RX-7th Heaven: Venturing far beyond Mazda’s affordable sports car intentions

Toasting Mazda’s 100th birthday is just cause for rolling my trusty RX-7 out for a zing or three past its 7-grand redline. While you savor these shots of my favorite family heirloom, I’ll reveal how I became a staunch rotor head (Wankel engine aficionado). In 1972, shortly after the earth was deemed round, I enjoyed a journalistic boondoggle to Unterturkheim, Germany, to visit Mercedes-Benz’s main manufacturing plant. Hemmed in by Stuttgart sprawl, the wily Germans doubled the length of the test track adjoining their facility by erecting a near-vertical 180-degree turnaround loop. That atypical feature was promptly nicknamed “The wall of death” because it scared the bejesus out of everyone who experienced even one pass around it.

Our hosts were too savvy to allow any journalist to risk their neck actually driving through this treacherous bend. Instead they offered thrill rides in their most spectacular vehicle—the experimental Mercedes C111 gull-winged coupe—with their most illustrious engineer, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, at the wheel. In the 1950s, Uhlenhaut’s hands were the last to touch this brand’s Formula One single seater’s steering wheel before Juan Manuel Fangio strapped in to race.

Originally powered by a three-rotor engine, the C111 had been upgraded to a 350-hp four-rotor Wankel shortly before my visit. Though he would retire later that year, Uhlenhaut radiated utter confidence in the task at hand. After the starter whirred and the C111’s engine wailed like a fire engine, a smile of satisfaction spread across his face. What Uhlenhaut knew was that my three-lap ride in his sports car was about to be forever etched in my memory.

We never ventured anywhere near the C111’s 185-mph top speed. In the vertical turn, the windshield displayed nothing but warped cement. Hanging on was unnecessary because g-force pressed my torso deeply into the bucket seat.

Uhlenhaut’s hands held steady, applying not one smidgen of steering correction. The four-rotor sang like Celine Dion belting out Bizet’s Carmen aria.

Regrettably, Mercedes-Benz lost not only the Wankel scent but interest in selling a proper mid-engine sports car. Permanently and irrevocably addicted to rotaries, thanks to this C111 experience, I pursued such engines with utmost vigor throughout the ’70s and ’80s. A few highlights:

In 1973, while at Car and Driver, Patrick Bedard and I campaigned a Mazda RX-2 in IMSA’s RS road racing series, racking up two wins and one second-place in five events. We were so uncatchable that our rotary ride was banned at the end of the season.

In ’74, I built and drove a Mazda RX-3 powered by a potent Racing Beat two-rotor engine to set a 160.3 mph G-Production record at the Bonneville Salt Flats. Spectators pawed their ears each time I left the starting line with my Celine Dion exhaust shredding the air.

In ’78, I advanced the rotary cause to 183.9 mph in a Mazda RX-7 constructed by Racing Beat, earning an E/GT record on the salt.

In ’79, the RX-7 I co-drove at the 24 Hours of Daytona broke an axle housing weld, DNFing the Racing Beat-built ride during the 17th hour. RX-7s campaigned by Mazda’s factory team fared better, earning first and second places in GTU and fifth- and sixth-overall standings. This time the Celine Dion din rendered me deaf for two days.

In ’80, while campaigning an RX-7 borrowed from the press pool at the Nelson Ledges Longest Day 24-hour race, my team suffered defeat by Road & Track due to high consumption and the fuel pump’s inability to drain the bottom half of the tank. After finishing second, three laps in arrears, our tailpipe glowed red several hours after the race.

In ’86, I logged a two-way blast across the salt flats in an RX-7 Turbo aggressively prepared by Racing Beat, averaging 238.4 mph (best pass 244 mph), earning the C/GT record, still in the books.

While the occasional race or burst of speed placated my rotary withdrawal symptoms, the permanent fix is the ’79 Mazda RX-7 I purchased new after attending the car’s 1978 launch in Hiroshima, Japan. With lots of help from Recaro, Racing Beat, and other tuning vendors, I constructed what was dubbed Tech Director’s Toy when it appeared on C/D’s January 1981 cover.

My goal was moving the 100-hp, first-gen RX-7 in the Porsche 928 direction. In retrospect, that seems slightly ludicrous, but the corners of this car’s performance envelope were stretched and it did become a significantly more entertaining car to own and drive.

To boost power, I yanked the original rotary to install Mazda’s 13B engine containing rotors 0.39 inches (10mm) wider than the stock 12A engine. The new powerplant dropped in nicely because its exterior dimensions match the 12A except for an overall length greater by 0.79 inches. To finish the swap, I bolted on Racing Beat’s Holley four-barrel carburetor intake and tubular exhaust package. The end result was a 50-percent gain in output to 150 hp at an estimated 6500 rpm.

Unfortunately, the RX-7 was born with feeble brakes, including narrow rear drums incapable of slowing a baby carriage. Here I attacked with vigor reminiscent of my uncle William Tecumseh’s Civil War sweep through Georgia. The only factory parts that survived my assault were the front calipers. I installed Mazda Cosmo discs in the rear, AP-Lockheed vented rotors in front, an adjustable balance bar to regulate effort distribution, twin Hurst Airheart master cylinders operated by a significantly stiffer brake pedal, and flexible hoses jacketed by braided stainless steel (to further diminish that annoying squishy-pedal feeling). Eliminating the vacuum booster raised effort appreciably, but my new system was linear acting and totally fade free.

