on the reverse. The center console has controls that wouldn’t look out of place in a jet cockpit and possibly influenced a similar console design in the Studebaker Avanti. Additional controls were located in an overhead console as well. Detroit’s Creative Industries, fabricators of many of the Motor City’s concept vehicles, was brought in to fix the wiring issues.

By show-car criteria, the Predictor was a huge hit. It made the covers of Car Life and Motor Life magazines, went on a nationwide tour of Packard dealers, where it drew pretty good crowds, and Packard brass used it to schmooze bankers and other possible financial backers. Unfortunately, Ford killed any chance of licensing Lincoln platforms to Packard, and on June 15, 1956 Packard production ended. Two months later, Curtiss-Wright started the process of selling off Packard assets.

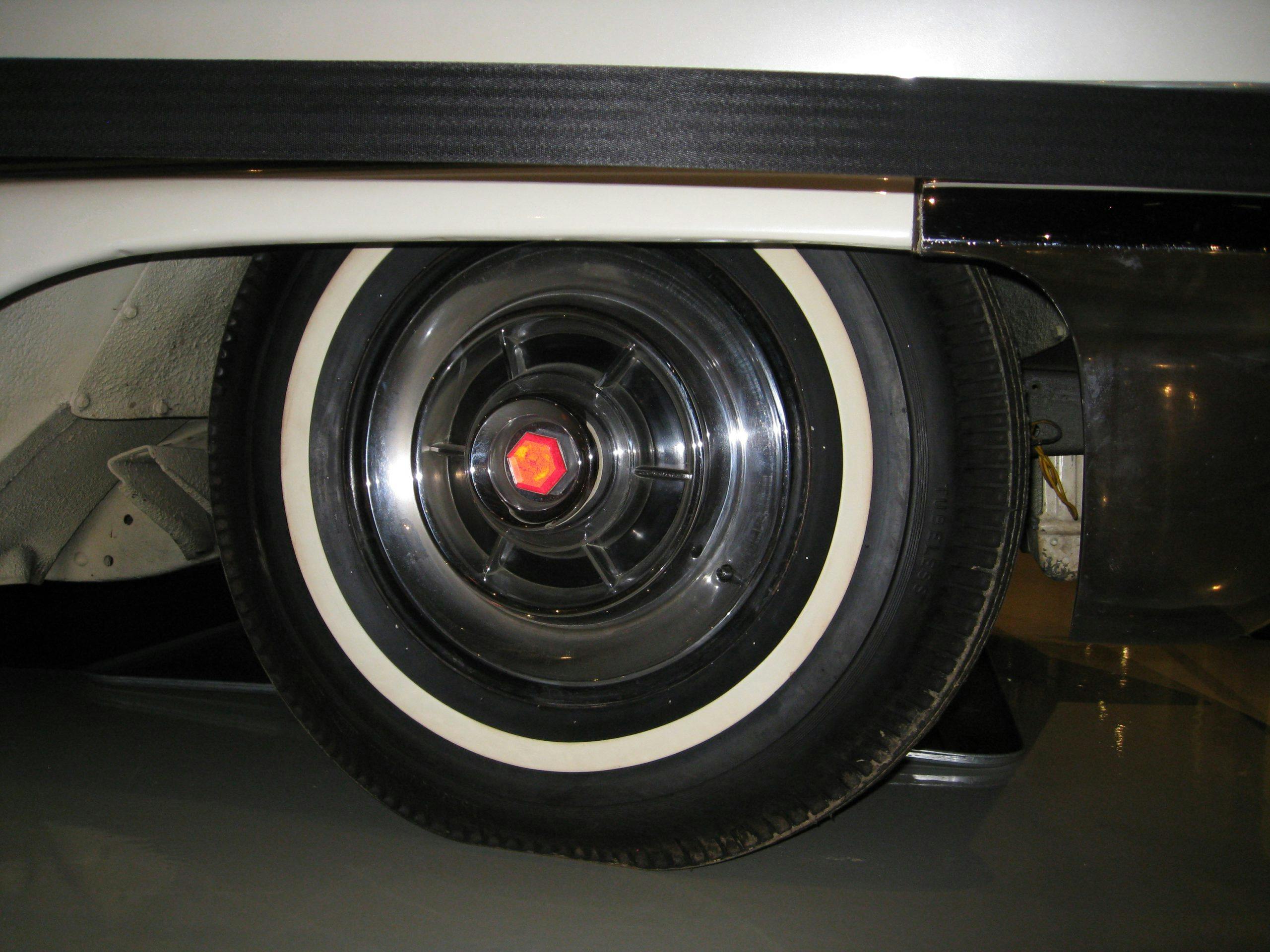

The Predictor could have ended up as scrap metal, but fortunately for automotive history, the concept car was given to the city of South Bend as Studebaker was going out of the car business, eventually passing into the collection of that city’s Studebaker National Museum. In the late 1980s, the Museum had the Predictor sensitively restored by Packard specialists LaVine Restorations of Nappanee, Indiana. Eric LaVine told Hemmings that Ghia’s metal shapers did a good job, though he agreed with Teague’s characterization of the Predictor’s wiring. Stripped down, the Predictor proved to be all steel, with no body filler, and tight panel gaps. Even with 260 horsepower, the Predictor’s performance will not take home any trophies from the drag strip, as LaVine figures that the car weighs about three tons. The doors are about 10 inches thick, with steel inner panels.

Once stripped, the Predictor was resprayed with a period-correct pearl white finish, though modern paints with a white base coat, pearl midcoat, and eight layers of lacquer clear coat were used. The relatively minimalist chrome was replated and the interior carefully cleaned. Little was needed in terms of restoring mechanical components. LaVine refilled the fluids and fuel, and the Predictor started right up and ran, or rather jogged, considering its mass. Apart from the paint, the Predictor is almost completely original. Almost, as the torsion bars in Packard’s trick suspension were sagging from all that weight, so a set of adjustable inflatable air-shocks were added. The original windshield was retained, despite severe crazing, as the museum’s budget for the restoration didn’t include $30,000 for a custom-made windshield.

Since then, the Packard Predictor has been on display at the Museum, which is highly recommended if you’re in northern Indiana or southwest Michigan. Add in the Gilmore Museum, near Kalamazoo, and the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Museum, in Auburn, and you can make a car museum vacation out of it.

The Packard Predictor may have predicted the long, low lines of many ’60s cars, but it never really had a chance to change Packard’s fortune. Packard’s eventual demise was pretty much baked into the Studebaker-Packard cake. Thousands of car companies have failed over the past 120 years. Most went down without much of a trace, but the Packard Predictor gives us a tantalizing clue about what might have happened had America’s preeminent luxury car brand survived.

If only!