Other chassis mods included clipping one coil from each spring to raise their rates while lowering the ride height, a new Quickor adjustable rear anti-roll bar, and installation of a trick Racing Beat strut tower cap that lowers the car’s nose without loss of wheel travel. The factory 13-inch wheels were replaced by 15-inch Hayashi Racing center-lock rims shod with BFG G-Force 195/55VR-15 radials. Moving the battery to the trunk helped shift the weight distribution to 50.7 percent front/49.3 percent rear.

To invigorate the exterior, I installed MazdaSpeed front and rear spoilers and a molded fiberglass front bumper that trimmed a few pounds off the nose. Exterior mirrors pirated from a Dodge Colt were more attractive to my eye than the factory originals.

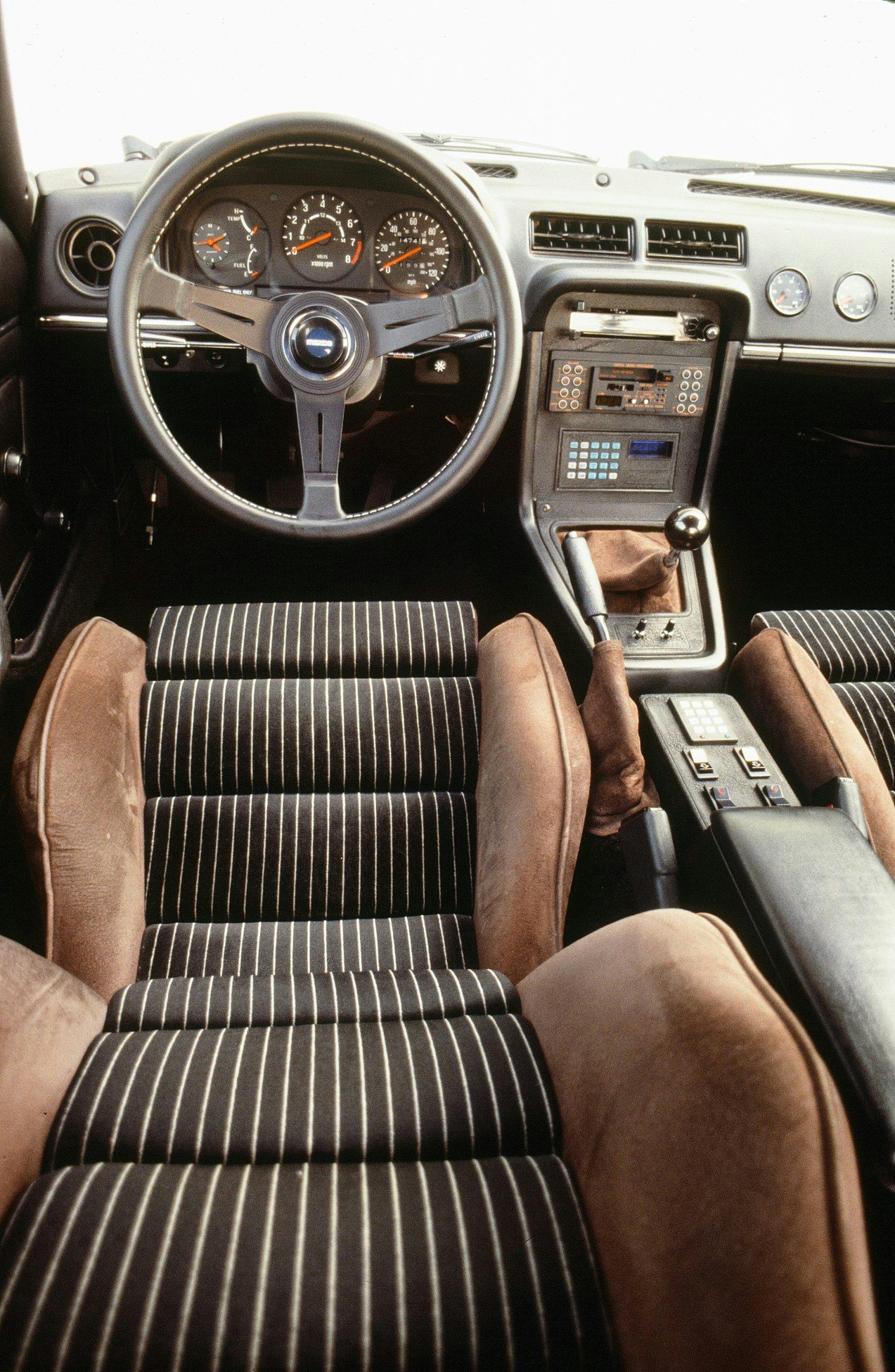

Thanks to my close friend George Venieris at Recaro USA, the interior makeover was creatively comprehensive. Heated and power-reclining Recaro buckets were swathed in pigskin hides and striped-velour center panels. VDO gauges reporting oil pressure and temperature were installed on the passenger side of the dash. A leather-wrapped Nardi steering wheel enhanced my nine and three handshake. The sound system was upgraded with a new Alpine control panel and subwoofers built into open space behind the seats. To complete the package, George concocted a pig-skinned case filled with Craftsman tools.

Over the years I swapped tires, upgraded the sound system, and kept tabs on my homemade brake hardware. The performance we measured way back when—0–60 in 7.9 seconds, 128 mph top speed, 0.85g on the skid pad—is modest by modern standards, but this car still sparkles in fun-to-drive. The tuned rotary has never missed a beat, and my trophy case has benefitted from this RX-7’s occasional car show attendance.

I do harbor two regrets: that the opportunity to share my rotary with Rudolf Uhlenhaut never materialized and that I’ve logged only 22,300 miles over four-plus decades. The good news is that today’s assignment is complete, local roads are dry, and it’s time to let Celine Dion sing.